thesis (doc 292 KB) - Australian Centre on Quality of Life

Subjective Wellbeing: An appraisal of the role of HPMood,

Approach-Avoidant Control, Extraversion and Neuroticism.

By

Trish Ayers

B.App.Sc. (Psychology)

B.App.Sc. (Physiotherapy)

B.S.W.

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Bachelor of Applied Science Psychology Honours

School of Psychology, Faculty of Health

Deakin University

24 th

October 2011

Student Number: 700138551

Supervisor:

Campus:

Word Count:

Prof. Robert A. Cummins

Burwood

4997

“I, the undersigned, declare that this Empirical Report is under the specified word limit, and that it comprises original work and writing by me, and that due acknowledgement has been made to all other material used.

Signed Trish Ayers Dated 24/10/11

Deakin University School of Psychology Honours Candidate Certificate

I am the author of the thesis entitled

“Subjective Wellbeing:

Submitted for the degree of Bachelor of Applied Science (Honours) and I agree to grant the Honours Coordinator of the School of Psychology permission to make this thesis available for consultation, loan, or photocopying, in whole or in part.

Signed _________________________ Date: 24/10/11

An appraisal of the role of HPMood,

Approach-Avoidant Control, Extraversion and Neuroticism.”

Deakin University School of Psychology Ethics Summary Statement

Project Number: (ID 2006-266)

Project Title: Subjective Wellbeing: An appraisal of the role of HPMood,

Approach-Avoidant Control, Extraversion and Neuroticism.

.

We the undersigned declare that the above named research project has been completed as described in the Application for Ethics Approval and in accordance with the ethics guidelines of Deakin University.

Researcher’s Name: Ms. Trish Ayers

Researcher’s Signature Date 24/10/11

Supervisor’s Name: Professor Robert Cummins

Supervisor’s Signature ______________________ Date __________________

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1:

Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations for variables Personal

Well Being Index, Approach Control, Global Life Satisfaction, Neuroticism,

Homeostatically Protected Mood, Extraversion and Avoidant

Control……………………………………………………………………………………………………..11

Table 2:

Factor Loading from Principal Components Factor Analysis for Two-factor

Solution for the Approach-Avoidant Dimensions of Control………………………...15

Table 3.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Approach Control and SWB………………………………….…..17

Table 4.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Approach Control and GLS……………………………………….18

Table 5.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Avoidant Control and SWB ……………………………………...19

Table 6.

Table 7.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Avoidant Control and GLS………………………………….….....20

Mediation Analysis Summary for effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Extraversion and SWB…………………………………………......21

Table 8.

Mediation Analysis Summary for effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Extraversion and GLS…………………………………………..…..22

Table 9.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Neuroticism and SWB………………………………………….......23

Table 10.

Mediation Analysis Summary for effect of Mediator HPMood on the

Relationship between Neuroticism and GLS…………………………………………….....24

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.

Unmediated and mediated models, variables including the mediator, are regressed against each other………………………………………………………..……………16

ABSTRACT

This study concerns the composition of Subjective Wellbeing (SWB). While the

Personality factors of Extraversion and Neuroticism have been proposed as the main predictors of SWB, this study investigates whether Homeostatically Protected Mood

(HPMood) is the dominant component of SWB. It also predicts that the relationship between perceived control and SWB will be fully mediated by HPMood. Participants were the first 1000 returned written questionnaire responses from the June 2011, Australian

Research Council (ARC) 21 survey. This survey sampled Australians nationally. Age range of participants was from 21 to 96 years and there were 467 males and 532 females.

Mediation analyses confirmed that HPMood is either a full mediator or a very strong partial mediator of the relationship between Extraversion, Neuroticism, perceived control and two measures of SWB. These results replicate previous research with HPMood emerging as the main constituent of SWB rather than personality. They also extend previous research by demonstrating that HPMood is causal in the relationship between

Approach-Avoidant Control and SWB.

1

SUBJECTIVE WELLBEING

Subjective Wellbeing (SWB) has been described as a reflection of the way people perceive and evaluate life. It encompasses emotional reactions to life events, mood and judgment concerning satisfaction with life domains (Diener, Oishi & Lucas, 2003). SWB has also been described as a product of cognitive evaluations of life experience embedded in an affective background (Davern & Cummins, 2006).

An important characteristic of SWB is the normality of individuals feeling positive about themselves (Cummins, 2010). This positive element of the SWB of Australians has been measured in 24 surveys since 2001 via the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index (AUWI) using the Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI) (International Wellbeing Group, 2006). All results are standardized on a scale of 0 to 100, and the mean scores for SWB is 75 points with a standard deviation of 0.8 points (Cummins, in press). This normally positive value of SWB is associated with a number of psychological mechanisms that operate to hold levels of SWB constant.

SWB homeostasis

One psychological mechanism, proposed as supporting the positive maintenance of

SWB, is homeostasis (Cummins, 2010). In this conception, genetically prewired neurological and psychological processes actively control SWB. These processes are thought to preserve a comprehensive and abstract positive sense of wellbeing, measured by responses to the single question “How satisfied are you with your life as a whole”.

Responses reveal a deep stable positive mood that is the core of SWB (Cummins, in press).

It is proposed that it is this sense of positive mood that homeostasis seeks to preserve.

Set-points

A further psychological mechanism supporting positive SWB is the proposal that each person has a genetically determined SWB set-point and in the absence of significant life events, people tend to maintain a relatively stable level of SWB (Headley & Wearing,

1989).

2

When an individual experiences a major life event their SWB can be temporarily disturbed. According to the Dynamic Equilibrium Model, there is a propensity to regain their previous stable SWB level over time (Headley & Wearing, 1989). The range of setpoints within large normative samples is from 60 – 90 points, having a mean of 75

(Cummins, in press). This SWB homeostatic mechanism aims to keep SWB within each individual’s set-point range and hence poses the question as to the composition of SWB.

3

HPMOOD

There has been significant debate in the literature as to the actual structure of SWB.

The current controversy is the claim by Diener, Scollon, and Lucas (2004) that SWB is mainly a cognitive construct. However, recent research by Blore, Stokes, Mellor, Firth and

Cummins (2011); Davern, Cummins and Stokes (2007), tips the balance towards affect, in the form of a deep stable positive mood, which has been named Homeostatically Protected

Mood (HPMood) by Cummins (2010). HPMood has been described by Cummins (in press) as comprising a blend of hedonic and arousal values. This study will further explore

SWB, by considering the relationship between HPMood, and Perceived Control.

PERCEIVED CONTROL

The literature suggests that successful control in any form is positively related to

SWB (Ferguson & Goodwin, 2010; Heckhausen, Wrosch & Schulz, 2010). Indeed, perceptions of control have been related to positive outcomes such as health, success and adjustment across the lifespan (Skinner, 1996). Perceived control has been categorised as a two-process model (Rothbaum, Weisz & Snyder, 1982).

Two-process model

This two-process model of control comprises primary control, encompassing actions taken to alter the world so that it fits with individual needs. Secondary control is where the individual fits in with the world, employing strategies such as expecting to fail and withdrawing (Rothbaum et al. 1982). Both control processes are intertwined and if these control processes fail, relinquished control when the person feels unable to exert primary or secondary control and gives up, is utilised (Rothbaum et al. 1982).

4

An intertwining of these control processes has been suggested as a means of coping with stressful situations (Cousins, 2002). Perceived control, comprising these connected control processes, may function to impact on individual SWB

Function of perceived control

Perceived control has been proposed as a psychological mechanism supporting the positive maintenance of SWB (Cummins & Nistico, 2002). SWB Homeostasis can be assisted by positive cognitive biases (PCBs) that relate to the self. People attribute success to internal, stable, universal causes and failure to external unstable and particular causes

(Cummins & Nistico, 2002). PCB’s of control thus act as a buffer against adverse psychological effects from hostile events (Cummins & Nistico, 2002) and assists the maintenance of SWB.

A new categorization of perceived control; Approach-Avoidant Control has been developed by Cousins (2002). This categorization is a useful approach representing a more relevant construct than primary and secondary control (Rothbaum et al. 1982) or problememotion-focused coping (Folkman, 1984). The main issue is whether an individual believes that they can address the problem or if they can avoid it (Cousins, 2002).

The rationale for Cousin’s approach was that an exploratory factor analysis concerning perceived control containing the constructs primary, secondary and relinquished control produced a two-factor structure. The first factor, Approach Control reflected items where the problem was addressed. The second factor Avoidant Control, reflected items where the problem was avoided (Cousins, 2002). This factors structure showed no statistical differentiation between primary, secondary and relinquished control items. Indeed, Cousins has refined the composition of perceived control, into clearer dimensions. Consequently, the relationship between Approach-Avoidant Control,

HPMood and SWB is considered.

HPMood, Approach-Avoidant Control and SWB

HPMood has been implicated in recent research as the essence of SWB (Cummins,

2010). Successful control in any form is related to SWB (Heckhausen et al. 2010). This study extends current research by exploring the connection between SWB, Approach-

Avoidant Control and HPMood. This study tests the proposition that HPMood fully mediates the connection between SWB and Approach-Avoidant Control and furthermore considers the literature concerning SWB and personality.

5

PERSONALITY

Personality has been conceptualised as a five-factor model (Costa & McCrae,

1998). Investigation has consistently shown that two-personality factors Extraversion and

Neuroticism are related to SWB. Extraversion, where individuals are sociable, selfconfident warm, optimistic, and exhilaration seeking (Costa &McCrae, 1980), influences

SWB by positive emotion and lowered threshold for activating positive effect (Diener &

Eid, 2006). Secondly, Neuroticism, where individuals have the tendency to experience negative, distressing emotions and posses associated behavior and cognitive traits such as, fearfulness and irritability (Costa & McCrae, 1987) and is inversely related to SWB

( Diener & Ryan, 2009).

Diener has focused on personality as the main predictor of SWB (Diener et al.

2003; Diener, 1984; Diener & Lucas, 1999). However, recent research (Davern et al. 2007,

Blore et al. 2011) has challenged this proposing that the dominant predictor of SWB is

HPMood (Cummins, 2010).

This study further investigates the relationship between Extraversion, Neuroticism,

HPMood and SWB

HYPOTHESES

This study explores the relationship between HPMood, SWB and Approach-

Avoidant Control and investigates whether HPMood fully mediates the relationship. The study also reconsiders the proposition that personality is the main predictor of SWB and proposes instead, that HPMood is the prime constituent of SWB.

The following hypotheses are proposed:-

Hypothesis 1:

That the factorial structure of the Approach-Avoidant Control Scale will be confirmed

The Perceived Control questionnaire (Cousins, 2002) is unique in conceptualising perceived control as either Approach or Avoidant. However, the structure of the scale rests on a single study. This will be tested using the same items identified by Cousins (2002) and an additional experimentally introduced item. An exploratory factor analysis will determine whether the two factors found by Cousins can be replicated.

6

Hypothesis 2:

The relationship between both Approach-Avoidant Control and SWB be fully mediated by HPMood

The literature suggests that successful control in any form is positively related to

SWB (Ferguson & Goodwin, 2010; Heckhausen et al. 2010). Perceived control has been found to operate as a PCB in maintaining SWB (Cummins & Nistaco, 2002). HPMood has been proposed as the dominant constituent of SWB (Cummins, 2010). This study proposes that HPMood fully mediates the relationship between Approach-Avoidant Control and

SWB.

Hypothesis 3:

The relationship between Extraversion-Neuroticism and SWB will be fully mediated by HPMood.

There is extensive literature positively relating trait Extraversion and negatively relating trait Neuroticism to SWB (Costa & McCrae, 1980, Diener, 1996). These findings, however, do not account for mood as a contributing factor. Recent research by Blore et al.

(2011), Davern et al. (2007) has found that HPMood mediates the relationships between

Extraversion-Neuroticism and SWB. This study tests whether HPMood fully mediates the relationship between Extraversion-Neuroticism and SWB.

METHOD

Participants

The data used for the analysis came from the AUWI. This project comprises an ongoing research program measuring the subjective wellbeing of Australians through a partnership between Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University, and

Australian Unity.

This survey consisted of 2,198 Australians representative of the adult population aged 18 and over. Participants were originally randomly selected from telephone numbers within geographical areas representative of population distribution. On completion of telephone interviews, these participants had consented to joining the ongoing longitudinal wellbeing research project for periodical survey via written questionnaires. The sample for this study comprised the ARC21 st survey conducted in June 2011. The first 1000 responses were included. There were 467 male and 532 females age range 21 to 96 years, mean of

59.98 ( SD = 14.57). Refer to demographic information (Appendix A, Table A1). The overall response was 62.6%.

7

Materials

Subjective Wellbeing

The AUWI included two measures of SWB. The first is the global evaluation of life satisfaction, (GLS), “How satisfied are you with your life as a whole”. (Appendix B, B1, item 1). This item is rated on an 11-point scale ranging from (0), no satisfaction at all, to

(10), completely satisfied. This item was selected on the basis of an earlier study

(Cummins, Eckersley, Pallant, Van Vugt & Misajon, 2003), which suggested that the mood core of SWB is reflected most accurately by an abstract question around personal satisfaction.

Another measure of SWB the PWI (Appendix B, B1, items 2-9), assessed SWB using the aggregate of seven domains of satisfaction. The mean of these domains comprises a measure of SWB. Participants responded indicating level of satisfaction on an

11-point-scale from (0) no satisfaction at all to (10), completely satisfied. The scale has

high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha between .70 and .85 (International

Wellbeing Group, 2006). The test-retest reliability over a one to two-week period has demonstrated an intra-class correlation coefficient of .84 (Cummins & Lau, 2005).

Cronbach’s alpha for the PWI for the current study was .86.

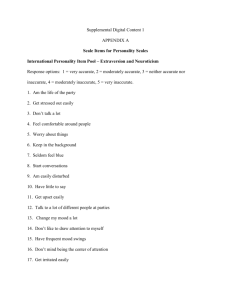

Personality

The personality dimensions Extraversion and Neuroticism utilised in this study were measured using 24 items; 12 measuring each dimension. Items were taken from the

NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) (Costa & McCrae, 1992) (Appendix B, B1, items

68–91). These two personality dimensions are the most strongly related to SWB (Davern,

2004). Participants responded indicating level of agreement on an 11point scale from (0), do not agree at all, to (10) agree completely. The NEO-FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1992) was designed as a brief form of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory . The NEO-FFI has an estimated adequate test-retest reliability over 12 weeks, N = .79, E = .79. (N = 208), p <.

001 (Costa & McCrae, 1992). In the current sample Cronbach’s alpha for Extraversion and

Neuroticism were .81 and .87 respectively.

8

Approach-Avoidant Control

A Coping with Life Scale containing 12 items was used to measure the concept of

Approach-Avoidant Control. (Appendix B, B1, items 48 – 59). Eleven of these items were derived from a Perceived Control Questionnaire, which conceptualised control as

Approach or Avoidant (Cousins, 2002). Six items, which had the strongest loading on the

Approach factor, were selected. Only five items loaded on to the Avoidant factor, all were selected. An additional item was sourced from the Coping Response Inventory (Moos,

1993) to have equal number of questions representing each dimension. Participants responded indicating level of agreement on an 11-point scale from (0), do not agree at all to (10), completely agree. This new scale requires replication. Cronbach’s alpha for

Approach-Avoidant Control in this study was .87 and .76 respectively.

HPMood

The scale to measure HPMood comprised three items (Appendix B, B1, items 4,

19, 36). These items were selected as suggested by Cummins (2010). The instructions for

answering the items on the HPMood scale used in this study were: “Thinking about my life in general I feel”… Responses measuring HPMood included, alert, happy, contented.

9

Participants responded on an 11-point scale indicating level of agreement from (0), do not agree at all to (10), completely agree. Cronbach’s alpha was .82 in this study.

Procedure

Ethics approval was gained from Deakin University Human Research Ethics

Committee (Appendix C, C1) Potential respondents received a package containing a covering letter (Appendix C, C2) a plain language statement, (Appendix C, C3) the ARC

21 questionnaire (Appendix B, B1), demographic information sheet (Appendix B, B2) and a reply paid envelope. These packages were mailed to participants from a private company

(Salmat) where participant information is confidentially stored. Completed questionnaires were returned to Deakin University. Information from the questionnaires was professionally transcribed, observing participant confidentially.

RESULTS

Preliminary data analysis

All analyses in this study were performed using SPSS version18.0. Means, standard deviations and response scores have been converted to a standard 0-100 scale. When a score is rated on a 0 to 10 scale, the conversion is calculated through the formula x = score to be converted, multiplied by 100 and divided by the number of scale points minus 1

(Cummins, 1995). The conversion assists the reader to understand scores and comparisons with other data. The PWI variable showed a number of participants scoring 100. These results were deleted to avoid the inclusion of socially acquiescent responses.

All assumptions of parametric statistics were met. The sample size of 1000 was greater than the criterion of a minimum of 5 respondents per variable outlined by

Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). A missing data analysis showed that all variables, except

Extraversion, Neuroticism and HPMood, had less than 5% missing cases. Missing data were not replaced, rather all cases were retained and cases were excluded pairwise from the analysis. This way of managing missing data is strongly recommended by Pallant

(2011).

Outliers were determined as values further than 3.3 standard deviations from the

1

0 mean. Neuroticism was the only variable showing outliers, containing three, uni-variate outliers. There were no multivariate outliers. Analyses run with and without these three outliers found negligible differences in degree of variance, so sample integrity was maintained and outliers retained.

Descriptives

Descriptive information, including means, standard deviations and bi-variate correlations for each of the variables, were calculated. These are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 :

Means (M), standard deviations (SD) and bivariate correlations for variables Personal Well Being Index (PWI), Approach Control,

Global Life Satisfaction (GLS), Neuroticism, Homeostatically Protected Mood (HPMood), Extraversion and Avoidant Control, N=1000.

SWB Approach GLS Neuroticism. HPMood Extraversion. Avoidant

SWB

Approach

GLS

Neuroticism

HPMood

Extraversion

Avoidant

M 74.75

SD 14.17

.40**

70.49

15.94

**Correlations significant at p < 0.01 levels, (2-tailed)

.77**

.32**

75.69

17.19

-.46**

-.34**

-.43**

35.30

17.44

.76**

.52**

.76**

-.51**

71.90

17.47

.43**

.39**

.37**

-.39**

.50**

57.41

13.36

.09**

.14**

.10**

.06

.14**

.06

44.81

19.15

1

1

1

2

The individual mean scores for SWB and GLS in the current sample closely approximate the group mean scores of 75.17 which has been measured by the PWI in a combined data set from 24 independent Australian surveys, conducted between 2001 to

2010, (Cummins, in press). Interestingly HPMood has a mean of 71.90, which is relatively close to the mean measures of SWB and GLS.

Factor Analysis

PWI

A principal components (PCA) analysis was undertaken to confirm the factor structure of the PWI (Appendix D, Table D1). Data were suitable for factor analysis as all coefficients from the correlation matrix were .3 and above (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) = .88, exceeding the minimum value of .6 (Kaiser, 1974) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance (Bartlett, 1954), supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. Analysis, with direct Oblimin rotation with

Kaiser Normalisation, revealed the emergence of one factor explaining 55.62% of the variance.

Extraversion-Neuroticism

The combined Extraversion and Neuroticism scores were subjected to PCA. Prior to performing the PCA it was determined that many coefficients were .3 and above. The

KMO = .91 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity reached statistical significance supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. There were 24 items in the analysis, 12 representing

Extraversion and 12 representing Neuroticism.

A forced two-factor solution showed that one item from the Neuroticism scale, “I rarely feel lonely”, had to be removed as it loaded equally on to both of the factors. A second analysis with this item omitted, revealed two clean factors, Neuroticism accounting for 29.15% and Extraversion, explaining 12.60% of the variance; total variance explained

41.75% (Appendix D, Table D2). The factors are weakly negatively correlated, r = -.312.

1

3

HPMood

Data were suitable for factor analysis as all coefficients from the correlation matrix were above .5. The KMO = .68 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. Analysis revealed the emergence of one component accounting for 74.66% of the variance (Appendix D, Table

D3).

Hypothesis 1:

That the factorial structure of the Approach-Avoidant Control scale will be confirmed

To confirm the factorial structure of the Approach-Avoidant Control scale Cousins,

(2002) the 12 items of the scale were subjected to a (PCA). Inspection of the correlation matrix revealed the presence of many coefficients of .3 and above indicating suitability for

PCA. The KMO = .85 exceeding the recommended value of .6 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity reached statistical significance supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix.

PCA revealed the presence of three components with eigenvectors exceeding 1, explaining 31.93%, 20.90%, and 8.67% of the variance respectively. An inspection of the scree plot revealed a clear break after the second component. There were only two items in the third component, items 54 and 59 (See Appendix B, B1). Item 59 was the experimentally added item. It was decided to delete it in order to improve a two-factor solution. Item 54, loaded moderately on to component 2, at .69 and weakly on to component 3, at .35.

A further PCA was run with item 59 deleted and a two-factor solution was revealed explaining 34.58% and 22.39% of variance respectively. The results showed the components were independent ( r = .11). To aid in the interpretation of these two components, an Oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalisation was performed. The rotated solution revealed the presence of a simple structure, with both components showing a number of strong loadings and all items now loading substantially on to only one the two components. The internal consistency was high for Component 1, Approach Control (

α=.

87). Internal consistency was moderate for Component 2, Avoidant Control (α

=.

76). The

interpretation of the two components was consistent with previous research by Cousins,

(2002). Items measuring Approach Control loading strongly onto component 1 and items

1

4 measuring Avoidant Control loading strongly onto component 2. The results of this analysis support the use of Approach and Avoidant components as separate scales. Results of the factor analysis are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2:

Factor Loading from Principal Components Factor Analysis for Two-factor Solution for

the Approach-Avoidant Dimensions of Control

1

5

50.

51.

48.

56.

53.

58.

55.

52.

Questionnaire Items

I look for different ways to achieve the goal

I put lots of time into overcoming it

I work hard to overcome it

I learn the skills to overcome it

I work out what caused it

I make an effort to make good things happen

I tell myself it doesn’t matter

I relax and don’t think about it

54.

I realise I didn’t need to control it anyway

49.

I ignore it by thinking about other things

57 . I don’t feel disappointed because I knew it might happen

Correlation between each factor

Percent of variance explained

Cronbach’s Alpha

Approach

Control

(N = 950)

.830

Avoidant

Control

(N = 948)

.798

.774

.749

.748

.743

.802

.794

.675

.653

.618

.11

34.58

. 87

22.39

.76

1

6

Statistical analyses for hypotheses 2 and 3

For testing Hypothesis 2 and 3, a mediation analysis has been used. Following

Baron and Kenny’s (1986) guidelines, four steps were tested using multiple regression equations:

Steps 1, 2 and 3 regressed each variable against one another to establish a significant association. These are X - Y path c (unmediated model), X – M path a, and M -

Y path b, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 . Unmediated and mediated models, variables including the mediator, are regressed against each other.

X c Y

(Kenny, 2011)

Step 4 tests for mediation (path c') as shown in figure 1, by regressing X on Y after controlling for the mediator M. Full mediation occurs when variable X no longer affects Y so path c’ is zero. Partial mediation is determined when the path from X to Y is significantly reduced.

Hypothesis 2:

The relationship between Approach-Avoidant Control with SWB will be fully mediated by

HPMood

Separate mediation analyses were conducted for both dimensions of control comprising SWB and GLS.

Mediation 1. Approach Control, HPMood and SWB. This tested whether HPMood mediated the relationship between Approach Control and SWB. The results are shown in

Table 3.

1

7

Table 3.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship

between Approach Control and SWB

B SE B

β

Testing Step 1 path c

SWB

Predictor Approach Control .355

R2

.027

=. 159 Adj.

.399**

R2 =. 158

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Approach Control .570 .031

R2 =. 270

.520**

Adj. R2 =. 269

Testing Step 3& 4, path b and c’

SWB

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

.618 .021 . 762**

.003

R2

.023

=. 583

.003

Adj. R2 =. 582

** p < .001

These results indicated that Approach Control and SWB were fully mediated by

HPMood, Sobel’s test (Z = 15.59, p < 0.000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 15.9% to 58.3%. HPMood accounted for 42.4% of the variance in SWB above and beyond that accounted for by Approach Control. When

HPMood was introduced into the mediation, it totally saturated the predictive relationship between Approach Control and scores on SWB.

Mediation 2. Approach Control, HPMood and GLS. This tested whether HPMood mediated the relationship between Approach Control and GLS. The results are shown in

Table 4.

1

8

Table 4.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship between Approach Control and GLS

B SE B

β

Testing Step 1 path c

GLS

Predictor Approach Control .345

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Approach Control .570

Testing Step 3 & 4 path b and c’

GLS

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

.796

-.108

.033

R2

R2

=. 103

.031

=. 270

.025

.028

R2 = .580

.320**

Adj. R2

.520*

Adj. R2

=. 102

=. 269

.809**

-.100**

Adj. R2 =. 579

** p < .001

Results indicated that Approach Control and GLS were partially mediated by

HPMood, Sobel’s test (Z = 15.59, p < 0.000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 10.3% to 58.0%. HPMood accounted for 47.7% of the variance in GLS above and beyond that accounted for by Approach Control. When

HPMood was introduced into the mediation, the predictive relationship of Approach

Control on scores of GLS was weakened.

Mediation 3. Avoidant Control, HPMood and SWB. This tested whether HPMood mediated the relationship between Avoidant Control and SWB. The results are shown in

Table 5.

Table 5.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship between Avoidant Control and SWB

B SE B

β

Testing Step 1 path c

SWB

Predictor Avoidant Control

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Avoidant Control

Testing Step 3 & 4 path b and c’

SWB

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

.069

.129

.621

-.011

.024

R2 =. 009

.018

.016

.093*

Adj. R2 =. 008

.030 .141**

R2 = .020

Adj. R2 =. 019

.766**

-.015

R2 =. 583 Adj. R2 =. 582

* p < .01, ** p < .001.

Results indicated that Avoidant Control and SWB were fully mediated by

HPMood, Sobel’s test (Z =4.27, p < .000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 0.9% to 58.3%. HPMood accounted for 57.4% of the variance in SWB above and beyond that accounted for by Avoidant Control. When

HPMood was introduced into the mediation, it totally saturated the predictive relationship between Avoidant Control and scores on SWB.

Mediation 4. Avoidant Control, HPMood and GLS. This tested whether HPMood mediated the relationship between Avoidant Control and GLS. The results are shown in

Table 6.

1

9

2

0

Table 6.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship between Avoidant Control and GLS.

B SE B

β

Testing Step 1 path c

GLS

Predictor Avoidant Control

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Avoidant Control

Testing Step 3 & 4 path b and c’

GLS

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

.091

.129

.746

-.005

.029 .101*

R2 =. 010 Adj. R2 =. 009

.030

R2 = .020

.141**

Adj. R2 =. 019

.022

.020

.758**

-.006

R2 =. 573 Adj. R2 =. 572

* p < .01, ** p < .001.

Results indicated that Avoidant Control and GLS were fully mediated by HPMood,

Sobel’s test (Z = 4.27, p < .000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 1.0% to 57.3%. HPMood accounted for 56.3% of the variance in

GLS above and beyond that accounted for by Avoidant Control. When HPMood was introduced into the mediation equation, it totally saturated the predictive relationship between Avoidant Control and scores on GLS.

Hypothesis 3:

The relationship between Extraversion, Neuroticism, and SWB will be fully mediated by

HPMood.

Separate mediation analyses were conducted for both dimensions of personality,

Extraversion and Neuroticism, each comprising SWB and GLS.

Mediation 5. Extraversion, HPMood and SWB. This tested whether HPMood

2

1 mediated the relationship between Extraversion and SWB. The results are shown in

Table 7.

Table 7.

Mediation Analysis Summary for effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship

between Extraversion and SWB.

B SE B β

Testing Step 1 path c

SWB

Predictor Extraversion

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Extraversion

Testing Step 3 & 4 path b and c’

SWB

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

.453

.657

.596

.062

.034 .427**

R2 =. 183 Adj. R2 =. 182

.041 .503**

R2 =. 253 Adj. R2 =. 252

.022

.029

.734**

.058*

R2 =. 586 Adj. R2 =. 585

** p < .001, * p <.05

Results indicated that Extraversion and SWB were partially mediated by HPMood,

Sobel’s test (Z = 13.79, p < 0.000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 18.3% to 58.6%. HPMood accounted for 40.3% of the variance in

SWB above and beyond that accounted for by Extraversion. When HPMood was introduced into the mediation equation, the predictive ability of Extraversion on scores of

SWB was weakened.

Mediation 6. Extraversion, HPMood and GLS. This tested whether HPMood mediated the relationship between Extraversion and GLS. The results are shown in Table

8.

Table 8.

Mediation Analysis Summary for effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship

between Extraversion and GLS

B SE B β

Testing Step 1 path c

GLS

Predictor Extraversion

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Extraversion

Testing Step 3 path b and c’

GLS

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

.472

.657

.754

-.024

R2 =. 134

R2 =. 253

R2

.042

.041

.027

.035

=. 573 Adj. R2

.367**

Adj. R2 =. 133

.503**

Adj. R2 =. 252

.766**

-.019

=. 572

** p < .001

Results indicated that Extraversion and GLS were fully mediated by HPMood,

Sobel’s test (Z = 13.90, p < 0.000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 13.4% to 57.3%. HPMood accounted for 43.9% of the variance in GLS above and beyond that accounted for by Extraversion. When HPMood was introduced into the mediation equation, it totally saturated the predictive relationship between Extraversion and scores on GLS.

Mediation 7. Neuroticism, HPMood and SWB. This tested whether HPMood mediated the relationship between Neuroticism and SWB. The results are shown in

Table 9.

2

2

2

3

Table 9.

Mediation Analysis Summary for the effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship

between Neuroticism and SWB

B SE B

β

Testing Step 1 path c

SWB

Predictor Neuroticism

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Neuroticism

Testing Step 3 path b and c’

SWB

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

-.374

-.508

.579

-.080

.021

.021

.025 -.460**

R2 =. 212 Adj. R2 =. 211

.030 -.507**

R2 =. 257 Adj. R2 =. 256

.714**

-.099**

R2 =. 590 Adj. R2 =. 589

** p < .001

Results indicated that Neuroticism and SWBs were partially mediated by HPMood,

Sobel’s test (Z = -14.43, p < 0.000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 21.2% to 59.0%. HPMood accounted for 37.8% of the variance in SWB above and beyond that accounted for by Neuroticism. When HPMood was introduced into the mediation it weakened the predictive ability of Neuroticism on scores of SWB.

Mediation 8. Neuroticism, HPMood and GLS. This tested whether HPMood mediated the relationship between Neuroticism and GLS. The results are shown in

Table 10.

2

4

Table 10.

Mediation Analysis Summary for effect of Mediator HPMood on the Relationship

between Neuroticism and GLS

B SE B

β

Testing Step 1 path c

GLS

Predictor Neuroticism -.424 .030

R2 =. 185

-.431**

Adj. R2 =. 184

Testing Step 2 path a

HPMood

Predictor Neuroticism

Testing Step 3 path b and c’

-.508

R2

.030

=. 257

-.507**

Adj. R2 =. 256

GLS

Mediator HPMood (b)

Mediation (c’)

.713

-.062

R2

.026

.026

=. 576

.725**

-.063*

Adj. R2 =. 575

** p < .001, * p < .05.

Results indicated that Neuroticism and GLS were partially mediated by HPMood,

Sobel’s test (Z = -14.41, p < 0.000). The amount of variance accounted for by the mediation model increased from 18.5% to 57.6%. HPMood accounted for 39.1% of the variance in GLS above and beyond that accounted for by Neuroticism. When HPMood was introduced into the mediation it weakened the predictive ability of Neuroticism on scores of GLS.

2

5

DISCUSSION

Prior to hypothesis testing, the factorial structure of a new scale, the Approach-

Avoidant Control scale, was examined.

This scale was then used in a mediation analysis to investigate whether; HPMood fully mediates the relationship between Approach-Avoidant dimensions of control and two measures of SWB. Furthermore, this study considers via an additional mediation analysis, whether HPMood fully mediates the relationship between personality factors Extraversion and Neuroticism and two measure of SWB.

Approach-Avoidant Scale

The first hypothesis was confirmed with the dimensions Approach-Avoidant

Control emerging as two clear factors. This occurred after deletion of an additional item, which had been experimentally added to the original Cousins (2002) scale. Whereas items loading on the Approach scale described an active attempt to cope, in contrast, items loading on to the Avoidant scale involved passive acceptance, however, the additional item described an active attempt to avoid the problem. It therefore did not fit into Cousins

Approach-Avoidant factor structure. The Cronbach’s alpha of .87 Approach Control and

.76 Avoidant Control confirmed the reliability of these two scales.

Approach-Avoidant Control and SWB

The second hypothesis was generally supported. Full mediation occurred between both forms of control & SWB, and between Avoidant control and GLS. Very strong partial mediation was found between Approach Control and GLS.

This finding indicated that the shared variance between SWB and Approach-

Avoidant dimensions of control was comprised of HPMood. Approach-Avoidant Control systems could be viewed as adhering to basic properties of self-regulation, that is, the tendency to approach desired objects and situations and the tendency to avoid dangerous objects and situations (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Hence it is possible that, as

HPMood has been considered as perfusing all abstract cognitive processes (Cummins,

2010), and HPMood generally fully mediates the relationship between Approach-Avoidant

Control and SWB, HPMood could also perfuse Approach-Avoidant Control responses.

This proposal adds an additional perspective to the work of (Cummins & Nistico,

2

6

2002), which ascertains that perceived control acts as PCBs in the maintenance of SWB. In the current study perceived control has been conceptualised as Approach-Avoidant dimensions of control. Findings that the relationship between Approach Control and SWB measured by the PWI, and Avoidant Control and both measures of SWB, were fully mediated by HPMood, could imply that Approach Control could be deemed to have only a very minor independent contribution to SWB, and Avoidant Control, no independent contribution to SWB. This finding could imply that PCBs of control, that have been thought to be a buffer against adverse psychological affects from hostile events, are under the direct influence of HPMood. These findings highlight the major contribution of

HPMood to SWB and concur with recent findings implicating HPMood as a major constituent of SWB (Blore et al. 2011; Cummins, 2010; Davern et al. 2007)

Extraversion-Neuroticism and SWB

The third hypothesis was partially supported. Full mediation occurred between

Extraversion and GLS. However very strong partial mediation also occurred between

Extraversion and the PWI measure of SWB and Neuroticism and both measures of SWB.

Neuroticism and Extraversion have been related to two elements of SWB, negative and positive affect (Steel, Schmidt & Shultz, 2008). The findings in this study are contrary to the view that personality is a major determinant of SWB (Diener & Eid,

2006; Diener et al. 1999; Diener, 1984) and support the findings from recent research implicating HPMood as the dominant predictor of SWB (Davern, 2004; Davern et al.

2007, Blore et al. 2011; Cummins, 2010).

Extraversion has been related to SWB through the feeling of positive emotions and having a lower threshold for activating positive affect (Diener & Eid, 2006). It is interesting that Extraversion still had a minor independent contribution to SWB. The PWI contains a cognitive evaluation in relationship to individuals’ assessment of life domains, whereas GLS is a more affective construct. Considering both the contribution of

Extraversion and HPMood to SWB, it could be that this contribution of Extraversion is emanating from the effect of the perfusion of personality by HPMood (Cummins, 20101), so that the effect of Extraversion is actually an effect of HPMood.

The relationship between both measures of SWB and Neuroticism were very strongly partially mediated by HPMood. Just as HPMood perfuses personality (Cummins,

2

7

2010) via Extraversion, so it also perfuses Neuroticism. The current sample experiences a low level of Neuroticism and thus it makes sense that HPMood as a positive construct laced with happiness, contentment and alertness, will decrease the predictive inverse relationship between Neuroticism and SWB when it is entered onto the mediation equation. It would be interesting to observe the effects of HPMood in a sample where

Neuroticism levels are high.

Limitations

Of the major limitations in this study, was the possibility of other mediators impacting the relationship between the mediator HPMood and the outcome SWB. This limitation could be addressed using the entire sample, applying structural equation modeling and inserting any further variables of interest into the equation.

Future research

The sample in this study was the first 1000 respondents, mean age of 60. Further research could run these analyses with the entire sample and compare findings throughout the lifespan.

Conclusion

The factor structure of the new Approach-Avoidant Control scale was confirmed.

The mediating role of HPMood in relation to the Approach-Avoidant Control Scale and

Extraversion-Neuroticism and SWB was confirmed, with HPMood accounting for a large proportion of the variance in SWB in all mediations. These findings are contrary to the view that personality is an important contributor to SWB; indeed these findings endorse

HPMood as the preferred major contributor to SWB.

2

8

REFERENCES

Baron, R. M., Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 , 1173-1182.

Bartlett, M.S. (1954). A Note on the Multiplying Factors for Various χ2 Approximations.

Journal of Royal Statistical Society 16, (2), 296-298.

Blore, J. D., Stokes, M. A., Mellor, D. A., Firth, L., Cummins, R. A. (2011). Comparing

Multiple Discrepancies Theory to Affective Models of Subjective Wellbeing,

Social Indicators Research, 100 , 1-16.

Carver, C.S., Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and Coping. Annual review of

Psychology, 61 , 679-704.

Costa, P. T., Jr., McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of Extroversion and Neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 38, 668-678.

Costa, P. T., Jr., McCrae, R. R. (1987). Neuroticism, Somatic Complaints, and Disease: Is the Bark Worse than the Bite? Journal of Personality, 55, 299-316.

Costa, P.T., Jr., McCrae, R.R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and

NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) manual.

Odessa, FL: Psychological

Assessment Resources.

Costa, P.T., McCrae, R.R. (1998). The Five-factor theory of personality in Handbook of personality: theory and research

O. John, R Robins & L. Pervin (pp159-181) New

York: Guildford Press.

Cousins, R. (2002). Predicting subjective quality of life: The contributions of personality and perceived control. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Deakin University, Melbourne,

Australia.

Cummins, R. A. (1995). On the trail of the gold standard for subjective well-being. Social

Indicators Research, 35, 179-200.

2

9

Cummins, R. A. (2010). Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: A synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 1-17.

Cummins, R. A. (in press 2012). Positive Psychology and Subjective Wellbeing

Homeostasis: A critical examination of congruence. In D. Moraitou, & A. Efklides

(Eds.), Quality of Life: A Positive Psychology Perspective.

New York: Springer.

Cummins, R.A. & Lau, A.L.D. (2005). Quality of life measurement. In: R. Norman & D.

Currow (Eds.), Supportive care of the urology patient (pp. 5-23). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Cummins, R.A., Nistico, H. (2002). Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. Journal of Happiness Studies , 3 , 37-69.

Cummins, R.A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., Van Vugt, J., Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index. Social

Indicators Research , 64 , 159-190.

Davern, M. (2004). Subjective well-being as an affective construct. Unpublished Doctoral

Thesis. School of Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia.

Davern, M. T., Cummins, R. A. (2006). Is life dissatisfaction the opposite of life satisfaction? Journal of Psychology , 58 , 1-7.

Davern, M. T., Cummins, R. A., Stokes, M. (2007). Subjective wellbeing as an affectivecognitive construct. Journal of Happiness Studies , 8 , 429-449. doi: 10.1007/s10902-

007-9066

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575 .

Diener, E. (1996). Traits are powerful, but are not enough: Lessons from subjective wellbeing . Journal of Research in Personality , 30 , 389-399.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well- being:

Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54 , 403-

426.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (1999). Personality and subjective wellbeing. In D. Kahneman,

E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic

3

0 psychology, (pp. 213-229). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well- being:

Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54 , 403-

426.

Diener, E., Ryan, K., (2009). Subjective well-being a general overview.

South African

Journal of Psychology, 39(4), pp. 391-406.

Diener, E., Scollon, C N., Lucas, R. E. (2004). The evolving concept of subjective well- being: The multifaceted nature of happiness. Advances in Cell Aging and

Gerontology, 15 , 187–219.

Eid, & E. Diener (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of multi-method measurement in psychology,

(pp. 457–463). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ferguson, S. J., Goodwin, A. D. (2010). Optimism and well-being in older adults: The mediating role of social support and perceived control. International Journal of

Aging and Human Development , 71 , 43-68.

Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 839-852.

Headley, B., Wearing, A. (1989). Personality, life events, and subjective well-being:

Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology , 57 , 731-739.

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., Schulz, R. (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review, 117 , 32-60.

International Wellbeing Group. (2006). Personal Wellbeing Index Manual ., Melbourne:

Deakin University. Retrieved from http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/wellbeing-index/pwi-aenglish.pdf

Kaiser, H. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika , 39, 31-6.

Kenny, D.A. (2011). Mediation. Retrieved from http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm

Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual, A step by step guide to data analysis using the

SPSS program 4 th Edition, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Snyder, S. (1982). Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 42, 5-37.

Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 71 , 549-570.

Steel P, Schmidt J, Shultz J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin , 134 , 138–61.

Tabachnick B., Fidell L. S. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics 5th edn Boston:

Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

3

1

APPENDICIES

3

2

Appendix A Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Table A 1

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N =999)

Gender

Male

Female

Age

20-29 years

30-39 years

40-49 years

50-59 years

60-69 years

70-79 years

80-89 years

90-99 years

Location

Northern Territory

New South Wales

Victoria

Queensland

South Australia

Western Australia

Tasmania

Who lives with you

Live alone

Live with partner

Live with one or more children

Live with one or both parents

Live with 1 or more adults not partner /parent

25

67

149

219

263

184

88

4

N

467

532

220

680

295

29

64

191

87

105

29

12

323

250

%

46.7

53.2

2.5

6.7

14.9

21.9

26.3

18.4

8.8

0.4

22

68

29.5

2.9

6.4

1.2

32.3

25

19.1

8.7

10.5

29.5

3

3

Married

Separated

Divorced

Widowed

Full time work status

Full time paid employment

Full time retired

Semi-retired

Full time volunteer

Full time home or family care

Full time study

Unemployed

Part time work

Part time volunteer

Part time volunteer

Part time volunteer

Part time study

Part time study

Casually employed

Casually employed

Annual Gross Income

Less than 15,000

15,000 – 30,000

31,000-60,000 -

61,000-100,000

101,000-150,000

151,000--250,000

251,000-500,000

More than 500,000

1.1

2.8

16.6

21.1

4.1

6.8

7.2

22.5

22.0

20.4

15.4

7.3

0.7

0.3

29.4

39.5

93

.2

6.4

%

62.6

2.6

8.5

10.3

3

4

211

41

11

28

166

68

204

154

73

7

3

72

225

220

294

395

93

2

64

N

626

26

85

103

Appendix B ARC21 and Demographics

B 1. Australian Research Council21, Questionnaire for participants comprising items

1 to 95. Refer attachment 1

B 2. Demographic questionnaire for participants. Refer attachment 2

3

5

Appendix C Ethics and participants documents

C 1. Ethics Approval Deakin University Ethics Committee. Refer attachment 3

C 2. Covering letter for respondents. Refer attachment 4

C 3. Plain language statement. Refer attachment 5

3

6

3

7

Appendix D Factor Analysis

Table D 1

Factor Loading from Principal Components Factor Analysis for the PWI measure of SWB

(N = 962)

Questionnaire Items PWI

4.

Achievements in life

8.

Future security

2.

Standard of living

6.

How safe you feel

5.

Personal relationships

7.

Part of community

3.

Health

Percent of variance explained

Cronbach’s Alpha

.813

.800

.794

.730

.712

.698

.659

55.62

. 86

3

8

Table D 2

Factor Loading from Principal Components Factor Analysis for Two-factor solution for

the Extraversion Neuroticism Dimensions of Personality

Questionnaire Items Neuroticism

(N = 885)

Extraversion

(N = 817)

76.

I often feel tense or jittery .762

72.

When I am under a great deal of stress sometimes I feel like I am going to pieces

.738

78.

84.

70.

Sometimes I feel completely worthless

I often get discouraged and feel like giving up

I often feel inferior to others

88.

I often feel helpless and want someone else to solve my problems

.717

.713

.696

.689

68.

I am a worrier

90.

At times I have been so ashamed that I just wanted to hide

.661

.645

82.

I often get angry at the way people treat me

80.

I rarely feel fearful or anxious (Rffi13 ANX)

86 . I am seldom sad or depressed (Rffi19DEP)

83.

I am a cheerful high-spirited person

77.

I like to be where the action is

69.

I like to have a lot of people around me

75.

I really enjoy talking to people

81.

I often feel as if I’m bursting with energy

85.

87.

I am a cheerful optimist

My life is fast-paced

I laugh easily

.625

.515

.365

-.359

.649

.642

.615

.605

.734

.711

.691

.574

Questionnaire Items

73.

I am very light-hearted

89.

I am a very active person

Correlation between each factor

Percent of variance explained

Cronbach’s Alpha

Neuroticism

(N = 885)

Extraversion

(N = 817)

.556

.528

3

9

-.321

29.15

.87

12.60

.81

Table D 3

Factor Loading from Principal Components Factor Analysis for the HPMood measure (N

= 923)

4

0

Questionnaire Items HPMood

36.

Thinking about my life in general I feel contented

.899

.898

.791

19.

Thinking about my life in general I feel happy

40.

Thinking about my life in general I feel alert

Percent of variance explained

Cronbach’s Alpha

74.66

.82