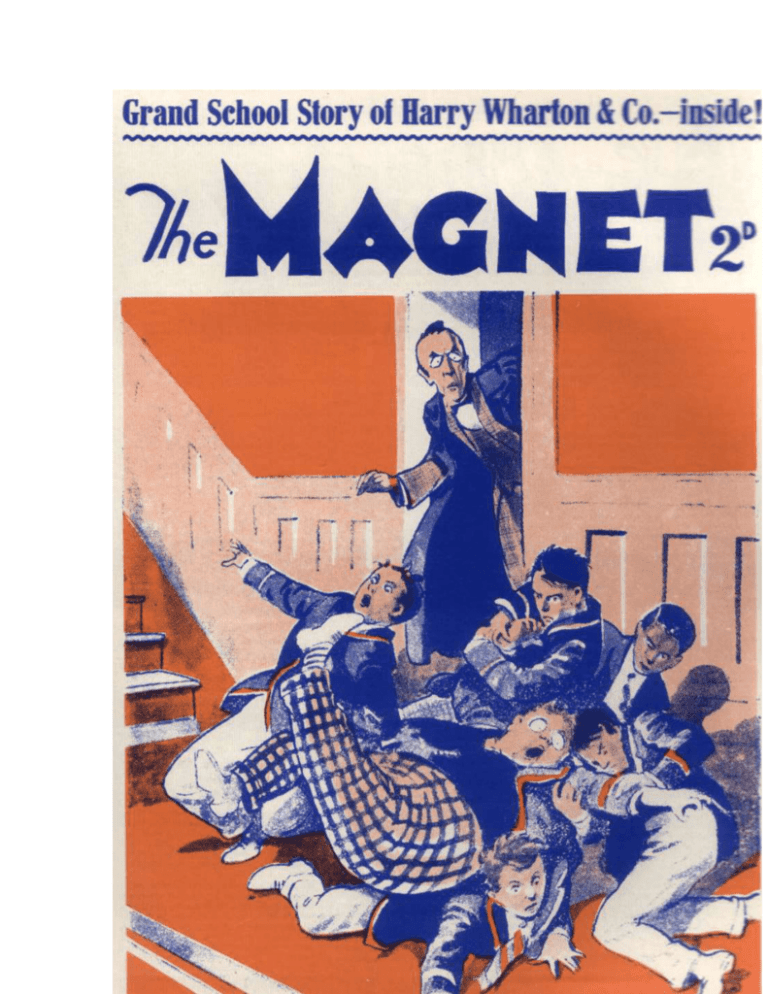

Magnet 1274-B

advertisement