The Variety of 'Cottage' Housing in Durham and Norfolk, 1600-1800

advertisement

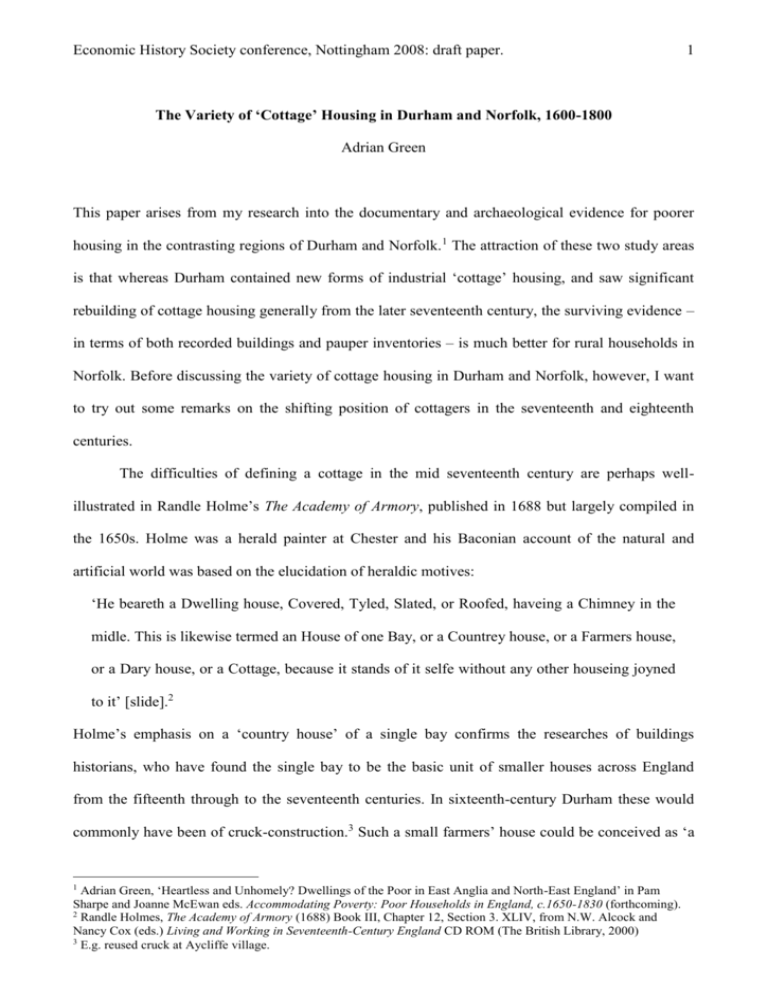

Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 1 The Variety of ‘Cottage’ Housing in Durham and Norfolk, 1600-1800 Adrian Green This paper arises from my research into the documentary and archaeological evidence for poorer housing in the contrasting regions of Durham and Norfolk.1 The attraction of these two study areas is that whereas Durham contained new forms of industrial ‘cottage’ housing, and saw significant rebuilding of cottage housing generally from the later seventeenth century, the surviving evidence – in terms of both recorded buildings and pauper inventories – is much better for rural households in Norfolk. Before discussing the variety of cottage housing in Durham and Norfolk, however, I want to try out some remarks on the shifting position of cottagers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The difficulties of defining a cottage in the mid seventeenth century are perhaps wellillustrated in Randle Holme’s The Academy of Armory, published in 1688 but largely compiled in the 1650s. Holme was a herald painter at Chester and his Baconian account of the natural and artificial world was based on the elucidation of heraldic motives: ‘He beareth a Dwelling house, Covered, Tyled, Slated, or Roofed, haveing a Chimney in the midle. This is likewise termed an House of one Bay, or a Countrey house, or a Farmers house, or a Dary house, or a Cottage, because it stands of it selfe without any other houseing joyned to it’ [slide].2 Holme’s emphasis on a ‘country house’ of a single bay confirms the researches of buildings historians, who have found the single bay to be the basic unit of smaller houses across England from the fifteenth through to the seventeenth centuries. In sixteenth-century Durham these would commonly have been of cruck-construction.3 Such a small farmers’ house could be conceived as ‘a Adrian Green, ‘Heartless and Unhomely? Dwellings of the Poor in East Anglia and North-East England’ in Pam Sharpe and Joanne McEwan eds. Accommodating Poverty: Poor Households in England, c.1650-1830 (forthcoming). 2 Randle Holmes, The Academy of Armory (1688) Book III, Chapter 12, Section 3. XLIV, from N.W. Alcock and Nancy Cox (eds.) Living and Working in Seventeenth-Century England CD ROM (The British Library, 2000) 3 E.g. reused cruck at Aycliffe village. 1 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 2 cottage because it stands of it selfe without any other housing joyned to it’. Like other seventeenthcentury observers, Holmes distinguished a dwelling house from a gentry house: ‘He beareth an Hall, or Mansion House, or a Mannour House, with a Gate house and Walled about; the Roofe Leaded, or Covered, with a Lanthorn on top’ [slide].4 He was, however, somewhat unclear about exactly what a cottage was in the mid seventeenth century: ‘He beareth three Cottages set in triangle, covered. Others term it a Tower between two Cottages’ [slide].5 The only clear reason for distinguishing these buildings as cottages is on grounds of size. Part of the reason for Randle’s confusion is that when he was writing in the mid-seventeenth century, the status of cottages was, I suggest, in a state of flux. This flux related to the transition from manorial copy-hold cottagers with small landholdings to a wage-labour population occupying land-less cottages as ‘sleeping-holes’. The material definition of a cottage was ambiguous to seventeenth-century commentators, since impoverished cottages were not easily distinguished from hovels.6 In the late 1640s in the manor of Auckland in Durham, Nicholas and Thomas Flemming are recorded as having ‘lately erected two poor cottages or sheddes to shelter themselves upon the lord’s waste’.7 If cottagers occupied an awkward space in seventeenth-century educated opinion, then this was a result of their proximity to poverty and the increasing anachronism of customary tenure. In 1600 cottagers with copyhold tenure were generally still a part of manorial society, protected by ‘manorial institutions that strove to protect the interests of and regulate relationships among the tenants of a manor’.8 But manors and customary tenure were a declining force, and equitable relations between landlords and tenants were increasingly framed in relation to commercial valuations of rents and land. In Durham this resulted in a protracted legal dispute between the tenants of the Bishopric estate in Weardale who asserted their ‘tenant-right’ against the introduction 4 Idem. Book III, Chapter 12, Section 3. LVII. Idem. Book III, Chapter 12, Section 3. XLVI. 6 J. H. Bettey, ‘Seventeenth-century squatters’ dwellings: some documentary evidence’ Vernacular Architecture 13 (1982), 28-30: ‘many of the ‘cottages’ referred to in manorial and other documents were in reality no more than huts or hovels. No doubt the first rude dwellings were rapidly replaced by more substantial buildings, but unless that happened the ‘cottages’ referred to in the following extracts would scarcely have lasted more than a few years and would have disappeared, leaving little trace. It is also obvious that the words ‘cottage’ and ‘cottager’ meant something quite different from the meaning they later acquired.’ 7 D. A. Kirby, ed. Parliamentary Surveys of the Bishopric of Durham, Vol. I, Surtees Society, 183, 1968, p. 8. 8 Keith Wrightson, ‘Mutualities and Obligations: Changing Social Relationships in Early Modern England’, Proceedings of the British Academy 139 (2006), 157-94, quoting 165. 5 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 3 of leasehold tenure, while in the industrialising parish of Whickham on Tyneside, smaller copyholders were aggressively disadvantaged by enclosure agreements and those seeking access to coal.9 At the start of the seventeenth century the Whickham ‘cotemen’ were small-holding cottagers, distinguished in manorial records from ‘those holding small-to-medium sized farms’, and the parliamentary survey of 1647 distinguished landholding copy-holders’ from those cottage holdings ‘called the smalls’.10 By the end of the seventeenth century, as Levine and Wrightson have shown, Whickham’s copyholders had undergone ‘gentrification’ as larger holdings were created for commercial farms that fed the industrial workforce. In the mid-later seventeenth century, as coal mining intensified, landless copyholders now had ‘little connection with agriculture beyond the possession of a cow or two, some pigs, or poultry. They included overmen and pitmen, staithemen, wainmen, smiths and vicituallers. Their livings were tied to the coal industry and to the numerous ancillary activities that it had spawned’. At the same time, between the 1630s and 1660s, manorial regulation fell away and Whickham manor court became a land registry from 1666.11 Conditions on the manor of Whickham were perhaps extreme, but seventeenth-century treatises on tenure also found the cottager a problematic category. Advice-manuals, such as Henry Philippes’ The Purchaser’s Pattern (1654), usually focused on the valuation of leasehold land and houses held by contract. The lawyers, many of whom specialised in conveyancing, were clear that cottages added little if any value to land, and copy-hold tenure was largely neglected as an anachronism. This was tackled by Sir Edward Coke in The Compleat Copy-holder (1641), ‘written for the good of Lords and Tenants’, who emphasised that ‘A custome never extendeth to a thing newly created, and therefore a Rent be granted out of Gavell-kind-land, or land in Borough-English, the rent shall descend, according to the course of the Common Law, not according to Custome’. 12 ‘Hence it is that the King himselfe cannot create a perfect Manor at this day, for such things as receive their perfection by the continuance of time, come not within the compasse of a Kings Linda Drury, ‘More Stout than Wise: tenant right in Weardale in the Tudor period’ in David Marcombe (ed.) The Last Principality: politics, religion and society in the bishopric of Durham, 1494-1660 (Studies in Regional and Local History 1, University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education, 1987), 71-100.; David Levine and Keith Wrightson, The Making of an Industrial Society: Whickham 1560-1765 (Oxford, 1991), Chapter 2. 10 Kirby, Parliamentary Surveys, p. 84 cited in Levine and Wrightson, Whickham, p. 140. 11 Levine and Wrightson, p. 140 and 151. 12 Coke, Complete Copy-holder (1641), quoting preface and p. 75. 9 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 4 Prerogative’.13 Samuel Carter, in a Treatise on Copy-hold Estates (1696), cited Coke in Bagnal and Tucker’s Case that ‘the third part of this Realm is in Copy-hold’, but ‘Now we find large and very elaborate Volumes published concerning Estates and Tenures at Common Law, and yet very little hath been professedly written upon this Subject [except by Coke and Mr Calthorp in his Readings], tho’ so great a part of the Lands and Estates of this Nation are protected and preserved by it; which I the more wonder at, for that to know when a Custome is good and allowable in Law requires a more than ordinary skill’. Carter also celebrated the limitations placed on landlords by copy-hold: ‘The Lord may see his power (‘tho moderated) and Tenant may understand his Duty and his Privilege’, ‘But the Lord now is not Enthroned like a Grand Seigniour, whose Proceedings are Arbitary and his Humors Laws; no, he is a mixt Monarch, he is bound up by the Customs and Constitutions of his little Empire’. 14 The tone of landlord-tenant relations expressed in manuals on land law was more equitable up to the Hanoverian succession than it appears thereafter. The appearance of a harsher social regime in the early eighteenth century is evident in the revisions to R. T. Gent’s Tenants-Law. First published in 1670, Gent’s emphasis on the mutual interest of landlords and tenants was altered in eighteenth-century editions of his work, as the additions made to the 1722 edition (reprinted 1737) assume a somewhat more antagonistic relationship between landlords and tenants, and the book was now aimed more emphatically at wealthier-tenant farmers and well-off tenants of houses. This resonates with E. P. Thompson’s world of Whigs and Hunters.15 But on leasehold property at least, landlords had a commercial interest in keeping their tenant-houses, and the cottages of tenants’ workers, in good repair. The Newcastle Courant in 1725 advertised the lease of a farm called ‘Cross-Fines, nigh Houghton-le-Spring’, ‘well-hedg’d, with a dwelling house thereon, and all Out houses convenient’; the farm-labourers lived in ‘six Cottage Houses in good Repair in Houghton aforesaid’.16 This commercial context for housing provides a crucial context for the position and treatment of cottagers. While we should not assume a universally antagonistic relationship between 13 Ibid. pp. 52-3. Samuel Carter, Lex Custumaria: or a Treatise on Copy-hold Estates (1696), pp. 3-4 & 11. 15 E. P. Thompson, Whigs and Hunters: the Origin of the Black Act, (London and New York, 1975) 16 Newcastle Courant 30 January 1725. 14 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 5 landlords and tenants, the bottom line was that cottages on rural estates were not worth enough to alter the value of land. During the early to mid eighteenth century, the marginal economic and legal significance of cottages re-enforced an apparent lack of interest in the lives of cottagers. Only in the later eighteenth century, as Sarah Lloyd, John Crowley and Andrew Ballantyne have recently emphasised, were cottages idealised as a comfortable, homely space, centred on a cheerful hearth.17 Earlier in the eighteenth century they were regarded with greater ambivalence, and there was a remarkable lack of interest in the domestic lives of the poor.18 In the seventeenth century the household was upheld in law, as a ‘man’s house is his castle, and each man’s home is his safest refuge’.19 But this exaltation referred to orderly households, and the poor were separated in conceptions of society that assumed householders were masters in control of subservient members. The domestic life of the poor was irrelevant when concern over household order was focused on the exercise of authority. This marginalisation was underscored in the cursory references to poorer dwellings in documentary sources; those who did not hold houses sheltered in ‘huts’ or ‘hovels’, and even ‘cottages’ – with the marginalisation of customary tenure – signified relative poverty. Gregory King categorised ‘cottagers and paupers’ as decreasing the wealth of the kingdom in 1688.20 A century later, the early-modern patriachal household had been succeeded by a conception of the home as a family domain, with a consequent intensification of interest in domestic life. 21 Concern over the family as the basis of social stability now extended to direct scrutiny of impoverished living conditions. Nathaniel Kent’s Hints to Gentlemen of Landed Property (1775) Sarah Lloyd, ‘Cottage Conversations: Poverty and Manly Independence in Eighteenth-Century England’, Past & Present 184 (2004), pp. 69-108; John Crowley, The Invention of Comfort: Sensibilities and Design in Early Modern Britain and America (Baltimore and London, 2001), pp. 203-229, & ‘From Luxury to Comfort and Back Again: Landscape Architecture and the Cottage in Britain and America’ in Maxine Berg and Elizabeth Eger (eds.), Luxury in the Eighteenth Century: Debates, Desires and Delectable Goods (Basingtoke, 2003), pp. 135-50. Andrew Ballantyne, ‘Joseph Gandy and the politics of rustic charm’ in Barbara Arciszewska and Elizabeth McKellar (eds.), Articulating British Classicism: New Approaches to Eighteenth-century Architecture (Ashgate, 2004), pp. 163-185; 18 See also Adrian Green, ‘Confining the Vernacular: the seventeenth-century origins of a mode of study’ Vernacular Architecture 38 (2007), 1-7. 19 See Lena Cowen Orlin, Private Matters and Public Culture in Post-Reformation England (Cornell University Press, 1994), pp. 2-11, and Christopher Brooks, Law, Politics and Society in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2008), chapter 12. 20 J. Thirsk and J. P. Cooper (eds.), Seventeenth-Century Economic Documents (Oxford, 1972), p. 781. 21 This alteration in ideals was perceived by Lawrence Stone, The Family, Sex and Marriage in England 1500-1800 (London, 1977). See also, Robert B. Shoemaker, Gender in English Society, 1650-1850: The Emergence of Separate Spheres? (Longman, 1998) pp. 15-58. 17 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 6 included ‘Reflections on the great importance of cottages’ – ‘The shattered hovels which half the poor of this kingdom are obliged to put up with, [are] truly affecting to a heart fraught with humanity. Those who condescend to visit these miserable tenements, can testify, that neither health nor decency can be preserved within them’. Optimists in the debate meanwhile emphasised the progress enjoyed by modern Britons, and a paper ‘On the Comforts enjoyed by the Cottagers compared to those of the ancient Britons’ appeared in the Annals of Agriculture in 1797.22 But the general ideal was providing families with the means for self-sufficiency, and it was in this context of family independence that the cottage became idealised as a homely space. Impoverished cottages, by contrast, were increasingly seen as unhomely and ‘heartless’ in the later eighteenth century. The intensification of interest in the home was related to the later eighteenth-century shift in attitudes summarised as the ‘rise in sentiment’. This alteration in sensitivities involved a new recognition of poverty as ‘misery’. The Norfolk parish of Watton’s overseers’ book for 1769-1802 has ‘Alias the Chronicle of Misery’ on its title page.23 This sarcastic comment – unimaginable much before 1769 – also suggests that parish officials were distancing themselves from distress by objectifying the plight of the poor. And I would argue that post-1760 perceptions of unhomely misery and squalor have been carried backwards onto the living conditions of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, without sufficient attention to the experiences of cottagers themselves. Historians’ acceptance that ‘home is where the heart is’ was the preserve of the newly articulated middle class may risk perpetuating assumptions of the desensitizing force of material deprivation.24 It would be unfeeling to underestimate hardship and distress, but it requires an equal lack of empathy to assume that poorer people were unable to find consolation in their own home. In the absence of detailed investigation into the material reality of cottage households, historians have emphasised the testimony of pauper appeals for relief and of later eighteenth - 22 J. L. and Barbara Hammond, The Village Labourer (1911), p. 172. Norfolk Record Office (NRO) PD 218/3. 24 See John Tosh, A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle Class Home in Victorian England (Yale University Press, 1999) pp. 27-50. 23 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 7 century reformers, that housing conditions were both bad and squalid.25 Alternative sources for the materiality of poorer households do not quite accord with remorseless misery. 26 Rather than accepting the notion that poverty prevented people from living in anything but squalor, we should recognise that poorer households generally endeavoured to maintain a homely space. Not everyone succeeded, and the anguish that losing a home created is clearly conveyed in pauper letters. But true squalor – living in filth through the absence of care – did not simply reflect degrees of poverty, or even cultural differences in attitudes to hygiene so much as the psychological problems which arose from a failure to maintain homely space as a refuge from insecurity. Having tentatively set out some thoughts on the overarching context for cottages in this period, we can now turn to the variety of cottage-dwellings on the ground. For those taking up industrial employment in seventeenth-century Durham, the lack of available housing meant temporary to permanent shelters on commons and wastes, invariably described by their employers as ‘hovels’.27 In the Pennine uplands, where lead mining was expanding, the great expanse of Raily Fell was allowed for squatting by lead miners.28 The miners may have made use of the older shieling structures, left available by the decline in farming households relocating to the fells for summer grazing.29 Employers’ strategies for accommodating workers nevertheless generated frictions with established residents. In 1676, complaints at Bishop Wearmouth (i.e. the expanding coal-port of Sunderland) were made of a great influx of poor ‘principally occasioned and incoraged by ye inhabitants thereof in respect of their building and [con]structing diverse small cottage Houses in wch ye sd p[oor] people inhabit wch they Leet and farme’.30 At Chester le Street, coal owners encroached upon the waste to build cottages and ‘unlawfully erected therein certaine new 25 Even the most nuanced historians of poverty have made rather blunt remarks about housing: for example, Thomas Sokoll (ed.), Essex Pauper Letters, 1731-1837 (Records of Social and Economic History, 30; Oxford University Press for The British Academy, 2001), p. 67; Joanna Innes, ‘The State and the Poor: Eighteenth-Century England in European Perspective’ in John Brewer and Echart Hellmuth (eds.), Rethinking Leviathan: The Eighteenth-Century State in Britain and Germany (Oxford University Press for the German Historical Insitute London, 1999), p. 252 n. 67. 26 Alan Mayne and Tim Murray (eds.), The Archaeology of Urban Landscapes: Explorations in Slumland (Cambridge, 2001). 27 Adrian Green ‘Houses and Landscape in Early Industrial County Durham’ in Tom Faulkner, Helen Berry and Jeremy Gregory (eds.), Northern Landscapes: Representations and Realities (Boydell, 2008). 28 An Historical Atlas of County Durham (Durham County Local History Society, 1982), p. 40; Brunskill, ‘Vernacular Architecture in the Northern Pennines’ Northern History 1975, p. 109. 29 Angus Winchester, The Harvest of the Hills: rural life in Northern England the Scottish Borders, 1400-1700 (Edinburgh, 2000). 30 DRO, M7/2, Quarter Sessions, 16 Nov. 1686. Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 8 cottages and placed therein certain ill disposed persons aliens and forinners’.31 The development of more permanent pits led to the formation of pit villages, located away from the established villages, where middling households and farm labourers predominated. Philadelphia Row emerged in the eighteenth century as just such a colliers’ settlement, at the bottom of the bank from the medieval hill-top settlement of Newfield, which contained imposing genteel residences from the early eighteenth century onwards.32 Documentary references to pitmen’s housing perhaps allows us to perceive a distinction between ‘hovel’ and ‘cottage’ by the end of the seventeenth century. Leases record the obligation of the coal-owner to provide tied-housing for the pitmen and a special coal allowance for domestic use. According to Edward Hughes, the ‘obligation of providing ‘hovels’ or dwelling-houses for the pitmen as new pits were opened rested from the first with the coal owner. Indeed, in new areas, it was customary for the owner or leasee to give an allowance ‘for the pitmen’s lodging till houses can be built for them’’. Sir Henry Liddell’s lease of Urpeth colliery in 1712 was to include ‘40s. damage for heap room yearly, and to make ample satisfaction for wayleaves and all spoil ground for building hovels, stables and cottages and all other necessarys for ye Colliery’.33 This implies that the workers were housed around the spoil heaps, which took priority in the efficient movement of coal and its waste. This 1712 lease also distinguishes between ‘hovels’ and ‘cottages’. Whereas ‘hovel’ was a seventeenth-century term for a poorly constructed habitation, by 1700 the term ‘cottage’ implied a somewhat more stable level of income and social standing, although both were occupied by households with only a single-hearth. The ‘hovels’ of the coal-field were probably temporary structures, given that individual coal workings were usually open for a limited period, and the poorest paid members of the colliery workforce were subject to transitory employment and might migrate across the whole of the coal field in the course of their working lives.34 Short-lived colliery ‘hovels’ may have been constructed using similar techniques to those known from 31 M. J. Tillbrook, Apsects of Government and Society of County Durham, 1558-1642, Vol. II unpub. Liverpool University PhD thesis (1981), p. 810. 32 See Green ‘Houses and Landscape’. 33 Edward Hughes, North Country Life in the Eighteenth Century: The North-East, 1700-1750 (Oxford, 1952), p. 257. 34 Levine and Wrightson, Whickham, pp. 189-92. Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 9 excavation of the earliest settlement sites in seventeenth-century America, where posts rammed into the earth obviated the need for foundations.35 The wooden ‘huts’ erected for the pitmen are documented as having brick chimneys for the burning of coal on their single hearths. 36 These perhaps resembled the reconstructed wooden cabins of colonial America [slide].37 Industrial ‘cottage’ housing was not limited to coal and lead mining. More securely employed workers in salt panning and metal manufacture occupied stone cottages, frequently built from the later seventeenth century in rows. At Shotley Bridge, ‘in close proximity to where the first sword factory stood’, a terrace of two-storey cottages on Wood Street (now demolished) were built for the sword cutlers from Solingen in Germany. Two houses had stone door lintels inscribed in German, expressing a commitment to meticulous care in work, and referring to Deutschland and Vaterland, with one dated 1691 [slide].38 Two storeys marked out the households’ economic status, while the inscriptions bore witness to their identity. Industrial terraced housing was initially occupied by those with relatively secure wages, but payments for ‘house rent’ were made by the parish of Pittington to the inhabitants of ‘Pitt Houses’ in 1695 and 1696, presumably for widows and males too old, or ill, to work.39 These terraces provided a rentier income for their genteel owners. Mrs Johnson of Durham advertised ‘Six Salt-Pans at South Shields, with a Mansion House, and other Houses’ in 1723, while Widow Crisp sold ‘ONE Salt Pann, with the Salter’s Houses, and several other Dwelling houses’ in North Shields in 1728, and ‘A Row or Onset of Houses, at the East End of South Shields’ was advertised for sale in the Newcastle Courant in 1729.40 The Salvins (Catholic recusant gentry) of Croxdale Hall near Durham, similarly derived an income from house rents at South Shields.41 But the genteel were not entirely distanced from the industrial work-force, Cary Carson et. al. ‘Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies’ Wintherthur Portfolio 16 (1982), 135-92. 36 N. Emery, ‘Materials and Methods: some aspects of buildings in County Durham’ Durham Archaeological Journal 10 (1994), 113-20. 37 Samuel Chamberlain, Open House in New England (Brattleboro, Vermont, 1937) p. 37 illustrates such a structure at ‘The Pioneers’ Village’, Salem, Massachusetts. 38 Page, Victoria County History of Durham (1905-28) Vol. 2, p. 37. 39 DRO EP Pi/22 v. 129-130. 40 Newcastle Courant 24 May 1729. Salt pans were regularly advertised in the Newcastle Courant during the early to mid eighteenth century, before the industry declined. 41 DRO Salvin papers; DRO D/St/B3/1-4 ‘List of new tenants in Pickering’s house, South Shields’, listing rooms to let in house at Josepth Pickering’s pans and tenement, mid-18C. 35 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 10 and both workers and steward’s housing were in residential propinquity – if not quite cheek-by-jowl – with those paying higher rents or residing in a ‘mansion house’. The relationship of Georgian terraces along Sunderland’s High Street and the terraced cottages on the lanes nearer to the River Wear is illustrated on the Eye Plan of 1785-90 [slide].42 Housing the industrial workforce produced the most dramatic reconfiguration of the County Durham’s settlement pattern since the twelfth century, and many of the nineteenth-century brick-built pit villages originated in late seventeenthand eighteenth-century rows of stone cottages.43 For those occupying better built smaller houses, apparently rebuilt in significant numbers in the late seventeenth century when the value of real wages encouraged a rebuilding by husbandmen and commercial landlords for the industriously employed, 44 the cottage acquired a clearer meaning as a status designation reinforced by the material appearance and small physical size of cottage buildings. It was the process of social polarisation over the late sixteenth to late seventeenth centuries that resulted in a significant proportion of the population occupying ‘cottages’ as a result of dependency on wage labour. These cottages, which make up many of the single-hearth entries in the hearth tax of the late seventeenth century, were often older houses sub-divided. But even where cottagers occupied newly built housing, this was not necessarily an absolute improvement in living conditions. ‘Those families occupying single-room cottages, when in work, in the later seventeenth century may well have had great grandparents in long houses, who raised their own food, a hundred years before.’45 It was the sense that the cottage was a small house, with a household that ought to maintain itself above the threshold of real poverty, which endured to form the basis of a more positive attitude towards the cottage from the later eighteenth century. Cottage was also applied as a term for industrial housing, particularly in semi-rural contexts, such as coal and lead mining, and in rural manufacturing districts. The erosion of customary tenure and common rights, alongside the spread 42 An Eye Plan of Sunderland and Bishopwearmouth 1785-90 by John Rain, reproduced and edited by Michael Clay, Geoffrey Milburn and Stuart Miller (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1984). 43 Green, ‘Houses and Landscape’. 44 Margaret Spufford, The Great Reclothing of Rural England (Cambridge, 1984), p. 3 n. 11; Adrian Green, ‘County Durham at the Restoration: A Social and Economic Case-Study’ in County Durham Hearth Tax Assessment, Lady Day 1666 (British Record Society Index Library, 119, 2006), pp. lxxvii-lxxxix. 45 Quoting Green, ‘County Durham at the Restoration’, p. lxxxviii. Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 11 of wage-labour, deprived the ‘cottager’ of access to land, and arguably turned the cottage into the housing of a rural, as well as an industrial, proletariat. This, however, was an uneven process and cottages on commons and small-holdings remained through to 1800, with some vestige of peasant living traditions. In both Norfolk and Durham the very poor were often on commons; a practice that helped consolidate residential and social segregation, and which the established residents generally tolerated.46 In late seventeenth-century Durham, Bishop Crewe gave permission ‘to ye inhabitants wardons and overseers of ye poor [of] ye manor of Stockton to erect build and sett up … houses for dwellings for poor and impotent persons in any wast or Comons’.47 While at Staindrop the poor were granted their own land, with Raby manor court ordering in October 1690 ‘that none shall make a way through the poores land’.48 There were conflicts between communities over the use of waste and moor by the poor, as when the inhabitants of Ketton in County Durham refused to contribute towards the building of poor huts upon the moor for the poor of Brasserton. 49 But this was a conflict between parishes over paying the cost of providing for another parish’s poor, and there seems to have been general agreement that the waste was the best place for the poor. The accretion of squatter settlement on common land could lead to the formation of permanent settlements, as at Spennymoor (originally an area of moor between medieval settlements) in the Wear Valley.50 More piecemeal occupation of the commons was the norm in Norfolk. In 1710 the Seething manor court admitted Robert Adams and his wife Sarah, with the consent of the rector and inhabitants of Kirstead, to a piece of waste, part of the common pasture of Kirstead, with a cottage 46 Keith Wrightson, 'The 'decline of neighbourliness' revisited'. In Jones, Norman Leslie; Woolf, Daniel R. (ed.), Local Identities in late medieval and early modern England (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), pp. 19-49: manorial institutions ‘excluded those termed “strangers”, “forriners” or “out men” (non-tenants). “inmates” or “byholders (lodgers), “self-hules” (squatters) or “byfires” (cottagers who made illegitimate use of manorial fuel resources). Durham University Library, Weardale Chest, II.44, 26 May 1601, f. 2. ‘On the waste of Auckland, Robert Butter’ built ‘The smithy shop standing upon the Lord’s waste’ and in Weardale Park, ‘divers and sundry intakes have been inclosed and houses lately builded w[i]thin the said fforest’. See also J. Thirsk ed. The Agrarian History of England and Wales, Volume IV, 1500-1640, (Cambridge, 1967), pp. 224-5, for Act of 1550, based on Statutes of Merton and Westminster 1235 and 1285: ‘the improvement of commons and waste ground’ intended to protect small cottagers who built upon the wastes, enabling them to build a tenement and take up to 3 acres. 47 J. Sykes, Local Records, or, Historical Register of Remarkable Events (Newcastle upon Tyne, 1866), p. 101; DRO M7/2, Quarter Sessions 13th July 1681 cited in Matt Greenhall, ‘The Use of Commonal Space as a Sphere of Social Relations in County Durham, 1600-1700’, unpub. Durham University MA Dissertation, 2006, p. 23. 48 DRO, D/Wat Box 61, 23 October 1691. I am again grateful to Matt Greenhall for this reference. 49 DRO, M7/2, Quarter Sessions, 4 July 1675. 50 See J. J. Dodd, The History of the Urban District of Spennymoor (Spennymoor, 1897). Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 12 built on it.51 While at Tasburgh in 1747, the Quarter Sessions authorised the building of a cottage on waste land, the churchwardens and overseers ‘shewing that whereas there are many poor familys and aged and impotent persons belonging to the said parish who are not able to provide Habitations for themselves and praysing that leave might be given to erect a cottage upon some convenient place on the waste, if the Lord of the Manor consenteth thereto’.52 Cottages erected on Norfolk commons might be two storied and well furnished. An inventory from Redenhall with Harleston and Wortewell records ‘Town Goods in ye Possession of Francis Semmons (on ye Common)’ in January 1740. ‘In ye Low Room’ were ‘One Porridge pot, 3 Glass Bottles, 3 Trenchers, one Ovel Table, one Square Table, one Looking-Glass, a Cubbard a Keep, a small Trunk, one Spinning-wheel, a Real, 3 old Chairs, some Tea, Earthen-ware, a Hake, a Hook, a Hatchett, a Sithe, an old Spade’ while ‘Above Stairs’ were ‘One Bed, Bedstead, Bolster, a Rugg, one Blankett and Curtains, 3 pair of Sheets’.53 Semmons’ tools – a hatchet, sythe, and ‘an old spade’ – indicate something of his labouring life, while his wife gained additional income from the spinning-wheel and reel. Semmons’ cottage on the common was reasonably furnished, though like the other 150 pauper inventories I have analysed for Norfolk [see handout table], cubbords, chests, tables and chairs were routinely described by parish appraisors as small and old. Earthenware was ubiquitous, though pewter and wooden vessels also appear, and only a tiny minority of pauper inventories refer to ‘Delft’ or blue-and-white china. Tea-drinking was also universal among pauper cottagers by the mid eighteenth century, and almost all inventories refer to a looking-glass. These were not display items, but small – sometimes broken – pieces of mirror which the poor presumably used to check their appearance before leaving the house. Drinking tea and checking appearances in the mirror were ultimately about ameliorating lives of toil. But signs of cheerfulness are not absent from pauper inventoires. Elias Bygrave at Carrow Abby near Norwich had a ‘Caniva bird and cage’ worth one shilling and six pence in 1754.54 Nor was display absent – Isaac Day in 1742 had a ‘Plate-Rack with six Delf Plates’. Godphrey Goodrum in 1738 occupied just two rooms – a well 51 NRO PD 300/16. NRO PD 297/79. 53 NRO PD 295/102. 54 NRO PD 216/90 Trowse Parish, ‘Caniva bird and cage, 1s. 6 d.’ 1754. 52 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 13 equiped living room and a sleeping chamber: ‘In the Kitching there is 23 Earthen plates and 3 earthen Dishes some pictures; a Dresser with Drawers two Tables 9 Chairs one Boyler and one pot one Hake a pair of hand Irons and tongs; a pair of Spice drawers, a Corner Cubbart with small Earthenwear; two Doz. of Glass Bottles and old Cubbert two Brushes, a Looking Glass plateshelf and a pair of Window Curtains a Killer a pail and old Rubbish. In the Chamber One Bed Bedstead etc. one pair of sheets.55 Elias, Isaac and Godphrey’s luxuries indicate that homely comforts were not exclusively female. Increasingly reliant on the market, pauper inventories demonstrate that a proportion of households enjoyed a degree of homely comfort in the mid to later eighteenth century, But the minority of luxury items that might be taken to signify cheerful endurance are offset by the basic necessities in the majority of inventories. But pauper inventories documenting goods transferred to parish ownership are not a full record of household stuff if prized items were dispersed to real or fictive kin. Family networks of support and the transmission of material assets via inheritance and gift, along with the interventions of employers and friends, made a decisive difference to those who avoided acute poverty. Almost all pauper inventories from Norfolk parishes include ‘a hake’. The Norfolk term for hook, these hakes indicate that cooking was done over the fire, with porridge pots and tea kettles suspended from the hook. This was distinct from the adoption of more complicated cooking technologies by middling households, where cuts of meat rather than single-pot meals, and the adoption of cutlery were increasingly the norm from the later seventeenth century. Single-hearth cottages – invariably of one main living room with a secondary space for sleeping and storage – did in a sense maintain continuities from the seventeenth century – and earlier – in living in a house of one bay, focused on a single hearth. There is, however, very little sign that eighteenth-century cottage households were living in a manner directly similar to the medieval house space centred on an open-hearh. Excavated and surviving buildings indicate that hearths were generally moved to a Both NRO PD 295/102 (11 Dec. 1742, ‘An Inventory taken by Mr James Strange and Mr John Hunt the present Overseers, of Goods in the possession of Isaac Day as follows: First 2 Beds and what belongs thereto one with Curtens, 7 Chairs, 2 Joyn-stools, one Chest of Drawers, one Meal Hutch, 2 small Beer-vessels, 3 Stone Bottles, 3 Tables one Iron Pot, one skillet, 3 wooden Bowls, 6 Trenchers, 5 Glass Bottles, 2 Earthen-Pots, one Dresser, 2 Killers, one Tub, one Pail, one Handle-Cup, two Stone Mugs, two small pans, and one wooden Dish, one Fire-pan, one pair of Tongs, one pair of Cobirons, one Hake, 2 Candlesticks, one Rost iron, 2 pair of Pothooks, one Plate-Rack with 6 Delf Plates, 3 Boxes, 2 Tow Reels, one small Looking-glass, one pair of Bellows, a Childs Chair, two pair of sheets.’) 55 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 14 chimney-wise position – even if they only had rudimentary smoke-hoods – by 1650 if not 1600.56 The mid-seventeenth century is also a key date for alterations in the entrance to smaller ‘cottage’ houses. Adam Longcroft’s analysis of smaller house-plans recorded for seventeenth-century Norfolk, shows that opposed entrances (corresponding to the ‘medieval’ use of space, with the cross-passage at the low-end of the hall) were still common-place in houses constructed between 1600 and 1650, but that after 1650 a lobby-entry arrangement against the chimney was the norm.57 This partly reflects the decisions of commercial landlords – particularly at the Rows in Great Yarmouth, which were built on a speculative basis – but also indicates that householders themselves had pragmatic reasons for departing from customary practice in having an entrance that maximised the space available for furniture and household activities. Eighteenth-century cottagers had too much free-standing furniture – including tables, chairs, cupboards and bedsteads (generally absent from poorer inventories before 1650) – as well as spinning-wheels and laundry tubs – to have an open hearth in the middle of the floor. The evidence from Durham and Norfolk points to a number of conclusions. Local demographic and employment patterns, along with the available housing stock, did much to determine the quality of cottage dwellings. Severe limitations were also placed on where people might provide themselves with shelter without paying rent. The agency of poorer folk lay in their ability to do what they could to maintain the fabric of their cottages. Household efforts were supplemented by direct assistance from the parish and in some instances landlords, who together ensured that the physical fabric of dwellings was maintained, at least among the deserving poor within rural settlements and market towns. Those on the margins of communities were more often in short-lived structures, and cottages on commons might lack proper foundations. Such squatter structures, like encroachment within villages, could be upgraded by succeeding occupants and examples of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century cottages on such sites still stand. Witness this cottage on the common at North Lopham [slide] and another – reputedly the smallest standing pre- Stuart Wrathmell, ‘The vernacular threshold of northern peasant houses’ Vernacular Architecture 15 (1984), 29-33. Adam Longcroft, ‘Plan-forms in smaller post-medieval houses: a case study from Norfolk’ Vernacular Architecture 33 (2002), 34-56. 56 57 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 15 1800 cottage in Norfolk – at the end of North Lopham village street [slide]. For those in regular employment, the late seventeenth century witnessed an improvement in housing and furnishings, as the value of wages and availability of affordable consumer goods increased. This was particularly the case for better paid managerial and skilled members of the industrial workforce on Tyne- and Wear-side – who might have two or even three hearths by the 1660s. 58 In both regions throughout the eighteenth century many households in relative poverty were able to accrue a range of goods beneath a durable roof during their working life and remain in their own homes in old age. There were certainly many less salubrious dwellings in the later seventeenth century, though their exclusion from Hearth Tax lists makes it doubtful whether they counted as households at all. The proportion of those in real poverty almost certainly increased as the eighteenth century progressed, and housing conditions deteriorated where population increased or wages fell. This was the scenario that reformers became alert to across the country from about 1760 and struggled to ameliorate through to 1850. In rural areas there was often considerable continuity in the conditions of the respectable poor, but in urban, industrial and maritime districts conditions worsened as population intensified without adequate sanitation. Farm workers in the estate-villages of Norfolk and the larger commercial farms of Durham experienced an improvement in housing, with tiedcottages rebuilt as an expression of patrician concern. But while sensibilities had altered, the quality of workers’ accommodation was already a commercial consideration in the century before 1760, particularly in the North-East where farmers, salt-pan and coal-pit owners competed for labour. Apparently running against the trend of worsening housing conditions during the eighteenth century, was the widening range of domestic consumer goods available to the poor. But there was no tidy correlation between the qualities of house contents and house fabric, particularly since piecemeal repair became more difficult where the use of traditional materials was curtailed. Records of thatching and piecemeal repair of pauper cottages decline in Norfolk and Durham churchwarden accounts, and the urban-industrial settlements on Tyne-side similarly witnessed a decline in see Adrian Green, ‘The Durham hearth tax: community politics and social relations’, in Barnwell. P.S. & Airs, M (eds.), Houses and the Hearth Tax: the later Stuart house and society (Council for British Archaeology Research Report 150, 2006) pp. 144-154. 58 Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 16 traditional building practices. The rebuilding of Tyne-side’s industrial terraces in the early nineteenth century prompted antiquarian comment. The architect Thomas Bell collected descriptions of Gateshead Fell between 1825 and 1841, including a reference to conditions thirty years ago: ‘At that time, and indeed at a much later period, the cottages were principally of the most miserable description, being built with 'mud' and covered with turf or 'sods', but these have gradually given place to other buildings of a better description and a sod cottage is now a rarity even on Gateshead Fell’.59 The material conditions of poor households referred to in pauper letters compliment the evidence of pauper inventories, which mainly relate to life-cycle poverty. Concern for the deserving poor may have enabled some dignity in old age, and overseers’ accounts in rural parishes often refer to widows with a degree of affection and familiarity. This was distinct from the treatment faced by those in difficulties (supposedly of their own making) during middle age. Already by 1650, there was a distinction between the respectable working poor keeping their heads up and the disrespect of the underemployed, who may have preferred to raise an ale pot. The generations between 1650 and 1850 saw little alteration in this basic division, though the sheer variety of housing occupied by the poor meant this social cleavage was not always clearly reflected in distinctions between dwellings. Those in relative poverty were not always in desperately worse accommodation than the industrious workers whose small houses placed them on the lowest rung of the middling sorts. Many occupied well-constructed housing built for those who could afford higher rents a generation or more earlier. Sub-division of these properties, alongside tiny cottages and the occupancy of lofts and cellars in towns, did create single-room dwelling spaces, though even the smallest of dwellings often had a secondary space for sleeping or storage. Moreover, house size did not uniformly correlate with poverty. Rents certainly forced some of the poor into cramped dwelling spaces, but the contents of the home probably distinguished degrees of poverty more precisely than the outward appearance or 59 Tyne & Wear Archives Service, DT.BEL/4/1 Thomas Bell, Collections relative to the Parish of Gateshead Fell [compiled 1825-1841], quoting p. 28; p. 51 documents William Potts, aged sixty in 1747, as winning stones to build a cottage & 'duffetts' or sods for covering it. Economic History Society conference, Nottingham 2008: draft paper. 17 size of dwellings, since moveable goods were easily pawned, sold or never purchased in times of crisis, while rents were more difficult to negotiate. Posterity should avoid the condescension of assuming that poverty prohibited people from finding consolation at home. Paupers themselves were acutely distressed by the loss of a home. But the very ideas of unhomely misery versus homely comfort are largely a creation of the period under study – emerging in the later-eighteenth and reaching their apogee in the nineteenth century, they have framed understandings of domesticity ever since. Historians’ discovery of an economy of makeshifts that tended to maximise resources, means that assumptions of universal squalor and misery for the poor in their own homes are not sustainable. Misery certainly arose where landlords or employers failed to fulfil patrician values or assistance from family, neighbours and the parish was lacking, but squalor we may suspect was fundamentally a symptom of mental instability. While mental instability may follow from a disrupted domestic economy, many more people coped with material, physical and spatial constraints. There were few, if any, hearth-less houses between 1600 and 1800 and for some of the poorest households we can connect with via documentary and archaeological evidence there are signs of homely comfort. Where this is lacking, and only basic cooking utensils and bedding are recorded, the effort to avoid actual squalor is palpable. Even the most basic of pauper inventories record pewter, wood, or earthenware chamber pots. It is not flippant to conclude that the eighteenth-century poor, when in control of their own dwelling-space, usually had a pot to urinate in. Adrian Green, Durham University Department of History a.g.green@durham.ac.uk