Spanish-AmericanWar-Inquiry

advertisement

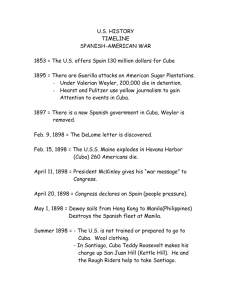

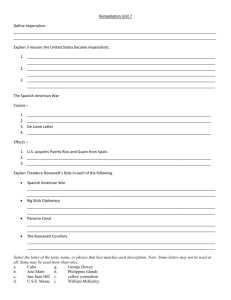

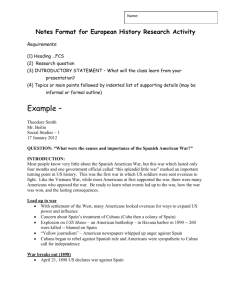

What really propelled the United States to declare war on Spain? Overview: “A splendid little war” is the way John Hay, ambassador to England, referred to the Spanish-American War in a letter to Theodore Roosevelt. Although the war lasted less than four months with few American casualties, the results of the war have forever changed the United States national identity and role in the world as an imperialist power. The implications of events leading up to the war were not unique to 1898 and analysis of the role of the major factors provides valuable insight into U.S. history. In 1890, the Bureau of the Census declared the interior frontier was closed, and many people began looking overseas for a solution to the mounting surplus of manufactured goods as well as new lands for resources, export market, and cheap labor. (Zinn, 1) The severe economic depression of 1893, which left 500 banks and 16,000 businesses bankrupt and millions of Americans without jobs compounded the temptation of pursuing overseas expansion. (Choices, 2) Fueling the political climate, the 1896 elections between William McKinley (R) and William Jennings Bryan (D) revealed how polarized the nation remained 30 years after the civil war (North vs. South / Populists vs. Northeast Bankers / Racial). Just ninety miles south of Florida, the Cuban fight for independence raged again against the Spanish colonial rule and captured public sympathies in the United States as General Weyler forced Cubans into concentration camps resulting in over 400,000 Cuban deaths. (Zinn, 3) The U.S.S. Maine was sent to Havana harbor to protect United States interests and exploded three weeks later on February 15, 1898. Immense public support for the war left McKinley with no other option than to request a declaration of war from congress in April 1898. Historian Stephen Ambrose said the United States “had to find some new outlet for our energy, for our dynamic nature, for this coiled spring that was the United States.” Through this inquiry, students will examine the underlying forces that led the United States to war with Spain. Students will examine primary and secondary sources relating to Cuban sympathies, U.S. economic interests and desire to become a world power, the role racism and religion played, and the impact of yellow journalism. The Treaty of Paris following the end of the war resulted in an explosion of opposing views as to the appropriate path for the United States. The Spanish-American War provides an understanding of how the U.S. emerged as an imperial power and reveals how the questions of national values of the 1890s are still relevant today. Multiple Objectives: a. Content Objectives -SW demonstrate knowledge of the changing role of the United States from late nineteenth century to WWI through the Spanish-American War. G.L.E. Component 3.3: Understands the geographic context of global issues and events. G.L.E. Component 4.1: Understands historical chronology. -Identify changes shaping United States’ international outlook in the 1890s. G.L.E. Component 4.3: Understands that there are multiple perspectives and interpretations of historical events. -Working with primary and secondary sources of evidence b. Higher Order Thinking Skills Objectives -Examine multiple causal factors and events leading ultimately to U.S. imperialism G.L.E. Component 2.4: Understands the economic issues and problems that all societies face. G.L.E. Component 1.3: Understands the purposes and organization of international relationships and United States foreign policy. G.L.E. Component 4.3: Understands that there are multiple perspectives and interpretations of historical events. -Critically analyze the role of competing forces in swaying public opinion and perception G.L.E. Component 4.2: Understands and analyzes causal factors that have shaped major events in history. -Revise hypotheses based on evidence through the process of inquiry G.L.E. Component 5.2: Uses inquiry-based research. G.L.E. Component 5.4: Creates a product that uses social studies content to support a thesis and presents the product in an appropriate manner to a meaningful audience. Grade Level: 11 Time: (3) 55min periods or (2) 90 minute blocks Course Placement: This inquiry will fit into 11th grade curriculum covering United States history 1890present. The inquiry directly addresses the changing role of the United States from 1890 to 1917 and U.S. imperialism. Students will have a working knowledge of the Monroe Doctrine as the major political foundation for support of Cuban independence from Spain and intervention in Latin America. Additional prior knowledge includes the shift from agriculture to manufactured goods and how the surplus of goods during the economic depression of 1893 affected U.S. economic interests. Students understand race relations in the U.S. and reasons for the polarized political atmosphere of the 1890s. Materials: Film - “Crucible of Empire” PBS 2007, Overhead Transparencies of Data Sets or Projector, handouts of the data sets, recording of “Remember the Maine”, white board markers Procedure: I. Engaging the students in the inquiry – “the hook” Show images of 9/11 attack and have students recall memories and reactions within themselves and from the United States. Have students raise hands and describe how the United States responded. Follow up by showing images of the U.S.S. Maine explosion in the Havana harbor and subsequent newspaper headlines. Give background information of the Maine while images are displayed. Ask the students to draw parallels between September 11th and the blowing up of the Maine. Analyze the documents for what the author/ photographer is trying to convey. (Alternate Hook: Play intro to the film “Crucible of Empire.” Engage students in questioning images and statements heard.) Explain to students that we are going to began an inquiry into the underlying causes of the Spanish-American War – a war that put the United States on a path to becoming a dominant imperial world power. II. Elicit Hypothesis A. Refer back to inquiry question: What really propelled the United States to declare war on Spain? Rephrase question if necessary to ensure all students understand we are looking for specific reasons – economic, societal, and historical, etc. B. Ask students to formulate hypothesis as to why the U.S. engaged in war with Spain. Have them raise hands and record their reasons/hypothesis on the board. After a good list has been recorded, take a straw poll to see which hypothesis have the most support. Ask students to discuss support for different hypothesis, and then write down their own hypothesis. Provide a stem if students are having difficulty. The main reason the United States declared war on Spain was… Let students know you will ask some of them to read their hypotheses out loud. (Play song “We Have Remembered the Maine” while students are formulating hypotheses) Randomly select 7-10 students to read their hypothesis to get an idea if students are grasping the objectives properly. III. Data Gathering and Processing Break students into groups of four to analyze the data sets. This will give students an opportunity to share their thoughts of possible ways the new evidence might alter their previous hypotheses. Be explicit that there is no single correct answer to the question and not all evidence is necessarily equal in value. Take a moment to revisit the differences between primary and secondary sources and that the data presented by no means reflects everyone’s values or thoughts in the U.S.. -As the data sets are presented, guide students through the evidence after some time has been given for them to discuss the evidence with their groups. After the data set has been analyzed and discussed, revisit the hypotheses on the board and ask if students would like to add, delete, or highlight hypotheses. Have students discuss reasoning if there are any disagreements. Repeat this process after each data set. -Handout timelines to students Data Set 1 – Cuban Sympathies -Show images portraying Cuba -Hand out data set 1 evidence. Data Set 2- Economic Interests and World Power As maps are displayed, ask students to identify Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines along with major cities. Have students make initial observations of their relationship geographically to the United States and the implications this may have economically and strategically. -Display map of Caribbean – note that Cuba is only 90 miles from the tip of Florida and in the route to the Panama Canal zone -Display map of Southeast Asia – note the proximity to China (access to markets)– Dewey’s squadron left Hong Kong for Manilla; 600 miles away -Distribute handout for Data Set 2 Data Set 3- Racism / Religion Before displaying images or distributing handouts, briefly discuss as a class two key concepts: Social Darwinism and Scientific Racism -Display images from data set 3 -Distribute evidence for data set 3 Data Set 4- Yellow Journalism Note-the term yellow journalism has nothing to do with race. -Distribute evidence for data set 4 -Display images IV. Conclusion / Revising Hypotheses After all data sets have been presented and discussed, students will finalize any hypotheses on the board. For homework, students will write a paragraph including a topic sentence (revised hypothesis) followed by at least three pieces of supporting evidence. The evidence can be drawn from the data sets or students can access additional sources (as long as sources are properly cited). The paragraph must address specific causal factor(s) driving the U.S. to war with Spain. The paragraph will be graded via a scoring rubric. Assessment: This inquiry utilizes both formal and informal assessments. The informal assessments are reached through hypotheses presented by students in class. A formal assessment will be addressed through the homework assignment. Formative assessments are achieved through possible hypotheses and questioning, and summative assessments will be accompliched through homework. Introduction Photos: – U.S.S. Maine sent January 1898 to Cuba to protect U.S. interests and citizens. Exploded February 15, 1898. C. G. Bush. "The Star in the East." Drawing for cartoon published in The World, [April 1898]. NYPL, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, Print Collection This original drawing expresses the angry end of restraint on the part of U.S. authorities and the public at the war's outbreak. Once again, the two dominant causes for war intervention are depicted as Cuban freedom and the destruction of the Maine. Sheet Music Cover for “We Have Remembered the Maine.” TIMELINE The Spanish American War (1898-1901) Timeline 1895: Cuban nationalists revolt against Spanish rule 1896: Spanish General Weyler (the "Butcher") comes to Cuba. 1897: Spain recalls Weyler Early 1898: USS Maine sent to Cuba February 9, 1898: Hearst publishes Dupuy du Lome's letter insulting McKinley. February 15, 1898: Sinking of the USS Maine February 25, 1898: Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt cables Commodore Dewey with plan: attack the Philippines if war with Spain breaks out April 11, 1898: McKinley approves war with Spain April 24, 1898: Spain declares war on the US April 25, 1898: US declares war on Spain May 1, 1898: Battle of Manila Bay (Philippines) May, 1898: Passage of the Teller Amendment. July 1, 1898: San Juan Hill taken by "Rough Riders" July 3, 1898: Battle of Santiago Spain's Caribbean fleet destroyed. July 7, 1898: Hawaii annexed July 17, 1898: City of Santiago surrenders to General William Shafter August 12, 1898: Spain signs armistice August 13, 1898: US troops capture Manila December 10, 1898: Treaty of Paris signed US annexes Puerto Rico, Guam, Philippines. January 23, 1899: Philippines declares itself an independent republic Led by Emilio Aguinaldo, the self-declared Filipino government fights a guerilla war against the US that lasts longer than the Spanish-American War itself. February 6, 1899: the Treaty of Paris passes in the Senate 1900: Foraker Act Some self-government allowed in Puerto Rico. 1901: Supreme Court Insular Cases March 1901: Emilio Auginaldo captured. 1901: Platt Amendment 1902: US withdraws from Cuba 1917: Puerto Ricans given US citizenship http://www.sparknotes.com/history/american/spanishamerican/timeline.html DATA SET 1 Note: Examine the way Cuba is portrayed. Note: Unlike the Ten Years' War (1868-1878), the Cuban Independence Movement of the 1890s was not ignored by the United States. This was partly due to sympathies resulting from the many Cuban nationalists living in the United States. “In 1896, General Weyler of Spain implemented the first wave of the Spanish "Reconcentracion Policy" that sent thousands of Cubans into concentration camps. Under Weyler's policy, the rural population had eight days to move into designated camps located in fortified towns; any person who failed to obey was shot. The housing in these areas was typically abandoned, decaying, roofless, and virtually unihabitable. Food was scarce and famine and disease quickly swept through the camps. By 1898, one third of Cuba's population had been forcibly sent into the concentration camps. Over 400,000 Cubans died as a result of the Spanish Reconcentration Policy.” “Crucible of Empire” PBS 2007. “Weyler is a fiendish despot, a brute, a devastator of haciendas, pitiless, cold, an exterminator of men. There is nothing to prevent his carnal brain from inventing torture and infamies of bloody debauchery.” The New York Journal, February 1896. (crucible of empire) “I think Hearst took up the Cuban independence movement as a jingoistic way to bring America together. We were a nation in that period that was at each other's throats. North was still angry at South. Populist farmers didn't like East Coast bankers. We had economic depression which created a panic. And Hearst saw that the way to pull everybody together was with some war.” Douglas Brinkley – Crucible of Empire On March 17, 1898, Vermont Senator Redfield Proctor (1831-1908) delivered one of the most significant speeches of the Spanish-American War era. After an observation visit to Cuba, Senator Proctor returned to the United States and told Congress about Cuba's bleak situation: "I went to Cuba with a strong conviction that the picture had been overdrawn. I could not believe that out of a population of one million six hundred thousand, two hundred thousand had died within these Spanish forts...My inquiries were entirely outside of sensational sources...What I saw I cannot tell so that others can see it. It must be seen with one's own eyes to be realized...To me the strongest appeal is not the barbarity practiced by Weyler, nor the loss of the Maine...but the spectacle of a million and a half people, the entire native population of Cuba, struggling for freedom and deliverance from the worst misgovernment of which I ever had knowledge..." – Crucible of Empire “No man’s life, no man’s property is safe. American citizens are imprisoned or slain without cause. American property is destroyed on all sides… Cuba will soon be a wilderness of blackened ruins. This year there is little to live upon. Next year there will be nothing. The horrors of a barbarous struggle for the extermination of the native population are witnessed in all parts of the country. Blood on the roadsides, blood on the fields, blood on the doorsteps, blood, blood, blood! Is there no nation wise enough, brave enough to aid this blood-smitten land?” – New York Journal (Choices, 9) DATA SET 2: Economic Interests and World Power Map Caribbean *A New Manifest Destiny This new manifest destiny first took the form of vigorous efforts to expand American trade and naval interests overseas, especially in the Pacific and Caribbean. Thus, in the Pacific, the United States took steps to acquire facilities to sustain a growing steam-propelled fleet. In 1878 the United States obtained the right to develop a coaling station in Samoa and in 1889, to make this concession more secure, recognized the independence of the islands in a tripartite pact with Great Britain and Germany. In 1893, when the native government in Hawaii threatened to withdraw concessions, including a site for a naval station at Pearl Harbor, American residents tried unsuccessfully to secure annexation of the islands by the United States. Development of a more favorable climate of opinion in the United States in the closing years of the century opened the way for the annexation of Hawaii in 1898 and Eastern Samoa (Tutuila) in 1899. In the same period the Navy endeavored with little success to secure coaling stations in the Caribbean and Americans watched with interest the abortive efforts of private firms to build an isthmian canal in Panama. American businessmen promoted establishment of better trade relations with Latin American countries, laying the groundwork for the future Pan American Union. And recurrent diplomatic crises, such as the one with Chile in 1891–1892 that arose from a mob attack on American sailors in Valparaiso and the one with Great Britain over the Venezuelan– British Guiana boundary in 1895, drew further attention to the southern continent. Stewart, Richard W. “The United States Army and the Forging of a Nation, 1775-1917.” American Military History. Volume 1. Center of Military History. Washington, D.C. 2005 *ALFRED THAYER MAHAN “As a nation launches forth, the need is soon felt for a foothold in a foreign land, a new outlet for what it has to sell, a new sphere for its shipping. The ships that thus sail must have secure ports and the protection of a navy.” *“In the interests of our commerce…we should build the Nicaragua canal, and for the protection of that canal and for the sake of our commercial supremacy in the Pacific we should control the Hawaiian islands and maintain our influence in Samoa….and when the Nicaragua canal is built, the island of Cuba…will become a necessity….The great nations are rapidly absorbing for their future expansion and their present defense all the waste places of the earth. It is a movement which makes for civilization and the advancement of the race. As one of the greatest nations of the world the United States must not fall out of the line of march.” –Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts (Zinn, 3) *“There was already a substantial economic interest in the island, which President Grover Cleveland summarized in 1896: ‘It is reasonably estimated that at least from $30,000,000 to $50,000,000 of American capital are invested in the plantations and in railroad, mining, and other business enterprises on the island. The volume of trade between the United States and Cuba, which in 1889 amounted to about $64,000,000, rose in 1893 to about $103,000,000.’” (Zinn, 8) *“By the 1890s, Spain was considered very low in the estimation of many, many Americans. Spaniards had been looming around our country through our formation years, and somehow we always felt a threat from them. They were not part of the either the Anglo-Saxon culture or French culture. And so we always saw Spain as being almost, ah, a sub-human European peoples.” –Douglas Brinkley (Crucible of Empire film) DATA SET 3: Role of Race and Religion Social Darwinism, Scientific Racism, Ethnocentrism *“It seems to me that God, with infinite wisdom and skill, is training the Anglo-Saxon race for an hour sure to some in the world’s future….The unoccupied arable lands of the earth are limited, and will soon be taken…. Then will the world enter upon a new stage of its history – the final competition of races, for which the Anglo-Saxon is being schooled…. Then this race of unequaled energy…will spread itself over the earth.” - Reverend Josiah Strong *“It is a glorious history our God has bestowed upon His chosen people; a history heroic with faith in our mission and our future; a history of statesmen who flung the boundaries of the Republic out into unexplored lands and savage wilderness; a history of soldiers who carried the flag across blazing deserts and through the ranks of hostile mountains, even to the gates of sunset; a history of a multiplying people who overran a continent in half a century; a history of prophets who saw the consequences of evils inherited from the past and of martyrs who died to save us from them; a history divinely logical, in the process of whose tremendous reasoning we find ourselves today.” “Shall the American people continue their march toward the commercial supremacy of the world? Shall free institutions broaden their blessed reign as the children of liberty wax in strength, until the empire of our principles is established over the hearts of all mankind?” “Hawaii is ours; Porto Rico is to be ours; at the prayer of her people Cuba finally will be ours; in the islands of the East, even to the gates of Asia, coaling stations are to be ours at the very least; the flag of a liberal government is to float over the Philippines…” “The rule of liberty that all just government derives its authority from the consent of the governed, applies only to those who are capable of self-government.” “…We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustee, under God, of the civilization of the world. God has marked us as His chosen people, henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world…We are not dealing with Americans or Europeans. We are dealing with Orientals. They are not capable of self government…Savage blood, Oriental blood, Malay blood, Spanish example- are these elements of self-government?...The Declaration of independence applies only to people capable of self-government.” Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana – from “March of the Flag” September 16, 1898 (Choices p.23) *Rudyard Kipling –excerpt from “White Man’s Burden” Note: a few years later Kipling won the Nobel Prize for literature Take up the White Man's burden-Send forth the best ye breed-Go bind your sons to exile To serve your captives' need; To wait in heavy harness, On fluttered folk and wild-Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child. Take up the White Man's burden-The savage wars of peace-Fill full the mouth of Famine And bid the sickness cease; And when your goal is nearest The end for others sought, Watch sloth and heathen Folly Bring all your hopes to nought. Take up the White Man's burden-Have done with childish days-The lightly-proferred laurel, The easy, ungrudged praise. Comes now, to search your manhood Through all the thankless years Cold, edged with dear-bought wisdom, The judgment of your peers! *Senator Henry Cabot Lodge “…What makes a race are their mental and, above all, their moral characteristics, the slow growth and accumulation of centuries of toil and conflict. These are the qualities which determine their social efficiency as a people, which make one race rise and another fall….it is on the moral qualities of the English-speaking race that our history, our victories, and all our future rest. There is only one way in which you can lower or weaken those characteristics and that is by breeding them out. If a lower race mixes with a higher in sufficient numbers, history teaches us that the lower will prevail…the lowering of a great race means not only its own decline but that of human civilization…” (Annals, p. 88-92) Data Set 4: Yellow Journalism Spanish-American war sometimes referred to as the first “media war.” The American press had no doubts about who was responsible for sinking the Maine. It was the cowardly Spanish, they cried. William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal even published pictures. They showed how Spanish saboteurs had fastened an underwater mine to the Maine and had detonated it from shore. As one of the few sources of public information, newspapers had reached unprecedented influence and importance. Journalistic giants, such as Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer of the World, viciously competed for the reader's attention. They were determined to reach a daily circulation of a million people, and they didn't mind fabricating stories in order to reach their goal. They competed in other ways as well. The World was the first newspaper to introduce colored comics, and the Journal immediately copied it. The two papers often printed the same comics under different titles. One of these involved the adventures of "The Yellow Kid," a little boy who always wore a yellow gown. Since color presses were new in the 1890s, the finished product was not always perfect. The colors, especially the Yellow Kid's costume, often smeared. Soon people were calling the World, the Journal, and other papers like them "the yellow press." "They colored the funnies," some said, "but they colored the news as well." A minor revolt in Cuba against the Spanish colonial government provided a colorful topic. For months now the papers had been painting in lurid detail the horrors of Cuban life under oppressive Spanish rule. The Spanish had confined many Cubans to concentration camps. The press called them "death camps." Wild stories with screaming headlines -- Spanish Cannibalism, Inhuman Torture, Amazon Warriors Fight For Rebels -- flooded the newsstands. Newspapers sent hundreds of reporters, artists, and photographers south to recount Spanish atrocities. The correspondents, including such notables as author Stephen Crane and artist Frederick Remington, found little to report on when they arrived. "There is no war," Remington wrote to his boss. "Request to be recalled." Remington's boss, William Randolph Hearst, sent a cable in reply: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures, I'll furnish the war." Hearst was true to his word. For weeks after the Maine disaster, the Journal devoted more than eight pages a day to the story. Not to be outdone, other papers followed Hearst's lead. Hundreds of editorials demanded that the Maine and American honor be avenged. Many Americans agreed. Soon a rallying cry could be heard everywhere -- in the papers, on the streets, and in the halls of Congress: "Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain." Buschini, J. “Yellow Journalism.” Small Planet Communications. 2000 http://www.smplanet.com/imperialism/remember.html *On February 9, 1898, the contents of a seized Spanish letter caused an international scandal that fueled anti-Spanish and pro-war feelings in the United States. While in Washington in the middle of December, Spanish ambassador Enrique Dupuy de Lôme wrote a personal letter to his friend José Canalejas who was in Cuba. The letter contained these derogatory comments about President McKinley and his policies concerning Cuba: Besides the natural and inevitable coarseness with which he repeats all that the press and public opinion of Spain have said of Weyler, "It shows once more that McKinley is weak and catering to the rabble and, besides, a low politician who desires to leave a door open to himself and to stand well with the jingos of his party." “The New York Herald needed a day, at least, to authenticate the letter. The Cubans said, ‘You don't have a day.’ They took it to Hearst. Hearst published it immediately, with huge, huge headlines, ‘Greatest Insult Ever to America: Spanish Insult Our President.’ And the Hearst papers now demanded, and other papers as well, that war was the only recourse.” – David Nasaw (excerpt from Crucible of Empire) Images: -Some images were completely fabricated- Resources: “Reluctant Colossus:America Enters the Age of Imperialism.” The Choices Program. Watson Institute for Internation Studies: Brown University. 2004 Zinn, Howard. “The Twentieth Century – A People’s History.” HarperPerennial. 1998 Williams, William Appleton. “The Tragedy of American Diplomacy.” W.W. Norton & Co. 1972 Perez Jr., Louis. “The War of 1898.” University of North Carolina Press. 1998 Ninkovich, Frank. “The United States and Imperialism.” Blackwell Publishers. 2001 Hoganson, Kristin L.. Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars.” Yale University Press. 1998 Film: “Crucible of Empire.” PBS. 2007 http://www.pbs.org/crucible