Justina Tavana - Biology

advertisement

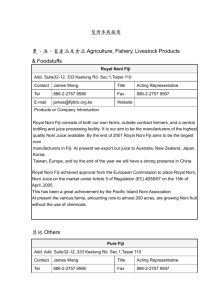

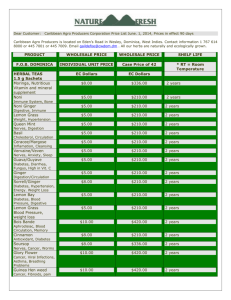

Antibacterial effects of traditionally prepared Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fruit juice and three brands of commercially produced “Noni” juices Justina Tavana Advisor – Dr. Goodwill ABSTRACT This study evaluated the antibacterial effects of traditionally prepared Noni fruit juice versus three different commercial products of Noni juice. The Kirby-Bauer method was used to test the antibacterial activity of the Noni extracts. Fifteen microliters of each extract was used to impregnate discs placed on Mueller-Hinton agar plates for antibacterial effects against Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. No zones of inhibition were present around the discs containing any of the Noni extracts. This may be due to the denaturing of the Noni juice through possible heating of the commercial extracts during preparation. The traditional extract, although not heated during preparation, also showed no antibacterial activity. INTRODUCTION: Morinda citrifolia (Noni) belongs to the Rubiaceae family. It is distributed and used throughout the South Pacific for both prevention and treatment for a wide range of health problems (Schechter 1998). Polynesian healers have used Noni leaves, seeds, roots, bark and flowers for over 2,000 years (Schechter 1999). The leaves or an infusion of the leaves are used as a massage ointment to treat body aches, various kinds of inflammation, boils and infected wounds (Whistler 1996). The juice of crushed flowers is applied to infections of the eye (Whistler 1996). The Noni fruit was and still is the most frequently used part of the plant (Locher et al. 1995). Noni is rapidly increasing in commercial success worldwide (Dixon et al. 1999). This success has come about with the help of traditional medicines and healers (Dixon et al. 1999). Cox (2000) points out that traditional uses of medicinal plants are important to the discovery and development of modern medicine. Braham (2000) noted that tribal knowledge can give clues for modern drug development. Mallavarapu (2000) and Singh et al. (2000) reported that a survey conducted in the USA showed that about 25% of prescription drugs contain one or more products of plant origin. 1 The fruit juice of Noni has been used to treat diseases, including cancer (Liu et al. 2001). Noni is the second most commonly used medicinal plant by Hawaiians, after Aloe vera (Abbot and Shimazu 1985). In Hawaii, Noni has been used traditionally to treat broken bones, deep cuts, bruises, skin infections, burns, sores, asthma, indigestion, urinary tract problems and colds (Abbott and Shimazu 1985 and Locher et al. 1995). Limyati and Juniar (1998) examined the microbiological properties of a traditional Indonesian medicine that contained M. citrifolia as one of its raw materials. The results demonstrated that M. citrifolia was one of the fruits that had the lowest level of microbe contamination and, therefore, suggested that it would be interesting to screen M. citrifolia for antibacterial activity. Western research of the antibacterial properties of Noni and especially the Noni fruit dates back to at least 1950 (Schechter 1998). Bushnell et al. (1950) noted that the Noni fruit showed antibacterial properties against Micrococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas. The purpose of this study was to compare the potential antibacterial effects of traditionally prepared M. citrifolia (Noni) juice with three different brands of commercially produced “Noni” fruit juices (Noni, produced by “Natural Styles Inc.”, Nevada; Pol’Noni, produced by “Polynesian Natural Health Products”, Tahiti; and Noni Pure, produced by “Nature’s Rx Inc.”, Oklahoma) against four standard bacteria (Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus). 2 METHODS Plant material and traditional extraction preparation Seven ripe Noni fruits (yellow) of variable sizes were placed in a glass jar. The jar was capped tightly and left alone until the fruit turned to pulp and the juice drained into the bottom of the jar. The juice was then strained through a cloth into a clean jar and refrigerated until ready for use. Methods followed directions of Folole Matagi (pers. comm.), a traditional Samoan healer, and Dixon et al. (1999). Assay for antibacterial activity The Kirby-Bauer method was used to test for antibacterial activity of the Noni samples. Forty Mueller-Hinton agar plates were each divided into three sections. Two plates were used to test each of the bacteria. Each two plate set was swabbed with one of the four bacteria: B. subtilis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus. One section contained a commercially prepared antibiotic disk used as a positive control disk (tetracycline). A second section contained a blank disk as the negative control. The remaining four sections contained discs impregnated with 15 microlitres of each of three commercial products (Noni, Pol’Noni, and Noni Pure) and the traditionally prepared Noni juice. This procedure was duplicated five times for a total of 40 plates, ten for each bacterium. The plates were then incubated at 37ºC for 48 hours (Mitscher et al. 1972). The diameter of zones of inhibition were measured in millimeters. 3 RESULTS The results of this study show that only the positive control (tetracycline) discs produced zones of inhibition. No zones of inhibition were seen on the discs containing any of the Noni extracts. CONCLUSIONS This study found that M. citrifolia fruit juice had no antimicrobial effects on B. subtilis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus. This experiment was repeated five times to ensure that the results were not attributable to methodological error. A possible reason for the results is that the Noni fruit juice may have been denatured through possible cooking in the preparation of the commercially prepared Noni products. This could have led to the loss of antimicrobial activity. However, the traditional Noni extract was not heated. Its lack of antibacterial activity may also be due to its preparation which may not have accurately mimicked the traditional extract method. Often these procedures are closely guarded family secrets (Goodwill pers. comm.). Low temperature could, likewise, affect lower antibacterial activity. The traditionally prepared extract was refrigerated before testing. Lastly, dosage might be a factor. It is recommended that further testing be done with fresh Noni extract without refrigeration or heating and at a variety of dosages. ACKKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Alexandra Paul and Roger Goodwill for serving as my advisors and for valuable discussions on my paper. I would like to thank Chris & Trisha Wilson of “Natural Styles Inc.” and Douglas Oba for donating the commercial Noni products used in this study. A sincere thank you also goes to the rest of the BYU-H Biology Department faculty for their assistance and constructive criticisms on this paper. Last but not the least, I have acquired much of the invaluable ethnomedical information for this study from traditional healer Folole Matagi, who has unfortunately passed away during the course of this project. I am deeply honored to have learned from her expertise. 4 Sources Cited Abbot, I. A. & C. Shimazu. 1985. The Geographic Origin of the Plants most commonly used for Medicine by Hawaiians. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 14: 213-222. Braham, M. 2000. Indigenous medicinal plants for modern drug development programme: Revitalization of native health traditions. Advances in Plant Sciences 13(1): 1-10. Bushnell, O. A., M. Fukuda, & T. Makinodan. 1950. The Antibacterial Properties of Some Plants Found in Hawaii. Pacific Science 4: 167-182. Cox, P.A. 2000. Will Tribal Knowledge Survive the Millennium? Science 287(5450): 4445. Dixon, A.R., H. McMillen, & N.L. Etkin. 1999. Ferment this: The Transformation of Noni, A Traditional Polynesian Medicine (Morinda Citrifolia, Rubiaceae). Economic Botany 53(1): 52-68. Goodwill, R. Biology professor BYU-H. Limyati, D.A. and B.L.L. Juniar. 1998. Jamu Gendong, a kind of traditional medicine in Indonesia: the microbial contamination of its raw materials and endproduct. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 63(15): 201-208. Liu, G. A. Bode, W. Ma, S. Sang, C. Ho, & Z. Dong. 2001. Two novel glycosides from the fruits of Morinda citrifolia (noni) inhibit AP-1 transactivation and cell transformation in the mouse epidermal JB6 cell line. Cancer Research 61(15): 5749-5756. Locher, C. P., M. T. Burch, H. F. Mower, J. Berestecky, H. Davis, B. Van Poel, A. Lasure, D. A. Vanden Berghe, & A. J. Vlietinck. 1995. Anti-microbial activity and anti-complement activity of extracts obtained from selected Hawaiian medicinal plants. Journal of Ethnopharmocology 49: 23-32. Mallavarapu, G.R. 2000. Contribution of medicinal plants to modern medicine. Journal of Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Sciences 22-23 (4A-1A): 572-578. Matagi, Folole. Traditional Samoan Healer. Laie, Hawaii. Mitscher, L. A., R. Leu, M. S. Bathala, W. Wy, & J. L. Beal. 1972. Antimicrobial Agents from Higher Plants. I. Introduction, Rationale, and Methodology. Lloydia 35(2): 157-166. Schechter, S. 1998. Noni: Island fruit bursting with benefits. Better Nutrition 60(9): 30. 5 Schechter, S. 1999. Nonu-Nature’s true adaptogen from the South Pacific. Total Health 21(2): 40-41. Singh, J., G.D. Bagchi, A. Singh, & S. Kumar. 2000. Plant based drug development: A pharmaceutical industry perspective. Journal of Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Sciences 22-23(4A-1A): 554-563. Whitsler, W.A. 1996. Samoan Herbal Medicine. Isle Botanica. Honolulu. p.21-22. 6 Antibacterial effects of traditionally prepared Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fruit juice and three brands of commercially produced “Noni” juices Justina Tavana Biology 493 Winter 2003 – BYU-Hawaii Advisor – Dr. Goodwill 7