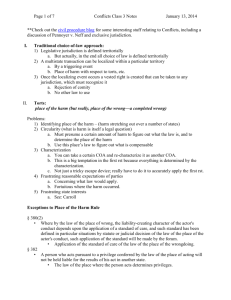

The Classification of Things A Précis I Common & Non

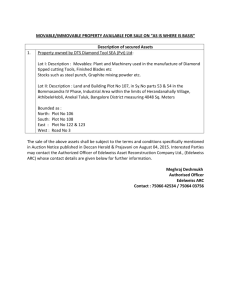

advertisement

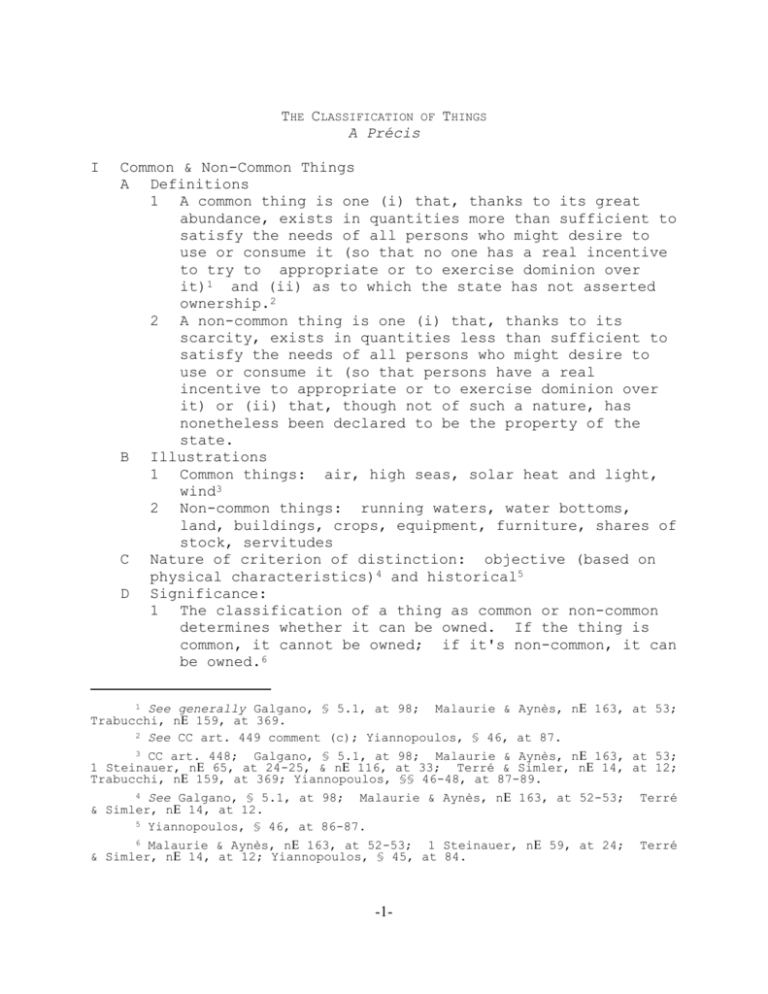

THE CLASSIFICATION OF THINGS A Précis I Common & Non-Common Things A Definitions 1 A common thing is one (i) that, thanks to its great abundance, exists in quantities more than sufficient to satisfy the needs of all persons who might desire to use or consume it (so that no one has a real incentive to try to appropriate or to exercise dominion over it)1 and (ii) as to which the state has not asserted ownership.2 2 A non-common thing is one (i) that, thanks to its scarcity, exists in quantities less than sufficient to satisfy the needs of all persons who might desire to use or consume it (so that persons have a real incentive to appropriate or to exercise dominion over it) or (ii) that, though not of such a nature, has nonetheless been declared to be the property of the state. B Illustrations 1 Common things: air, high seas, solar heat and light, wind3 2 Non-common things: running waters, water bottoms, land, buildings, crops, equipment, furniture, shares of stock, servitudes C Nature of criterion of distinction: objective (based on physical characteristics)4 and historical5 D Significance: 1 The classification of a thing as common or non-common determines whether it can be owned. If the thing is common, it cannot be owned; if it's non-common, it can be owned.6 1 See generally Galgano, § 5.1, at 98; Malaurie & Aynès, n 163, at 53; Trabucchi, n 159, at 369. 2 See CC art. 449 comment (c); Yiannopoulos, § 46, at 87. 3 CC art. 448; Galgano, § 5.1, at 98; Malaurie & Aynès, n 163, at 53; 1 Steinauer, n 65, at 24-25, & n 116, at 33; Terré & Simler, n 14, at 12; Trabucchi, n 159, at 369; Yiannopoulos, §§ 46-48, at 87-89. 4 See Galgano, § 5.1, at 98; Malaurie & Aynès, n 163, at 52-53; Terré & Simler, n 14, at 12. 5 Yiannopoulos, § 46, at 86-87. 6 Malaurie & Aynès, n 163, at 52-53; 1 Steinauer, n 59, at 24; Terré & Simler, n 14, at 12; Yiannopoulos, § 45, at 84. -1- 2 E Whereas common things can be used by everyone conformably with the use for which nature has intended them,7 non-common things may not be used freely by everyone, but are reserved for the use of a specific person or persons (e.g., the owner or the usufructuary). Subdivisions 1 Of Non-Common Things: Public & Private Things a Definitions 1) Public things are things that are owned by the state or its political subdivisions in their capacity as public persons.8 2) Private things are things that are owned by (i) natural or private juridical persons or (ii) the state or its political subdivisions in their capacity as private persons.9 b Illustrations 1) Public things: a) Of the state itself: running waters, waters and bottoms of natural navigable water bodies, territorial sea, seashore10 b) Of the state's political subdivisions: streets, public squares, parks, cemeteries, open spaces11 2) Private things: public offices, police & fire stations, publicly-owned markets, schoolhouses,12 houses, automobiles, clothes, books To say that a common thing "cannot be owned,” though technically accurate, nevertheless invites misunderstanding. This proposition is true of the common thing only in its entirety, e.g., the atmosphere as a whole or all of the high seas. It is not true, however, of discrete parts of the common thing. Thus, whereas one can't own the whole atmosphere, one can, by exercising dominion over a discrete part of it (e.g., bottling up a few cubic feet of air), become the owner of that part. See Terré & Simler, n 14, at 12; Trabucchi, n 159, at 369; Yiannopoulos, § 47, at 87. 7 CC arts. 448 & 452; Galgano, § 5.1, at 98; Malaurie & Aynès, n 163, at 52-53; 1 Steinauer, n 65, at 25; Terré & Simler, n 14, at 12; Yiannopoulos, § 46, at 86. 8 CC art. 450, ¶ 1; Yiannopoulos, § 49, at 89, & § 52, at 95-96. See generally Cornu, n 977, at 311-12; Galgano, § 5.4, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, n 164, at 54; Terré & Simler, n 538, at 344; Trimarchi, n 388, at 538. 9 CC art. 453; Yiannopoulos, § 49, at 89; § 52, at 95-96; § 59, at 106; § 61, at 107. 10 CC art. 450, ¶ 2; Galgano, § 5.4, at 113-14; Malaurie & Aynès, n 164, at 54 n. 41; Trabucchi, n 165, at 380; Trimarchi, n 388, at 538; Yiannopoulos, §§ 56-58, at 102-05. 11 CC art. 450, ¶ 2 & comment (e); Galgano, § 5.4, at 114; Trimarchi, n 388, at 538-39; Yiannopoulos, § 56, at 102. 12 CC art. 453 comment (b); Yiannopoulos, § 61, at 108. -2- 2 c) Significance 1) In general: The classification of a thing as public or private determines whether the thing can be owned by private persons (as opposed to governmental entities). If the thing is public, it cannot be owned by private persons (at least not so long as it remains public13); if it's private, then it can be owned by private persons.14 2) Particular applications: a) Whereas private things are susceptible of acquisitive prescription, public things are not.15 b) Whereas private things are susceptible of possession, public things are not.16 Of Public Things: Necessarily & Adventitiously Public Things a Definitions: 1) Necessarily Public Things: Necessarily public things are things that, according to constitutional or legislative provisions, are inalienable and necessarily owned by the state or its political subdivisions.17 2) Adventitiously Public Things: Adventitiously public things are things that, though alienable and thus susceptible of ownership by private persons, are presently (i) applied to some public purpose and (ii) held by the state or its political subdivisions in their capacity as public persons.18 b Illustrations 1) Necessarily public things: running waters, 13 Some public things are permanently public and, for that reason, can never be privately owned. But others are public only “for the time being.” The latter become susceptible of private ownership (in other words, private) when and if they cease to be public. For more on this topic, see the discussion of Necessarily & Adventitiously Public Things below. 14 Yiannopoulos, § 45, at 84. See also Galgano, § 5.4, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, n 164, at 54 & 55; 1 Steinauer, n 69-70, at 25-26; Trabucchi, n 165, at 380-81; Trimarchi, n 388, at 538. 15 Yiannopoulos, § 53, at 97, & § 54, at 98. See also Malaurie & Aynès, n 164, at 54 & 55; Trabucchi, n 165, at 380-81; Trimarchi, n 388, at 538. 16 Trabucchi, n 165, at 138. 17 CC art. 450 comment (c), ¶ 2; see also Galgano, § 5.4, at 113-114; Trabucchi, n 165, at 380; Trimarchi, n 388, at 538. 18 CC art. 450 comment (c), ¶ 3; see also Trimarchi, n 388, at 539. -3- c seashore, waters & bottoms of the Gulf of Mexico within Louisiana's borders, bottoms of navigable waterways19 2) Adventitiously public things: public squares, publicly-owned roads, public parks, public drainage ditches, cemeteries, publicly-owned markets20 Significance: The classification of a thing as necessarily or adventitiously public determines the duration of its insusceptibility to private ownership. If the thing is necessarily public, then it's public once and for all: it can never cease to be public and, therefore, can never become private.21 If the thing is merely adventitiously public, by contrast, then its public status can end and when and if that happens, it becomes private.22 II Corporeals & Incorporeals A Definitions 1 Corporeal things are things that have a body or physical form and that can therefore be felt and touched.23 2 Incorporeal things are things (i) that have no body or physical form, that is, that cannot be felt or touched, or (ii) that are comprehended by the understanding.24 B Illustrations 1 Corporeal things: land, buildings, crops, equipment, furniture, petroleum, water, air25 2 Incorporeal things: rights of inheritance, personal servitudes (e.g., usufruct, habitation), predial 19 CC art. 450 comments (d) & (g); see also Galgano, § 5.4, at 113-14; Trabucchi, n 165, at 138; Trimarchi, n 388, at 539. 20 Trimarchi, n 388, at 538-39. 21 Short of a change in the law, that is. As we have learned, a thing is necessarily public if and only if the constitution, legislation, or other provision of law dictates public ownership. Those provisions of law, of course, are not themselves immutable. If the people (in the case of a constitutional provision) or the government (in the case of legislation or other second order provision of law) were to repeal such a law or otherwise change it so that public ownership was no longer required, then the thing to which that law applies would, of course, cease to be necessarily public and become, instead, only adventitiously public or private, depending on what the new constitutional, legislative, or other legal provision dictates. 22 Yiannopoulos, § 53, at 97-98 & n. 4; see also Galgano, § 5.4, at 114. 23 CC art. 461, ¶ 1; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 44. 24 CC art. 461, ¶ 2; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 44-45. 25 Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 44. -4- C D servitudes, mineral rights, petitory actions, posessory actions, bonds, shares of stock, obligations (e.g., tort rights and contract rights), right of intellectual property26 Nature of criterion of distinction: physical27 Significance 1 Property law a Possession: Only corporeals are susceptible of "possession," at least in the original sense of the term and as its used in the current Civil Code.28 b Servitudes: domain: Only corporeals--corporeal immovables, to be more precise--can be subjected to predial servitudes and the personal servitudes of right of use and habitation.29 Incorporeals cannot. 2 Others: law of obligations: contracts a Donations inter vivos: donative formalties: Incorporeals can be donated only by means of authentic act.30 Certain corporeals--corporeal 26 CC art. 461, ¶ 2; Cornu, nn 912-14, at 296-97; nn 917-18, at 29899; & n 926, at 301. Terré & Simler, n 26, at 22-23, & n 31, at 27; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 44-45. The status of things that, according to modern physics, have some sort of physical existence (i.e., exist in time and space and are susceptible of detection, measurement, etc.), but whose physical existence is not readily perceptible by the unaided human senses, e.g., energy (electrical, nuclear, etc.), power, radioactivity, is not entirely clear. On the one hand, these things do not "have a body" in the common sense of the word "body." But on the other, they are not purely ideational or conceptual entities (referents of "abstract nouns") like "rights," or "property," or "interests," and so, are not comprehended solely by the understanding. 27 Malaurie & Aynès, n 200, at 57; see generally Yiannopoulos, § 25, at 43, & § 26, at 44. 28 CC art. 3421, ¶ 1; Cornu, n 1426, at 455; Malaurie & Aynès, n 207, at 61; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 46 & n. 18. To be sure, some (though not all) incorporeals are susceptible of what the Civil Code calls "quasi-possession," which is supposedly "analogous" to possession. CC art. 3421, ¶ 2. This analogy, however, is sometimes a strained one. In modern French doctrine, the distinction between possession and quasi-possession has been dissolved or, to invoke another metaphor that’s perhaps more descriptive, quasi-possession has been absorbed into possession. Possession, as redefined, means the factual exercise of some real right (such as ownership or a servitude)–an incorporeal--with the intent to comport oneself as the title-holder of that right. Cornu, nn 1131-1132, at 356; Malaurie & Aynès, n 492, at 128; Terré & Simler, n 138, at 101, & n 140, at 101-02; see also TRAVAUX DE LA COMMISSION DE RÉFORME DU CODE CIVIL, Le Projet du Livre des Biens 640, 642, 659, 956, 957, 1001 (1946-47); CODE CIVIL DU QUÉBEC art. 921 (“Possession is the factual exercise, by oneself or by the intermediation of another person who detains the thing, of a real right of which one wants to be the title-holder.”) 29 CC art. 698; Terré & Simler, n 796, at 561; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 46 & n. 18. 30 CC art. 1536; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 46. An authentic act is a written instrument executed before a notary and two witnesses. CC art. 1833. -5- b movables, to be precise--can be donated by means of physical delivery, which the Code refers to as "manual gift."31 Sales: mode of delivery: Corporeal movables that have been sold have to be delivered physically, that is, handed over by seller to buyer.32 Incorporeals, by contrast, are considered to be delivered as of the moment at which the instrument that represents them is negotiated or at which the agreement to transfer them is finalized.33 III Consumables & Nonconsumables A Definitions: 1 Consumables are things that, by nature or by destination, cannot be used without being expended, consumed, or alienated or without their substance being changed.34 2 Non-consumables are things that, by nature or by destination, may be enjoyed without being expended, consumed, or alienated and without alteration of their substance (aside from normal “wear and tear” associated with the use to which they are applied).35 They continue to exist in spite of prolonged use.36 B Illustrations 1 Consumable things: money, harvested agricultural products, stocks of merchandise, foodstuffs, beverages, fuels, negotiable instruments payable to bearer, certificates of deposit37 2 Nonconsumable things: lands, houses, shares of stock, animals, furniture, vehicles, jewelry, clothes, CC art. 1539; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 46.. CC art. 2477, ¶ 2. 33 CC art. 2481; Yiannopoulos, § 26, at 46 & n. 18. 34 CC art. 536; Cornu, n 941, at 304; Galgano, § 5.3, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, n 152, at 47; 1 Steinauer, n 105, at 31; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trabucchi, n 161, at 373; Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Yiannopoulos, § 28, at 47. 35 CC art. 537; Cornu, n 942, at 304; Galgano, § 5.3, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, n 152, at 47; Trabucchi, n 165, at 373; Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Yiannopoulos, § 28, at 47. 36 Yiannopoulos, § 28, at 47-48; see also Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13. 37 CC art. 536; Cornu, n 941, at 304; Galgano, § 5.3, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, n 152, at 47; 1 Steinauer, n 106, at 31; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trabucchi, n 165, at 373; Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Yiannopoulos, § 28, at 47 & 49. 31 32 -6- C D machines38 Nature of the criterion of distinction: primarily objective (based on physical characteristics), though subjective factors (intended destination) can sometimes be relevant39 Significance 1 Property law: real rights: servitudes: usufruct: A usufruct whose object is a non-consumable (traditionally known as a perfect usufruct) and a usufruct whose object is a consumable (traditionally known as an imperfect usufruct) are subject to quite different legal regimes.40 To take two examples: a Whereas the usufructuary of a non-consumable cannot alienate or encumber the thing, the usufructuary of a consumable can.41 b At the termination of a usufruct on nonconsumables, the usufructuary (or his successor) must deliver the non-consumables themselves to the owner (former naked owner)42; at the termination of a usufruct on consumables, by contrast, the usufructary (or his successor) must deliver to the owner (former naked owner) either (i) things of the same quantity and quality as the consumables or (ii) the value of the consumables as of the inception of the usufruct.43 2 Others: obligations: contract: nominate contracts: 38 CC art. 537; Cornu, n 942, at 304; Galgano, § 5.3, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, n 152, at 47; 1 Steinauer, n 106, at 31; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trabucchi, n 165, at 373; Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Yiannopoulos, § 28, at 48 & 49. 39 Yiannopoulos, § 28, at 48-49. 40 See, e.g., CC arts. 538-539 & 628-629; see also Cornu, n 944, at 305; Galgano, § 8.3, at 158-59; Malaurie & Aynès, n 153, at 47; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trabucchi, n 161, at 373; Trimarchi, n 405, at 562. 41 CC arts. 538-39; Cornu, n 944, at 305, & n 1276, at 401; Malaurie & Aynès, n 813, at 232; 3 Steinauer, n 2405, at 19; n 2411, at 20; & nn 2484-2485, at 44; Terré & Simler, n 733, at 517-18; Trabucchi, n 202, at 464; Trimarchi, n 405, at 562. 42 CC art. 628; Cornu, n 1314, at 411; Malaurie & Aynès, n 834, at 244; Terré & Simler, n 780, at 551; Trimarchi, n 60, at 109, & n 405, at 562. 43 CC art. 629; Cornu, n 944, at 305, & n 1276, at 401; Galgano, § 8.3, at 158 & 159; Malaurie & Aynès, n 834, at 244; 3 Steinauer, n 2485a, at 44; Terré & Simler, n 782, at 551-52; Trabucchi, n 161, at 373, & n 202, at 464; Trimarchi, n 405, at 562. -7- loans: Whereas only consumable things may be the object of a mutuum (loan for consumption)44, only nonconsumable things may be the object of a commodatum (loan for use).45 IV Fungibles & Infungibles A Definitions 1 Fungibles: Two or more things are fungible vis-à-vis each other46 if they belong to the same genre of things and if, by virtue of their physical characteristics or the intention of those who deal with them, they are interchangeable or substitutable one for the other in view of the end for which they will be used.47 In commercial transactions, they are ordinarily bought and sold or otherwise traded by numbers, weight, or measure.48 2 Infungibles: An infungible is a thing that, by virtue of its physical characteristics or the intention of those who are dealing with it, is unique in view of the end for which it will be used, so that it cannot be replaced by or interchanged with any other thing.49 CC arts. 2891, ¶¶ 3 & 5, & 2910. CC arts. 2891, ¶¶ 2 & 4, & 2893. See Cornu, n 945, at 305; Malaurie & Aynès, n 153, at 47; 1 Steinauer, n 107, at 31; Trimarchi, n 60, at 109. 46 The importance of the phrase “vis-à-vis each other” in this definition cannot be overemphasized. It indicates that “fungibility,” unlike many of the other characteristics on the basis of which things are classified (e.g, corporeality, consumability, or immovability), is a “relational” characteristic, that is, it presents itself only if and when one thing is juxtaposed against and compared with another. Just as it makes no sense to ask “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” it makes no sense to ask “Is this single thing fungible in itself?” See generally Malaurie & Aynès, at 48; Trabucchi, n 162, at 374-77. 47 See Yiannopoulos, § 29, at 50; see also Cornu, n 946, at 305; Galgano, § 5.3, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, at 48; 1 Steinauer, n 98, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trabucchi, n 161, at 372; Trimarchi, n 60, at 107. See also Avant-Projet << Biens>> art. 16, Les Travaux de la Commission de Réforme du Code Civil 658 . 48 Galgano, § 5.3, at 113; Malaurie & Aynès, n 155, at 48; 1 Steinauer, n 98, at 30; Trabucchi, n 161, at 372; Yiannopoulos, § 29, at 50; Avant-Projet << Biens>> art. 16, Les Travaux de la Commission de Réforme du Code Civil 658 ; BGB art. 91. 49 Yiannopoulos, § 29, at 50; see Cornu, n 946, at 303; Galgano, § 5.3, at 113; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trabucchi,n 161, at 372; Trimarchi, n 60, at 107. 44 45 -8- B Illustrations 1 Fungibles: agricultural products (a dozen eggs, 50 kilos of rice, 20 "head" of cattle), mineral products (e.g., a barrel of petroleum or 20 liters of gasoline), chemical substances (30 Viagara tablets), foodstuffs (10 boxes of Rice-a-Roni), drinks (50 cases of Abita Purple Haze), products in a series, provided they are new (e.g., 5 copies of Gore Vidal's latest novel or Madonna's latest CD; 100 Ronco Bass-o-Matics, 10 "fully-loaded" 1999 Yugos), money, financial instruments that are the equivalent of money50 2 Infungibles: a family heirloom, a country house, a race horse, a master board, a collection of prizes, a period furniture piece, a numbered exemplar of a deluxe edition, a collection of rare coins, a garment made to measure, a piece of furniture fabricated by a craftsman according to a particular design, the originals of nonmultiple works of art, all used things, land 51 Nature of criterion of distinction: partly objective (based on physical characteristics) & partly subjective (based on intended use)52 Significance: 1 Obligations law: sales: transfer of ownership: Whereas the ownership of a infungible thing is transferred from the seller to the buyer as soon as they agree on the thing and the price (even if delivery is postponed),53 the ownership of an fungible thing is transferred only when the seller individualizes the thing (picks it out)54 or weighs, counts, or measures out the required quantity of the thing from his stock C D See Cornu, n 948, at 305; Galgano, § 5.3, at 112-13; Malaurie & Aynès, n 155, at 49; 1 Steinauer, n 98, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trabucchi, n 161, at 372; Trimarchi, n 60, at 107, 108. 51 See Cornu, n 948, at 305; Galgano, § 5.3, at 112; Malaurie & Aynès, n 156, at 49; 1 Steinauer, n 98, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13; Trimarchi, n 60, at 108. Why land? "[E]ven if two tracts of land of an equal nature differ only a little in terms of their location in space, their quality is almost never a matter of indifference." Trimarchi, n 60, at 108. 52 See Cornu, n 949, at 303; Malaurie & Aynès, nn 155-156, at 48-49; Terré & Simler, n 15, at 14. 53 CC art. 2456. 54 Id. art. 2457. 50 -9- 2 3 V of things of the same kind.55 Obligations law: modes of extinguishing obligations: performance: In a case in the which the obligor owes a duty to give or to deliver, the qualification of the object of that duty as fungible or infungible will determine what performance is due and, so, what the obligor must do to extinguish the obligation through performance. If the object of that duty is a infungible, then the obligor must give or deliver that particular thing, whereas if the object of that duty is a fungible, then the obligor need only (and, indeed, can only) give or deliver some (any) thing that conforms to the generic description of that fungible.56 Obligations law: modes of extinguishing obligations: compensation: Whereas reciprocal debts for the payment of things that are, as between themselves, fungible are susceptible of compensation, reciprocal debts for the payment of things that are, as between themselves, infungible are not.57 Divisible & Indivisible Things A Definitions 1 Divisible things: A thing is divisible if it can be physically divided into several discrete parts, provided that (i) the parts can be used for the same purposes as the undivided thing, (ii) the parts are of the same nature, (iii) the parts are of nearly equal value, and (iii) the aggregate value of the parts is not significantly less than the value of the undivided thing.58 2 Indivisible things: A thing is indivisible if (i) it cannot be physically divided into discrete parts or (ii) though it can be so divided, (a) the parts can’t be used for the same purposes as the undivided thing, (b) the parts are not of the same nature, (c) the parts are not of the same value, or (d) the aggregate value 55 at 50; 56 Id. art. 2458. See Cornu, n 952, at 304; Malaurie & Aynès, n 157, Terré & Simler, n 15, at 13. See Cornu, 950, at 303-04; see generally Malaurie & Aynès, n 157, at 49. CC art. 1893; see also Cornu, n 951, at 304; Malaurie & Aynès, n 157, at 49; Trabucchi, n 161, at 373. 58 1 Steinauer, n 108, at 31; Trabucchi, n 61, at 373; Yiannopoulos, § 30, at 53 (citing CC art. 810). 57 -10- of the parts is significantly less than the value of the undivided thing.59 Illustrations 1 Divisible things: undeveloped land, liquids, pieces of cloth, a slaughtered animal, a lot of merchandise, a sum of money60 2 Indivisible things: a living animal, a work of art, a clock, a diamond, the roof or foundation of a building61 Nature of criterion of distinction: objective (partly physical, partly economic) Significance: Whereas a co-owned divisible thing can be partitioned in kind (as well as by licitation),62 a coowned indivisible thing can be partitioned only by licitation, that is, it must be sold at public auction and the proceeds of the sale, divided among the co-owners.63 B C D VI Single (Simple) & Composite (Complex) Things A Definitions 1 Single things: A single (or simple) thing is a corporeal thing that, to the mind of a layman (as opposed to that of a scientist), appears to be composed of a single substance or to have a single essence.64 It's seemingly singular character may be attributable to nature or to man.65 2 Composite things: A composite (or complex) thing is a corporeal thing formed by the union of several corporeal things that, prior to this union, enjoyed a distinct physical existence, but that, by virtue of this union, seem to have lost their individuality and to have become but "component parts" (albeit essential ones) of a larger totality.66 If any of these component parts were to be separated from the rest, then the thing formed by their union would, to the mind See authorities 1 Steinauer, n 61 1 Steinauer, n 62 CC art. 810. 63 Id. art. 811. 64 1 Steinauer, n 65 1 Steinauer, n 66 Galgano, § 5.3, 31, at 55. 59 60 collected in previous note. 108, at 31-32; Trabucchi, n 161, at 373. 108, at 31-32; Trabucchi, n 161, at 373. 111, at 32; Yiannopoulos, § 31, at 55. 111, at 32. at 112; 1 Steinauer, n 111, at 32; Yiannopoulos, § -11- of a layman, be lost or destroyed.67 Illustrations 1 Single things: stones, pieces of metal, wood, organic matter, an animal, a plant, a piece of paper, a coin68 2 Composite things: a piece of furniture, a car, a ship, an automobile, an armoire, a developed immovable69 Nature of the criterion of distinction: objective (based on a scientifically naive assessment of physical characteristics) Significance: property & obligations law: transfer & encumbrance: The transfer or encumbrance of an immovable includes its component parts.70 B C D VII Principal Things & Accessory Things (Appurtenances) A Definitions 1 An accessory (or appurtenance) is a thing that, by its nature, local usage, or the intention of its owner, is dedicated on an enduring basis to the service, preservation, ornamentation, or economic use of another thing, called the principal, but that nevertheless, despite this dedication, neither loses its individuality so as to become a component part of the principal nor undergoes significant physical modification.71 2 The principal thing is the thing to which the accessory appertains.72 B Illustrations 1 The spare tire and tire tools of a car (the principal) are the car’s accessories73 2 The furniture in the lobby of a hotel (the principal) is an accessory of the hotel74 3 A free-standing garage is an accessory of a house (the Galgano, § 5.3, at 112. 1 Steinauer, n 111, at 32; Yiannopoulos, § 31, at 55. 69 Galgano, § 5.3, at 112; 1 Steinauer, n 111, at 32; Yiannopoulos, § 31, at 55. 70 CC art. 469. See Yiannopoulos, § 32, at 57. 71 Galgano, § 5.3, at 111 & 112; 1 Steinauer, n 94, at 29; Trabucchi, n 162, at 376; Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Yiannopoulos, § 34, at 59; BGB art. 97. 72 See authorities collected in previous note. 73 Trimarchi, n 60, at 109. 74 Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Galgano, § 5.3, at 111. 67 68 -12- principal)75 4 The service boats, life boats, furnishings, boarding devices, and tools of a ship (the principal) are the ship’s accessories76 5 A statue placed in a garden (the principal) is an accessory of that garden77 6 The accessories of a farm (the principal) may include tools, irrigation devices, seeds, fodder for animals78 7 The accessories of a church building (the principal) include pews, candelabras, religious ornaments (e.g., a crucifix or an icon)79 8 A water heater is an accessory of a building (the principal) 180 Nature of the criterion of distinction: partly objective (based both on physical characteristics and economic relationship of the things) and partly subjective (based on destination of the owner) Significance 1 Property law: accession: movables: When two corporeal movables that are, as between each other, principal and accessory, are "united" to each other, the whole becomes the property of the owner of the principal, who then owes a duty of reimbursement to the former owner of the accessory.81 2 Property & obligations law: ownership & sales: transfer: The sale of a thing includes all accessories intended for its use in accordance with the law of property.82 C D X Fruits & Products A Definitions 1 Fruits a In general: 75 Fruits are things that are produced by Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Galgano, § 5.3, at 111; Trabucchi, n 162, at 376. Trimarchi, n 60, at 109; Galgano, § 5.3, at 111. Galgano, § 5.3, at 111. 78 Trabucchi, n 162, at 376. 79 Id. 80 Id. In Louisiana, a water heater probably also qualifies as a component part by law of the building to which it’s attached. See CC art. 466, ¶ 1. 76 77 81 CC arts. 508 & 510. 82 CC art. 2461. -13- 1) 2 or derived from another thing without, in the process, noticeably diminishing or altering the substance of that thing.83 Though a thing need not be susceptible of periodic reproduction in perpetuity in order to qualify as a fruit, the vast majority of fruits do exhibit this characteristic.84 b Varieties: Natural: Natural fruits are those that, with or without human assistance or intervention, are derived or produced from the earth, from animals, or from plants by means of natural processes (e.g., sexual reproduction, germination, growth of tissue, generation of bodily fluids).85 2) Civil: Civil fruits are revenues derived from a thing by operation of law or by reason of a juridical act.86 Products a In general: Mere products are things that are produced or derived from another thing and that, in the process, diminish the substance of that thing.87 Such things usually are not susceptible of periodic reproduction, at least not indefinitely (in other words, if the process of production continues, the underlying thing will eventually run out).88 b Varieties CC art. 551, ¶ 1; see Yiannopoulos, § 39, at 70; see also Cornu, n 969, at 307; Malaurie & Aynès, n 160, at 52; Terré & Simler, n 16, at 14, & n 110, at 81. 84 Cf. Cornu, n 969, at 307; Malaurie & Aynès, n 160, at 52; 1 Steinauer, n 1073-1073a, at 278; Terré & Simler, n 16, at 14. 85 See CC art. 551, ¶ 3. See Yiannopoulos, § 40, at 72; see also Malaurie & Aynès, n 160, at 52; 1 Steinauer, nn 1072, 1073 & 1074, at 278; Terré & Simler, n 110, at 81; see generally Cornu, n 969, at 307; Galgano, § 5.2, at 103; Trabucchi, n 164, at 379; Trimarchi, n 60, at 110. 86 CC art. 551, ¶ 4. See Yiannopoulos, § 40, at 72; see also Malaurie & Aynès, n 160, at 52; 1 Steinauer, n 1076, at 279; Terré & Simler, n 110, at 81; see generally Galgano, § 5.2, at 103; Trabucchi, n 164, at 379; Trimarchi, n 60, at 110. 87 CC art. 488. See Yiannopoulos, § 39, at 70-71; see also Cornu, 970, at 308; Malaurie & Aynès, n 160, at 52; Terré & Simler, n 16, at 14, & n 110, at 81. 88 See Cornu, 970, at 308; Malaurie & Aynès, n 160, at 52; Terré & Simler, n 16, at 14, & n 110, at 81; see generally Yiannopoulos, § 39, at 70. 83 -14- 1) Natural products are those that, prior to their derivation or production, were part and parcel of or, at the very least, physically united to the thing from which they were derived or produced. 2) Civil products are revenues generated by the transfer of the right to remove natural products or by the sale of those natural products themselves. Illustrations 1 Fruits a Natural: fruits of trees, vines, and bushes (e.g., pears, satsumas, grapes, blackberries, strawberries); nuts (e.g., pecans); crops (e.g., rice, sugar cane, soybeans, water melons); 89 offspring of animals; milk; wool; trees, provided they are produced from an established tree farm or a regularly exploited forest; minerals (e.g., oil and gas), provided they are produced from an open mine90 b Civil: rent, interest, stock dividends91 2 Products a Natural: trees, provided they are not part of a tree farm or regularly exploited forest; minerals (e.g., oil and gas) produced from a new mine92 b Civil: revenues generated from the sale of timber rights or from the sale of timber itself, provided that the timber is not part of a tree farm or a regularly exploited forest; mineral (e.g., oil and gas) royalties payable upon production of minerals from a new mine Nature of the criterion of distinction: primarily B C CC art. 551, ¶ 3; Cornu, n 970, at 308; Galgano, § 5.2, at 103; 1 Steinauer, nn 1073 & 1075, at 278 & 279; Terré & Simler, n 110, at 81; Trabucchi, n 164, at 379; Trimarchi, n 60, at 110. 90 CC art. 551 comments (b) & (c); Yiannopoulos, § 42, at 73-76; see also Cornu, n 970, at 308; Malaurie & Aynès, n 161, at 52; Terré & Simler, n 110, at 81. 91 CC art. 551, ¶ 4; see Yiannopoulos, § 40, at 72: see also Cornu, 969, at 307; Galgano, § 5.2, at 103; Terré & Simler, n 110, at 81; Trabucchi, n 164, at 379; Trimarchi, n 60, at 110. 92 CC arts. 551 comments (b) & (c) & 448 comment (b); Yiannopoulos, § 42, at 73-76; see also Cornu, n 970, at 308; Malaurie & Aynès, n 161, at 52; Terré & Simler, n 110, at 81. 89 -15- objective (based on physical characteristics), secondarily subjective (deliberate alteration of the circumstances of production, e.g., drawing and implementation of plans for tree forests or mines)93 Significance: property law: ownership: accession with respect to fruits & products 1 Products belong to the owner of the thing from which they are produced.94 To this rule there are no exceptions. 2 Fruits, too, ordinarily belong to the owner of the thing from which they are produced.95 But to this rule, which is merely a general rule, there are exceptions: a Fruits produced by one who holds a usufruct over the underlying thing belong to the usufructuary.96 b Fruits gathered by one who possesses the underlying thing in good faith belong to the possessor.97 c Fruits produced from plantings made with the consent of a landowner belong to the planter, e.g., the lessee of a farm lease.98 D XI Immovables & Movables A Definitions 1 Immovable: Immovable things are (i) corporeal things (a) that are not susceptible of being moved from place to place or (b) that, by legislative fiat or by declaration of the owner, have been assimilated to such corporeal things and (ii) incorporeal things that have See Malaurie & Aynès, n 160, at 51; Terré & Simler, n 110, at 81. CC art. 488; see Yiannopoulos, § 39, at 70; see also Malaurie & Aynès, n 162, at 52; Terré & Simler, n 16, at 14. This assumes that the owner has not disposed of his right to the products by juridical act. If he has, then the products, of course, belong to his transferee. 95 CC art. 483; see Yiannopoulos, § 39, at 71, & § 42, at 75; see also Malaurie & Aynès, n 162, at 52. This assumes that the owner has not disposed of his right to the fruits by juridical act. If he has, then the fruits, of course, belong to his transferee. 96 CC arts. 550 & 483 comment (c); see Yiannopoulos, § 39, at 71, & § 42, at 74; see also Cornu, n 972, at 308l Malaurie & Aynès, n 162, at 52; Terré & Simler, n 16, at 14. 97 CC arts. 487 & 483 comment (c); see Yiannopoulos, § 42, at 75-76; see also Cornu, n 972, at 308; Malaurie & Aynès, n 162, at 52; Trabucchi, n 164, at 379. 98 Implication of CC art. 493, ¶ 1. See also CC art. 493 comment (c) (1984); CC art. 483 comment (c). 93 94 -16- such corporeal things as their objects.99 2 Movable: Movable things are those things that are not immovable.100 Classifications 1 Immovables a Corporeal immovables 1) Definition: Corporeal immovables are corporeals that are not susceptible of being moved from place to place or that, by legislative fiat or by declaration of the owner, have been 101 assimilated to such corporeal things. 2) Varieties a) By nature102 1] Things whose immovability is independent of unity of ownership a] Tracts of land103: portions of the surface of the earth individualized by boundaries, together with the soil and subsoil104 b] Buildings105: constructions that the society at large would regard as “buildings” in view of their B See Trabucchi, n 160, at 370 & 371; see generally Cornu, nn 921924, at 298-99; Malaurie & Aynès, n 110, at 29, & n 117, at 32; 1 Steinauer, n 96, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 17, at 15; Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 238, & § 108, at 239. 100 CC art. 475. See Yiannopoulos, § ___, at ___. See also Galgano, § 5.3, at 110; Malaurie & Aynès, n 117, at 32; Trabucchi, n 160, at 371; Trimarchi, n 60, at 106. 101 See Cornu, nn 921-924, at 298-99; Malaurie & Aynès, n 110, at 29, & nn 115-116, at 31-32, & n 117, at 32; Terré & Simler, n 17, at 15; Trabucchi, n 160, at 370; see generally Yiannopoulos, § 108, at 239, 240. 102 See generally Cornu, n 907, at 292-93; Terré & Simler, n 10, at 17; Trabucchi, n 160, at 370; Yiannopoulos, § 108, at 240, & § 112, at 255-56. 103 CC art. 462. See also Cornu, 907, at 292; Galgano, § 5.3, at 109; 1 Steinauer, n 96, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 20, at 17; Trabucchi, n 160, at 370; Trimarchi, n 60, at 106; Yiannopoulos, § 114, at 260-61. 104 CC art. 462 comment (c); see 1 Steinauer, n 96, at 30; Yiannopoulos, § 114, at 260; see also Terré & Simler, n 20, at 17. 105 CC arts. 463, 462, & 464. See also Cornu, n 907, at 292; Galgano, § 5.3, at 109; Terré & Simler, n 20, at 17; Trabucchi, n 160, at 370; Trimarchi, n 60, at 106; Yiannopoulos, § 114, at 262-63, & § 137, at 30405. 99 -17- permanence, function, size, and cost106 c] Standing timber107: 1} Standing: a} Rooted in the soil of the land108 b} Not cut down109 2} Timber: vegetation whose wood can be exploited for commercial purposes, e.g., the construction of buildings, other constructions, or furniture or the manufacture of paper110 d] Things so incorporated into a tract of land, a building, or an immovable construction so as to become an 111 integral part of it 1} Definition: One thing is so incorporated into another so as to become an integral part of the latter when the former, by virtue of the incorporation, loses its separate identity, merging with and becoming part and parcel of the latter.112 2} Illustrations: a} Building materials, e.g., paint, lumber, nails, sheetrock, bricks, mortar113 b} Structural additions to buildings, e.g., balconies, elevators and lifts, 114 partitions, mezzanines e] Things permanently attached to a building or some other immovable Yiannopoulos, § 137, at 304-05. CC arts. 463, 462, & 464. See Yiannopoulos, § 133, at 299. 108 Cf. Yiannopoulos, § 128, at 287 n. 1. 109 CC art. 463 comment (d); Yiannopoulos, § 134, at 299. 110 CC art. 562 comment (c). 111 CC arts. 465, 462, 463 & 464. See Yiannopoulos, § 115, at 263, & § 142, at 312-13. 112 CC art. 465 comment (c); Yiannopoulos, § 115, at 263, & § 142, at 312-13. 113 CC art. 465; Yiannopoulos, § 142, at 312. 114 Yiannopoulos, § 142, at 313. 106 107 -18- construction so as to become component parts of it115 1} Things permanently attached as a matter of law116 a} Definition: A thing is permanently attached to a building or another immovable construction as a matter of law if the society at large would regard it as such, in other words, if reasonable persons would assume that the thing “is part of” or “goes with” the building or other construction.117 b} Illustrations: light fixtures (including, at least in some instances, chandeliers), carpeting, tile flooring, wall paper, ceiling fans, burglar alarms, septic tanks, field lines, air-conditioning units118 2} Things permanently attached as a matter of fact119 A thing is permanently attached to a building or another immovable construction as a matter of fact if it cannot be removed without causing the building or other construction to sustain substantial physical damage.120 2] Things whose immovability is dependent on unity of ownership a] Other constructions permanently attached to the ground121 CC art. 466, 463, 462 & 464. See Yiannopoulos, § 142, at 312. Id. ¶ 1; Yiannopoulos, § 142, at 313. 117 Equibank v. IRS, 749 F.2d 1176 (5th Cir. 1985); American Bank & Trust Co. v. Shel-Boze, Inc.., 527 So. 2d 1052 (La. App. 1st Cir. 1988). 118 See authorities collected in Yiannopoulos, § 142, at 313 n. 4 (and Supplement). 119 CC art. 466, ¶ 2; Yiannopoulos, § 142, at 313-14. 120 CC art. 466, ¶ 2; Yiannopoulos, § 142, at 313-14. 121 CC art. 463 & 462. See Yiannopoulos, § 141, at 309-10. 115 116 -19- 1} Construction: any man-made structure 2} Other: not a building122 3} Permanently attached to the ground: physically integrated into the soil in a manner which suggests that the thing so integrated will remain there on an enduring basis123 b] Unharvested crops124 1} Unharvested: still attached to the stalk or stem, which, in turn, is still rooted in the soil of the land125 2} Crop: vegetation grown for consumption, either by the grower himself or by someone else c] Ungathered fruits126 1} Ungathered: still hanging on the vine or branch 2} Fruit: a sweet, edible plant part that contains the plant's seeds inside a juicy pulp b) By declaration: Certain movables may be "immobilized" by a declaration of the will on the following conditions127: 1] the movable qualifies as machinery, an appliance, or equipment; 2] it is placed on and dedicated to the service and improvement of an immovable; 3] the dedicator owns the movable; 4] the dedicator also owns the immovable; 5] the dedicator declares in writing that he has placed the movable on the immovable for its service and improvement so as to make the movable a component part of the immovable; Yiannopoulos, § 141, at 309. Yiannopoulos, § 141, at 310 & 311 n. 11. 124 CC art. 463. See Yiannopoulos, § 115, at 262-63, & § 128, at 287. 125 See generally Yiannopoulos, § 128, at 287 n. 2. 126 CC art. 463. See Yiannopoulos, § 115, at 262-63, & § 128, at 287. 127 CC art. 467. See Yiannopoulos, § 115, at 263, & § 142, at 31. Cf. Cornu, 908-911, at 293-94 (immovables by destination); Malaurie & Aynès, at 42-45 (same); Terré & Simler, nn 21-24, at 18-21 (same). 122 123 -20- 2 6] the written declaration is filed for registry in the appropriate public records b Incorporeal immovables 1) Definition: Incorporeal immovables are rights and actions that apply to immovable things.128 2) Illustrations: personal servitudes established on immovables, predial servitudes, mineral rights, petitory actions, possessory actions129 Movables a Corporeal movables 1) Definition: Corporeal movables are things, whether animate or inanimate, that (i) normally move or can be moved from one place to another and (ii) have not been immobilized.130 2) Varieties: a) Corporeal movables neither attached nor dedicated to an immovable * Examples: harvested crops, gathered fruits,131 movables incorporated into a movable construction so as to become an integral part of it, movables permanently attached to movable constructions, materials gathered for the erection of a new building or other construction (even if derived from the demolition of an old one)132 b) Corporeal movables attached or dedicated to an immovable 1] Other constructions that-a] are not permanently attached to the land and/or b] belong to someone other than the owner CC art. 470. See Yiannopoulos, § 146, at 320-21; see also Cornu, n 912-914, at 295; Terré & Simler, n 26, at 22-23; cf. 1 Steinauer, n 96, at 30; Trabucchi, n 160, at 371. 129 CC art. 470; Yiannopoulos, 146, at 320-21; see also Terré & Simler, n 26, at 22-23. 130 CC art. 471 & comment (c); Yiannopoulos, § 148, at 324-25; see also Malaurie & Aynès, n 110, at 29; 1 Steinauer, n 96, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 17, at 15, & n 28, at 24; cf. Cornu, n 915, at 295-96. 131 CC art. 463 comment (e). 132 CC art. 472; Yiannopoulos, § 148, at 326. 128 -21- C D of the land133 2] Movables that fail to qualify as component parts of a building or other immovable construction because they are not permanently attached thereto either by law or in fact 3] Movables by anticipation: unharvested crops or ungathered fruits that belong to someone other than the owner of the ground134 b Incorporeal movables 1) Definition: Incorporeal movables are rights and actions that apply to movable things.135 2) Illustrations: bonds, annuities, shares of corporate stock, partnership shares, an interest in an employee pension plan, shares of ownership of a movable, right to receive rent (even if the leased thing is itself immovable)136 Nature of criterion of distinction: primarily objective (based on physical characteristics), secondarily 137 subjective (based on declaration of will) Significance. The law (including, but certainly not limited to, just the law of property or even just the civil law) treats immovables and movables differently for a variety of purposes. 1 Property law: Within the law of property, the distinction is important for the following reasons (among others): a Modes of acquiring ownership: 1) Accession: Accession with respect to immovables and accession with respect to movables are governed by radically different regimes.138 Consider, for example, what those regimes CC art. 463; id. art. 464 comment (d). CC arts. 474, 463 & comment (e). See Yiannopoulos, § 115, at 263, & § 128, at 287-89. See also Cornu, 916, at 296; Malaurie & Aynès, n 133, at 40-41; Terré & Simler, n 29, at 25-26. 135 CC art. 473; Yiannopoulos, § 149, at 329; see also Cornu, n 917, at 296-97; Terré & Simler, n 31, at 27-28, 136 CC art. 473; Yiannopoulos, § 149, at 329. 137 See Cornu, nn 921-923, at 298; Malaurie & Aynès, n 110, at 29; Terré & Simler, n 17, at 15; 138 Compare CC arts. 490-506 (immovables) with CC arts. 507-516 (movables). See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236. 133 134 -22- b provide with respect to the ownership of additions to land (called "improvements"), on the one hand, and the ownership of additions to movables (called "accessories"), on the other.139 Who owns an addition to land depends on whether the addition is made with the consent of the landowner: if it is, the addition belongs to him who made it; if it is not, the addition belongs to the landowner.140 An addition to a movable, by contrast, belongs to the owner of that movable.141 2) Acquisitive prescription: Acquisitive prescription of real rights in immovables and acquisitive prescription of real rights in movables are governed by rather different regimes.142 To take just one example, whereas the "delay" required for abridged (good faith) acquisitive prescription for immovables is ten (10) years143, the "delay" required for abridged acquisitive prescription for movables is (3) years.144 Transfer of ownership: effectivity vis-à-vis third persons: publicity:145 Whereas a transfer of the ownership of a movable is made effective as to third persons by the transferor's mere delivery of the thing to the transferee146, a transfer of an immovables is made effective as to third persons only upon the filing into the appropriate public records of the instrument that memorializes the act of transfer (the act of sale, act of donation, etc.)147 Compare CC arts. 493 with CC arts. 508-510. CC art. 493. See Yiannopoulos, § 116, at 265. 141 CC art. 510. 142 Compare CC arts. 3473-3488 with CC arts. 3489-3491. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236. See also Malaurie & Aynès, n 123, at 35; Terré & Simler, n 18, at 16. 143 CC art. 3475. 144 CC art. 3490. 145 CC arts. 517-518 & 2442. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 237-38; see also Cornu, 929, at 200; Malaurie & Aynès, at 33-34; 1 Steinauer, n 97, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 18, at 16; Trimarchi, n 60, at 107; Trabucchi, n 160, at 371. 146 CC art. 518. 147 CC arts. 517 & 2442. 139 140 -23- c 2 148 149 150 Servitudes: domain: Only immovables--corporeal immovables, to be precise--can be subjected to predial servitudes148 and to the personal servitudes of right of use149 and habitation.150 d Accessory real rights: mortgage & pledge (pawn and antichresis): domains:151 With only a handful of exceptions, only immovables can be subjected to mortgages.152 The type of pledge known as "pawn" can be created only on a movable153; the type of pledge known as “antichresis”, only on an 154 immovable. Other: obligations a Formalities 1) Sale. As a general rule the sale of an immovable must be reduced to writing, i.e., in authentic form or by act under private signature.155 The sale of a movable, by contrast, need not be reduced to writing.156 2) Donation inter vivos. Whereas donations inter vivos of immovables must be accompanied by an authentic act157, donations inter vivos of at least some movables, namely, corporeal movables, need not even be accompanied by a writing, in other words, may be accomplished by "manual" gift."158 b Sales: lesion. Whereas the sale of an immovable can be rescinded on grounds of lesion, the sale of a movable cannot.159 CC art. 698 & comments (b) & (c). CC art. 639 & comment (c). CC art. 630 & comment (b). See generally Malaurie & Aynès, n 127, at 38. 151 See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236 & n. 6; see also Cornu, n 929, at 300; Malaurie & Aynès, n 122, at 34-35; 1 Steinauer, n 97, at 30; Terré & Simler, n 18, at 16; Trabucchi, n 160, at 371. 152 CC art. 3286. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236 & n. 6. See also Cornu, n 929, at 300; Malaurie & Aynès, n 122, at 34; Terré & Simler, n 18, at 16. 153 CC arts. 3135, 3154, & 3155. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236 & n. 6. See also Malaurie & Aynès, n 122, at 34-35. 154 CC art. 3135, 3178, & 3179. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236 & n. 6. 155 CC arts. 1839 & 2440. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236 & n. 6. 156 See CC arts. 1839 & 2440. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236 & n. 6. 157 CC art. 1536. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236 & n. 6. 158 CC art. 1539. See Yiannopoulos, § 106, at 236. 159 See CC art. 2589. See Cornu, n 932, at 300; Malaurie & Aynès, n -24- 125, at 36; Terré & Simler, n 18, at 16. -25-