Notes: Investment and Inventories - The University of Chicago Booth

advertisement

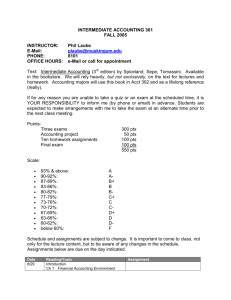

NOTES 5: Investment and Inventories These notes will be short – although, the information provided is quite powerful and will be a major component of the rest of the class. These notes discuss the relationship between interest rates (r) and investment decisions (I). Additionally, for those interested in forecasting future economic conditions, I will outline the predictive power of inventory changes. A few things before we begin: 1) Remember, investment (I) in this class refers to the purchasing of plant facilities and equipment by firms. These resources are used as an input in production. I is a flow variable (which just means it is measured over time). 2) Capital (K), often indexed Kt , t = 0… ∞, is the capital stock in our production equation. K is a stock variable (which means it is measured at a specific point). Formally, K is the sum of all past investment decisions (less any depreciation). The capital stock next period is a function of how much we invest this period. If we invest more today, the capital stock tomorrow will be higher. As an identity: Kt+1 = (1-δ) Kt + I, where Kt+1 is the capital stock next period, Kt is the capital stock today, and δ is the depreciation rate on existing capital. Sometimes, I will write the equation as such: Kf = (1-δ) K + I , where Kf is the future (f) capital stock. I am going to use Kf and Kt+1 interchangeably. Any time a variable has a superscript of (f) implies it is the future value of the variable. The equations tell us that investing today increases the capital stock tomorrow. In other words, if you plan to buy a new machine today, it will be productive for you tomorrow. There is a delay because it takes time to build a new plant, install a new machine, or train workers to use the machine. As a simplification, we will often assume that changing I today does not affect Y* today (hence, K today must not of changed). This is another reason why I assume that changing investment today does not affect the capital stock today. This assumption will make our graphing easier! How much capital (K) should a firm have? 1 In this class, we assume firms optimize. That is, they are going to set the benefit of purchasing capital equal to the cost of purchasing capital. What is the benefit of purchasing capital? The extra benefit associated with one more unit of capital is the marginal product of capital (MPK). From Topic 2 slides, we have the identity for MPK: MPK = 0.3 A (N/K) 0.7 Recall, we derived this identity by taking the partial derivative of our Cobb-Douglas production function, Y = AK0.3L0.7, with respect to K. As K increases, MPK falls (law of diminishing marginal product of capital). The more machines you have – holding A and N fixed – the less additional production you can get from an additional unit of capital. If you buy another computer and you do not have a worker to use the computer, the computer has little effect on your firm’s productivity! Holding K constant, what increases the MPK? Technology (A) and workers (N). Increasing A must increase the benefits of capital. All else equal, firms will want to invest more! What is the cost associated with purchasing capital? We defined this in class as the user cost of capital. Basically, we are going to focus only on interest rates (r) in this class (we will ignore the other parts of the user cost of capital – i.e., the depreciation rate and the maintenance costs). As interest rates increase, it is more expensive for firms to invest. Firms can get the funds to invest from two resources: a) b) Loans Retained earnings. It is important to remember that the real interest rate (r) increases, borrowing is more expensive. Remember, the real interest rate represents a profit to lenders. If a firm borrows, it has to pay the lender some profit for allowing it to borrow money. As the real interest rate increases, the cost to borrow increases. Firms should want to borrow less (and, as a result, invest less). Additionally, suppose the firm has some retained earnings. The firm can do two things with these retained earnings: It can stick it in a checking account or it can use it to fund an investment project (this is overly simplified, but you should be able to follow my logic). If they stick it in a checking account, they can earn some return on their retained 2 earnings. If they use it for investment (i.e., buy machines), they give up the interest they could have earned. The opportunity cost of investing is the real interest rate that they could have earned on their retained earnings. Either way, the cost of investing – via retained earnings or borrowing – is the real interest rate. (NOTE: In this class, we assume perfect capital markets—that is-- borrowing rates = lending rates = r. In practice, we would not observe perfect capital markets as there is some cost to financial intermediation.). When the benefits of increasing capital are greater than the costs, firms will invest more. The lower the interest rate, the more capital a firm will want, the lower the MPK. (This is analogous to the labor demand curve). So, there is a negative relationship between firm investment (I) and the real interest rate (r) (as r falls, I will increase). Why is there a negative relationship between I and r? The answer is because of the law of diminishing marginal product of capital. The more capital a firm has, the less they are willing to pay for an additional unit of capital. In other words, interest rates have to fall in order to induce them to invest more (and increase their capital stock). Suppose you have a world where interest rates are fixed: We can draw the relationship between r and I as such: r 0 r* I(A0) I*0 For a given interest rate (r*), the level of investment is I*0. This level of investment is drawn for some level of A and N. I sometimes make the distinction between A and Af (technology today and technology in the future (where the superscript f denotes the future)). Technically, Af is appropriate for driving investment decisions (because investment today affects K tomorrow – the marginal product of capital tomorrow, is 3 therefore appropriate). But basically, increasing A today will also increase A tomorrow (given that changes in A tend to be permanent). Suppose A increases permanently (A and Af both increase). How do we represent this graphically? We do so as such: r 0 1 r* I(A1) 0 I(A ) I*0 I*1 The firm will decide to invest more at every given interest rate. Why? Because as A increases, K is more valuable to the firm. So, they are willing to pay more for each additional unit of capital. <<This is exactly the same rationale as why the labor demand curve increases when A increases>>. As a result, when A increases, firms will invest more! So far, we have taken r as being given. We will model r in greater depth when we get to the Fed. As for now, we will just assume the Federal Reserve (the Fed) sets interest rates at some level r*. Summary: 1) 2) Decreasing r will Increase I (holding A and N constant) Increasing A will cause I to increase (holding r constant) In equilibrium, we care about both effects, if they occur, together! We will get to this more when we model the Fed. For simplicity, unless I specifically ask, WE WILL ASSUME N DOES NOT AFFECT CURRENT INVESTMENT (I)!!!! This is only for simplicity – it will make our analysis much easier! One final note: I is a demand side variable (i.e., Y = C + I + G). K is a supply side variable (Y = A K.3N.7). Changing I by 1 unit will increase K by one unit (tomorrow). 4 When we finally put all our models together, we will usually look at changes in today – holding K constant. Going back to our first lecture, we defined the ‘really long run’ as the time period in which K adjusts. Basically, we will look at deviations from Y* when talking about I and then talk about the growth in Y* when talking about how K changes. Keep this distinction in your mind! Some Caveats on Investment A few quick things to keep in mind when discussing investment response to interest rate changes: Late in the course, we will use these caveats to help shape our thoughts about the slope of the investment demand curve. If the investment demand curve is steep, a given change in interest rates will have little effect on investment. If the investment demand curve is flat, a given change in interest rates will have a large effect on investment. What affects a firm’s responsiveness to changes in current interest rates? 1. As a matter of fact, there is a lag between changes in interest rates and investment decisions. When firms see interest rates fall, it takes them time to actually spend the money. For example, suppose a firm sees interest rates go down and the firm decides to build a new production facility. Before construction can actually begin, the firm has to: a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. Find a plot for the facility. Survey the plot for environmental reasons. Higher an architect. Settle on some plans. Go to a bank for a loan. Get approved. Start excavating the land. etc……. My point is, there is often a lag between changes in r and changes in I. This is going to be important when we discuss how the Fed gauges the impact of their policy. This may not directly affect the slope of the investment demand curve, but it will affect how long changes in r turn into changes in I (and consequently changes in Y). When the Federal Reserve changes interest rates, GDP may not respond for awhile (economists usually think 6-9 months!). 2. Firms do not invest when the economic environment is uncertain. As we have discussed in class and as you will see in the course readings, this is particularly relevant for the current economic cycle. Because investments involve such large fixed costs AND because it is costly to disinvest (i.e., remove a new assembly line or tear down a new production facility), firms want to be extra sure about the economic environment before 5 they undertake large investment decisions. environment, the less investment will occur. The more uncertain the economic If firms are uncertain about the future, firms might not respond at all if the Fed cuts interest rates. This will make the impact of monetary policy (changes in interest rates by the Fed) small. In other words, if firms are uncertain about the future and do not invest when the Fed cuts interest rates, the investment demand curve will be steep! Changes in r will have small effects on changes in I. NOTE 1: When I say the Fed, I do NOT mean the federal government but the Federal Reserve Board of Governors 3. Firms care about future interest rates when making their investment decisions. Suppose a firm thinks interest rates will be even lower tomorrow. Suppose they have a project that they expect will have a high, profitable return. A forward-looking firm may wait until tomorrow before they undertake the investment decision. The reason is that when tomorrow comes, borrowing will be cheaper! It is not only current interest rates that affect firm investment decisions; it is also their expectation about future interest rates! When firms expect interest rates in the future to fall, their change in investment to current interest rate changes today will be small (i.e., a steep investment demand curve). 4. Finally, even though a firm wishes to borrow, lenders may not allow the firm to do so. Banks are operating in environments with only partial information. Suppose we both own small firms. From an outsider’s perspective, both my firm and your firm look identical. Both of us go to a bank and ask for a $10 million loan. You plan to invest your money in a highly productive venture (a new facility). I tell the bank that I want to do the same. But, the bank knows that one of our firms will fail (either mine or yours). Maybe, I do not have as good a management team as you do. However, the bank is unaware of that. All the bank knows is that historically, 50% of all small firms that look like ours will eventually fail. Because the bank cannot tell us apart and the bank knows that one of us may fail, the bank may not choose to lend to either of us. In this case, even if you wanted to invest, you may be prevented from doing so because a bank (optimally) chooses not to lend to you. The banks only have partial information and, as a result, will sometimes restrict credit to firms with worthy projects. We call such firms liquidity constrained. These firms want to borrow, but the banking system prevents them from doing so. We will discuss liquidity constraints in more depth as part of our consumption lecture (households are often liquidity constrained) in Topic 3 slides and in Notes 6 in the text. The banking system can play a key role in the amount of investment we observe in the economy. Sometimes, the banking system can dramatically reduce lending because they are facing uncertainty. This is called a credit crunch. In this case, interest rates are low and firms want to invest, it just so happens that there is no one who is willing to lend firms money. In this case, investment will be low (the banking system is important to macroeconomic health! ---- this will be important when we discuss Japan!). 6 If banks prevent us from borrowing when we want to, the investment demand curve will again be steep. Changes in interest rates will lead to less investment! Summary: Basically, all these caveats will be important when discussing the impact of the Fed on the macro economy. The Fed sets r in hopes of stimulating I. When discussing the impact of r on I, all of the above discussion (main analysis and caveats) will be important! Inventories as a Component of Investment As discussed in lecture 1, inventories are a component of investment. Compared to other components of investment, inventories are historically investment’s most volatile component (the other components of investment are purchasing machines and equipment, building production facilities and housing). When firms are building up inventories, investment will be increasing. When firms are drawing down inventories, investment will be falling! These measures show up in our measures of GDP. Suppose firms over-produced during the 1990s. (By over-produced, I mean that production was high relative to demand). In this case, inventories would be high (inventories are what equates supply and demand – this is done by including inventories as a part of a demand component, i.e. investment). Part of the reason why Y was so high in the late 1990s could be because firms were building up inventories (we will discuss why they may have been doing this in a few minutes). Suppose that all of a sudden, firms realized that they were over-producing. Furthermore, suppose nothing new happened to demand (consumers kept on consuming as always – i.e., consumer confidence remained high). If firms realized that they were producing too much (and inventories were piling up), firms would optimally choose to cut production a little – even though demand has not changed! In this case, firms would have been unrealistically optimistic about the future. When firms start cutting production, Y would fall! C, however, could still remain strong. Consumers would just be consuming the inventories as opposed to consuming newly produced products. If this is the case, the following is what we would expect to see in the data: I would fall (as inventories were drawn down). Y would fall (as I falls) C would stay high (firms would be consuming the inventories; hence the inventories would be falling). This is exactly what we saw in the late 1990s. As firm cut production (initially), why didn’t consumer confidence fall as the laid off workers became unemployed? We will discuss this shortly (firms may have not initially laid off their workforce – it is costly to 7 fire workers – they may have delayed the decision to see if demand increased in the near future). But, for now, let’s just focus on the inventories. Why would a firm optimally choose to increase their inventories? Suppose that a firm thought that demand would be high for their product in the future (suppose they thought that consumers would be spending much more in the future). Such firms may increase production today in hopes of meeting future demand. Firms that are optimistic about the future will produce more. These firms will be increasing their inventories. We say that firms will increase their ‘expected’ inventories. These inventories were the result of firm optimizing decisions (increase production today so as to meet the high demand tomorrow). If producers in the late 1990s thought that demand would be high in the future (i.e., the growth that occurred in the 1990s persisted into the early 2000’s), they may have consciously increased their inventory holdings. Do we see an increase in inventories during the late 1990’s? YES! The above chart represents the change in inventories (in billions of real dollars). Notice, the inventories were increasing dramatically during the late 1990s (roughly 9 years of positive inventory growth). The stock of inventories, thusly, was extremely high. If you put, on net, $40 billion in inventories in a warehouse in 1993 and another $40 billion, on net, in the warehouse in 1994, at the end of 1994 you would have at least $80 billion worth of inventories on hand. Positive changes in inventories cumulate to a high total. Firms kept building up inventories during the late 1990s. 8 Another reason inventories accumulate is because demand was lower than firms expected. Take this example, suppose I planned to sell 10 million boxes of cereal next year. Suppose I do not want any inventories at the end of next year (planned inventories will equal zero at the end of next year). Suppose further that during the next year, demand for my cereal was less than I expected. Suppose consumers only bought 6 million boxes of cereal. At the end of next year, I will have 4 million boxes of cereal left over as inventories. These inventories were unplanned. They resulted from the fact that demand was less than expected. Let’s pause and recap a little bit. Inventories are of two types – planned and unplanned. If a firm increases their planned inventories, it is a sign that businesses are optimistic about the future. If unplanned inventories are increase, it is a sign that demand is weak relative to the firm’s expectation. Understanding inventory movements can give us some key as to the current economic environment. Increases in planned inventories signal that firms believe the economy is doing well. Increases in unplanned inventories signal that demand is low relative to firm expectations. Let’s go back to the 1990s. Suppose firms planned the future would be good and as a result, increased their planned inventories (i.e., they kept thinking the economy would grow at 4% per year). Suppose that 2000 came along and the economy only grew at a normal 2.3%. In this case, firms were planning on selling a lot of products because they expected demand to be higher. What do they do with the extra products they had produced (because they thought demand was going to be high)? They keep them in storage. Unplanned inventories will go up. As firms realize that they had overproduced, what is their logical response? They will cut production. Why would they continue producing when they have all these unplanned inventories on their shelves? In this case, Y would fall! What would happen next? Inventories would be driven down. This is what we see happening in 2001! Inventories are declining rapidly (see chart above). Production stopped (slowed) and consumption remained high. In terms of GDP accounting, C was positive (high) and I was negative (or low). Part of the reason I was low was because the change in inventories (a component of I) was negative. The drawing down of inventories is a common component of EVERY recession (see above). Firms cut production, draw down their inventories and do not start producing again until all the inventories are gone. Notice from the graph above that at the end of every recession, inventories start increasing! A strong signal that a recession is over is that inventories start increasing (i.e., firms start producing again!). In this case, it is 9 planned inventories that would be increasing – firms want to replenish their stock of goods. Inventories started increasing in January of 2002. This is the period that I think the recession ended for that recession. A similar pattern can be seen during the recent recession. Firms seem to be building up their inventories. One question I often get is “How can I tell if inventories increase because planned inventories are increasing or because unplanned inventories are increasing?” This is a great question. In the data, what we see is inventories rising. Sometimes, we can survey firms to ask them if their inventory increase was planned or unplanned. Often, though, we look at the speed which inventories are adjusting. Firms (and households) usually adjust to “news about the future” slowly. That is, if firms get a signal that demand in the future will be higher, they increase their production a little today. Why? They like to smooth things over time. Plus, the increase in demand is only their expectation of the future. What if they are wrong? To mitigate the prospects of being wrong (and to smooth their production) they increase production a little extra this period (and inventories will increase a little bit this period). They do the same next period. As a result of increasing inventories gradually over time, they will have enough inventories in the future to meet the period of high demand. However, unplanned inventories change rapidly (in a statistical sense). When we enter a recession, people stop buying our product and inventories pile up quickly (in a short period of time). Summary: A rapid rise in inventories often signals that the increase was unplanned. A smooth rise in inventories often signals that the increase was planned. Note: We use statistical techniques to determine whether the increase was rapid or smooth (we just don’t look at the picture). Formal Summary: Inventories are a good predictor of future economic activity. Sharp declines inventories signal that firms have slowed down production. At the end of recessions, inventories start to accumulate again. 10