Lecture 1

advertisement

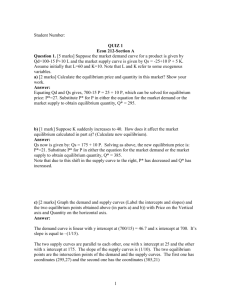

Updated:24.02.2006 ECON 501: MICRO-ECONOMICS Lecture 1 Topics that is covered: a. Theory of Supply and Demand b. Rationality c. Utility d. Inconsistent Preferences e. Slope of Indifference Curve f. Diminishing MRS g. Indifference Curves h. Income Constraint i. Demand Curves ECON 501 Nicholson Chapter 3, Part 1 INTRODUCTION The fundamental issue in microeconomics is to understand how the market works. It is really the “core” of economics and it’s called “price theory” at University of Chicago. Price theory tries to explain/predict organization of consumers, producers and factors of production The price theory is also the core of the whole economic science, maybe 90% of it, and microeconomics has also drifted into macroeconomics. True macroeconomics, in fact, is mostly “monetary economics” which is determination of price level. THEORY OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND is the main concept of microeconomics: P - S E How we arrive at equilibrium? What are the forces behind? What shapes the demand and supply curves? Pm D Q Quantity Ex: Water demand in Famagusta. What is the relative price of drinking to washing water? It is 15/1 including the coping costs, with proportions of 4% for drinking and 96% for washing water. How to alleviate the water shortage in Famagusta? Possible solution: raise the water prices and increase the quality of water in the water system. Consumers will get a better water service and still pay less than for water from the alternative sources they use now, i.e. vendors. Demand and supply concept can be applied to most market situations, even for complex cases. But, first we have to look behind the demand curve, and examine what is the nature of the economic model, which determines how the relative prices, incomes, tastes and preferences cause a certain combination of goods and services to be demanded. Fundamental assumption – individuals can and do make RATIONAL choices in order to maximize their overall satisfaction. 1 Second assumption – individuals live in a “certain” world and their decisions are based on full information available to them. In “economics of information” we address the issue of uncertainty and the trade-off between reducing the uncertainty and the cost of obtaining information. WHAT DO WE MEAN BY BEING “RATIONAL”? This means that we can organize our world into order. Assumption of perfect information may not be true, but this still allows our models to work. Under “rationality” of consumer decisions, there are three important rules which must be satisfied: 1. Completeness Rule. A B B P > P > = Consumers can make decisions either: B, or A, A. or and we can not make a choice with: A B P > P > B, and, at the same time A. 2. Transitivity Rule. Is the imposition of internal consistency in consumer’s choices. If A is preferred to B and B is preferred to C, then A is preferred to C. If A B A P > P > P > B, and C, then: C. 3. Continuity Rule. If A is preferred to B, than given any little incremental change around A, this new A’ is also preferred to B. It is implied that the function is smooth: If A P > B, A’ = A ± ΔA , A’ P > and then: B. UTILITY All three rules are used together to describe the concept of “utility”. It is a relative comparison, we do not measure the satisfaction from consumption itself, but we compare one situation with another. 2 Utility Theory It is possible to rank satisfaction from the consumption of a combination of goods according to their “utility”: P If A B, then: > U(A) P > U(B). We don’t try to measure the utility per se, but rather compare bundles A and B in terms of quantity of goods consumed. Assume that both X and Y are “goods,” not “bads”. Our starting point is A with quantity X0 and Y0 consumed, described as U(Y0,X0). If any movement from point A is to be made, then it would change the well-being of the consumer. Consumer will be better off if with the same quantity of Y0 he can have more of X, U(Y0,XN) P> U(Y0,X0) and this can be presented by line AB. At the same time, consumer will be also better off if he can have more of Y with quantity of being X0 constant, as depicted by line AC. Any point in the space between AB and AC will also make consumer better than A, and this direction would be preferred. U(YN,X0) P> U(Y0,X0) Consumer will be definitely made worse off if he is forced to consume less of both goods, which would be presented by movement to any location in area OY0AX0. Behavior of consumer is not clear in the case when consumption of one good is increasing while consumption of the other good is decreasing. Such cases are presented by shaded areas X0ABXN and Y0ACYN, and they also contain the “indifference curve.” good Y C Y2 Y1 Y0 Indifference Area YN Preferred Area A B Indifference Area Non-Preferred Area I O X0 X1 X2 XN good X The indifference curve is a combination of goods where the consumer is indifferent between the combinations of goods. On the curve a consumer is trading-off consumption of one good for the other good, while keeping his total satisfaction constant. 3 good Y Y0 Y1 Y2 Y3 I O X0 X1 X2 X3 good X Indifference curve maps out the space of a basket with two goods. It is a set of points with the same utility, regardless of how we actually measure utility. There are infinite many indifference curves – each representing a certain level of utility. INCONSISTENT PREFERENCES If A is preferred to B with A having the same number of Y but more of X. Then, E and D also belong to the same utility level U1 as point A. Assume that C belongs to the same utility level U2 as B, and point E is also included into set of points U2. But if point C has the same number of Y but more X, then C is preferred to D. good Y U1 U2 Y2 D C E A Y1 B U1 U2 O good X Therefore: C P > D, while A P > B, This is a contradicting statement if C = B and D = A. Such preferences are inconsistent. u (C) = u (B) and u(D)= u(A) 4 SLOPE OF INDIFFERENCE CURVE Slope of indifference curve is important. What is the slope of indifference curve? Slope = (Y1-Y0)/(X1-X0) = (1-3)/(5-4) = - 2 Taking a negative of the slope of indifference curve gives us the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) of Y for X. Marginal rate of substitution simply indicates how many units of Y consumer is ready to give up to get one more unit of X. MRS Y X UU1 Ex: Y0 = 3 X0 = 4 Y1 = 1 X1 = 5 MRS = - (1-3) / (5-4) = 2/1 =2 good Y Y0 Meaning that at this point consumer is equally happy if he trades 2Y for 1X. However, if we move further, the MRS Y1 will decline: Y2 Y1 = 1 X1 = 5 Y2 = 0.5 X2 = 6 MRS = - (0.5-1) / (6-5) = 0.5 Y3 O 5 I X0 X1 X2 X3 good X DIMINISHING MRS Concept of diminishing MRS holds for both goods: as we expand consumption of X we will be willing to give up less and less of Y. This requires continuity in the shape of the indifference curve. NO KINKS ! In figure below, A and B represent linear consumption of two goods. Any point in between A and B, let’s say C, will be preferred to A or B. Concept of diminishing MRS is assumed as normal behavior. Exclusion to this rule is the case of an addiction to something (drugs, etc.) Addictive behavior, however, can also be modeled. good Y Y0 Y1 Y2 Y3 I O X0 X1 X2 X3 (X1–X0) = (X2–X1) = (X3–X2) (Y1–Y0) > (Y2–Y1) > (Y3–Y2) MRS1 > MRS2 > MRS3 > MRSN 6 good X DIFFERENT TYPES OF INDIFFERENCE CURVES There are two cases that are the extremes which bound our analysis. If indifference curve has a constant, not diminishing MRS, then this is a “perfect substitutes” case. MRSA = MRSB = MRSC = MRSD Ex: different brands of gasoline, different brands of bottled water… good Y A B C D I U1 U2 O U3 good X If indifference curves look as in the figure below, this is a case of “perfect compliment” goods. When consumer has Y0 and X0, then adding more of X or Y alone does not increase utility. Ex: bicycle and tires, creamer and coffee… good Y U2 U1 U0 Y0 O X0 X1 X2 good X INCOME CONSTRAINT 7 There are constraints on the “wish-list” of the consumer. For our course, we analyze only “this period” preferences, but we can easily model “life-time” preferences. One of the problems in society is that people TODAY may not care about people who will be living TOMORROW, i.e. there is budget constraint that applies over time. Concept of “over-lapping generations”. Social security in many countries (Europe, Italy, Germany, partly US, TRNC) is suffering from this inter-generation problem. But some countries addressed this issue long ago (UK), others are still trying to ignore it. Let’s start with a budget constraint where we need to specify 3 things: I income during period Px price X Py price Y which give us the budget constraint: I = Px*X + Py*Y Ex: I = 10 income during period Px =1 price of Soft drink Py =2 price of kebab which give us the budget constraint: 10 = 1*X + 2*Y If X = 0 (no soft drinks), then Y = 5, and if Y = 0 then X = 10. good Y 5 I/PY Non-Affordable Affordable I/PX O 10 If we have 3 goods, and Pz = 0.5 which is the price of a salad: 10 = 1*X + 2*Y + 0.5Z If X=0 and Y=0 then Z=20 If X=0 and Z=0 then Y=5 If Z=0 and Y=0 then X=10 8 good X With 3 goods we have a plane, rather than a budget line. The consumer will consume at a point where utility hits the budget plane. good Y 5 20 good Z 10 good X The figure below shows a case when only one good will be consumed, the whole income will be spent on X. Slope of budget line is Py/Px = 5/10 = ½ If only one good is consumed, it means the price of the second good is too high, and only when the price of the second good changes – consumer will start purchasing the second good. good Y U0 U1 U2 U3 5 10 O good X DERIVING DEMAND CURVES FROM INDIFFERENT CURVES 9 It was thought that demand curves derive their slope from diminishing marginal utility, however this is not necessarily true. Indifference curve allows us to get the same result as if we had the assumption of diminishing marginal utility. Given the fixed amount of income and fixed price of X, if price of Y changes, the budget line changes its slope, which translates into more units of Y consumed. Quantity of Y demanded increases. This is also called a change in the quantity demanded. Py0 > Py1 > Py2 Y0 < Y1 < Y2 Price Y good Y I/PY2 Y2 Y1 u2 I/PY1 Y0 I/PY P Y0 P Y1 u1 0 u0 P Y2 I/PX With Oan increase in income of10the consumer, we see the demand curve O Y0 shifting Y1 Yat2 each 10 price good Y good X level. Notice, that prices of the goods are kept constant and only income is changed. This is illustrated below and called a “change in demand.” good Y Price Y D2 Y2 D1 Y1 Y0 O D0 I2 I1 PY0 I0 O good X Y0 Y1 Y2 good Y DEMAND FUNCTION IS NOT RELATED TO THE UTILITY INDEX USED The same set of indifference curves will give us the same demand function. The utility index used does not matter as long as it is a monotonic transformation, i.e. ordering of choices is preserved. Indifference curves allow us to derive a demand curve without giving a specific value to utility. 10 Any monotonic transformation of the values given to the indifference curves give us the same demand curve. I3 good Y good Y I2 I2 I1 I1 100 I0 I3 130 I0 80 95 65 60 40 40 O O good X MU of income is constant good Y MU of income is increasing I3 I2 I1 70 I0 63 55 40 O good X good X MU of income is decreasing 11