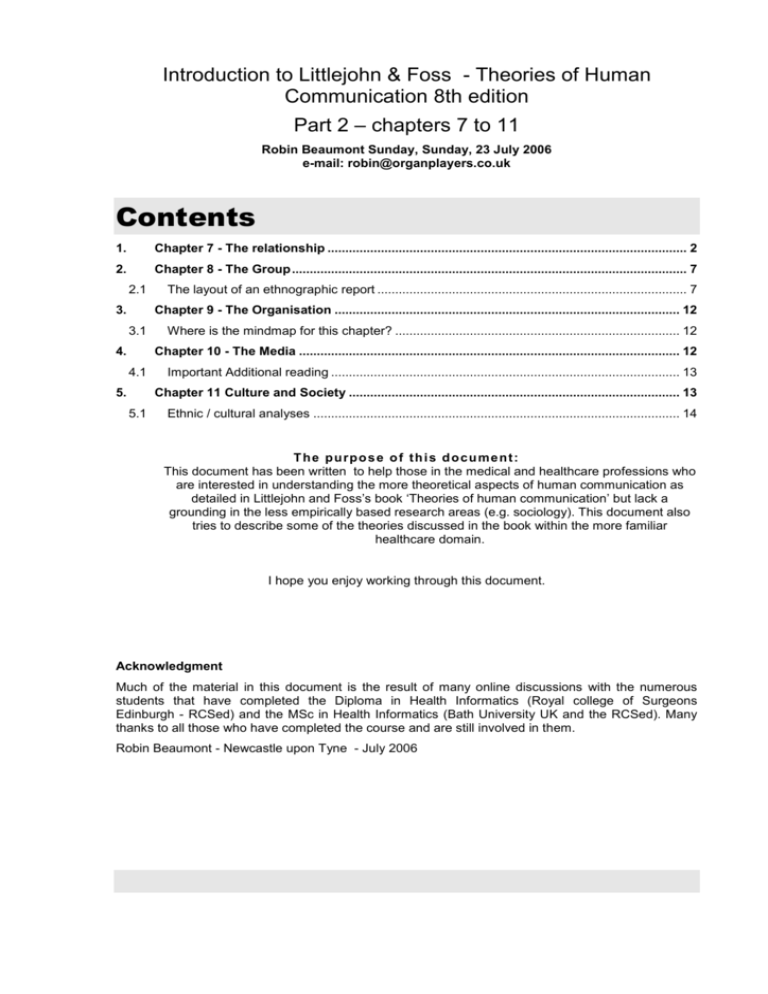

2. Chapter 8

advertisement

Introduction to Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication 8th edition Part 2 – chapters 7 to 11 Robin Beaumont Sunday, Sunday, 23 July 2006 e-mail: robin@organplayers.co.uk Contents 1. Chapter 7 - The relationship ..................................................................................................... 2 2. Chapter 8 - The Group ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1 3. The layout of an ethnographic report ....................................................................................... 7 Chapter 9 - The Organisation ................................................................................................. 12 3.1 4. Where is the mindmap for this chapter? ................................................................................ 12 Chapter 10 - The Media ........................................................................................................... 12 4.1 5. Important Additional reading .................................................................................................. 13 Chapter 11 Culture and Society ............................................................................................. 13 5.1 Ethnic / cultural analyses ....................................................................................................... 14 T he pu rpo s e o f th i s d ocu me nt: This document has been written to help those in the medical and healthcare professions who are interested in understanding the more theoretical aspects of human communication as detailed in Littlejohn and Foss’s book ‘Theories of human communication’ but lack a grounding in the less empirically based research areas (e.g. sociology). This document also tries to describe some of the theories discussed in the book within the more familiar healthcare domain. I hope you enjoy working through this document. Acknowledgment Much of the material in this document is the result of many online discussions with the numerous students that have completed the Diploma in Health Informatics (Royal college of Surgeons Edinburgh - RCSed) and the MSc in Health Informatics (Bath University UK and the RCSed). Many thanks to all those who have completed the course and are still involved in them. Robin Beaumont - Newcastle upon Tyne - July 2006 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 1. Chapter 7 - The relationship This chapter contains much information that at first sight may not appear to be at all useful to you but I think that you may have a different view after the shadowing exercise. Those of you who care for those suffering from chronic conditions will appreciate the various subsections, I worked as a Dialysis nurse at one stage and one of my many duties was to teach home dialysis patients – chronic patients – blur many boundaries – in the ideal patient doctor / nurse relationship and I find that this chapter provides ways of describing the process and understanding why such changes take place. The chapter starts with Watzlawick’s theory which is discussed in less detail than in previous editions which listed her five basic axioms about communication: 1. One cannot communicate (7th edition p235, 8th edition p189 footnote 4) 2. Every conversation no matter how brief, involves two messages – a content message and a relationship message (7th p235) 3. Interactions are always organised into meaningful patterns called punctuation 4. People use both digital and analogue coding. Digital codes are arbitrary, for the sign and the referent, though associated, have no intrinsic relation to each other. The relationship between the sign and the referent is strictly arbitrary (7 th ed. p237). I.e. using bear to designate a large black animal is arbitrary. Being digital you can only say or not say it. Analogic code is different; the sign can resemble to object (i.e. drawings). Most non verbal signs are analogic I.e. facial expressions, emotion in the voice(see 8th ed. chapter 5 p105) 5. Communicators may respond similarly or differently from each other producing symmetrical or complementary relationships (see 8th ed. p190). You can see possibly why they did not bother to include them in the new edition, rather banal, or are they? Anne Fitzpatricks work about family types I find fascinating, you might say again obvious but all the same it helps one understand more clearly why we have a particular attitude towards certain families / people. Those of you who work with families know only too well these types. In English literature various types of family have been scrutinised by many authors, Ivy Compton-Burnett has exposed how the stark, mannered dialogue of her families are revealed as a mask concealing (according to one reviewer writing about her novel “A house and its head”) the abysses of the human personality and its potential for evil! In the theatre Harold Pinter has done much the same thing and interestingly a friend of mine who was lucky enough to meet his family in their house said the experience was just like a Pinter play – right done to the linoleum floor. Previous editions of this chapter contained more information about marriage (5th ed. p271) and conflict management (7th ed. p257). I will fill in some of the gaps below. The families Fitzpatrick studied filled in several other questionnaires besides her own, one of which was the Dyadic Adjustment scale (DAS) to see how they rated compared to a ‘perfect’? marriage. There are other marriage questionnaires around such as the Locke-Wallace Marital Adjustment scale (MAT) and the Family adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale III (also called FACES III) I have not managed to find the actual questionnaires online yet, but have managed to find several papers. As would be expected with research in the Sociopsychological tradition such scales under go a very formalised development method evaluating such things as validity and reliability. One particular aspect they obviously aim for is predictive validity and some of these seem to be fairly high in this area. In fact I’m sure I read somewhere that priests where beginning to use them as part of the premarital assessment. However, with the knowledge that around a third of marriages fail in the UK I would have thought this is not a very good idea if they want to maximise their, and the organists (my!) income. Discussing the various marriage assessment questionnaires, possibly within a cultural context, could be a good discussion board thread? Considering how different males and females communicate, also within the sociopsychological tradition, the famous Cambridge (UK) psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen has helped develop and popularise the concept of the male and female brain possessing different degrees of systemizing and empathising attributes respectively. He has also worked for many years with large number of people suffering from various varieties of Autism and proposes that some types of autism reflect an abnormally excessively male brain (excessive systemizing and very little / no empathising. Alongside questionnaires to assess the level of systemising and empathising Baron-Cohen et al have developed a Friendship and Relationship Questionnaire (FQ) 'to discover whether in social relationships, men and women focused on the other person's feelings or simply on the shared activity . . . They found Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 2 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 that, on average, women are more likely to value empathising in friendships, while men are more likely to value shared interests. Other studies have reported similar results. (p. 35 Baron - Cohen 2004) For more information along with the systemizing and empathising questionnaires see The Essential Difference by Simon Baron-Cohen (2004). This brings us nicely to both Social penetration theory and communication privacy management which both see relationships as being likened to economic transactions. I find the idea of dialectics, of which the second theory is an example, very useful. Baxters dialectical framework (page 201) of integration versus separation; expression versus non-expression and stability versus change along with Rawlins (p210) dialectics seems to succinctly sum up the key areas of struggle in all my friendships / relationships. Make sure you understand the difference between Dialectics (Dialectical) and Dialogue (Dialogic?), by reading page 199 carefully. The section describing friendship in terms of interactional dialectics is very interesting when you apply them to other groups such as the nurse or doctor-patient relationship. This is a long chapter and I felt it did get a little tortuous at times but I did find it interesting and stimulating. Another area that has been lost from this chapter is that of conflict management. I think you might find this interesting given the litigious culture we now live in. ************** Start of abstract (page 257 Littlejohn 7th Edition) ********* An Attribution Theory of Conflict. Recall from Chapter 7 [editors note in 8th ed. chapter 4 page 68 – 72] that attribution theory deals with the ways people infer the causes of behavior. The premise of this approach to conflict is that people develop their own theories to explain the conflicts they are involved with, and these theories are largely a product of their attributions. In other words, how you deal with a conflict depends on how you place blame. Alan Sillars has developed a theory of conflict based on this idea.46 Sillars' theory is included here because it integrates a great deal of mainstream work in conflict communication, codifies many types of conflict behavior, and provides a level of explanation rarely found in conflict theories. According to Sillars, three general strategies of conflict resolution are seen in interpersonal relationships. These include strategies designed to avoid or minimize conflict, those that aim to win in a conflict, and those that attempt to achieve mutual positive outcomes for both parties. Sillars has refined his scheme over the years and refers to these categories simply as avoidance behaviors, competitive behaviors, and co-operative behaviours. Avoidance behaviors employ no communication or, at best, indirect communication. Competitive behaviors involve negative messages, and cooperative behaviors entail more open and positive communication. Table 12.2 [editors note see below] illustrates a variety of strategies found by Sillars in his research.47 As an example of how people use these different strategies in interpersonal conflicts, consider a study by Sillars and his colleagues on conflict in marriage.48 In this study the researchers solicited the cooperation of forty married couples. Each couple was given a kit to take home, consisting of a set of questionnaires for each spouse, a list of ten potential conflict areas, and an audiotape. Each couple was told to answer the questions separately and to seal them in an envelope before proceeding with the rest of the protocol. Then, the couple was to discuss each of the ten topics and to tape their discussions. The topics included such things as work pressures, lack of affection, how to spend leisure time, and child discipline. The couples also completed a marital adjustment scale and Fitzpatrick's measure of marital types (discussed above). One objective of the study was to see how well-adjusted couples in each of Fitzpatrick's categories differed from less well-adjusted couples in their conflict communication. The tape recordings were analyzed in terms of the amount of apparent conflict and the various types of strategies used by the couple in their discussion. The investigators discovered that in all marriage types, more satisfied couples used a more positive tone of voice than less satisfied couples. Separates tended to be avoiders: They maintained a fairly neutral tone and kept their discussions of conflict areas to a minimum. The satisfied separates tended to be even more extreme in this regard. The independents, whether satisfied with their marriage or not, tended to express negative feelings. The more satisfied members of the independent category tended to use more description and self-disclosure than did the less satisfied members of this group. Finally, there was little difference between the satisfied and nonsatisfied traditionals in the sample. Perhaps Sillars' most important contribution is his use of attribution theory to explain conflict behavior. Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 3 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 Recall from Chapter 7 [editor’s note in 8th ed. chapter 4 page 68 – 72] that attributions are inferences made about the causes of behavior. One may make inferences about the causes of some effect, a disposition or trait of another person or oneself, or a predicted outcome of a situation. Whenever people try to explain an event by making inferences, attribution is involved. Sillars believes that in at least three ways attriibutions are important determinants of the definition and outcome of conflicts. First, individuals' attributions in a conflict determine what sorts of strategies they will choose to deal with the conflict. This is true not only because one's reactions and feelings are colored by their attributions but also because future expectations are formed largely as a result of what has gone on in the past. If, for example, you were to see a partner as cooperative, you would probably choose a cooperative strategy, but if you saw this person as competitive, you would probably use a competitive one. Your assessment of responsibility is also important: If you thought you were to blame, you would probably be more cooperative, but if you thought the other communicator were responsible, you would probably be more competitive. Also if you thought your partner had certain negative personality traits, you would be less likely to cooperate. Second, biases in the attribution process discourage the use of integrative strategies. These include a tendency to see others as personally responsible for negative events and to see oneself as merely responding to circumstances. People tend to believe that others cause conflict because of bad intentions, lack of consideration, competitiveness, or inadequacy, but people tend to see their own behavior as merely responding to the provocations of others. Third, the strategy chosen affects the outcome of the conflict. Cooperative strategies encourage integrative solutions and information exchange. Competitive strategies escalate the conflict and may lead to less satisfying solutions. 45 Thomas Steinfatt and Gerald Miller, "Communication in Game Theoretic Models of Conflict," in Perspectives on Communication in Conflict, eds. G. R. Miller and H. Simons (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1974), pp. 14-75. 46 Alan L. Sillars, Stephen F. Coletti, Doug Parry, and Mark A. Rogers, "Coding Verbal Conflict Tactics: Nonverbal and Perceptual Correlates of the 'Avoidance-Distributive-Integrative' Distinction," Human Communication Research 9 (1982): 83-95; Alan L. Sillars, "Attributions and Communication in Roommate Conflicts," Communication Monographs 47 (1980): 180-200; "The Sequential and Distributional Structure of Conflict Interaction as a Function of Attributions Concerning the Locus of Responsibility and Stability of Conflict," in Communication Yearbook 4, ed. D. Nimmo (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1980), pp. 217-236. 47 Alan L. Sillars, Manual for Coding Interpersonal Conflict (unpublished manuscript, Department of Communication, University of Montana, 1986). ************** End of abstract (page 259 Littlejohn 7th Edition) ********* I’m sure you are all very familiar with most of the strategies mentioned in the table on the next page. I always feel it would be interesting to keep a diary for a few days to see which ones I use for particular situations, and then reflection upon the results. The theory seems to say nothing about which are unhealthy and should be avoided or those that are the best to use? Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 4 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 Conflict Management Coding Scheme Conflict Management Coding Scheme From Alan L Sillars et al Communication and conflict in marriage 1983. Table in Littlejohn Theories of human communication 7th ed. page 258 3. Avoidance Behaviors Denial and Equivocation 1. Direct denial. Person explicitly denies a conflict is present. Disclosure. Providing "nonobservable" information: i.e., information about thoughts, feelings, intentions, causes of behavior, or past experience relevant to the issue that the partner would not have the opportunity to observe. 2. Implicit denial. Statements that imply denial by providing a rationale for a denial statement, although the denial is not explicit. 4. Soliciting disclosure. Asking specifically for information concerning the other that the person himself or herself would not have the opportunity to observe (i.e., thoughts, feelings, intentions, causes of behavior, experiences). 3. Evasive remark. Failure to acknowledge or deny the presence of a conflict following a statement or inquiry about the conflict by the partner. 5. Topic Management Conciliatory Remarks 4. Topic shifts. A break in the natural flow of discussion that directs the topic focus away from discussion of the issue as it applies to the immediate parties. Do not count topic shifts that occur after the discussion appears to have reached a natural culmination. 6. Empathy or support. Expressing understanding, support, or acceptance of the other person or commenting on the other's positive characteristics or shared interests, goals, and compatibilities. 5. Topic avoidance. Statements that explicitly terminate the discussion of a conflict issue before it has been fully discussed. 7. Concessions. Statements that express a willingness to change, show flexibility, make concessions, or consider mutually acceptable solutions to conflict. Noncommittal Remarks 6. Abstract remarks. Abstract principles, generalizations, or hypothetical statements. Speaking about the issue on a high level of abstraction. No reference is made to the actual state of affairs between the immediate parties. 7. Noncommittal statements. Statements that neither affirm nor deny the presence of a conflict and that are not evasive replies or topic shifts. 8. Noncommittal questions. Unfocused questions or those that rephrase the questions given by the researcher. 9. Procedural remarks. Procedural statements that supplant discussion of the conflict. Irreverent Remarks 10. Joking. Nonhostile joking that interrupts or supplements serious consideration of the issue. Soliciting criticism. criticism of oneself. Nonhostile questions soliciting 8. Accepting responsibility. Statements that attribute some causality for the problem to oneself. Competitive Behaviors Confrontative Remarks 1. Personal criticism. Stating or implying a negative evaluation of the partner. 2. Rejection. Rejecting the partner's opinions in a way that implies personal rejecting as well as disagreement. 3. Hostile imperatives. Threats, demands, arguments, or other prescriptive statements that implicitly blame the partner and seek change in the partner's behavior. 4. Hostile questioning. Questions that fault or blame the other person. Cooperative Behaviors 5. Hostile joking or sarcasm. Joking or teasing that is used to fault the other person. Analytic Remarks 6. 1. Description. Nonevaluative, nonblaming, factual description of the nature and extent of the problem. 2. Qualification. Discussion explicitly limits the nature and extent of the problem by tying the issue to specific behavioral events. Presumptive attribution. Attributing thoughts, feelings, intentions, and causes to the partner that the partner does not acknowledge. This code is the opposite of "soliciting disclosure." 7. Denial of responsibility. Statements that deny or minimize personal responsibility for the conflict. The section on Carl Rodgers and client centred therapy is new to this edition. You may be wondering why it has been placed in the Phenomenological tradition rather than the Sociopsychological strand. I think the answer is primarily in the techniques used to obtain the data in his work along with the humanistic language he adopted. He relied much more on qualitative techniques than most psychologists and even now often patient centred scoring techniques cause problems when assessed in a quantitative way, often showing very poor inter-rater reliability levels. The chapter ends with a brief introduction to Bubers work, which seems to me to be in the same vein as the Invitational Rhetoric approach discussed in the previous chapter (p175) both approaches which I feel are very important when coming to reflect upon interactions from a more feminine perspective. There is much in this chapter to help you with the shadowing day not only in helping you focus on the shadowees interactions with others but also concerning your interactions with them. Read this chapter very carefully and definitely make sure you do the MCQs for the chapter on the Books web site. Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 5 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 Littlejohn & foss (8th ed.) Chapter 7 - The Relationship Interaction patterns Concensual Cybernetic Symmetrical Relationships Dialogue Disclosure and privacy Schemas and types pluralistic Laissez faire Managing difference 4 types of family Complementary Relationships individuality Knowledge Schemas p.191 Mary Anne Fitzpatrick Relational patterns of interaction Watzlawick p. 189 protective -> seperate emotionally divorced intimacy p.194 Relational Control p. 190 boundaries conversation p. 192 Orientation to communication Sociopsychological conformity p. 192 integration/seperation expression/non expression stability/change Sociocultural Contradictions Social Penetration theory p. 194 Altman & Taylor amplitude salience Change scale sequence pace/rhythum p. 201 Praxis Self disclosure / intimacy (action) Phenomenological Dialectics Baxter p. 199 struggle between various elements in a system Bakhtins Dialogics p. 196 New to the 8th ed. Communication Privacy management p. 203 Sandra Petronio Aesthetic 'being as one' p. 202 turbulance boundary management individual costs / rewards ownership risk Carl rodgers permeability linkage Baber (religious) Applications For you to complete public/private old stuff from previous editions Contextual dialectics Friendships Rawlins (7th ed. p241) ideal/real dependence/independence Interactional dialectics Objective self-awareness "centres on self" "self monitoring" Common uncomfortable state Judgment/acceptance expressiveness/protectiveness Uncertainty reduction theory Low/high information seakers p246 7th ed. affection/instrumentality (utility) Nothing about friendship now! reduced to sentence on p. 210 Subjective self-awareness (centres on self in context) p. 243 7th ed. stuff about self consiousness (now p.66) + self monitors 7th p. 244 gone) Conflict management (7th ed. p255 - 260) Attribution theory Sillars p. 257 (7th ed.) game theory p.255 (7th ed.) Prisoner's dilemma Confess / silent X 2 mixed motive game competitors can either cooperate or compete Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 6 of 15 Avoidance behaviours Competitive behaviours cooperative behaviours Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 2. Chapter 8 - The Group This chapter presents a range of approaches to considering communication in groups, and draws on material from 1910 with Deweys functional theory, up to the present day. I'm sure some of the concepts will be recognisable to you, such as ‘groupthink’. Others I doubt you will have come across; such as Gidden’s Structuration concept I certainly hadn’t. This edition seems to explain Structuration much more clearly than previous editions, at the same time I have now read this numerous times (from the 4th edition onwards) so it might just be persistence!. It is an important area for you to know about for the shadowing exercise. Please note that Structuration is a very different thing to Structuralism, This is important, if anything they are opposites. Made sure you can explain the difference between them in a few sentences. Again this could be done as a group exercise on the discussion board. On a day to day practical level I find Bale's Interaction Process analysis model very useful, simply by remembering that giving, agreeing, storytelling and friendliness are desirable aspects when communicating. The section on Intercultural working is new and I would be interested to know what you think of it? This chapter is really only half the story and you will fill in the gaps in the next chapter which is concerned with organisations. The material I am presenting below would just as easy be presented in chapter 9 and I hope you agree after reading it. 2.1 The layout of an ethnographic report I am sure than most of the journals you are used to dealing with demand a particular layout for articles such as key findings, introduction, data, discussion etc. However ethnographic reports, and remember Littlejohn classes these as similar in nature to phenomenological studies of which you have seem some examples in part one of this introduction, follow very different formats. Unfortunately many of the more traditional journals which have often focused on quantitative reports require the same format for qualitative reports and I'm sure from Paul Willis called Learning to Labour The ethnographic section your knowledge of the fundamental contains the following main sections: propositions document of qualitative /quantitative research you can see the 1. Elements of a culture ridiculousness of this approach. a. Opposition to authority and rejection of the conformist 2. 3. b. The informal group c. Dossing, blagging and wagging d. Having a laff e. Boredom and excitment f. Sexism g. Racism Class and institutional for of a culture a. Class form b. Institutional form Labour power, culture, class and institution a. Official provision b. Continuities c. Jobs d. Arriving We will now consider in detail two examples of layouts of ethnographic studies. Let's look first at a ground breaking study carried out in 1972 -7 on a group of working class boys in Northern England following their transition from school to work. The resulting study was a book by Paul Willis called Learning to Labour: how working class kids get working class jobs first published in 1977 but still available in 2006. He believed that a Marxist lens provided the most helpful mirror to frame his interpretations, looking specifically at the culture of the boys Although the book is divided into two main parts Ethnography and Analysis once you read the book you realise immediately that the terms are used only in a very loose way, new material is presented in the analysis section and the ethnographic section contains much analysis (refection). The table above provides details of the main ethnographic sections. Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 7 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 Taking the typical layout of a small part of the 'Boredom and excitement' subsection illustrated below, you can clearly see the mixture of providing data (quotes or detailed descriptions) and analysis reflections. The actual content of the two pages is provided below. ************** Start of abstract (pages 34-5 Paul Willis Learning to Labour. 1981 Morningside edition. Columbia University Press. New York) ********* Spanksy Joey Coin' down the streets. Vandalising (.. .)that's the opposite of boredom -excitement, defying the Iaw and when you're down The Plough, and you talk to the gaffer, standing by the gaffer, buying drinks and that, knowing that you're 14 and 15 and you're supposed to be 18. The 'laff', talking and marauding misbehaviour are fairly effective but not wholly so in defeating boredom -a boredom increased by their very success at 'playing the system'. The particular excitement and kudos of belonging to 'the lads', comes from more antisocial practices than these. It is these more extreme activities which mark them off most completely both from the 'ear'oles', and from the school. There is a positive joy in fighting, in causing fights through intimidation. in talking about fighting and about the tactics of the whole fight situation. Many important cultural values are expressed through fighting. Masculine hubris, dramatic display. the solidarity of the group, the importance of quick, clear and not over-moral thought, comes out time and again. Attitudes to 'ear'oles' are also expressed clearly and with a surprising degree of precision through physical aggression. Violence and the judgement of violence is the most basic axis of 'the lads' ascendence over the conformists, almost in the way that knowledge is for teachers. In violence there is the fullest if unspecified commitment to a blind or distorted form of revolt. It breaks the conventional tyranny of 'the rule'. It opposes it with machismo. It is the ultimate way of breaking a flow of meanings which are unsatisfactory, imposed from above, or limited by circumstances. It is one way to make the mundane suddenly matter. The usual assumption of the flow of the self from the past to the future is stopped: the dialectic of time is broken. Fights, as accidents and other crises, strand you painfully in 'the now'. Boredom and petty detail disappear. It really does matter how the Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 8 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 next seconds pass. And once experienced, the fear of the fight and the ensuing high as the self safely resumes its journey are addictive. They become permanent possibilities for the alleviation of boredom, and pervasive elements of a masculine style and presence. Joey There's no chivalry or nothing, none of this cobblers you know, it's just . . . if you'm gonna fight, it's savage fighting anyway, so you might as well go all the way and win it completely by having someone else help ya or by winning by the dirtiest methods you can think of, like poking his eyes out or biting his ear and things like this. (. .. .) PW Spike PW Eddie Spanksy PW Joey PW Joey PW Joey What do you think, are there kids in the school here that just wouldn't fight? It gets you mad, like. if you hit somebody and they won't hit you hack. Why? I hate kids like that. Yeah, 'I'm not going to hit you, you'm me friend'. Well, what do you think of that attitude? Id's all accordin'what you got against him, if it's just a trivial thing, like he give you a kick and he wouldn't fight you when it come to a head, but if he's . . . really something mean towards you, like, whether he fights back or not, you still pail him. What do you feel when you're fighting7 (. . .) it's exhilarating, it's like being scared . . . it's the feeling you get afterwards . . . I know what I feel when I'm fighting . . . it's that I've got to kill him, do your utmost best to kill him. Do you actually feel frightened when you're fighting though? Yeah, I shake before I start fighting, I'm really scared, but once you're actually in there, then you start to co-ordinate your thoughts like, it gets better and better and then, if you'm good enough, you beat the geezer. You get him down on the floor and just jump all over his head. It should be noted that despite its destructiveness, anti-social nature and apparent irrationality violence is not completely random, or In any sense the absolute overthrow of social order. Even when directed at outside groups (and thereby, of course. helping to define an 'in-group*) one of the most important aspects of violence is precisely its social meaning within 'the lads" own culture. It marks the last move in, and final validation of, the informal status system. It regulates a kind of 'honour' -displaced, distorted or whatever. The fight is the moment when you are fully tested in the alternative culture. It is disastrous for your informal standing and masculine reputation if you refuse to fight, or perform very amateurishly. Though one of 'the lads' is not necessarily expected to pick fights -it is the 'hard knock' who does this, a respected though often not much liked figure unlikely to be much of a 'laff -he is certainly expected to fight when insulted or intimidated: to be able to 'look after himself, to be 'no slouch', to stop people 'pushing him about'. Amongst the leaders and the most influential -not usually the 'hard knocks' -it is the capacity to fight which settles the final pecking order. It is the not often tested ability to fight which valorises status based usually and interestingly on other grounds: masculine presence, being from a "famous' family, being funny, being good at 'blagging', extensiveness of informal contacts. Violence is recognised, however, as a dangerous and unpredictable final adjudication which must not be allowed to get out of hand between peers. Verbal or symbolic violence is to be preferred, and if a real fight becomes unavoidable the normal social controls and settled system of status and reputation is to be restored as soon as possible: PW Joey (. . .) When was the last fight you had Joey? Two weeks ago . . . about a week ago, on Monday night, this silly ************** End of abstract (pages 34-5 Paul Willis Learning to Labour. 1981 Morningside edition. Columbia University Press. New York) ********* The second example is from Goffman Asylums, which has been mentioned in the fundamental propositions of qualitative / quantitative research document. His 'essay' appears even less structured than that of Willis, not providing a detailed table of contents or index, although this is probably as much to do with the fact that it was produced before word processing! The detailed structure however is very similar to Willis's book, sections of very detailed descriptions / quotes sandwiched between reflections and discussions of similar examples. The extract below is from the introduction. Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 9 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 ************** Start of abstract ********* Erving Goffman Asylums: Essays on the Social Situations of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. 1961 Page 18 -19 Introduction - On the characteristics of total institutions. The handling of many human needs by the bureaucratic Organization - of whole blocks of people -whether or not this is a necessary or effective means of social organization in the circumstances - is the key fact of total institutions. From this follow certain important implications. When persons are moved in blocks, they can be supervised by personnel whose chief activity is not guidance or periodic inspection (as in many employer-employee relations) but rather surveillance -a seeing to it that everyone does what he has been clearly told is required of him, under conditions where one person's infraction is likely to stand out in relief against the visible, constantly examined compliance of the others. Which comes first, the large blocks of managed people, or the small supervisory staff, is not here at issue; the point is that each is made for the other. In total institutions there is a basic split between a large managed group, conveniently called inmates, and a small supervisory staff. Inmates typically live in the institution and have restricted contact with the world outside the walls; staff often operate on an eight-hour day and are socially integrated into the outside world. 2 Each grouping tends to conceive of the other in terms of narrow hostile stereotypes, staff often seeing inmates as bitter, secretive, and untrustworthy, while inmates often see staff as condescending, highhanded, and mean. Staff tends to feel superior and righteous; inmates tend, in some ways at least, to feel inferior, weak, blameworthy, and guilty.3 Social mobility between the two strata is grossly restricted; (social distance is typically great and often formally prescribed. Even talk across the boundaries may be conducted in a special tone of voice, as illustrated in a fictionalized record of an actual sojourn in a mental hospital: 'I tell you what,' said Miss Hart when they were crossing the day- room. 'You do everything Miss Davis says. Don't think about it, just do it. You'll get along all right.' As soon as she heard the name Virginia knew what was terrible about Ward One. Miss Davis. 'Is she the head nurse?' 'And how,' muttered Miss Hart. And then she raised her voice. The nurses had a way of acting as if the patients were unable to hear any-thing that was not shouted. Frequently they said things in normal voices that the ladies were not supposed to hear; if thcy had not been nurses you would have said they frequently talked to themselves. 'A most competent and efficient person, Miss Davis,' announced Miss Hart.4' Although some communication between inmates and the staff guarding them is necessary, one of the guard's functions is the control of communication from inmates to higher staff levels. A student of mental hospitals provides an illustration: Since many of the patients are anxious to see the doctor on his rounds, the attendants must act as mediators between the patients and the physician if the latter is not to be swamped. On Ward 30, it seemed to be generally true that patients without physical symptoms who fell into the two lower privilege groups were almost never permitted to talk to the physician unless Dr Baker himself asked for them. The per-severing, nagging delusional group -who were termed 'worry warts', 'nuisances', 'bird dogs', in the attendants' slang -often tried to break through the attendant-mediator but were always quite summarily dealt with when they tried.5 Just as talk across the boundary is restricted, so, too, is the passage of information, especially information about the staff's plans for inmates. Characteristically, the inmate is excluded from knowledge of the decisions taken regarding his fate. . . . Footnotes 2. The binary character of total institutions was pointed out to me by Gregory Bateson, and has been noted in the literature. See, for example, Lloyd E. Ohlin, Sociology and the Field of Corrections (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1956), pp. 14, 20. In those situations where staff are also required to live in, we may expect staff to feel they are suffering special hard ships and to have brought home to them a status dependency on life on the inside which they did not expect. See Jane Cassels Record, 'The Marine Radioman's Struggle for Status'. American Journal of Sociology, LXII (1957), p.359. 3. For the prison version, see S. Kirson Weinberg. 'Aspects of the Prison's Social Structure', American Journal of Sociology, XLVII (1942), PP. 717-26. 4. Mary Jane Ward, The Snake Pit (New York: New American Library 1955), p. 72. 5. Ivan Belknap, Human Problems of a State Mental Hospital (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1956), p. 177. ************** End of abstract ********* Remember to do the online MCQ at the books website. If anyone is interested I have compiled a number of group work evaluation tools in another document - you will not be questioned on the content in this document; it is simply there as a resource. http://www.robin-beaumont.co.uk/virtualclassroom/chap21/s8/group_working.pdf Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 10 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 Littlejohn & foss (8th ed.) Chapter 8 - The group interpersonal task problems Messages, roles personalitites Environment / system / context interaction Diversity Group structure outputs Group task rew ards self/group Input, process, output model p. 219 Collins & Guetzkow 1964 positive seems friendly assembly effect bonuses synergy individual productivity dramatizes (story telling) agrees Cybernetic gives suggestion give opinion tension decision reduction reintegration gives information asks for information new to 8th. ed. asks for opinion asks for suggestion disagrees shows tension seems unfriendly Bona fide groups Putman & Stohl p. 218 communication evaluation control negative interaction process analysis =human system model robert bales 1970 Dramatizing - relieving tension b y story telling. p216 Idea taken from -> categories: Effective Intercultural Work open Systems approach Oetzel 2001 p. 223 individualism / interact system model collectivism aubrey fisher 1980 p. 221 self-construal (independent / interdependent) Bormann (fantasy theme analysis) actions not divided into task /socioemotional dichotomy "interacts" rather than seperate actions face concerns (self / other / mutual) Sociopsychological 4 phases (p. 222) "The more heterogeneous the group, the harder it will b e to communicate effectively . . ." p. 224 Sociocultural 1. orientation 2. conflict 3. emergence 4. reinforcement Anthony Giddens (originator) marshall scott poole 1985 convergence (agreement) p. 227 standard unitary explains macro - micro process /structure link 3 dimensions decision paths sequences accepts both external forces & intention solution orientated unintended consequences of establishing structures (groupings) that affect future goals (e.g. cleaning makes you = the cleaner also ethnicity) structures action interpretation morality pow er m ediation e.g. one may encourage the development of another, e.g. role structure may result in a new communcations structure etc. interpretation/ understanding 'how ' complex task - process tracks relational contingenies topic focus morality conflict/dialectic proper conduct e.g. equal opportunity p153-4 contradiction pow er 'w hat' objective task 'how ' group task clarity of problem extent of impactexperience group structural characteristics cohesiveness power structure size "Group adopts particular courses etc of action but in so doing creates structures that limit future action" p230 'How w e think' Dew ey 1910 6 steps p. 230 expressing a difficulty defining problem 4 aspects of good group functioning Hirokaw a1988 clear objectives rationalize morality stereotyped (evil, w eak, Irving Janis 1982 stupid outsiders) high group satisfaction but ineffective output direct pressure symptoms p. 232: Groupthink assessment of alternatives bad points analysing problem suggesting solutions illusion of invulnerability understanding of problem self-censorship good points mindguards illusion of unanimity comparing alternatives implementing Concerning Homogeneity, both Oetzel and Janis, have very different things to say about it can the two viewpoints be reconciled? Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 11 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 3. Chapter 9 - The Organisation Most of you will be exposed to one type of organisation or another for the shadowing exercise and this chapter helps you to understand what is happening in a more theoretical manner. However it is important to realise that you are not carrying out an organisational analysis – you primary interest is the shadowee and there perceptions / attitudes / beliefs about the organisation. I think you will find these theories more accessible, the Sociopsychological theories (Weber and Likert) and straightforward and easily applied. Structuration appears once again (giving a hint as to how important it is) in the Sociocultural section. You might find it useful to know that the Organisational Culture subsection has been of use to quite a few students when reflecting upon the shadowing day as others have found the critical theories section. 3.1 Where is the mindmap for this chapter? Because it is important that you really get to grips with the material in this chapter I have left the mindmap for you to do yourself. You might want to start by looking at the mindmap I produced for chapter 14 of the 7th edition - Communication and organisational networks at http://www.robinbeaumont.co.uk/virtualclassroom/chap5/s5/littlejohn/index.htm Remember to do the online MCQ at the books website. Space for your mindmap: 4. Chapter 10 - The Media Personally I find that this chapter seems to lack focus. It starts by discussing Marshall McLuhan and the Global village concept and then moves on to mass communication, rather than discussing various aspects of the global village in detail. Having said that, I did find the sections discussing mass communication very interesting; particularly living in the UK, which seems to be the centre of ‘spin’ nowadays The concept of Dependency theory I also clearly identified with. Unfortunately several of the diagrams and tables from previous editions that helped me to understand some of the material have been removed from the present edition. The chapter is very useful by presenting clear exemplars of the various traditions of theories mentioned in the previous chapters of the book and therefore those of you who had problems with much of the abstract discussions earlier in the book should find that this chapter makes things somewhat clearer for you. Remember to do the online MCQ at the books website. Space for your mindmap: Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 12 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 4.1 Important Additional reading Chapter 10 does not focus on the Web or internet in any great detail. To supplement your reading I would be grateful if you could read through the following two documents. 1. Organisational & confidentiality Issues Learning outcomes (to end of section 3): http://www.robin-beaumont.co.uk/virtualclassroom/chap4/soc1/soc1.pdf 2. This document presents one of the most common metaphors for the modern information age; the Panopticon, and also briefly discusses technological determinism, a similar concept to Dependency theory discussed in Littlejohn's chapter above This document is basically an introduction to the following one. Being Online – The Internet: http://www.robinbeaumont.co.uk/virtualclassroom/chap4/soc3/soc3.pdf This document, like Littlejohn's chapter, starts by discussing Marshall McLuhan but then moves on to consider his ideas in relation to Teleworking and Cyberspace. This is only a very basic introduction to the area; for example, the few paragraphs on e-mail research could have been expanded to fit many chapters. Personally I find these topics very interesting having made the effort to write about them, and have always had a weak spot for Science Fiction. Possibly for one of the residential meetings we should arrange a late night showing of The Matrix or eXistenZ (http://www.haro-online.com/movies/existenz.html ). The book 'The philosopher at the end of the universe' provides an excellent introduction to philosophy by Mark Rowlands via the science fiction film genre. Made sure you do the MCQs in this second document some of them may well appear in the final MCQ test. If you want to learn more about the psychology of the Internet probably one of the better books (based more on research findings than polemic) is Psychology and the Internet by Jayne Gackenbach (ed.) Please note that it is unlikely that much of this material will be of use to you during the shadowing day – you are concentrating on human - human communication, try not to be allured to situations involving electronically mediated communication (EMC) no matter how much you prefer to focus on them in preference to the old fashioned techniques!. 5. Chapter 11 Culture and Society This chapter is new to this edition although nearly all the material was dotted about chapters in the previous edition. This is an important chapter for you particularly the sections concerned with the Phenomenological, Sociocultural and Critical traditions. You should be very familiar with all the theories presented in the first two of these sections, and preferably have read around them if at all possible. Within the semiotic section Bernsteins elaborated and restricted codes are interesting and of use in trying to understand different peoples narrative style. A similar concept was made popular in the late 1950’s in the UK popularised by (Nancy Mitford) ‘U’ and non-U speech to enable people to recognise the upper classes and emulate them. The collection of the original academic article along with several other comments and Mitfords short paper was published as Noblesse Oblige (penguin books, 1956) which also contained several very funny cartoons I have included these as a bit of light relief as another document as I feel you have deserve it by now. Remember to do the Inline MCQ at the books website and if you find it helps create your own mindmap for the chapter. Finally some students have also focused on shadowing someone who is either part of, or working within or is part of an ethnic community, unfortunately Littlejohn provides little in the way of references concerning this topic so I have provided a short list of references below for those of you who decide to go down this interesting route. Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 13 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 5.1 Ethnic / cultural analyses Web sites: The most famous writer at the national level concerning culture is Hoftstede he developed a number of measures to help frame a discussion of culture including: Power Distance Index (PDI), Individualism (IDV), Masculinity (MAS), Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) Long-Term Orientation (LTO) You certainly need to consider these things among others if you are planning on doing a cultural analysis. There is a web site devoted to his work at http://www.geerthofstede.com/geert_hofstede_resources.shtml Other web sites: http://ssr1.uchicago.edu/PRELIMS/Culture/cumisc1.html http://www.itcs.com/elawley/bourdieu.html - Interesting but rather basic http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/in_depth/uk/2002/race/asian_britain.stm Asian Britain: http://www.rdg.ac.uk/econ/workingpapers/emdp432.pdf An excellent reference for telling you something about cultural analysis but the results or his research are poor - shows how useless a questionnaire is in this situation (or possibly it is just a bad questionnaire) "The Interaction Between Culture And Entrepreneurship In London's Immigrant Businesses" this contains a introduction discussing what is culture etc. Books Paul Willis (various reprints) Learning to Labour - is an excellent introduction to how to present ethnographic evidence and reflect upon it. Paul Willis 2000 The ethnographic imagination - policy press Articles: Sheila Scraton 2005 'Bend It Like Patel: Centring 'Race', Ethnicity and Gender in Feminist Analysis of Women's Football in England. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, Vol. 40, No. 1, 71-88 (2005) Ruben G. Rumbaut, 1997. "Assimilation and its Discontents: Between Rhetoric and Reality." International Migration Review. 31 (4). Ruth Frankenberg, 1993. The Social Construction of Whiteness. White Women, Race Matters. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Chapter 7. Bethany Bryson, 1996. "Anything but Heavy Metal": Symbolic Exclusion and Musical Dislikes" American Sociological Review 61 (5): 884-899. Bonnie Erikson, l996. "Culture, Class, and Connections." American Journal of Sociology, 102: 217251. Joane Nagel. 2005?. "Masculinity and Nationalism: Gender and Sexuality in the Making of Nations." Ethnic and Racial Studies. William Julius Wilson, l996. When Work Disappears. The World of the New Urban Poor. New York: Vintage. Chapter. 3. Douglas Massey and Nancy E. Denton, 1993. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 6. Wendy Griswold, l992. "A Methodological Framework for the Sociology of Culture" Sociological Methodology. Elisabeth Long, l997. From Sociology to Cultural Studies. New York: Basil Blackwell. Introduction. Michael Schudson, l997. "Cultural Studies and the Construction of Social Construction: Notes on 'Teddy Bear Patriarchy." Pp. 379-398 in From Sociology to Cultural Studies, edited by Elizabeth Long. New York: Basil Blackwell. Sarah Corse, l997. Nationalism and Literature: The Politics of Culture in Canada and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chapters 1 and 7. Paul DiMaggio, l997. "Culture and Cognition." Annual Review of Sociology. 23:263-87. Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 14 of 15 Littlejohn & Foss - Theories of Human Communication – An introduction - part 2 chapters 7 - 11 Roger Friedland and Robert Alford, 1991. "Bringing Society Back in: Symbols, Practices, and Institutional Contradictions." Pp. 223-62 in The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by W.W. Powell and Paul DiMaggio. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Nicolas Dodier, 1993. "Action as a Combination of Common Worlds." The Sociological Review. 41 (3): 556-71. Michèle Lamont, 1992, Money, Morals, and Manners: The Culture of the French and American UpperMiddle Class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Introduction and conclusion. Also excerpts published in Reading Sociology, Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life, ed. by David N. Newman, Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press, pp. 199-214. Mustafa Emirbayer, l997. "Manifesto for a Relational Sociology." American Journal of Sociology. 103 (2): 281-317. Ewa Morawska, Forthcoming. "Ethnicity as the Double Structure: A Historical-Comparative Approach." Cultural Analysis and Comparative Research in Social History, edited by Willfried Spohn. Opladen: Budrich and Leske. Adrian Favell. 1997. "Citizenship and Immigration: Pathologies of a Progressive Philosophy." New Community 23 (2): 173-195. Aihwa Ong, 1996. "Cultural Citizenship as Subject-Making: Immigrants Negotiate Racial and Cultural Boundaries in the United States." Current Anthropology 37 (5): 737-762. Bonnie L. Mitchell and Joe R. Feagin, 1995. "America's Racial-Ethnic Cultures: Apportion within a Mythical Melting Pot." Pp. 65-86 in Toward the Multicultural University, edited by Benjamin P. Bowser, Tery Jones and Gale Auletta Yougn. Westport: Praeger. Douglas B. Holt, 1997. "Distinction in America? Recovering Bourdieu's Theory of Taste from its Critics." Poetics. 25: 93-120. Ruth Horowitz, 1997. "Barriers and Bridges to Class Mobility and Formation: Ethnographies of Stratification." Sociological Methods and Research. 25 (4): 495-538. Andrea Press, 1994. "The Sociology of Cultural Perception: Notes towards an Emerging Paradigm." Pp. 221-45 in Sociology of Culture: Emerging Theoretical Perspectives, edited by Diana Crane. London: Basil Blackwell. Richard Peterson and Roger Kern, 1996. "Changing Highbrow Taste: From Snob to Omnivore." American Sociological Review. 61: 900-907. End of document Robin Beaumont 08/03/2016 Source: D:\106762522.doc Page 15 of 15