Accountable Talk: The Importance of Wait-Time

advertisement

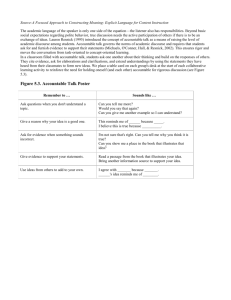

Accountable Talk: The Importance of Wait-Time The late Mary Budd Rowe made wait time a major focus of her work in science education. She studies included teaching in classrooms from elementary school to college, from special-education settings to the informal teaching that takes place in museums. Rowe found that “when teachers ask questions of students, they typically wait one second or less for the students to start a reply; after the student stops speaking teachers begin their reaction or ask the next questions in less than one second.” By contrast, “when teachers wait for three second or more, especially after a student response, there are pronounced changes in student use of language and logic as well as in student and teacher attitudes and expectations, (quoted in Cazden, 2001, p. 94). Here are some of the positive outcomes of increased wait time: 1. Teachers’ responses exhibit greater flexibility, indicated by the occurrence of fewer discourse errors and greater continuity in the development of ideas. 2. Teachers ask fewer questions, and more of them are cognitively complex. 3. Teachers become more adept at using student responses—possibly because they, too, are benefiting from the opportunity afforded by the increased time to listen to what students say. 4. Expectations for the performances of certain students seem to improve, and some previously invisible people become visible. 5. “Students are no longer restricted to responding to teacher questions and get to practice a variety of moves—soliciting, reacting, structuring, as well as responding,” (Cazden, 2001, p. 94, pp. 60-61). Importantly, the research on pacing of lessons suggests that increasing wait time “is easier to describe than to do.” Rose reports the kind of in-service supervision and support it requires, particularly if it is to be sustained and incorporated into the teacher’s routine enactment of her role. In Rowe’s words, “There are role and norm transformations taking place, and the teachers need a chance to talk about their experience of this change,” (quoted in Cazden 1988, p. 61). Clearly, in making a shift in wait time, teachers are doing far more than simply waiting longer. They are rethinking the kinds of questions and comments they formulate, and their expectations for student participation. References: Cazden, C.B. (1988). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Cazden, C.B. (2001). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Rowe, M.B. (1986). Wait time: Slowing down may be a way of speeding up! Journal of Teacher Education, 37, 43-50 Accountable Talk Classroom Conversations that Work @2002 University of Pittsburgh Accountable Talk: The Importance of Wait-Time Wait time after posing a question When the teacher asks a question, not all students will process that question at the same rate. Second language learners, students with less background knowledge, students with processing difficulties, all may be left behind if the teacher proceeds too quickly to choosing a student to answer her question. Often a student will quickly raise his or her hand, and it may feel strange to ignore that student and wait for others to respond. But consciously waiting be calling on anyone gives more students a chance to think and formulate a response. This technique has another, equally important effect. In many classrooms, students know that all of the teacher’s questions will be answered by a few “star students.” The “silent majority” feel no obligation to try and answer a question because they know that before they can formulate a response, one of the stars will beat them to it. Over time, this has a demoralizing effect on students and on the teacher. In such classrooms, it is difficult to sustain a discussion in which all students participate, and more importantly, students do not have to sense that they have an obligation to think about the problem or question along with everyone else. If a teacher uses the first kind of wait time consistently, and also varies the choice of students she calls on, a change will take place in the classroom. Students who formerly never volunteered an answer will begin to realize that the teacher’s questions are also for them. Wait time after calling on a student A second kind of wait time can be seen after the teacher has called on a student. Many students will take quite a while to answer. They may sit silently, staring at the teacher. They may begin to formulate an answer, stumbling and stopping in a way that is difficult to follow. It sometimes feels very uncomfortable to wait silently as a student struggles to formulate an answer. Most of us naturally want to jump in and rescue the student by offering to let them pass or soliciting another student’s help. Yet teachers who have gritted their teeth and remained silent, waiting for an answer of some kind, have come to see significant changes among their students. Many more students are willing to engage in the conversations. Teachers who use this kind of wait time effectively often explicitly tell the students that they are, in fact, waiting. As a student struggles to answer, they will say to other students things like, “That’s OK, give her time.” Or, “That’s OK, we’ll wait.” This kind of behavior models accountability to the community. Wait time after student gives a response A third kind of wait time emerges after the student has given a response. It is easy to forget that when a student produces an answer, not all of the other students will be able to process that answer equally quickly. The teacher can help by finding ways to extend the time that the student’s answer “hangs in the air.” For example, the teacher can thoughtfully repeat the student’s answer: “Hmmm, the fractions with odd denominators.” Some teachers take the step of writing an answer on the board, or slowly clarifying it in a revoicing move: “So, you’re saying that the fractions with odd denominators will be the ones that create repeating decimals. So Anna’s conjecture is that repeating decimals will result for all fractions with odd denominators. Is that right Anna?” Other teachers may ask another student to repeat what Anna has said. Although none of these moves involve silence, all are a form of “wait time,” because all give the students additional time to process what has been said. Accountable Talk Classroom Conversations that Work ©2002 University of Pittsburgh