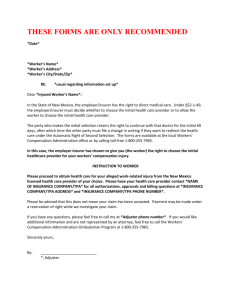

[2010] NSWWCCPD 91 - Workers Compensation Commission

advertisement

![[2010] NSWWCCPD 91 - Workers Compensation Commission](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008613591_1-991e817665280fc440fc47615e999790-768x994.png)

Issue 9: September 2010 On Appeal Welcome to the ninth issue of ‘On Appeal’ for 2010. Issue 9 – September 2010 includes a summary of the August 2010 decisions. These summaries are prepared by the Presidential Unit and are designed to provide a brief overview of, and introduction to, the most recent Presidential and Court of Appeal decisions. They are not intended to be a substitute for reading the decisions in full, nor are they a substitute for a decision maker’s independent research. Please note that the following abbreviations are used throughout these summaries: ADP AMS ARD COD Commission DP MAC Reply WPI 1987 Act 1998 Act 2003 Regulation 2006 Rules Acting Deputy President Approved Medical Specialist Application to Resolve a Dispute Certificate of Determination Workers Compensation Commission Deputy President Medical Assessment Certificate Reply to Application to Resolve a Dispute Whole Person Impairment Workers Compensation Act 1987 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Workers Compensation Regulation 2003 Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2006 Level 21 1 Oxford Street Darlinghurst NSW 2010 PO Box 594 Darlinghurst 1300 Australia Ph 1300 368018 TTY 02 9261 3334 www.wcc.nsw.gov.au Index Presidential Decisions: Martin v R J Hibbens Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 83 .......................................................... 4 Whether employment connected with New South Wales; s 9AA of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; meaning of “usually works”, “usually based’, and “principal place of business” ..............................................................................................................................4 Freeman v T H Freeman Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 88 ..................................................... 7 Section 55 of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; s 74 of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; application for increase in consent award of weekly compensation; failure by insurer to issue a notice disputing claim; failure by employer to file a wage schedule; failure by employer’s solicitor to address issues on appeal .............................................................................................................................................7 Warwar v Speedy Courier (Australia) Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 92 ................................ 9 Lump sum compensation; two injuries; circumstances in which the effects of multiple injuries can be aggregated to meet the threshold for compensation for pain and suffering in s 67 of the 1987 Act; section 322 of the 1998 Act ; consideration of the principles in Department of Juvenile Justice v Edmed [2008] NSWWCCPD 6; construction of complying agreement under section 66A of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; principle of objectivity; relevance of surrounding circumstances; application of principles in Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd and others [2004] HCA 52; 219 CLR 165..................................................................9 Lauda Enterprises Pty Ltd v Akkanen [2010] NSWWCCPD 91.......................................... 12 Boilermaker’s deafness; whether impairments from separate claims can be aggregated to meet the threshold for compensation for pain and suffering in s 67 of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; s 322 of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 ..................................................................................................... 12 Qantas Airways Limited v Watson (No 3) [2010] NSWWCCPD 86 .................................... 14 Reconsideration; s 350(3) Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 ................................................................................................................................... 14 Rail Corporation New South Wales v Crilly [2010] NSWWCCPD 84 ................................. 16 Psychological injury; expert evidence; ss 9A and 11A of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; adequacy of reasons, and disease. .......................................................................... 16 Haydar Al-Nouri v Al-Nouri Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 85 .............................................. 19 Section 319 of the 1998 Act; medical dispute; validity of Registrar’s referral of medical dispute to an AMS; status of a MAC following invalid referral; determination of the Commission operating as a res judicata. ............................................................................ 19 Falee v Harris Farm Markets Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 82 ............................................ 22 Injury; claim for lump sum compensation; referral to Approved Medical Specialist .............. 22 Bozinovski v Sydney South West Area Health Service – Fairfield Hospital [2010] NSWWCCPD 89 .................................................................................................................... 24 Failure to give reasons; failure to consider and analyse medical evidence; failure to consider worker’s evidence of continuing symptoms ......................................................................... 24 Chhong Heng Taing t/as The Arcade Pharmacy v Gauci [2010] NSWWCCPD 90 ............ 26 Proof of injury; evidence of disease; Part 18 Rule 4(4) of the Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2006, substitution of party to proceedings. ........................................... 26 2 Mitchell v South West Area Health Service [2010] NSWWCCPD 87 ................................. 28 Nature of issues in dispute; whether insurer disputed injury; section 74 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; nature of pathology from injury ......... 28 Port Macquarie Hastings Council v Crowe [2010] NSWWCCPD 93 .................................. 30 Unreasonable rejection of suitable employment, s 40 (2A) and (2B) of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; ability to earn in suitable employment, s 40(2)(d). ....................... 30 3 Martin v R J Hibbens Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 83 Whether employment connected with New South Wales; s 9AA of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; meaning of “usually works”, “usually based’, and “principal place of business” Roche DP 4 August 2010 Facts: Ms Bianca Martin worked for the respondent and other employers doing general forestry work from the year 2000 to January 2006. She generally worked in southeast Queensland, northern New South Wales and sometimes Victoria. It was the worker’s evidence that from the year 2000 she worked a number of broken periods of employment. She would work for the respondent when it could offer her periods of work and between those periods of work any other employer who was offering work. A letter from the respondent dated 19 February 2008 identified Queensland work for the worker from 19 January 2003 to 25 May 2003, Queensland work for the worker from the week ending (w/e) 24 July 2005 to the w/e 11 December 2005, NSW work for the worker for the w/e 18 December 2005, Queensland work for the worker for the w/e 25 December 2005 to the w/e 30 December 2005 and NSW work for the worker for the w/e 8 January 2006 to 5 February 2006. The worker gave evidence that her last period of work for the respondent was from approximately November 2005 to early February 2006. That period involved both Queensland work and New South Wales work. On 31 January 2006 the worker attended a property known as “Sandilands” at Old Lawrence Way, Tabulam, in northern NSW in working for the respondent. In the course of spraying designated areas she injured herself when she stepped into a hole and fell. The worker also gave evidence that when she worked for the respondent, all the equipment she used would either be delivered on site, or collected by her, from the respondent’s principal place of business in New South Wales. The worker’s further evidence was that after the work at “Sandilands” had been completed, and it was “nearly completed”, she was intending to work in Queensland for a short period and then return to New South Wales where she believed she would “relocate” and work for the respondent for a period of at least two years because of a lucrative contract this respondent had obtained. The Arbitrator found that the s 9AA(3)(a) test identified a state of connection of Queensland. He found that the worker’s employment could be characterized as short periods with many employers. He also found that the worker spent the majority of her time working in Queensland with 64% of her total earnings coming from employment in Queensland, and 36% coming from work in New South Wales. He considered that to be a good measure of the “period of her employment and connection with the State”. Held: Arbitrator’s determination revoked; remitted to Registrar for referral to an Approved Medical Specialist for assessment. 1. The purpose of the legislation that introduced s 9AA into the 1987 Act was to “eliminate the need for employers to obtain workers compensation coverage for a worker in more than one jurisdiction” and to ensure that workers “working temporarily in another jurisdiction will only have access to the workers compensation entitlements 4 – and common law benefits – available in their home State or ‘State of Connection’ and to provide certainty for workers about their workers compensation entitlements and ensure that each worker is connected to one jurisdiction or another””: The Parliamentary Secretary, the Hon Ian MacDonald, second reading speech, NSW Legislative Council, 4 December 2002. 2. The terms of s 9AA(3) provide a series of cascading tests for determining the State with which a workers’ employment is connected. If no answer is provided by s 9AA(3)(a), one moves to the next test in s 9AA(3)(b) and so on. If no State is identified by the three tests in s 9AA(3), a worker’s employment is connected with New South Wales if he or she is in New South Wales when the injury happens and there is no place outside Australia under the legislation of which the worker may be entitled to compensation for the same injury (the ‘location’ test) (s 9AA(5)). 3. In relation to s 9AA(3)(a) the import of the words “in that employment” in the phrase “the State in which the worker usually works in that employment”, concentrating on the provision and the provisions with which it interacts, means “in that [contract of] employment”; not in that general area of employment such as a trade or profession, such as forestry work. However, it extends to both a contract of service and the kind of contract for services contemplated by Schedule 1 of the 1998 Act: at [63] to [65] 4. The evidence was unsatisfactory when considering the contract of employment. From the limited evidence available it appeared that there were at least three, and possibly four, contracts of employment between the worker and the respondent. Alternatively there was the possibility of two contracts of employment dividing the third contract. 5. Given that s 9AA(3)(a) concerns where the worker usually works in that employment, and as the injury occurred in the contract of employment between the worker and the respondent that was existing from 20 November 2005 to 31 January 2006, the question was where the worker usually worked for that contract of employment. 6. At [62] the meaning of “usually” in “usually works” in keeping with Hanns v Greyhound Pioneer Australia Ltd [2006] ACTSC 5 was adopted: it is where the worker “habitually or customarily works”, or works “in a regular manner”. Even if it were open to have the entire employment relationship between the worker and employer as a frame of reference rather than just the employment contract during which the injury was received, which was open to doubt, no one state could be identified as the one in which the worker “usually worked” [62]. 7. Within the contract from 20 November 2005 to 31 January 2006, and for her other contracts with this employer, there was no State or no one State “where [the worker] habitually or customarily worked in her employment with R J Hibbens [or] in a regular manner”. The only conclusion that was reasonable was that she worked in Queensland for this employer for part of the time and in NSW for part of the time. Further, s 9AA(6) provided no assistance on the facts. All that could be said about her relevant work history was that she worked according to demand (at [71]). There was no probative evidence of the parties’ intentions (at [72]); and there was no evidence of “temporary arrangements” (at [73]) to disregard whatever assistance that could give. 8. In relation to s 9AA(3)(b), the correct test for determining where a worker was “usually based” is that set out in Tamboritha Consultants Pty Ltd v Knight [2008] WADC 78, considering factors including a camp site or accommodation provided by an employer; and where a worker is usually based, may coincide with the place where the worker usually works, but that need not be necessarily so. The evidence in this case was that the worker’s base moved with her (at [79]). The lack of evidence made it impossible to apply the test. 5 9. In relation to s 9AA(3)(c), an employer’s principal place of business is not necessarily the same as its principal place of business registered with ASIC under the Corporations Act, as a business need not be a corporation and not be registered for that reason. Rather, the employer’s principal place of business means “chief, most important or main place of business from where the employer conducts most or the chief part of its business”. Ms Martin’s evidence as to where she went to obtain equipment and the address shown on the letter from the respondent indicated the main place of the respondent’s business was in Kyogle in New South Wales. 10. In relation to s 9AA(5), the location test, Ms Martin’s employment was arguably connected with New South Wales as she was injured whilst working in New South Wales and there was no place outside Australia under the legislation of which she may be entitled to compensation. 11. The following principles were extracted from the authorities (at [60]): a. regard should always be had to the terms of the contract of employment; b. “usually works” means the place where the worker habitually or customarily works, or where he or she works in a regular manner (Hanns at [26]). It does not mean the place where the worker works for the majority of time (Knight at [76]) and is not simply a mathematical exercise (Avon Products Pty Ltd v Falls [2009] ACTSC 141 (Falls) at [43]), though the time worked in a particular location will naturally be relevant. It will also be relevant to look at where the worker is contracted to work (Falls). Regard must be had to the worker’s work history with the employer and the parties’ intentions, but “temporary arrangements” for not longer than six months within a longer or indefinite period of employment are to be ignored. Whether an arrangement is a “temporary arrangement” will depend on the parties’ intentions, which will be ascertained by looking at the worker’s work history and the terms of the contract. A short-term contract of less than six months that is not part of a longer or indefinite period of employment will not usually be a “temporary arrangement” (Knight); c. “usually based” can include a camp site or accommodation provided by an employer (Knight at [83]). Where a worker is usually based may coincide with the place where the worker usually works, but that need not necessarily be so. In considering where a worker is “usually based”, regard may be had to the following factors, though no one factor will be decisive: the work location in the contract of employment, the location the worker routinely attends during the term of employment to receive directions or collect materials or equipment, the location where the worker reports in relation to the work, the location from where the worker’s wages are paid, and d. an employer’s “principal place of business” is the most important or main place where it conducts the main part or majority of its business (Knight at [66]). It will not necessarily be the same as its principal place of business registered with ASIC. 6 Freeman v T H Freeman Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 88 Section 55 of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; s 74 of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; application for increase in consent award of weekly compensation; failure by insurer to issue a notice disputing claim; failure by employer to file a wage schedule; failure by employer’s solicitor to address issues on appeal Roche DP 16 August 2010 Facts: The worker, Mr Freeman, injured his left ankle in the course of his employment with the employer in 1994. The employer was a family company that conducts an electrical contracting business controlled by the worker. Mr Freeman also conducted his own business as a music teacher and was a volunteer with the Rural Fire Service. Mr Freeman settled proceedings in the Compensation Court of New South Wales in 1997 for a 15 per cent permanent loss of use of his left leg at or above the knee, together with compensation for pain and suffering. In 2003 there was an agreement for a further five per cent permanent loss of efficient use of the left leg at or above the knee. The parties also reached an agreement for weekly compensation under s 40 in the sum of $200 per week from November 1999 to date and continuing. Mr Freeman underwent surgery on his left ankle in November 2005 and was totally unfit for work from 20 November 2005 until 28 February 2006. In July 2006, Mr Freeman claimed weekly compensation at the maximum statutory rate for a worker with a dependent wife and child. In 2008, Mr Freeman made a claim in the Commission for additional lump sum compensation. The Commission referred the application for assessment to an Approved Medical Specialist. The Commission issued consent orders on 14 August 2009 stating that Mr Freeman had no further entitlement to lump sum compensation. In an application filed on 6 January 2010, Mr Freeman sought a review under s 55 of the consent award of $200.00 per week. He claimed weekly compensation in the sum of $1,500.00 from 13 July 2006 to date and continuing and claimed a dependent wife and one child. The Arbitrator made an award for weekly payments of $200.28 from 13 July 2006 to 30 June 2007, together with the statutory rate for a dependant son; $222.15 from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2008, together with the statutory rate for a dependant son; and $120.38 from 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2009, together with the statutory rate for a dependant son until 1 December 2008 and continuing. Mr Freeman brought an appeal stating the Arbitrator had erred in reducing his weekly compensation and in failing to properly assess his s 40 entitlements in circumstances where the employer had not sought a reduction, the insurer had not served a s 74 notice and had not filed a wage schedule. Held: Arbitrator’s determination of 16 April 2010 revoked and the matter remitted to a different Arbitrator for redetermination 1. The employer conceded that the only application before the Commission was Mr Freeman’s application for an increase in weekly compensation. [22] 7 2. The change in circumstances sufficient to trigger a review under s 55 is not restricted to a change in the worker’s medical condition but includes: a) Where a worker’s physical condition as a result of the injury has either improved or deteriorated: Manly Municipal Council v Dodds [1961] WCR 212; b) Where there has been a change as to dependency: Edmunds v Hetton Bellbird Collieries Ltd [1959] WCR 206; c) Where a worker’s earnings have changed: Englefield Collieries Ltd v Roberts (1932) 25 BWCC 558; d) Where there has been a general rise in the level of wages prevailing in the community: Producers Meat Supply Co Pty Ltd v McKinley [1950] WCR 149, and e) Any change in the criteria for entitlement to benefits under the legislation: Powell v Metropolitan Coal Co Ltd [1966] WCR 213. (Workers Compensation (New South Wales) 2nd edn, Butterworths, 1979, by CP Mills at 481) [23] 3. The Arbitrator did not err in relying upon a change in financial circumstances relative to 2003. The evidence clearly established that wage rates had moved since 2003. [24] 4. The employer’s submissions failed to adequately address the issues. The submissions that Mr Freeman’s application for an increase in weekly payments was “no more than creative accountancy” and that the findings made were “consistent with the medical evidence” were unhelpful. 5. The employer failed to make submissions on the fact there was no s 74 notice or a wages schedule from the employer. [25]-[27] 6. The employer submitted that, though the difference between probable earnings and ability to earn was $301 per week, there should have been an adjustment to Mr Freeman’s award for the following discretionary factors: Mr Freeman’s income from his music business was “probably greater than” shown in his tax return, and Mr Freeman carried out activities with the Rural Fire Service. 7. The employer’s submissions were untenable because: a) They incorrectly asserted that Mr Freeman earned the same from his music business as he did from his electrical business; b) They wrongly suggested that Mr Freeman’s income from his music business was a discretionary factor. It was a factor to take into account at step 1 of Mitchell, and c) There was no evidence that Mr Freeman’s activities with the Rural Fire Service reduced his ability to work. It was difficult to see that it was a discretionary factor. 8 Warwar v Speedy Courier (Australia) Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 92 Lump sum compensation; two injuries; circumstances in which the effects of multiple injuries can be aggregated to meet the threshold for compensation for pain and suffering in s 67 of the 1987 Act; section 322 of the 1998 Act ; consideration of the principles in Department of Juvenile Justice v Edmed [2008] NSWWCCPD 6; construction of complying agreement under section 66A of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; principle of objectivity; relevance of surrounding circumstances; application of principles in Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd and others [2004] HCA 52; 219 CLR 165 Roche DP 25 August 2010 Facts: Mr Warwar, the appellant, started work with Speedy Courier (Australia) Pty Ltd, as a trolley collector at a Bankstown shopping centre in early 2007. On 22 February 2007, he injured his lower back closing a heavy door on a trailer. Mr Warwar did not return to work after his injury. On 18 August 2008, whilst driving home after having received osteopathic treatment for his back, Mr Warwar was involved in a car accident in which he injured his neck and experienced increased symptoms in his lower back. Dr Giblin examined Mr Warwar and assessed a 5% WPI as a result of the lumbar spine injury on 22 February 2007 and 6% WPI as a result of the injury to the cervical spine and lumbar spine on 18 August 2008 (5% WPI neck and 1% additional WPI for the lumbar spine). Mr Warwar claimed compensation for an 11% WPI as a result of both injuries, together with $25,000 for pain and suffering. The respondent’s insurer, (QBE), in a letter dated 10 June 2009, offered to settle the claim for lump sum compensation based on Dr Giblin’s assessments (5% WPI as a result of injury on 22 February 2007 and 6% WPI as a result of injury on 18 August 2008), but declined to make an offer under s 67 because the claim did not meet the threshold for that compensation. Mr Warwar accepted the s 66 offer but disputed that he had no entitlement under s 67. The parties signed a s 66A Complying Agreement. This referred to a date of injury of 22 February 2007 and a WPI of 11%. It made no provision for the payment of compensation for pain and suffering. Mr Warwar filed an application in the Commission seeking compensation under s 67. The only issue in dispute was whether the injuries could be aggregated to satisfy the 10% threshold in s 67. The Arbitrator determined that Mr Warwar’s injuries could not be aggregated and he failed to meet the s 67 threshold. Mr Warwar argued on appeal: a) the s 66A complying agreement was binding on the parties. It only referred to the first injury and a WPI of 11% and the Commission must give effect to its terms and therefore award s 67 compensation; b) his permanent impairment assessment should be aggregated under s 322 of the 1998 Act, resulting in one whole person impairment of 11%, and 9 c) the injuries on 18 August 2008 were sustained when he was on a journey under s 10(3) after having medical treatment for the first injury and therefore these injuries resulted from the first injury. Held: Arbitrator’s determination confirmed. Section 66A 1. In the absence of any exemptions as set out in s 66A(3), the complying agreement was a written agreement and was to be interpreted according to the usual principles of contract law. This is an exception to s 234 of the 1998 Act which prevents a party contracting out of the terms of the 1987 and 1998 Acts. 2. The principles relevant to the construction of a contract were set out by the High Court in Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd and others [2004] HCA 52; 219 CLR 165 at [40]. 3. The fundamental principle is what reasonable parties would take a clause to mean at the time of making the contract, taking into account the text and structure of the written agreement and content of the surrounding circumstances known to the parties (Synergy Protection Agency Pty Ltd v North Sydney Leagues Club Limited [2009] NSWCA 140). 4. The surrounding circumstances known to the parties included Dr Giblin’s report and QBE’s letter dated 10 June 2009. On an objective view, the complying agreement compensated Mr Warwar for separate injuries that resulted from separate and distinct incidents. It was never the purpose or intention of the complying agreement to admit that Mr Warwar had met the threshold for s 67 compensation. QBE had expressly declined to make such an offer. Section 322 5. The principles discussed in Department of Juvenile Justice v Edmed [2008] NSWWCCPD 6 at [26] and [27], namely that impairments that have resulted form “the same injury” (same pathology) are to be assessed together to assess the degree of permanent impairment, were applicable. 6. The neck injury from the car accident was not the same injury as the low back injury sustained in 2007 and could not be aggregated to the impairment for the 2007 back injury. 7. The worker’s complaints and the medical evidence established that the lower back injury (pathology) in 2008 was an aggravation of the L4/5 disc protrusion caused in the first incident. It was therefore appropriate to aggregate those impairments. Mr Warwar suffered only a 1% impairment as a result of the injury to his lumbar spine in the car accident in 2008. This together with the 5% from the 2007 injury did not exceed the s 67 threshold. Results from 8. Mr Warwar’s submission that the need to travel for medical treatment as a result of the first injury exposed him to the risk of injury and he would not have been exposed to the negligence of another driver if he had not required the treatment was rejected because it applied the “but for” test of causation. This was not the correct test. 10 9. The test of causation in workers compensation matters is the “commonsense test” (see Kooragang Cement Pty Ltd v Bates (1994) 35 NSWLR 452 at 463-4; Zinc Corporation Ltd & another v Scarce (1995) 12 NSWCCR 566 at 570-1; Badawi v Nexon Asia Pacific Pty Ltd t/as Commander Australia Pty Ltd [2009] NSWCA 324; 7 DDCR 75). The question was whether, as a matter of commonsense and experience, the second injury resulted from the earlier injury. 10. Applying the “commonsense test” to the causal chain lead to the conclusion that Mr Warwar’s injuries in the motor vehicle accident resulted from the negligence of a third party and not from the first injury. There was no evidence that his employment made any relevant contribution to the car accident. The test that “but for” the first incident Mr Warwar would not have been receiving medical treatment did not establish causation (Sarkis v Summitt Broadway Pty Ltd t/as Sydney City Mitsubishi [2006] NSWCA 358). 11 Lauda Enterprises Pty Ltd v Akkanen [2010] NSWWCCPD 91 Boilermaker’s deafness; whether impairments from separate claims can be aggregated to meet the threshold for compensation for pain and suffering in s 67 of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; s 322 of the Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Roche DP 24 August 2010 Facts: Mr Laurie Akkanen was employed as a builder by the appellant employer, Lauda Enterprises Pty Ltd (Lauda), from 1979 until he retired in February 2006. In the course of his employment, he was exposed to loud noise generated by plant and equipment. Mr Akkanen’s hearing loss resulted from two separate periods of exposure to noise, one up to 1996 and the other up to February 2006. There were two injurious events resulting in two separate claims for compensation for noise induced hearing loss. In 1996 he settled his first claim for an agreed 12% binaural hearing loss (which equalled a 6% WPI after applying the WorkCover Guides). In 2009 he made a further claim for noiseinduced hearing loss assessed at 22% total binaural hearing impairment (which equalled an 11% WPI under Table 9.1). The insurer paid the s 66 compensation due for the additional 5% WPI. The Arbitrator determined that Mr Akkanen had received one injury, namely, boilermaker’s deafness, which resulted in 11% WPI therefore exceeding the threshold in s 67. The Arbitrator awarded Mr Akkanen $8,750 as lump sum compensation in respect of s 67. Lauda disputed Mr Akkanen’s entitlement to s 67 compensation on the ground that he was not entitled to combine the s 66 compensation payments to exceed the s 67 threshold. Held: Arbitrator’s determination confirmed save that paragraph 1 amended to delete Allianz Australia Workers Compensation (NSW) Limited and insert GIO General Ltd; the appellant employer to pay worker’s costs. 1. Lauda submitted that Mr Akkanen’s exposure to noise in the second period up to February 2006 gave rise to a “separate and distinct injury” which had not been addressed by the amendments to the 1998 Act and, as the 1987 Act deemed that there were two injuries, they were to be treated “separately and distinctly” in the absence of an enabling provision such as the repealed s 71 of the 1987 Act. 2. Lauda’s submissions were rejected. The submissions overlooked that the amendments that introduced Chapter 7 to the 1998 Act in January 2002 established a new regime for the assessment of claims for lump sum compensation. Previously workers received compensation for “the loss of a thing”. Post January 2002 workers who suffered an injury resulting in permanent impairment were entitled to compensation for that permanent impairment (s 66(1)). 3. Lauda’s argument ignored the effect of s 322 of the 1998 Act. This section was considered in Department of Juvenile Justice v Edmed [2008] NSWWCCPD 6 at [26] and [27]: “The expression ‘the same injury’ [in s 322(2)] is not defined but it follows that if ‘injury’ in s 322(3) means ‘pathology’ (as it must), then, for the section to be logically consistent, it must mean the same in s 322(2). If ‘injury’ in s 322(2) 12 means ‘pathology’ then, for s 322(2) to be consistent with s 322(3), impairments resulting from the ‘same injury’ (the same pathology) are to be ‘assessed together’ regardless of whether they arise from the same ‘incident’ or separate incidents.” 4. The Commission must read s 322 in the context of the legislation and must have regard to the purpose of the legislation, which is to provide compensation to workers injured in certain defined circumstances (see Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; 194 CLR 355; Wilson v State Rail Authority of New South Wales [2010] NSWCA 198). 5. Mr Akkanen’s impairments resulted from the “same injury” or, as discussed in Edmed, the same pathology or pathological condition, namely, sensorineural hearing loss due to industrial noise. The pathological condition was the same in 2006 as in 1996 even though it resulted from exposure to additional noise. 6. That Mr Akkanen’s injury resulted from two separate periods of noise exposure and was the subject of two separate claims with two deemed dates of injury under s 17 of the 1987 Act did not detract from the fact that he only suffered one injury or pathological condition. It is well established law that a loss can have multiple causes (ACQ Pty Ltd v Cook [2009] HCA 28 at [25] and [27]). 7. The above approach is consistent with Strasburger Enterprises Pty Ltd t/as Quix Food Stores v Serna [2008] NSWCA 354 where it was held, in a case concerning the threshold for injury damages, that an injury and an impairment can have multiple causes. 13 Qantas Airways Limited v Watson (No 3) [2010] NSWWCCPD 86 Reconsideration; s 350(3) Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998 Roche DP 11 August 2010 Facts: Mr Watson received serious injuries in a car accident while returning to the crew hotel while on ‘slip time’ in Los Angeles in February 2005. He had hired a car and visited friends with whom he had a common interest in quarter horses, one hour twenty minutes drive from Los Angeles. His claim for compensation was initially successful. On appeal, Deputy President Bryon revoked the Arbitrator’s decision and made an award for the employer. On appeal to the Court of Appeal, the decision of the Deputy President was set aside: Watson v Qantas Airways Limited [2009] NSWCA 322 (Watson). The Court of Appeal held the Presidential Member had failed to direct himself adequately by reference to Hatzimanolis v ANI Corporation Ltd [1992] HCA 21; 173 CLR 473 (Hatzimanolis). Following further submissions and a rehearing before Deputy President Roche, on 14 April 2010 in Qantas Airways Limited v Watson (No 2) [2010] NSWWCCPD 38 (Qantas No 2), the Arbitrator’s award was revoked and an award made in favour of the employer on the ground that, applying the principles in Hatzimanolis, Mr Watson had not received an injury in the course of or arising out of his employment and, if he had received such an injury, his employment had not been a substantial contributing factor to his injury. Further, Mr Watson had not been injured in circumstances to which s 11 applied. On 28 April 2010, the Court of Appeal delivered judgment in Da Ros v Qantas Airways Ltd [2010] NSWCA 89 (Da Ros). Mr Da Ros received injuries whilst riding a bicycle during a lay over in Los Angeles. Qantas conceded that Mr Da Ros was in the course of his employment at the time of his injury. Deputy President O’Grady made an award in favour of Qantas on the ground that employment had not been a substantial contributing factor. The Court of Appeal held that the Deputy President had erred in his interpretation and application of the phrase “substantial contributing factor” in s 9A of the 1987 Act. Qantas has filed an application for special leave to appeal to the High Court. Based on the Court of Appeal’s decision in Da Ros, Mr Watson sought a reconsideration of the three findings in Qantas No 2 relating to “in the course of employment’, “arising out of” and “substantial contributing factor”. Held: Findings and orders confirmed and respondent worker’s application for reconsideration dismissed 1. There is power in s 350(3) of the 1998 Act, in an appropriate case, for the Commission to reconsider its decision to correct factual or legal errors to do justice between the parties (Maksoudian v J Robins & Sons Pty Ltd [193] NSWCC 36; (1993) 9 NSWCCR 642; Bluescope Logistics Co Pty Ltd (formerly BHP Transport & Logistics Pty Ltd) v Finlow [2006] NSWWCCPD 338). However, the Commission should not lose sight of the general rule that the public interest requires that litigation should not proceed interminably (per Street CJ in Hilliger v Hilliger (1952) 52 SR (NSW) 105 at 108) [16], [17]. 14 2. Mr Watson did not advance any persuasive reason in support of his assertion that the Commission should reverse the factual findings in Qantas No 2. He did not tender any fresh evidence and did not suggest any relevant change in the law. The issues of “in the course of employment” and “arising out of employment’ were not argued in Da Ros. [19] 3. Although there were similarities in Da Ros and Mr Watson’s case, as they were both Qantas employees injured during ‘slip time’ in Los Angeles, there was no similarity between the provision by Qantas of recreational equipment to members of its recreation club (Da Ros), and the hiring by Mr Watson of a car at his own expense to visit friends one hour and twenty minutes from Los Angeles. [22] 4. There is nothing in paragraphs [8] and [22] of Da Ros that, even when read with [58] in Watson, required or even suggested that the Commission should make different factual findings. At [8] of Da Ros, Basten JA observed that the Court of Appeal in Watson “dealt with factual circumstances not dissimilar to the present case” but focused on whether the injury occurred “in the course of” his employment. It was Badawi v Nexon Asia Pacific Pty Ltd t/as Commander Australia Pty Ltd [2009] NSWCA 324; (2009) 7 DDCR 75 which dealt with s 9A, that was “of most direct relevance” in Da Ros. At [22] of Da Ros, Basten JA stated “The activity in which a claimant may be involved when he or she suffers an injury is either within the course of employment or it is not”. That question is a question of fact. [23] 5. In cases of this kind, the test to be applied is the test in Hatzimanolis. Firstly, the period of work has to be characterised and the circumstances of what occurred analysed within that framework. That test was applied in Qantas No 2. [24] 6. The submission that, given the reasoning and facts in Da Ros, the decision in Qantas No 2 on the “arising out of” issue should also be reversed was unsupported by any reasoned argument. There was nothing in Da Ros that required or suggested a different result on the factual question of “arising out of” in Qantas No 2. Da Ros dealt with the application of s 9A in circumstances where Qantas conceded that the injury occurred in the course of the worker’s employment. The Court of Appeal did not consider the “arising out of” issue. [25] 7. The submission that there has been a “quick development” of the law in this area indicated by Da Ros related to the interpretation and application of s 9A, not the issues of “in the course of” or “arising out of”. [26] 8. The submission that the Commission’s decision that Mr Watson was not in the course of his employment “must have been a very close run thing” was unhelpful and did not advance any reason why a different result should have been reached following Da Ros. [28] 9. As there was no basis for reversing the “in the course of” and “arising out of” findings, the “substantial contributing factor” issue did not arise. 15 Rail Corporation New South Wales v Crilly [2010] NSWWCCPD 84 Psychological injury; expert evidence; ss 9A and 11A of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; adequacy of reasons, and disease. Candy ADP 4 August 2010 Facts: Mr Crilly was employed by Rail Corporation NSW. In May 2006 he made a claim for workrelated depression the liability for which was accepted after an initial declinature. In July 2006 he began a gradual return to work. He then suffered a left knee injury for which liability was also accepted. On 18 April 2008, while at home, Mr Crilly was assaulted and suffered facial and head injuries. He was admitted to hospital and later had plastic surgery. He was on leave of various kinds, paid and unpaid, from that time until January 2009. In January 2009 there were various communications between RailCorp and Mr Crilly. On 6 January 2009, Ms Stuardo wrote to Mr Crilly on behalf of the Human Resources Manager, about his absence from work, allegedly without any advice, since 3 January 2009. He was asked to contact Acting General Manager Presentation Services, Mr Jones, by telephone upon receiving the letter in order to discuss his absence from work. The letter finished with this statement: “Failure to do so may result in it being considered that you have abandoned your employment with RailCorp”. Mr Crilly responded to Ms Stuardo’s letter by email, saying he had submitted a medical certificate by email to Mr Le Gallant on Sunday 4 January 2009. RailCorp advised Mr Crilly in a further email that Mr Le Gallant was off duty for medical reasons and other staff were unaware of emails and certificates sent by the worker to him. Mr Crilly responded to the correspondence by emails to various members of RailCorp staff, including the Chief Executive Officer, to whom he complained that he was being “targeted”. He then made a claim for workers compensation on 19 March 2009 nominating the date of injury as 6 January 2009 and describing the injury as; “received letter from RailCorp HR by registered mail threatening to terminate me for ‘abandonment of employment’ for being one day late with medical cert. when it was already supplied”. The injury was said to be “stress/anxiety” and the date of previous similar injury was given as 25 May 2006. Mr Crilly filed an Application to Resolve a Dispute in the Commission. Two dates of injury were specified, namely 15 May 2006 and 23 February 2009. In relation to the first, the particulars of the injury were given as “[d]ue to the nature and conditions of employment from November 2005 to May 2006” and, in relation to the latter date, “the nature and conditions of employment from November 2005 to February 2009”. The injury was described as “Psychological/Psychiatric Injury – Major depressive episode”. He claimed weekly compensation from 23 February 2009 onwards. The Arbitrator found in favour of the worker. The claim for weekly compensation was limited to the period up to 15 December 2009. RailCorp appealed submitting that the Arbitrator has erred in: a) failing to exclude from consideration the report of Dr Canaris on the basis of Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; (2001) 52 NSWLR 705; South Western Sydney Area Health Service v Edmonds [2007] NSWCA 16; 4 DDCR 421 and Hevi Lift (PNG) Ltd v Etherington (2005) 2 DDCR at 271 16 b) finding that the worker had suffered a psychological injury or injuries from which his incapacity for work resulted; c) failing to find that RailCorp had a defence under s 11A of the 1987 Act; d) finding that the provisions of s 9A of the 1987 Act were satisfied; e) finding, in the absence of a claim that his injury was the aggravation, acceleration, exacerbation or deterioration of a disease that the worker had suffered an aggravation, acceleration, exacerbation or deterioration of a disease, and f) failing to give adequate reasons for the findings made. Held: Arbitrator’s decision confirmed. 1. The Arbitrator did not err in declining to exclude Dr Canaris’ report in its entirety. Although Dr Canaris, commented on matters outside his field of professional expertise (the application of s 9A), this did not offend the principles which governed the admissibility of expert evidence as expressed by the NSW Court of Appeal in Makita, Edmonds and Hevi Lift such as to invalidate his opinion based on his professional expertise. The Arbitrator placed no reliance on the expressions of opinion which went beyond the doctor’s professional knowledge and judgment. 2. The evidence established that Mr Crilly suffered a compensable psychological injury in 2006 and was vulnerable to suffer a relapse of that condition which occurred in January 2009. His psychological incapacity resulted from both the 2006 and 2009 injuries. 3. Having made the finding in relation to injury in 2006, the correspondence on 6 January 2009 was not the whole or predominant cause of Mr Crilly’s psychological condition under s 11A. 4. Alternatively, if that was not correct, in considering whether the letter: a) went to retrenchment or dismissal, or b) related to the provision of employment benefits, being the benefits and rights of the worker’s remaining in employment, such as superannuation benefits and the right to challenge the termination of that employment. c) Was a reasonable action by the employer. Held on appeal that: a) Even giving these terms a “wide application” (Davies AJA in Manly Pacific International Hotel Pty Ltd v Doyle (1999) 19 NSWWCCR 181 at [27]), Rail Corp’s submission that the letter was a step in the process of dismissal was rejected. b) The letter related to the worker’s absence without a medical certificate, his failure to resume his duties and the fact that he was not able to be contacted on the telephone numbers of which RailCorp was aware and was not a letter with respect to the provision of employment benefits. c) The sending of the letter on 6 January 2009 and the contents of that letter were not reasonable in all the circumstances. These include the fact that the worker had been absent from work for a considerable time with a head injury and had been known to have had a prior episode of 17 work-related depression. The letter appeared to be premature and unreasonable, given the time at which it was sent, and the confusion on the part of some at RailCorp as to the true state of affairs. The reference to abandonment of employment was unwarranted and unreasonable and appears to have been the matter to which the worker took particular objection. 5. Section 354 of the 1998 Act requires the Commission to act according to “equity, good conscience and the substantial merits of the case without regard to technicalities or legal forms”. Notwithstanding the failure to refer to disease specifically, the parties understood the case was about an aggravation of disease as evidenced by RailCorp’s reliance on the payments of compensation made in 2006 to reduce its liability under s 36 of the 1987 Act. This suggested that RailCorp regarded the events of 2009 as being a continuation of the same injury as that in 2006. 6. The aggravation of the disease of major depression in 2009 was a separate injury. As Hodgson JA said in Murray v Shillingsworth [2006] NSWCA 367; (2006) 4DDCR 313 at [7]: 12. 7. “…I think there may be cases where the question of whether the employment was a substantial contributing factor is affected by whether one considers the work occurrence as an injury simpliciter or as an aggravation of a pre-existing condition. In some case at least, when an injury simpliciter can be considered as having been contributed to by a pre-existing condition, the employment contribution to the aggravation may not be diluted by the pre-existing condition (although the compensation would then be strictly limited to the effects of the aggravation).” The Arbitrator’s reasons were adequate. 18 Haydar Al-Nouri v Al-Nouri Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 85 Section 319 of the 1998 Act; medical dispute; validity of Registrar’s referral of medical dispute to an AMS; status of a MAC following invalid referral; determination of the Commission operating as a res judicata. O’Grady DP 6 August 2010 Facts: Mr Al-Nouri, alleges that he received injury in the course of his employment with Al-Nouri Pty Ltd (‘his own company’). He was employed as a truck driver and his duties were to operate a 12 tonne truck delivering soft drink. The injury alleged was particularised as being injury to “the neck, left shoulder, left elbow, left wrist, upper back, lower back, both legs the left being worst”. The date of the injury was particularised as being the nature and conditions of employment between November 2007 and May 2008. In March 2009 the worker made a claim for lump sum compensation benefits under ss 66 and 67 of the 1987 Act in respect of 18% whole person impairment (‘WPI’) and $15,000 for pain and suffering. The insurer disputed the claim. Mr Al-Nouri filed an Application to Resolve a Dispute. And the respondent filed a Reply. The matter was referred to an AMS, Dr Marsh who issued a MAC on 24 August 2009 in which he assessed a 0% WPI in respect of the neck, back and left leg claims. The claim referred to Dr Marsh had been amended to delete reference to the left upper extremity. The worker did not appeal the MAC under s 327 of the 1998 Act nor did he seek a further medical assessment under s 329 or a reconsideration under s 378 of the 1998 Act prior to issue of the Certificate of Determination. A Certificate of Determination issued, noting that the worker suffered 0% WPI and making no order as to costs. The worker then filed a second Application to Resolve a Dispute in essentially the same terms as the first application. However, that Application contained two significant misstatements: a. denying the worker had been examined at any time by an AMS under Part 7 of Chapter 7 of the 1998 Act, and b. denying proceedings had previously been taken in relation to the injury or any other injury or condition. In filing a Reply to the second Application, the respondent requested the matter be allocated to an arbitrator rather than proceeding directly to an AMS. Despite this request the Commission referred the worker to an AMS. The respondent’s solicitor did not receive notification of the referral. The AMS, Dr Assam, issued a MAC certifying a 12% WPI. That figure was determined having regard to his assessment of 7% WPI cervical spine and 5% WPI lumbar spine. The certificate certified 0% each in respect of the left upper extremity and the left lower extremity. 19 The respondent made an application for reconsideration/review on the basis it had bee denied procedural fairness. The matter was listed before an Arbitrator. The Arbitrator declined to order the Registrar reconsider her decision on the basis he did not have jurisdiction. However he made a finding that the medical referral was made without power due to the operation of s 321(4). Dr Assam’s MAC was found to be a nullity. Further he remitted the matter for referral to another AMS for assessment of the left upper extremity. The worker filed an appeal challenging these orders. Held: Arbitrator’s orders varied on appeal. 1. Agreed with the Arbitrator’s conclusion that the referral to Dr Assem had been made by the Registrar without power but for different reasons. 2. The fundamental question raised on the facts was whether a dispute, being a medical dispute within the meaning of s 319 of the 1998 Act, was in existence at the time of the referral. That question necessarily required an identification of the ‘dispute’ in each application. 3. The dispute in each referral to the AMS was the same, namely a medical dispute within the meaning of s 319 of the 1998 Act concerning WPI resulting from injury to body parts cervical spine, lumbar spine and left lower extremity. 4. The validity of the referral to Dr Marsh was not in question. Dr Marsh’s MAC is conclusively presumed to be correct concerning the matters set forth in s 326(1) which includes the question of the degree of permanent impairment of the worker as the result of the injury. The Certificate of Determination issued by the Registrar reflected the assessments made by Dr Marsh. That determination stands and is binding upon the parties. 5. The Certificate of Determination concluded the dispute which existed between the parties. That determination operates as a res judicata. 6. The effect in law of such determination was in no way lessened or qualified by reason of the existence in the 1998 Act of a power granted to the Registrar to refer a matter for further medical assessment (s 329); nor by the grant of a power to reconsider matters dealt with by the Registrar, an AMS or an Appeal Panel (s 378). As was stated by Neilson J concerning determinations of the former Compensation Court of New South Wales in Bruce v Grocon Ltd [1995] NSWCC 10; (1995) 11 NSWCCR 247 (‘Bruce’): “Of course, the doctrine of res judicata, meaning cause of action estoppel, and also the doctrine of issue estoppel can have no application in a claim for reconsideration pursuant to section 17(4). It is to overcome such principles that the power of reconsideration exists. That is what Rainbow J was referring to in Humphreys v. Shell Co of Australia Ltd. However, in my view, absent an application under section 17(4) of the Compensation Court Act 1984, any determination made by this Court does create an issue estoppel: see Somodaj v. Australian Iron & Steel Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 285. Therefore, there is no reason in principle why a determination of this Court could not in appropriate circumstances create a cause of action estoppel, absent an application under section 17(4).” (at 264) 7. The consequence of the issue of the Certificate of Determination following Dr Marsh’s assessment is that there was no dispute in existence at the time of the commencement 20 of the second set of proceedings concerning such alleged entitlement. There being no dispute there was no power to make the referral to Dr Assem. Any such referral made by the Registrar was ultra vires. The assessment of Dr Assem came into being by reason of an invalid referral and his MAC must be treated as a nullity. 8. Any determination made by the Commission upon reliance of Dr Assem’s MAC would be “infected with the error” which attended the Registrar’s referral (Jopa Pty Limited t/as Tricia's Clip-n-Snip v Edenden [2004] NSWWCCPD 50; (2004) 5 DDCR 321 at [37]). 9. Given Dr Marsh did not asses the left upper extremity, the Arbitrator’s order remitting the matter for AMS assessment of the left upper extremity was confirmed, subject to an order clarifying that the forensic reports relied on by both parties complied with cl 43 of the Regulation. 21 Falee v Harris Farm Markets Pty Ltd [2010] NSWWCCPD 82 Injury; claim for lump sum compensation; referral to Approved Medical Specialist Roche DP 4 August 2010 Facts: Mr Yar Mohammad Falee worked for the respondent employer from December 2005. On 10 January 2006, he injured his back, neck, left shoulder, bowel and liver as a result of lifting boxes of fruit in the course of his employment with the respondent employer. In earlier proceedings Mr Falee recovered compensation for 10 per cent whole person impairment to the lumbar spine (in 2007) and an additional two per cent whole person impairment as a result of injury to his lumbar spine (in 2009). In February 2010, Mr Falee sought hospital and medical expenses, together with compensation for whole person impairment to his lower digestive tract, cervical spine, and to his left upper extremity. These impairments were alleged to have resulted from the incident on 10 January 2006. At the conciliation and arbitration, Mr Falee’s counsel consented to an award being entered for the respondent employer in respect of the alleged injury to the left shoulder, and withdrew the claim for hospital and medical expenses. The respondent employer consented to a claim for whole person impairment in respect of the lower digestive system being referred for assessment by an AMS. The only matter disputed at the arbitration was whether or not Mr Falee had injured his neck. The employer argued that, though the worker complained of upper cervical pain in February 2006, there were no further complaints of cervical pain until September 2008. Radiological evidence in 2008 revealed minor bulging in the lower thoracic region and a cyst at C6/7. The Arbitrator resolved that issue in favour of the employer on the grounds of insufficient evidence to establish even a minor injury to the neck. Held: Arbitrator’s determination revoked; remitted to Registrar for referral to an Approved Medical Specialist for assessment. 1. The respondent employer’s submissions failed to properly address the issue in dispute – being whether Mr Falee injured his neck at work on 10 January 2006. Its submissions went to the consequences of the injury, not its occurrence. There was no dispute that Mr Falee injured his low back and no dispute that he complained of neck symptoms to Dr Salem in early February 2006. Dr Salem’s later report stated Mr Falee’s symptoms arose from his duties. 2. It may be that Mr Falee’s current neck symptoms were due to the cyst at C6/7. However, the issue before the Commission was whether Mr Falee injured his neck while lifting boxes on 10 January 2006. His assertion that he did, was supported by Dr Salem’s clinical notes and report. Dr Salem based his opinion on the nature of the duties undertaken by Mr Falee. Dr Salem’s conclusion was perfectly logical and consistent with the history. It provided a fair climate for the acceptance of the doctor’s conclusion: Paric v John Holland Constructions Pty Ltd [1984] 2 NSWLR 505 at 509-510; (1995) 59 ALJR 844; [1985] HCA 58. That the worker injured his neck was also supported by Dr Stephen, who stated that the worker had not sustained any “significant neck injury”. 22 3. In a case where the only compensation claimed is lump sum compensation, the question of assessment of whole person impairment is exclusively a matter for an AMS: Haroun v Rail Corporation NSW & Ors [2008] NSWCA 192; (2008) 7 DDCR 139. It may be that Mr Falee’s neck symptoms have resulted from the C6/7 cyst. However, as injury is established, the only remaining issue is quantum of the whole person impairment as a result of that injury. 23 Bozinovski v Sydney South West Area Health Service – Fairfield Hospital [2010] NSWWCCPD 89 Failure to give reasons; failure to consider and analyse medical evidence; failure to consider worker’s evidence of continuing symptoms Roche DP 18 August 2010 Facts: The appellant worker, Ms Bozinovski, commenced work with the employer in February 1988 as a full-time cleaner. She developed pain in her neck, arms and shoulders in 2003 or 2004. She had a few weeks off work before she returned on light duties, and then resumed her normal duties. Her symptoms increased and she sought treatment from Dr Aran. In March 2005, Ms Bozinovski slipped at work and experienced neck and back pain. She had a few days off work before returning to work on her normal duties. However, her pain increased and she again saw Dr Aran. In 2007 the pain became “particularly bad”. On 17 October 2007, Ms Bozinovski experienced back and right knee pain whilst mopping at work. Dr Aran certified her unfit for work and she has not returned to work. The employer’s insurer accepted liability and commenced voluntary payments of compensation. On 18 December 2009, the insurer gave notice that it would stop weekly compensation payments on 1 February 2010. The s 54 notice stated that Ms Bozinovski no longer suffered the effects of any injury nor was she incapacitated for work. The notice also stated that employment was “no longer a substantial contributing factor to any injury” to the worker’s “condition”. Ms Bozinovski filed an application with the Commission on 17 February 2010 claiming weekly compensation in the sum of $589.92 from 2 February 2010 to date and continuing. She also claimed hospital and medical expenses in the sum of $4,092.45 and lump sum compensation in the sum of $143,000 in respect of 55 per cent whole person impairment for injuries to the back, neck, right shoulder, left shoulder and left knee. An amendment made to the application deleted the reference to left knee and inserted right knee. The Arbitrator found that Ms Bozinovski injured her back (lumbar spine) and right knee, and that her employment had been a substantial contributing factor to those injuries. The Arbitrator made an award for the respondent employer in respect of the claim for injury to the cervical spine and upper extremities. Ms Bozinovski received an award for s 60 expenses in respect of the lumbar spine and right lower extremity. The Arbitrator found, on the basis of the evidence of Dr Stephenson, that Ms Bozinovski was fit for work without restriction from 17 October 2008. She referred the matter to an Approved Medical Specialist for an assessment of whole person impairment. Ms Bozinovksi lodged an appeal in respect of the findings on incapacity. There was no challenge to the Arbitrator’s finding that she received no injury to her neck or shoulders. Held: Arbitrator’s award in respect of weekly payments revoked; matter remitted to a different Arbitrator for redetermination in accordance with this decision. 1. It is not necessary for a party appealing under s 352 of the 1998 Act to establish error before a Presidential member may intervene (Sapina v Coles Myer Limited [2009] 24 NSWCA 71; 7 DDCR 54). In any event, the Arbitrator erred in her approach and conclusions. [31] 2. The Arbitrator accepted that Ms Bozinovski injured her back and right knee in the course of employment. It was clear the injury was in the nature of aggravation of degenerative changes in the lumbar spine and right knee. The Arbitrator ordered the payment of medical expenses under s 60 without restriction to any particular period indicating that she considered the effect of the injury was continuing. [32] 3. The Arbitrator stated that, based upon Dr Stephenson’s report, the worker had been fit for work without restrictions since 17 October 2008. However, she did not analyse Dr Stephenson’s evidence nor did she give any reason or explanation for accepting it and rejecting other evidence. She did not consider the worker’s evidence of continuing symptoms. The Arbitrator did not refer to the worker’s statement, but merely referred to the medical certificates and medical reports. This did not involve a consideration of the issues. [33]-[34] 4. The Arbitrator repeated the error in the insurer’s s 54 notice of requiring that there be a “substantial connection” between the incapacity and the injury. To succeed in establishing an entitlement to weekly compensation, a worker must establish that his/her incapacity has resulted from the relevant injury. It is not necessary to prove that employment was a substantial contributing factor to the incapacity. 5. The reports of Dr Stephenson were inconsistent. His report of February 2008 supported the worker on injury, incapacity and the need for continuing treatment as he found there was an aggravation of degenerative changes in the lumbar spine and right knee. [36] His October 2008 report stated that he “did not achieve a diagnosis of a musculoskeletal condition”. [43] He had already made a diagnosis: aggravation of degenerative changes. That diagnosis was consistent with the radiological evidence, the commencement of symptoms at work, and the nature of the duties. [53] He did not explain why any aggravation at work had ceased. 6. Matter remitted to a different Arbitrator for redetermination of the extent of any incapacity resulting from the back and right knee injuries. 25 Chhong Heng Taing t/as The Arcade Pharmacy v Gauci [2010] NSWWCCPD 90 Proof of injury; evidence of disease; Part 18 Rule 4(4) of the Workers Compensation Commission Rules 2006, substitution of party to proceedings. O’Grady DP 24 August 2010 Facts: This is the second of two appeals brought by the employer against orders made concerning the worker’s entitlement to a lump sum in respect of whole person impairment (left and right upper extremities) The worker alleged injury in the course of employment on 4 November 2004. The proceedings were initially taken against an entity described as The Arcade Pharmacy Pty Limited. That was a mis-description of the employer and correction of the employer’s title was made by consent many months after the institution of the proceedings. The worker was examined by Dr Harvey-Sutton, an AMS. A MAC issued on 10 December 2008 which certified whole person impairment of 9 per cent. The employer brought an appeal against the assessment by the AMS. The AMS’s findings were confirmed by the appeal panel on 20 March 2009. On 22 April 2009 a Certificate of Determination issued from the Commission making orders concerning payment to the worker of lump sum calculated in accordance with Dr Harvey-Sutton’s MAC. An appeal was brought by the employer against that determination. That appeal (matter A17914/2008) was upheld and the orders made in the determination dated 22 April 2009 were revoked. It was further ordered that the matter be remitted to an Arbitrator for determination of any application the employer may wish to bring pursuant to s 289A(4) of the 1998 Act. That direction enabled the employer to seek leave of the Commission to rely on any previously unnotified matter or matters in its defence of the worker’s claim. The matter subsequently came before an Arbitrator and the subject of the correct description of the employer was raised however was not, at first, resolved. A number of directions were made. The application was the subject of arbitration on 19 February 2010 it was on that occasion that the employer was identified as Mr Taing. By consent Mr Taing was named as the respondent to the application. A certificate of determination was issued on 9 April 2010 which ordered the employer to pay a lump sum calculated in accordance with Dr Harvey-Sutton’s MAC. Held: Arbitrator’s determination confirmed; appellant employer to pay worker’s costs. 1. 2. The employer disputed the Arbitrator’s finding of injury. The employer’s arguments concerning the worker’s credit were rejected. The employer’s argument concerning a suggested “reversal” of the onus of proof concerning the occurrence of injury were rejected. No evidence had been called by the employer to dispute the worker’s evidence concerning a contemporaneous report to the employer of the occurrence of injury. An inference that any evidence from the employer could not have assisted his case was open to the Arbitrator. It was argued by the employer that employment was not a substantial contributing factor to the injury (s 9A). On the review it was found that the Arbitrator correctly concluded that the only evidence concerning causation of injury was that to be found in the expert medical evidence. That evidence established that the injury was received in the course 26 of, and was causally related to, the worker’s employment. There being no other causal factor the inevitable conclusion was that the employment was a substantial contributing factor to injury. 3. The employer placed reliance upon the “disease provisions”. No particular section was identified in submissions as being relevant to this argument. The Arbitrator’s finding that the worker had experienced a “sudden or identifiable pathological change” at the time of injury was confirmed. The employer’s argument that the worker’s condition had, in some way, been aggravated by subsequent employment was rejected. 4. The employer’s complaint on appeal concerning the Arbitrator’s assessment of the evidence of Dr Faithfull was rejected. The employer’s application seeking an adjournment for the purpose of calling Dr Faithfull was refused by the Arbitrator. That refusal was found to be correct for the reasons expressed by the Arbitrator which addressed the nature of the proceedings and the history of the litigation. 5. An argument advanced by the employer that it was not bound by the findings made by Dr Harvey-Sutton in her MAC was rejected. The employer, Mr Taing, took the place of Arcade Pharmacy Pty Limited as the respondent to the worker’s application. The amendment of the description of the employer was not the addition of a new party to the proceedings but rather the substitution, by amendment, of the correct description of the employer for an erroneous description. Such a distinction is addressed by the High Court in Bridge Shipping Pty Limited v Grand Shipping SA [1991] HCA 45; (1991) 173 CLR 231. Part 18, Rule 4(4) of the Workers Compensation Rules 2006 has the effect that the employer, Mr Taing, is, unless an order is otherwise made, bound by any order earlier made in the proceedings. Mr Taing is bound by the presumption that permanent impairment as certified in the MAC is correct (s 326(1)). 27 Mitchell v South West Area Health Service [2010] NSWWCCPD 87 Nature of issues in dispute; whether insurer disputed injury; section 74 Workplace Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998; nature of pathology from injury Roche DP 13 August 2010 Facts: Ms Mitchell worked for the respondent employer from 1986. On 13 October 2005, she slipped and fell on a fire escape stairway. Her evidence was that as she was holding onto the handrail, her foot went from under her and she twisted and fell into the wall. She said she suffered a wrenching injury to her left shoulder, a laceration to her elbow and felt pain in her left leg and knee. On 18 October 2005, she underwent a pre-arranged bone scan for an unrelated condition. The scan revealed a recent fracture to the top of the left fibula. Apart from physiotherapy treatment for her left shoulder, Ms Mitchell had no other treatment and continued her normal duties. In March 2008, Ms Mitchell’s knee condition worsened. Her general practitioner referred her to Dr Nagamori. Ms Mitchell’s knee symptoms continued to worsen and she was diagnosed with a torn meniscus. She underwent an arthroscopy and ultimately a knee replacement operation in 2008. As a result of the operations she was unfit for work from 12 May 2008 to 7 July 2008 and 26 August 2008 until 20 October 2008. On 20 November 2009 Ms Mitchell filed an application in which she claimed lump sum compensation due to the injury to her “left lower limb” together with a claim for weekly payments for the periods she was off work following surgery. The insurer did not dispute injury. The Arbitrator made an award in favour of the respondent in relation to the s 66 claims and the claim for weekly payments. An order was also made that each party pay their own costs of the proceedings. The issue in dispute was the nature of the pathology said to have arisen from the undisputed injury to the left lower limb. Did she tear her meniscus in the fall or did she only fracture her fibula? Held: Arbitrator’s determination revoked; award respondent employer in respect of claim for weekly compensation; claim for WPI remitted to Registrar for referral to AMS; respondent employer to pay worker’s costs. 1. The evidence in the bone scan five days after the fall was consistent with a “recent fracture of the head of the left fibula”. No evidence was called to challenge this opinion. It was held that Ms Mitchell fractured her fibula in the fall. [119] 2. Although later medical histories recorded by the doctors, and Ms Mitchell’s statement, referred to a continuation of knee symptoms from the date of the fall, the first record of complaint regarding knee symptoms was on 14 February 2008. Ms Mitchell had visited her general practitioner on 19 occasions between the date of her fall and the first record of symptoms. Further, Dr Bokor, to whom she had been referred for her shoulder complaints following the fall, did not take a history of knee injury or symptoms. The first referral to Dr Nagamori regarding knee issues was on 3 April 2008 for knee pain “secondary to osteoarthritis”. He recorded a two-week history of “acute knee pain” with 28 “no history of injury”. Therefore, it was not accepted that Ms Mitchell had continuing knee symptoms since the October 2005 fall. [127], [133] 3. Dr Nagamori’s report of August 2008, which referred to the fall and the fractured fibular head, stated that whilst Ms Mitchell did not have ongoing symptoms as a result of the fall, it was possible that a meniscal tear may have occurred at that time. However, a mere possibility is not enough to establish causation on the balance of probabilities. [136] 4. Dr Nagamori’s report also stated that Ms Mitchell’s symptoms seemed only to have appeared in early 2008 making it “somewhat unlikely” that the fall caused the meniscal damage. Given Dr Nagamori’s history of the fall, the fracture and development of knee symptoms in 2008, this provided a “fair climate” for the acceptance of his opinion (Paric v John Holland Constructions Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 58; 59 ALJR 844; [1984] 2 NSWLR 505). Further, as Dr Nagamori was a specialist who was entitled to express an opinion on causation his evidence did not breach the principles discussed in Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; (2001) 52 NSWLR 705. [137] 5. Dr Harrison’s conclusion that, because it was not possible to state that Ms Mitchell’s left knee “condition” was not caused by the accident, the accident was therefore a substantial contributing factor to her current “condition” was rejected. This reversed the onus of proof, which rested on Ms Mitchell. [141] 6. There was no evidence that the fall accelerated the degenerative changes in Ms Mitchell’s left knee. Further, her case was that, as a result of her fall, she suffered a “sequence of on-going problems affecting” her left knee and that the fall was “likely to have resulted in a tear of her medical meniscus”. These scenarios relied on an acceptance on her evidence that she had a continuity of symptoms from the time of the fall until 2008. The evidence did not establish these scenarios. [143] 7. Whether Ms Mitchell has any whole person impairment as a result of the injury to her left lower limb (the fractured head of the left fibula) must be determined by an AMS. 8. The opinions from Drs Harrison and Sullivan were not accepted because they were based on Ms Mitchell’s incorrect history of continuing knee symptoms from the date of the fall. 29 Port Macquarie Hastings Council v Crowe [2010] NSWWCCPD 93 Unreasonable rejection of suitable employment, s 40 (2A) and (2B) of the Workers Compensation Act 1987; ability to earn in suitable employment, s 40(2)(d). O’Grady DP 31 August 2010 Facts: Mr Allan John Crowe, was employed as a park attendant by the appellant council from 1990 until termination of his employment (redundancy) in July 2009. In the course of his employment he injured his right shoulder on a number of occasions and was absent from work for a week in August 2008. Upon his return to work he was provided with full time restricted duties. In December 2008 he communicated to the council his willingness to accept a voluntary redundancy. In March 2009 the council determined that Mr Crowe’s position was to be made redundant. Mr Crowe was informed that the date of separation was to be 2 July 2009. In 2009, before termination of his employment, Mr Crowe suffered two separate aggravations to his right shoulder injury in the course of his restricted duties. Mr Crowe made a claim for weekly compensation in September 2009. The council denied that Mr Crowe suffered ongoing incapacity. It was also asserted that Mr Crowe had unreasonably rejected suitable employment. The Arbitrator found that Mr Crowe’s duties as provided by the council were causing him some distress and that he expected increasing demands to be made upon him at the time he indicated his willingness to accept redundancy. It was found that Mr Crowe’s concerns had led him to seek a voluntary redundancy and that such conduct was not unreasonable. The Arbitrator rejected the council’s argument that it was entitled to rely upon the provisions of s 40(2A). The Arbitrator made a finding of partial incapacity and, following a determination of Mr Crowe’s probable earnings and ability to earn, entered an award in his favour at the maximum relevant statutory rate pursuant to s 40. Held: The Arbitrator’s award of weekly compensation was revoked; an award pursuant to s 40 was entered in favour of Mr Crowe in respect of the period 3 July 2009 to 6 June 2010; matter remitted to another Arbitrator for redetermination of any entitlement to weekly compensation from 7 June 2010; the appellant to pay Mr Crowe’s costs. 1. There was no dispute between the parties as to the occurrence of injury. The Council challenged the Arbitrator’s finding that Mr Crowe’s acceptance of voluntary redundancy was not conduct which constituted unreasonable rejection of suitable employment (s 40(2A)). The council bears the onus of proof concerning those matters relevant to the application s 40(2A). 2. The determination of the question of reasonableness requires an examination of the evidence to ascertain the state of the worker’s knowledge at relevant times (Freightcorp v Duncan [2000] NSW CA 309 per Davies AJA at [19]). Findings were made on review concerning Mr Crowe’s knowledge and state of mind at the date he communicated his willingness to accept redundancy. He had concern about suffering exacerbation of his injuries; he anticipated transfer to a clerical position which he feared and he was concerned about termination of his employment. The Council had failed to prove that Mr Crowe’s rejection of the work provided was unreasonable. 30 3. The council relied upon evidence found in the Intervene reports, vocational and labour availability reports relied upon by the council. It was argued that those reports support the argument that the Arbitrator should have found that, not withstanding injury, Mr Crowe was capable of earning as much, or more, than his probable earnings but for injury. 4. The first report of Intervene was found, on review, to be of no evidentiary value. That conclusion was reached having regard to the statement made in the second report that the earlier report was “incorrect”. A finding was made that the first report had been fabricated. A further finding was made on review that the evidence as to earnings in those occupations nominated by Intervene had no relevance to the question of entitlement to, nor quantification of weekly benefits. 5. Fresh or additional evidence which had been admitted on the appeal established that Mr Crowe, prima facie, had no entitlement to weekly benefits between 7 and 17 June 2010. There was insufficient evidence before the Commission to enable a proper determination of Mr Crowe’s entitlement beyond 7 June 2010. It was appropriate to address the question of the worker’s entitlement up to 6 June 2010, but the matter should be remitted to another Arbitrator for determination of any entitlement Mr Crowe may have to weekly payments from 7 June 2010. 6. It was found that the Arbitrator had not strictly adhered to those steps outlined by the Court of Appeal in Mitchell v Central West Health Service (1997) 14 NSWCCR 527. In the circumstances the evidence concerning entitlement of Mr Crowe required review. 7. The appellant’s argument concerning weekly entitlement focused upon Mr Crowe’s post injury ability to earn. The fresh evidence established that Mr Crowe had apparently secured employment which was more remunerative than his pre-injury employment for a period in June 2010. Proof of that fact is not determinative of the question as to the existence or otherwise of partial incapacity. (Arnotts Snack Products Pty Ltd v Yacob (1984-1985) 155 CLR 171 and Thompson v Armstrong and Royse Pty Ltd (1950) 81 CLR 585). 8. Having regard to the evidence and taking into account those matters provided by s 43A(1) concerning the meaning of “suitable employment” Mr Crowe’s ability to earn in his incapacitated state was found to be the sum of $400 per week. Following application of the relevant steps enunciated in Mitchell an award was entered in favour of Mr Crowe from 3 July 2009 to 6 June 2010. 9. By reason of the presentation of the fresh evidence concerning Mr Crowe’s earnings in June 2010 an order was made remitting the matter to another Arbitrator for determination of any entitlement Mr Crowe may have for weekly compensation from 7 June 2010. 31