bilateral/regional free trade agreements

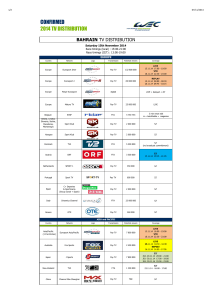

advertisement