pricing basics

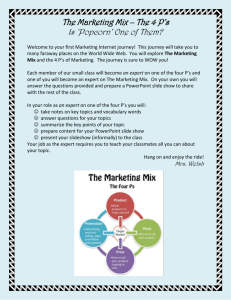

advertisement