Admin-ProceduralFairness

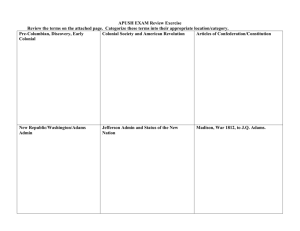

advertisement

What is Administrative Law? Public law deals with the relationship between the individual and the state Both public law and constitutional law deal with how the government may exercise its powers Administrative law governs the relationship between the executive and citizens (i.e. governs the administration) and is designed to protect citizens from abuse of power. State and civil society are implicated in admin law. Law applies to everyone, including government. Constitution, including division of power, is a starting point for assessing legitimacy of state action. There is overlap between three branches of government: In legislative it is prospective (future oriented), public interest minded. Judicial is retrospective, localized in outcome and narrow in application. Executive or admin decision making has some characteristics of both. Executive branch replicates dualism created by division of powers. Admin law defines boundaries of government action. Early admin law defined the boundaries of functioning of public agencies e.g. railways and represented switch to expertise rather than political patronage. Later initiatives in heath, welfare and immigration. In 1950 welfare state came to full bloom. Later encompassed environmental issues and anti-discrimination issues. In the nineties decentralization and de-nationalization was the main trend. Responsible government – government is collectively responsible, but ministers account to Parliament for activities of their departments. Benefits of decision making by bodies independent from government include: Prevents the government from interfering e.g. settlement of labor disputes. Expertise is accumulated and carried through government changes e.g. environmental review tribunal. Rights are determined in consistent manner e.g. Immigration Tribunal. To unsure objectivity in decisions on entitlement to government benefits. When the matters are to politicized and government lost credibility. Benefits of administrative decision making over judicial decision making: Nature of decisions inappropriate for courts, governmental rather than judicial. Specialized experience and expertise may be needed. Claim involve small sums of many and are not economically viable for litigation. More informal process and no need for legal representation may expedite the decisions. Government can influence decision makers in ABCs by cutting off resources, amending guidelines and statutes (ABCs = agencies, boards and commissions, terms are not applied in consistent way, to find the form and structure look into funding statute). Executive power is delegated to non-government agencies. They can only delegate powers that they posses. The decisions are subject to court review if there is bad faith or abuse of power. Subject matter of admin law: Employment Regulated industries e.g. utilities, railways Economic activities e.g. mergers and takeovers. Profession and trades Social control Human rights Income support Public services Institutions of admin law: Legislatures – nearly all public programs originate with a statute. Cabinet and ministers – may be empowered to supplement the statutes by delegated legislation and/or may exercise discretionary powers that directly affect individuals. Some statutes provide for right to appeal to the Cabinet from decisions of independent agencies. Also influences ABCs by controlling funds. Municipalities – some of the programs with most impact on individuals are administered by municipalities. Members of councils and trustees are usually elected. Crown corporations – provide important public services and enjoy a great deal of independence, but are influenced by government by funding and appointment to BoD. Hybrids between public and private law. Private bodies with public functions – e.g. sports associations, real estate boards, Ontario CASs, universities, Independent administrative agencies: 1. Similarities: 1. Measure of independence from government, can’t be directed by the minister and minister is not responsible for them. 2. Those who are affected by their decisions are given an opportunity to participate in decision making. 3. Operate close to “sharp end” where the public program is applied to an individual. 4. Specialized. 2. Differences: 1. Decisions fall on the spectrum between quasi judicial and policy making (political) 2. Structure is different in how much it resembles court. 3. Case load sizes vary 4. Places in overall decision making process vary form making recommendations to making final decisions. 5. Effect on individuals vary (imprisonment to deck building permit) 6. Compositions of membership vary. Political and administrative redress of individual grievances: Legislative - usually does not include resolving individual complaints, unless in exceptional cases of media involvement. Ombudsperson process in most provinces (p. 21) Internal mechanisms of admin agencies – often admin tribunals. Courts and administrative agencies (last resort): 3. Original jurisdiction, 4. Appeals – creation of statute, no inherent jurisdiction 5. Courts’ inherent judicial review jurisdiction (even in the absence of statutory right of appeal) superior courts inherited their supervisory jurisdiction from English royal courts. The remedies available were prerogative writs, which were used until 20 th century in Canada: 1. Certiorari – quash government decision 2. Prohibition – prohibit government from doing something 3. Mandamus – requirement to do something 4. Habeas corpus – relates to the legality of detention 6. Now the principles of judicial review emerged and they define when the courts can intervene in the administrative process when legislature provides no right of appeal: 1. Procedural impropriety deal with requirement of procedural fairness (prior notice, reasonable opportunity to respond, impartiality etc). 2. Illegality – administrative action has to be authorized by law. 3. Unreasonableness 4. Unconstitutionality. Judicial review is sought (with few exceptions) in the absence of an applicable appeal procedure. Two basic grounds are: Jurisdiction – the body that made the decisions did not have the power to make it. Fairness – problems (unfairness) with the process of decision making. Separation of powers, admin state and rule of Law. The rule of the law and the administrative state. Rule of law is a broad concept similar to liberty, democracy – basic, but not too clearly defined. It has following elements: 1. All legitimate exercises of public power have source in law, 2. all government agencies, officials and actors are subject to law and supervised by the courts 3. no one should be made to suffer except for a distinct breach of the law. The debate about the appropriate scope of governmental powers is on going as too much power can lead to biased decisions and not enough accountability for the decisions. Dicey names the following implications of the rule of the law: No separate body of public law, administered outside of “ordinary courts”, applicable to relations between government (admin powers) and individuals. It has following implications: o Courts have difficulties dealing with interests of administrative nature e.g. licenses, that fall outside of the scope of traditional common law interests like liberty of the person, property to freedom to contract. o Court deal with appeals of admin decisions as they would with hearing on appeal from a lower court. Functionalists (John Wills) criticized Dicey’s approach by: Challenging its historical accuracy by pointing out the limitations in “rule of the law” dogma like Crown’s immunity to tort liability at common law, or existence of local and specialized agencies in England that heard the disputes arising form regulatory legislation. Dicey’s disapproval of brad admin powers and preference for involvement of “ordinary courts” resolving disputes thwarted the efficiency of state functioning and was designed to “put public administration into straightjacket”. Focus of litigation on parties will relegate the “public aspect” of the dispute to secondary importance. Dicey has failed to appreciate that law is inevitably intertwined with policy and so it is not possible to determine the meaning of legislative provisions without considering policy implications. Therefore specialist agencies should make these determinations. Law has a facilitative and legitimizing aspect of law. State should be regarded as a source of good. Courts have limited competence on deciding issues of public policies and administration. Purely legalistic expertise is not that useful in admin law. Mullan on p. 31 tries to reconcile both views: Functionalists do not pay sufficient attention to democratic accountability and fundamental rights which can be realized in judicial process. No necessary inconsistency between values of rule of the law and efficient delivery of public programs and policies. A compromise is possible: o Admin law can – through statutory reform and judicial review – ensure procedural fairness and enhance accountability by encouraging public participation of parties not directly affected by the contemplated admin action. . Requirements to disclose all relevant information ensure that public interest groups receive funding and to provide reasons for decisions may be imposed on admin bodies. o Reviewing courts should show measure of deference to admin decisions but still scrutinize decisions contrary to the interests of intended statutory beneficiaries. o Specialized agencies are more competent in ascertain the intentions of the legislators, but sometimes an independent agent is useful (as implied by separation of powers) in preventing the subversion of clear meaning of the statute due to decision maker’s need to be reappointed or due to his tunnel vision. o Admin action should not violate Charter rights and admin bodies should be alert to this reality. At the same time courts must keep in mind that Charter gives them no mandate “to roll back the statutory protections of the welfare and regulatory state”. Admin bodies may be better equipped to weight infringements of Charter rights against competing public interests. Responsible government: Government is collectively responsible; ministers must individually account to parliament for the decisions and actions of his/her department. However large number of unelected public officials who are accountable within their delegated authority. Principled decision-making - public bodies are independent from government but carry on work for the gov’t. Fairness If economic basis, want decision to be made on a longer period of time rather within Independent voice when the government seems to have lost credibility - e.g. commission or enquiry (Walkerton, Arar) To figure the structure form of body, need to look at its founding statutes Boards and Commissions have discretion, but can be heavily influenced by government: Power of appointment, terms of office - seen to influence decision making Resources can be cut off. Example law commission of Canada Amend guidelines and policies of the board/commission. Crown Corporations Also governed by admin law Commercial aspect to government services that requires decision apart from political system. Requires greater flexibility Public, commercial aspect or purpose Examples: Bank of Canada - macro economic reg of currency; Canada post; Via Rail Municipalities Roads, sewers, transit parks Have policy function through enactment of by-laws Elected but independent from prov - still creates of statute - can be created and destroyed at government whim PROCEDURAL FAIRNESS BAKER 5 FACTORS Factors affecting content of procedural fairness (which is specific to each case): o Nature of the Decision and Procedure for Making the Decision The more process provided (the closer to the judicial end of the spectrum) – the more procedural fairness afforded o Nature of the Statutory Scheme Greater procedural fairness required where no appeal procedure – More determinative the decision o Importance of the decision to the Individual affected High standard of procedural fairness where important decision o Legitimate Expectations If legitimate expectations for a certain procedure – then procedural fairness requires the procedure But No Substantive Rights o Choices of Procedure made by the Agency itself Agency has discretion and expertise to choose procedure Scope: Decisions made by Cabinet Canada (Attorney General) v. Inuit Tapirisat of Canada [1980, SCR] - no duty of fairness for legislative functions Homex Realty and Development Co. Ltd. V. Wyoming (Village) [1980] SCR Canadian Association of Regulated Importers v. Canada (AG) [1994, Federal CA] - natural justice not applicable to policy decisions. Decisions affecting rights, privileges and interests Re Webb and Ontario Housing Corp (1978, ONCA) – Holder of right v. applicants Hutfield v. Board of Fort Sask. General Hospital District No. 98 (1986, Alta. QB)privileges attract procedural fairness, Legitimate expectations CUPE and Service Employees International Union v. Ontario (Minister of Labour) [2003, SCR] – no substantive legitimate expectations, decision maker=government. Reference re Canada Assistance Plan CAP [1991 SCR Mount Sinai Hospital v. Québec (Minister of Health and Social Services) [2001 SCR] SPPA In Ontario we have the Statutory Powers Procedures Act (SPPA), 1990 o Addresses threshold and content issues o Key provision is s. 3(1); this describes the application of the Act. o Look also at definitions in s. 1(1) Pre hearing------------ notice, discovery, disclosure Hearing -------------------- oral, written, evidence, examination. Cross, entitlement to counsel Post hearing ------------------------ Reasons Bias and lack of independence ---- second branch of NJ Pecuniary bias Energy Probe v. Canada (Atomic energy Control Board ) - Pecuniary and other material interests Prior active involvement with the matter 2747-3174 Quebec Inc v. Quebec (Regie des permis d’alcool), SCC 1996 – statutory authorization of bias……………………The determination of institutional bias presupposes that a well-informed person viewing the matter realistically and practically and having thought the matter through would have a reasonable apprehension of bias in a substantial number of cases Great Atlantic & Pacific Co. Of Canada v. Ontario (HRC) (1993) Ont. Div. Ct. – attitudinal bias, issue of appointment of HR activists to adjudicate complaints. Independence in the individual sense: is the adjudicative freedom that the d-m feel in exercising statutory responsibility due to 3 things: o financial security o tenure o administrative control (what cases they take on) Institutional independence is when you look at the agency set-up and its status makes you q if agency can make decisions independently of the political or the executive (e.g. does it operate independently of the Minister) The 5 main cases are: R. v. Valente SCC 1985 Canadian Pacific Ltd. v. Matsqui Indian Band SCC 1995 2747-3174 Quebec Inc. v. Quebec (Regie) SCC 1996 Ocean Port Hotel Ltd v. BC (LCB), SCC 2001 Bell Canada v. Canada Telephone Employees Association SCC 2003