A woman's industry? The role of women in the workforce of the

advertisement

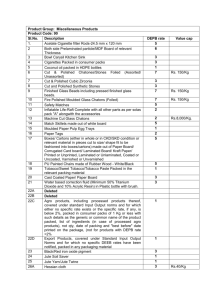

EHS Annual Conference 2010 ‘The Romance of Jute’ A Woman’s Industry? The role of women in the workforce of the Dundee jute industry c. 19451979 Dr Valerie Wright University of Dundee Introduction In the historiography, and popular memory, Dundee is portrayed as a ‘women’s town’. The roots of this characterisation can be found in the city’s population structure in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. In 1911 there was three women for every two men.1 In the same year women formed 43 percent of the labour force and 54.3 percent of women aged over 15 were in employment.2 The Jute Industry in Dundee is historically associated with high levels of female labour participation, with this being especially true in the pre 1945 period. Women’s role in jute in the first half of the twentieth century was significant for two related reasons. First, Dundee had a comparably high percentage of married working women throughout this period.3 In addition Dundee also had a comparatively high proportion of female headed households as a result of the disproportionate number of female ‘breadwinners’. Thus, Dundee’s description as a ‘women’s town’ can be traced to the dominant role that women played in the workforce of the jute industry and the economic and social consequences of this. Yet women’s role in the industry was reduced in the post-war period both as a result of jute’s decline in size and influence in the city and also as a result of increasing numbers of men replacing women as the industry became more capital intensive. This major structural change characterised the industry’s response to the contraction of markets for jute products both at home and in the export field. The changing labour market in Dundee was also extremely influential in the availability of women workers for the jute industry, with the industry experiencing a labour shortage in the immediate post-war years. The efficiency required by the jute industry to remain profitable was seriously undermined by such labour supply problems. This paper will contrast women’s role in the jute industry in the immediate post war years, when women were very much in demand, to the 1960s and 1970s when the industry had in some ways overcome its labour shortage and was no longer entirely dependent on the work of women. Arguably, Jute was no longer ‘a woman’s industry’ as it had been characterised in the first half of the twentieth century. However, the work of women in the jute industry was, and remains, significant in the description of Dundee as a ‘woman’s town’ in a historical context. This paper will consider whether or not this remained an accurate description of the city in the period under consideration, at least in an economic sense. Women and jute in the immediate post-war years 1 E. Gordon, Women and the Labour Movement in Scotland, 1850-1914, Clarendon, Oxford, 1991, p. 142. Ibid. 3 The percentage of married women in employment in Dundee was 23.4 in 1911, 24 in 1921, 33 in 1931 and 30.6 in 1951. The corresponding figures for Glasgow, which were also higher than the Scottish national average, and were the second highest after Dundee were, 5.5 in 1911, 6.1 in 1921, 7.3 in 1931 and 18.5. Census of Scotland, 1911-1951. 2 Following the Second World War the jute industry’s prevalence in the local labour market was under threat, which had profound implications for the role of women in the industry. Immediately following the war there was a high demand for jute products as the market returned to peacetime conditions. However the jute industry experienced a labour shortage and struggled to attract women back into the industry following their involvement in munitions industries. In 1945 Mr Alex J. Stewart, president of the Dundee Chamber of Commerce, estimated that the jute industry could absorb approximately 8,000 workers.4 This labour shortage persisted throughout the 1950s and was influential in the decisions made by management in the jute industry. In the immediate post-war years efforts were made to reclaim jute workers through the introduction of a registration system to track individuals who had previously worked in jute before the war. Attempts were also made to prevent such individuals working in other industries through the Control of Engagement Orders, which was reintroduced in 1947. Women jute workers were the focus of these efforts, and the industry employed increasing numbers of juveniles as well as European Voluntary Workers and Displaced Persons.5 As an article in The Scotsman argued ‘the labour position is causing some headaches to jute manufacturers who have for so long had so big a pool of women’s labour from which to draw’.6 Indeed in 1947 Jute Industries, one of the leading companies in the jute industry in Dundee, established a training scheme to ‘make the Jute Trade as attractive as possible to juveniles’, which involved the provision of lectures in rove spinning from specially trained instructors as well as ‘Industrial Courses’ at the technical college in Dundee.7 Two years later Jute Industries, held talks with other companies who wished to institute similar training due to the ‘increasing demand for Male Sliver Spinners owing to the starting up of new machinery throughout the Trade’ and the ‘need to attract young workers’.8 Boys were the targets of such schemes, with the provision of training providing the position of spinner with a qualification that made it a ‘credible’ or ‘respectable’ prospect. Men were not expected to return from war and replace women in the jute industry, as was the case in other industries, as jute remained ‘women’s work’ in the post-war years. Although Jute Industries provided training for ex-servicemen who wished to train as rove spinners.9 Nevertheless, women continued to be a comparatively low-cost labour force following the war, as were juveniles. Yet, in the immediate post-war years Jute Industries employed increasing numbers of men especially to extend night shift working and the double day shift. This practice had begun in the jute industry in the interwar years as protective legislation prevented women from working after 10pm at night or on a shift though the night.10 The displacement of female workers with men may also have been an attempt to increase labour productivity, especially given the labour shortage in the industry. In January 1946 the Association of Jute Spinners and Manufacturers (AJSM), which represented and organised jute companies in Dundee who chose to be affiliated, suggested that male rove spinners should be employed with three men working four frames.11 Women who agreed to the same ‘increased charge’ were paid an equal wage to their male 4 The Scotsman, 29 March 1945. The economic downturn and unemployment experienced in the interwar years in Dundee were to leave a lasting impression. In the late 1930s approximately 8,000 people left the jute industry, at a time when other traditional staple industries were benefiting from increased orders as a result of the government’s drive for rearmament. 5 C. Morelli and J. Tomlinson, ‘Women and Work after the Second World War: A Case Study of the Jute Industry, Circa 1945-1954’, Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2008, p. 64. Also see Jute Industries, General Committee Minute Book, Dundee University Archives, MS 66/10/1/4/5, 9 September 1948. 6 The Scotsman, 24 October 1947. 7 Jute Industries, General Committee Minute Book, 30 May 1946 and 9 September 1948. 8 Ibid, 27 January 1949. 9 Ibid, 9 May 1946. 10 The government later revised such legislation to allow women to work until 11pm in order that industries could fully implement double day shifts ‘to meet production needs’. Ministry of Labour and National Service, Report of Committee on Double Day Shift Working, National Archives, CAB/129/19, 1947. 11 Jute Industries, General Committee Minute Book, MS 66/10/1/4/4, 10 January 1946. counterparts, such was the need for rove spinners, although this was withdrawn two weeks later as the response from men was deemed ‘favourable’.12 Admittedly women were reluctant to increase their ‘charges’ and perform extra work as a strike at Jute Industries Walton Works in September 1947 illustrated.13 Jute Industries also extended night shift working with the explicit purpose of ‘absorbing male spinners’ and ‘building up’ the labour force for the introduction of a double day shift.14 Yet difficulty was encountered as the company struggled to fully staff such shifts and advertisements were placed in the local press for workers. 15 Jute Industries also introduced a double day shift comprised of ‘100% men’ in its Caldrum Works in 1947.16 Similarly Low & Bonar established a night shift ‘with purely male labour’ in the same year. 17 The need to recruit male workers was largely due to the fact that there remained reluctance on the part of Dundee women to return to the jute industry, even taking in to account the decline in female participation in the labour market following the war as a result of a rise in fertility rates. In Dundee the marriage and birth rates both increased in the immediate post-war years. It could be argued that women chose to remain at home to fulfil the roles of wife and mother rather than work in jute.18 In the post war economic boom, more married Dundonian women could have made this choice as male unemployment was lower. However women in Dundee worked because they had to and because they wanted to, as had been the case in the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. Many women would have continued to participate in the labour force in spite of discourses concerning ‘good motherhood’, domesticity and the respectability of being a non-working wife. They may have done so in order to afford luxuries such as consumer durables or to simply have a better standard of living. Indeed the participation of women in Dundee’s labour force continued to be comparably high. 19 In 1951 33,127 women were recorded as being in employment or 39.5 percent of the workforce, notably married women accounted for 30.6 percent. Married women were therefore an important source of labour in post-war Dundee. As a result Dundee City Council, in an attempt to facilitate the return to work of married women, continued public provision of nurseries in the post-war years. Interestingly these nurseries kept the same hours as the jute works.20 The council also subsidised workplace nurseries. This policy was in contrast to the patriarchal attitudes of local politicians who opposed married women working. Such individuals argued that the council should be concentrating on improving male employment prospects while women should be in the home caring for their children and homes. At a national level the Ministry of Health also did not support the council’s nursery building programme in the early 1950s, although the council continued to lobby for nursery expansion to enable married women to work. Jute companies became increasingly anxious as the labour shortage in the industry continued. Towards the end of the Second World War attempts had been made to attract women back to the industry while men were simultaneously being recruited in greater numbers. This did not involve the obvious increase in wages but instead included the improvement of working conditions. Jute companies continued to employ this strategy in the post-war years, which involved the establishment of ‘welfare facilities’ such as canteens, lockers, washing facilities, improved toilets and heating as well as the provision of drinking fountains and ‘forenoon tea’ for 12 Ibid, 28 February 1946. Ibid, MS 66/10/1/4/5, 18 September 1947. 14 Ibid, MS 66/10/1/4/4, 4 April 1946. 15 Ibid, MS 66/10/1/4/5, 6 May 1948. 16 Ibid, 20 February 1947. 17 The Times, 15 September 1947. 18 The Scotsman argued that ‘many of the younger women have not returned to Dundee or have married, and remained out of industry’. 24 October 1947. 19 In 1951 married women accounted for 18.5 percent of the workforce in Glasgow, 17.6 percent in Edinburgh and 12.5 percent in Aberdeen. The Scottish national rate was 14.8 percent. 20 Morelli and Tomlinson, ‘Women and Work after the Second World War’, p. 69-70. 13 workers.21 Several companies also opened their own nurseries. Low & Bonar, a leading jute company, were the first to do so in 1947 with Jute Industries following suit a year later, with a second following in 1950.22 Jute Industries gave three reasons for the establishment of nurseries, the recruitment and retention of working mothers, to prevent absenteeism among working mothers, and the fact that public provision was full and had long waiting lists.23 The nurseries ensured some measure of success for Jute Industries. In August 1948 13 workers had taken advantage of the facilities, this included 6 full time workers, 2 part-time workers and 5 workers who intended to return to work. It was also expected that 10 evening shift workers would change over to full time work.24 A month later it was reported that the opening of the day nursery had resulted in ‘835 hours of additional work being obtained’.25 Indeed Jute Industries felt that the provision of day nurseries would be ‘the main factor likely to help recruitment of women workers, particularly the type of productive workers likely to be in demand and in short supply’. 26 However jute was not the only industry in which female labour was required. In the immediate post war years Dundee was given ‘Development Area’ status by the government under the Distribution of Industry Act of 1945. Dundee City Council also responded to pessimism concerning the future of the jute industry by pro-actively launching initiatives to attract new industries to the city. As officials of the Dundee Chamber of Commerce argued ‘too many eggs should not be placed in the jute basket’.27 The Board of Trade was supportive of this policy, which prominently positioned Dundee’s female labour force as a selling point to industries locating in the area. An official stated in 1946 that ‘they were out to see that no woman in the district would be out of work’.28 The City Council and Board of Trade were successful and inevitably women in Dundee chose to work in many of the new industries attracted. Before the Second World War there had bee little choice in terms of employment for women, with the jute industry being dominant. Jute accounted for a third of the total insured population of Dundee, with the comparable rate in November 1948 being 14,000 of 66,000 insured workers.29 The experience of high unemployment in the interwar years accompanied by the relatively low wages paid in jute ensured that when other, often better paid, options became available women seized them.30 Women therefore became ‘more selective’ in the post-war years, with the ‘lighter industries’ offering ‘novelty and better pay’.31 Thus as the Chair of the Scottish Women’s TUC stated in 1949 ‘lassies in Dundee would not in future find it absolutely necessary to go into jute factories’.32 21 Jute Industries, General Committee Minute Book, MS 66/10/1/4/4, 27 February 1942, 19 November 1943, 15 September 1944, 1 December 1944, 14 September 1945, and 3 January 1946. 22 The first nursery at Camperdown Works accommodated 16 babies under 1 year, 12 tweenies aged 1 to 2 years, and 37 toddlers aged 2 to 5 years. Staff employed included a matron, deputy matron, 3 staff nurses, 8 nursery helps, a cook and two part time cleaners. A yearly expenditure of £4225 was anticipated. Employees were charged between 4/- and 7/6d per week. Jute Industries, General Committee Minute Book, MS 66/10/1/4/5, 27 November 1947, 8 January 1948, 5 February 1948, 1 July 1948, 19 May 1949. The second nursery at Manhattan Works cost approximately £7,200. 29 September 1949. 23 Ibid, 1 July 1948. 24 Ibid, 5 August 1948 25 Ibid, 16 September 1948 26 Ibid, MS 66/10/1/4/5, 19 May 1949. 27 The Scotsman, 29 March 1945. 28 Morelli and Tomlinson, ‘Women and Work after the Second World War’, p. 68. 29 The Scotsman, 6 November 1948. 30 In 1947 1,600 men and 1,344 women were employed in new industries recently located in Dundee, by 1949 the total was 4,000. Morelli and Tomlinson, ‘Women and Work after the Second World War’, p. 76. Mr McHugh of Dundee Corporation argued that this was a record ‘which could not be equalled anywhere else in Britain’ with Dundee ‘bidding fair’ to become ‘the Birmingham of Scotland’. The Scotsman, 25 September 1947. 31 The Scotsman, 24 October 1947. 32 Morelli and Tomlinson, ‘Women and Work after the Second World War’, p. 79. Yet within the business community it was felt that Dundee had been ‘rather ‘oversold’ from the point of view of labour’ and that there would have been ‘less upheaval’ if the new industries had been introduced more gradually in to the city.33 Unsurprisingly this concern continued unabated in the face of the labour shortage. A report from a ‘special correspondent’ in The Scotsman suggested that there were ‘plenty of people in the business in Dundee’ who had argued that ‘even more pressing’ than the need to protect jute from competition in India was the need to attain ‘an assurance of protection against industries which are being introduced to the city as a matter of government policy’.34 It was felt that such industries were being ‘subsidised from the public purse’ and were ‘denuding the jute mills of much wanted labour’. Recruitment to the jute industry which it was estimated required a further ‘six or seven thousand workers’ was proving ‘very difficult’ because of ‘full-blooded propaganda about ‘dark satanic mills’’. Thus it was argued that the ‘psychological disturbance’ of the new industries was ‘great’. These fears were intensified during 1948 when the raw jute supply to Dundee was cut and employers were forced to make 800 people redundant with further workers being placed on short time. Tom Cook MP argued that the ‘jute industry was vital not only for Dundee, but for the country itself’ with it being ‘necessary to keep it fully alive and at peak production’.35 The main concern was that ‘once people left and got other jobs they were lost to this vital industry’. By 1950 the directors of the Dundee Chamber of Commerce supported the jute industry in its request to the President of the Board of Trade that ‘from the labour point of view, no further new industries should be located in Dundee at present’.36 Mr W.N.G. Walker of Jute Industries suggested that the introduction of new industries to Dundee had prevented ‘the rehabilitation of the jute industry after its drastic war-time concentration’ and were ‘on a scale out of all proportion to the labour available’.37 Walker also suggested that ‘the serious and ever-increasing shortage of labour’ in the jute industry hindered the expansion of production for sale in home and dollar markets in spite of attempts at capital investment to improve the productivity of the industry. He hoped that government sponsored bodies and official would ‘take action before the situation deteriorates further’. Walker’s statements proved prophetic with a special meeting being held of the Dundee and District Local Employment Committee in April 1950, at which representatives from the Board of Trade in Scotland, the Board of Trade and the Ministry of Labour were all present. The necessity of a ‘master plan’ for Dundee’s future was considered, with considerations including the ‘up-grading of labour by training’, the provision of additional opportunities for part-time work as well as improving transport facilities.38 At this meeting it was found that although jute was ‘no longer the dominant source of employment in the city’ with nearly ‘one in five’ of the working population being occupied in jute it was ‘still the main factor’ in the city’s prosperity. It followed therefore that ‘any future assessment of labour requirements in Dundee must be greatly affected by the needs of the jute industry’. Consequently the Board of Trade ruled that no further new industrial developments will be allowed to take place in Dundee.39 Even taking these recommendations into account the government departments concerned felt that there would still be a shortage of labour in Dundee which could ‘only be overcome by the importation of 33 The Scotsman, 24 October 1947. Ibid, 12 June 1948. 35 Ibid, 22 November 1948. 36 Ibid, 14 March 1950. 37 Ibid, 21 March 1950. 38 Ibid, 19 April 1950. The absence of part-time work in the jute industry was surprising given the rise in such work among women in the post war years at a national level. In contrast the Lancashire cotton industry, which was also keen to attract more women, offered part-time work and was therefore more flexible in terms of taking into account the ‘double burden’ of women’s work in the home and workplace. 39 Although it was decided that ‘reasonable and economic expansion of existing new or old industries (including jute) will be approved, especially if such expansions are expected to contribute to increasing exports or saving dollar imports’. Ibid. 34 additional workers’ although it was ‘not easy to see where the additional population is likely to come from’.40 ‘It wis a mans job’ – capital investment and the recruitment of men in the jute industry In spite of the influx of new industries in the late 1940s, and the fears expressed by jute employers, the jute industry remained Dundee’s largest employer until 1966. The industry experienced full employment during the 1950s, and although the labour shortage persisted throughout this decade, in the 1960s it would appear that the jute industry ceased its efforts to attract women workers. Perhaps as a result of its limited success in this regard, company nurseries were closed and no further improvements were made in working conditions in terms of ‘welfare facilities’. It is possible that the jute industry had accepted the fact that women were not returning, as there were more attractive employment options in the city, and instead focused on lowering its reliance on labour and the recruitment of men. As Figure 1 illustrates (see Appendix 1) the percentage of women working in the jute industry declined steadily in the post-war years relative to the percentage of men. Between the years 1948 and 1977 male employment in jute fell by 33 percent, while in the same period female employment was reduced by 78 percent.41 This translates to a reduction in the ratio of female employees to male from 1.6:1 in 1948 to 0.5:1 in 1977, which was fairly dramatic, especially given the jute industry’s historic connection with women workers.42 In the post-war years, and the 1950s especially, the leading jute companies made attempts to combat the labour shortage in the industry through capital expenditure on more efficient machinery in order to lower labour requirements. Some companies, including Jute Industries and Low & Bonar had begun this process in the interwar years. Such modernisation and capital investment in machinery had also been among the suggestions outlined in the 1948 Jute working Party Report for raising efficiency in the industry. As the retiring president of the AJSM, Mr J. Raymond Scott, argued in 1950 there seemed no prospect of increasing the present labour force but there was ‘every reason to hope for greater production with existing labour’. 43 In the postwar years many innovations were made, first in spinning and then in weaving. In spinning automatic followed by high-speed sliver spindles were introduced, while in weaving individual electric motors, circular looms for bag making, wide looms and automatic cop loading were all introduced.44 In both processes plant and equipment were modernised. Jute Industries were one of the first companies to invest in a policy of ‘progressive modernisation’ in the post-war years in spinning which included the installation of sliver spinning machinery with ‘considerable progress’ being made with regard to the development of automatic weaving.45 Mechanical developments were slower in automatic weaving as the quality and preparation of the yarn had to be of the highest possible standard and this required experimentation. By September 1950 it was estimated that 73 percent of the spindles in the jute industry were high speed or sliver, which compared favourably with the 1939 figure of 39 percent.46 However Howe argues that by the early 1960s the industry had ‘certainly passed the peak of its new capital expansion rate’.47 In 40 Sir Garnett Wilson provided evidence for the number of workers leaving jute for new industries, stating that one ‘new’ firm had 397 employees, of whom 15 men and 52 women had left the jute industry. Ibid. 41 W. Stewart Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, 1960-1977, Decline and Diversification, AUP, 1982, p. 123. 42 Ibid. 43 The Scotsman, 17 March 1950. 44 A Times correspondent argued that the introduction of automatic and circular weaving was ‘the first important developments of the loom for a century in this industry’. The Times, 25 April 1952. 45 Jute Industries argued that this enabled the company to be ‘one of the cheapest producers in the industry’ as well as permitting ‘higher wages’, better working conditions, and a better quality of yarn. The Scotsman, 15 March 1949 and The Times, 30 March 1949. 46 The Scotsman, 17 March 1949. 47 Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, p. 139. addition while Jute Industries, Low & Bonar and other industry leaders modernised in this manner such innovations were not adopted equally across the industry. 48 This strategy of capital investment was dependent on the further extension of double shift working in order to ‘write off the new plant over as large an output as possible’, yet as the shortage of labour persisted this strategy could not be wholly successful. 49 Indeed some companies were forced to acquire other businesses to gain more labour as opposed to installing more machinery in their own plants.50 At least two of the industry leaders, Jute Industries and Low and Bonar suggested that the labour shortage was to blame for their inability to meet the demands of their customers. As early as 1946 Mr Ernest Cox, chairman of Jute Industries, suggested that the labour shortage had ‘forced many of our customers to use Calcutta made goods’.51 He hoped that when the labour shortage was ‘overcome’ the company would ‘regain the ground we have lost temporarily’. The persistence of the labour shortage ensured that this was not the case. Therefore in the early 1950s Jute Industries relied on the ‘expansion of mass production lines, coupled with modernisation’ which it found ‘could increase materially the productivity of the industry without a very large increase in the labour force’.52 A ‘special report’ on the jute industry published in The Times in April 1952 supports this statement and suggests that output in the industry had gradually increased per worker over the period 1930-1951, with post-war figures giving ‘a general indication of increasing productivity’. 53 In 1952 Mr W.G.N. Walker, chairman of Jute Industries, suggested that his company’s productivity per worker per hour had increased by ‘no less than 33 percent’ in the last five years as a result of the introduction of ‘modern labour-saving machinery and redeployment’.54 The move of Jute Industries and Low & Bonar into polypropylene production in the early 1960s was another way in which the labour shortage was in some ways overcome. Polypropylene was more capital intensive than jute, therefore production per operative was higher and both companies were able to reduce their dependence upon labour. As the jute industry became increasingly capital intensive, this further intensified the decline in the numbers of women employed in the industry. Between 1960 and 1977 the number of women working in the industry fell by 68 percent, the equivalent figure for men was 40 percent, which resulted in men accounting for two-thirds of the workforce.55 Margaret Fenwick, former general secretary of the Dundee Union of Jute, Flax and Kindred Textile Workers (DUJFW), the main union for textile workers in Dundee, also stated that women left the jute industry as the machinery became ‘more difficult for the women to handle’ and the ‘machine charges got greater’.56 She suggested that as the companies made attempts to increase labour productivity in weaving, the number of looms each woman had to operate increased, and while automation was introduced to make the job easier, ‘it never ever really wis successful’. Bella Keizer, a former weaver, was fairly annoyed by the fact that while the jute trade ‘wis heavy physical manual work’ which ‘took yer bloody guts out’ women were employed and ‘when they automised the bloody looms they put men in’.57 In addition as wider looms were introduced to 48 It was also suggested that the failure of some companies to modernise exacerbated the loss of female workers in such establishments to new industries. The Scotsman, 24 October 1947. 49 Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, p. 124. Yet Jute Industries had more success in expanding shift working with its spinning mills operating ‘round the clock’ on three shifts by 1963. The Times, 21 January 1963. 50 Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, p. 124. 51 The Times, 7 February 1946. 52 Ibid, 19 March 1951. 53 Ibid, 25 April 1952. 54 Ibid, 11 March 1952. The equivalent figure for 1951-1956 was an increase in productivity per worker of 27 percent which Walker again attributed to the installation of modern machinery. The Times, 12 March 1956. 55 Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, p. 145. 56 Dundee Oral History Project (DOHP), Transcript 044/A/1, Dundee Local Studies Library, interview dated 1985. 57 Ibid, Transcript 022/C/2. produce the wide cloth required for carpet backing Fenwick argued that the stretching involved for women resulted in ‘miscarriages .. cervical cancer, this sort o’ thing’. Thus ‘women werenae able tae cope, ye know, so more and more men were trained intae the industry’. As she stated ‘the heavier the machine wis eh it wisnae a womans job anymore, ye know, … It wis a mans job’. In 1961 these issues were considered by the AJSM as a result of comments made by Mrs Fenwick. She had suggested that 5 yard loom weaving and above should be ‘a male responsibility’ as it was ‘outwith the capabilities of a woman’.58 It was also suggested that women should not work on batching or in the movement of full drawing frame cans over long distances. In response the AJSM stated that the suggested change over from female to male labour would ‘cause a complete upheaval in wide loom development’ as male labour was not available in the required numbers. In addition as the industry was not expanding, a large number of women would be made redundant as a result of this proposed change. Surprisingly union officials were ‘prepared to accept the redundancy of women if men were used for the wide looms’ and were not interested in ‘male rates for female operatives on 5 yard looms’ or in batching or drawing occupations. The AJSM, stated that it could not accept ‘an arbitrary statement’ that 5 yard looms and over were ‘too heavy’ for female operatives. Mr Reid, of AIC Ltd, a firm of industrial consultants hired by the AJSM on behalf of the industry, stated that there was a ‘top limit’ of physical effort applicable to women and irrespective of the amount of compensating relaxation allowance they could not handle in excess of that limit’. In this sense the points put forward by the Union were considered ‘valid’ and ‘certain occupations’ would require individual consideration. Thus Reid suggested that medical advice should be sought on ‘the stretching question’. The outcome of these discussions is not clear from the archives, however it is interesting that the industry, as represented by the AJSM, was opposed to changing wide loom weaving to ‘a man’s job’ while the Union demanded this, even at the cost of female redundancy. It was perhaps the case that female workers themselves felt that these jobs were ‘outwith their capacity’ but it is doubtful that they would have been in favour of redundancy. Notably the DUJFW refused to even consider accepting male wages for women engaged in wide loom weaving, it simply wanted the job designated as ‘male’. Therefore, in this case, the union may have contributed to the declining numbers of women employed in the jute industry. Arguably as the machinery installed became more sophisticated and demanding, some jobs in the jute industry were designated as requiring greater skill and men were employed. The extension of the double shift system throughout the industry was also instrumental in the expansion of men’s employment in jute, as was the hiring of men to work night shifts perceived to be unsuitable for married mothers. The differential in wage rates between male nightshift workers and the female day shift was attributed to the fact that men on average operated more machinery and were therefore seen as more productive. As Fenwick stated in relation to male weavers ‘it wis amazing once they did get used tae it they made damn good weavers, they made good weavers, Eh, Eh must say that’. Whether such marginalisation of women was a purely economic concern relating to the relative productivity of men and women is open for debate, and may simultaneously have been a product of patriarchal attitudes relating to measurements of skill. Indeed the majority of organised training offered to jute workers in the post-war years was aimed at the male occupation of tenter, a type of mechanic who oversaw the operation of the machinery, which was seen as a ‘skilled’ occupation.59 Such classes were held at the technical college in Dundee with apprenticeship schemes of three years being essential. This training undoubtedly elevated the status of this occupation within the industry. Yet there were some gains to be made by women remaining in the jute industry as male employment increased in the 1960s and 1970s. As figure 2 (see Appendix 1) illustrates, overall the gap between male and female hourly earnings, as measured by the ratio of male to female AJSM, Minutes of Joint Meetings with workers’ representatives, 11 May 1961. Ibid, 4 March 1952, 28 April 1952, 25 August 1952, 8 December 1952, 22 December 1952, 30 January 1952, 23 April 1953, 14 April 1954, 21 February 1955, 5 May 1955, 27 February 1956, 13 May 1959. 58 59 wages, declined between 1960 and 1977 from 1.47 to 1.13, although there were substantial fluctuations during this period. Women in the industry therefore ‘significantly improved their earning position’ and this did not ‘appear to have been as a result of overtime working’. 60 However a gap did remain in earnings in spite of the Equal Pay Act of 1970. While men worked a longer working week as illustrated in figure 3 (see Appendix 1) this does not account for the difference in hourly rates. Thus patriarchal attitudes remained in the jute industry, as well as many others in the 1970s. Indeed an article discussing the implications of the forthcoming Equal Pay Act published in November 1969 in JIL News, the works newspaper of Jute Industries, was entitled ‘Money That’s Strictly for the Birds’. The article outlined that the act would mean higher wages for women, changes in the terms of employment, the use of job evaluation and ‘probably higher prices’ throughout the industry.61 It also suggested that the act would also result in ‘changes in the home which will not be noticeable quickly but will have a great affect on us all’. This was a strange attitude for a company who employed married women, although as the numbers of men in the industry increased and its reliance on women’s work declined, Jute Industries was perhaps more able to make such comments. Conclusion The high participation of women in the jute industry in Dundee in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was undoubtedly influential in the city’s characterisation as a ‘women’s town’. This is a description which lives on in contemporary Dundee and one of which Dundonians are proud. This in itself is not to be criticised. However in the post-war years Dundee’s jute industry could no longer be described as ‘a women’s industry’ and this perhaps has implications for the way in which Dundee has continued to be characterised as a women’s town by virtue of the historical legacy of women’s prominent role in jute. The role that women played in the jute industry in the early part of the twentieth century was diminished in the post-war period. This was largely as a result of the labour shortage experienced in the industry. Women were reluctant to return to the jute industry following the Second World War following the experience of high unemployment during the interwar years as a result of market fluctuations and the cyclical nature of the jute industry. The experience of munitions work during the War was also influential for Dundonian women. Dundee’s status as a Development Area in the post-war years ensured that there were many new industries locating in the city which also required women’s work and former preparers, spinners and weavers voted with their feet and took up employment in these industries, many of which utilised similar skills to the production line engineering required in munitions work. The response of jute employers in the immediate post-war years was to try and persuade women to come back to jute by providing ‘welfare facilities’ to improve the conditions of work, this included the establishment of nurseries to persuade married women to return to jute. It was hoped that in this way jute would be equally as attractive as the new industries locating in the city. However there was one small problem, the wages were higher in these new industries. By the 1960s jute employers had ceased such efforts to attract women and instead had began focusing on the recruitment of men and more importantly, lowering their overall reliance on labour. The practice of employing men in greater numbers to replace female workers had began in the interwar years in order to establish night shifts and extend the use of double day shifts as women were unable to work night shift or beyond 10pm at night as a result of protective legislation. In the post-war years men were recruited as shift working was further extended. The simple explanation for greater shift working was the need to run machinery for longer hours. In the post-war years most jute companies, and especially the industry leaders Jute Industries and 60 61 Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, p. 128-129. JIL News, ‘ Money That’s Strictly for the Birds’, MS 66/10/15/1/1, November 1969. Low & Bonar, embarked upon a programme of intensive capital investment. This involved the installation of new and more modern spinning and weaving machinery which crucially required fewer workers to operate. However in order to justify the expenditure and increase productivity levels, such new machinery had to run for longer hours. As a result of such strategy to improve the industry’s efficiency, productivity levels were generally increased while the number of employees was reduced. Thus the industry was successful in lowering its reliance on labour and especially women’s work. Men were increasingly more likely to work night shifts and double day shifts, which women themselves were more reluctant to work due to family commitments. The DJFWU also argued that the new machinery installed in the industry was also ‘outwith the capabilities of women’. The diminishing role of women in the jute industry in the post-war years is clear, especially in the 1960s and 1970s when the ratio of women to men fell from 1.6:1 in 1948 to 0.5:1 in 1977. Arguably jute’s role in the history of Dundee as a ‘women’s town’ was at an end. Yet women’s work continued to be in demand in many of the new industries locating in Dundee in the post-war years. However the ‘skilled’ positions offered by such employers as Timex and the National Cash Register, prominent companies locating in post-war Dundee, were men’s jobs. Men occupied the comparatively higher paid management and supervisory roles as well as the specialist mechanic roles. Women remained an ‘unskilled’ workforce as they had largely been in jute. Thus whether women were really ever ‘in charge’ in Dundee as the image of the ‘women’s town’ suggests is open for debate, even taking into account the complexity of this description of the city. This is especially true of the post-war years given the reliance of this characterisation on the role of women in the jute industry. Appendix 1 Figure 1 Figure 2 – Male and Female Hourly Earnings Ratio – Jute Industry – Men/Women 1960 1.47 1961 1.44 1962 1.40 1963 1.45 1964 1.41 1965 1.43 1966 1.44 1967 1.48 1968 1.45 1969 1.45 1970 1.61 1971 1.37 1972 1.40 1973 1.33 1974 1.26 1975 1.23 1976 1.12 1977 1.13 Source: W. Stewart Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, 1960-1977, Decline and Diversification, AUP, 1982, p. 128. Figure 3 – Earnings and Hours Worked in the Jute Industry Men aged 21 and Women aged 18 over and over Average weekly Average weekly Average weekly Average weekly earnings hours worked earnings hours worked 1960 11.79 47.8 7.37 42.4 1961 11.93 45.6 7.54 40.8 1962 12.88 46.4 8.05 40.7 1963 13.43 46.0 8.13 40.5 1964 14.57 46.3 8.85 39.5 1965 15.71 47.0 9.21 39.6 1966 16.56 46.3 9.62 38.4 1967 18.08 45.6 10.36 38.3 1968 18.96 45.5 10.80 37.8 1969 21.47 45.2 12.32 37.7 1970 23.25 44.1 12.52 37.6 1971 25.02 44.9 15.70 38.0 1972 29.40 44.2 18.37 38.1 1973 33.14 43.3 21.72 37.5 1974 40.45 43.5 28.51 38.6 1975 50.50 42.8 34.74 36.1 1976 54.44 43.0 42.48 37.5 1977 56.36 42.7 42.47 36.3 Source: W. Stewart Howe, The Dundee Textiles Industry, 1960-1977, Decline and Diversification, AUP, 1982, p. 151.

![Booking Form SPaRC ASM 27 March 2014[1].ppt](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005467834_1-e4871078a04d228fe869fa8fba421428-300x300.png)