Battle of Hastings: A Surprise Defeat

advertisement

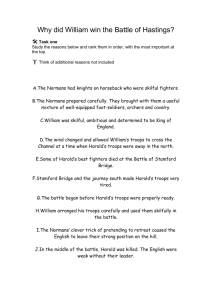

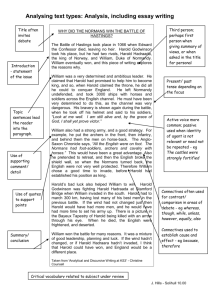

Battle of Hastings: A Surprise Defeat? By Michael Wood The Normans turned England upside down, as their army of occupation of some 20,000 men began their rule over a nation of maybe two million souls. How did they do it? No heirs apparent Less than a century after King Edgar's coronation at Bath Abbey in 973, the Anglo-Saxon state was overthrown by the Normans in 1066. But, importantly, its administrative structures were not swept away. And the fact that they remained meant that, in effect, the Anglo-Saxon state formed the basis of the Anglo-Norman and early modern English state. However, although the Normans took over the older machinery, they created an entirely new order. '... the invasion of 1066 was achieved by a very small army.' Considering what we know now about the power and wealth of the late Saxon state, its defeat at Hastings may seem to have been a surprising one. In fact, the invasion of 1066 was achieved by a very small army. William the Conqueror invaded England with fewer than 10,000 troops, perhaps as few as 7 or 8,000 initially. At the end of his reign, they only ever had, as an army of occupation, 20,000 men holding down a nation of one and a half or even two million souls. It's a bit like the British in India with 350,000 troops and administrators holding down 350 million people. And yet the Normans turned the country upside down. In part this was due to their own undoubted military skills. But they were also very lucky. Dynastic failure The situation came about through dynastic failure - the failure to secure the English succession. Ethelred the Unready had died in 1016 after a disastrous reign. He was succeeded by Canute (Cnut), the son of King Sweyn of Denmark. This marked the beginning of a period when England was ruled by Scandinavian kings and looked, once more, across the North Sea to its old connections with the Viking world. Then the Anglo-Saxon line was re-established by Ethelred's son Edward (the Confessor, who had been brought up in exile in Normandy). He came to the throne in 1042, but never had children. '... predatory wolves used to hang around waiting for such opportunities.' The dynastic crisis which everyone had anticipated finally came in January 1066, when Edward the Confessor died. If there was one thing a king should never do in the Dark Ages and early Middle Ages, it was to die without children. Succession crises were to be avoided at all costs because predatory wolves used to hang around waiting for such opportunities. William, Duke of Normandy was one such predator, and Harold Hardrada, King of Norway was another. Both looked at this, the richest country in western Europe, with its vast coinages and its great sheep fields and its big towns. It was a good prize. And unfortunately for the English, both went for it - at the same time. Harold the usurper Following Edward's death, Harold Godwinson, the Earl of Wessex, took the English throne. In some parts of the country he was perhaps viewed as a usurper. Certainly he was viewed as such by the Normans, who claimed that Harold had earlier promised to support Duke William's claim. Maybe he had - but surely only under duress. The Norwegians meanwhile had been approached by Harold's disaffected brother, Tostig. They planned an invasion of England together, and landed in early September in Yorkshire. 'Had William arrived on time, then, things might have gone very differently.' William assembled his fleet in August, planning his invasion in the south at just the same time. Had things gone differently, had the wind blown when expected, William would have probably landed in late August or early September. Then he would have found King Harold of England waiting on the south coast with a fresh army - including not only the thegns of England, but also a large number of mercenaries, and his Danish housecarls. Had William arrived on time, then, things might have gone very differently. But he was delayed, and in the meantime Harold Hardrada and Tostig landed in Yorkshire. They fought a battle near York, against the northern English. There were heavy casualties, but they succeeded in occupying York. King Harold of England heard the news, and took just five days to march his army up to Yorkshire, where he defeated the Norwegians in a terrible battle at Stamford Bridge. Harold then returned to York, only to hear the news that the wind had changed and the Normans had landed 260 miles to the south. Harold marched all the way back down south, with an army composed largely of his household troops and mercenaries. As one chronicle puts it: 'Except for his household troops and mercenaries ... he had very few people from the country.' On 14 October, he confronted William's army near Hastings. Fighting the wrong battle The strategy and the tactics of the Battle of Hastings have been the subject of much debate. Most likely Harold intended to launch a surprise attack on William,but for whatever reason, his forces did not make the rendez-vous on time, and he had to improvise a defensive position on a hill about seven miles from Hastings. It is inconceivable that Harold had intended to march all that way at breakneck speed only to fight a defensive battle, but that's what happened. In the end, of course, worn down by the Norman troops and their allies, the exhausted English army was broken and their king was killed - along with most of his nobles. It could so easily have been different. Would William have won if he had been met by Harold on the coast with a fresh army, instead of a battered remnant? '... Hastings really was the beginning of the end of Anglo-Saxon England' It's rare that one battle proves so decisive. Though resistance to the Norman conquerors went on for three years, especially in the north, Hastings really was the beginning of the end of Anglo-Saxon England. The surviving English nobles, and those who had not fought in the battle, offered William the crown. Among the many sources, English and Norman, that tell the story of the batle, the most beautiful and extraordinary is a 60m (200ft) -long embroidery, the Bayeux Tapestry, stitched for the victors by English needlewomen. We know it was created by English workers from the style, and the use of Anglo-Saxon letter forms. English needlework, opus Anglicanum, was highly sought after in the early Middle Ages. The Tapestry tells the story of the year 1066 - from Edward's last days to the Battle of Hastings. And although the final scene is missing today, there is little doubt it would have depicted Duke William of Normandy being crowned at Westminster Abbey, on Christmas Day, as Rex Anglorum, King of the English, the successor of Athelstan and Edgar. A new phase of English (and British) history had begun. About the author Michael Wood is the writer and presenter of many critically acclaimed television series, including In the Footsteps of...series. Born and educated in Manchester, Michael did postgraduate research on Anglo-Saxon history at Oxford. Since then he has made over 60 documentary films and written several best selling books. His films have centred on history, but have also included travel, politics and cultural history.