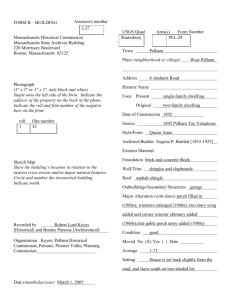

interview with flora adriance

advertisement