01_Prospectus - WordPress.com

advertisement

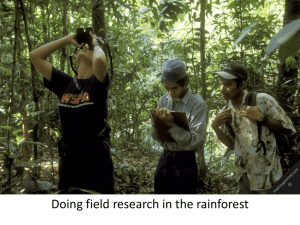

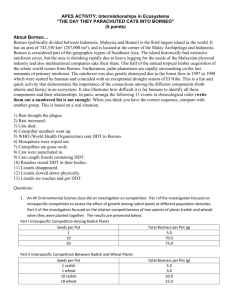

Daniele Cohen Major: Architecture THESIS PROSPECTUS Designing A Patchwork of Abundance A Case Study of the Real World Effectiveness of Sustainable Design Strategies in Two Eco-Tourism Projects in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo Approved: _______________________________________ (ARCH Professor Alison Kwok) Anticipated Completion of Thesis: Fall 2010 Date: _____________ D. Cohen 2 ABSTRACT A growing concern is plaguing the tourism industry: how will it tackle the intricacies of building destinations that are ecologically sustainable, economically viable, and respectful of local culture and heritage?1 In Borneo, an island home to some of the most incredible biodiversity on our planet as well as (unfortunately) some of the most appalling and swift environmental degradation in history, the need to answer these questions is critical. Recently the Eastern Malaysian State of Sabah, located at the northern most tip of the island of Borneo, has produced two compelling solutions to this problem: MESCOT’s Tungog Rainforest Eco-Camp (TREC), and the Borneo Rainforest Lodge (BRL). The following is a two-part analysis of Sabah’s ecotourism industry, with a focus on the facilities mentioned above. First, I will catalogue the various sustainable strategies used by the TREC facility and compile them in a pamphlet that provides detailed but accessible design and construction graphics. My hope is that this document can serve as a guide for communities who are trying to design similar facilities but do not have access to the necessary leadership or expertise. Secondly, I will conduct a quantitative analysis of both facilities, based on the Vital Signs approach2, of the effectiveness of five sustainable strategies employed by both TREC and BRL. Executing tests to compile physical performance data for each method, will allow me to understand how well each strategy is performing in the field. This investigation will also provide me with a metric by which to rank the effectiveness and overall impact of a particular strategy – information that could prove invaluable to the next generation of eco-camps, and Borneo’s design and construction industry in general. “Wild Asia’s Annual Responsible Tourism Award,” Wildasia.org, http://www.wildasia.org/main.cfm/RT_Awards/Enter_RT_Awards (accessed 1 April 2010). 2 Vital Signs has been used as the format for a 5-week project in the Environmental Control Systems course sequence at the University of Oregon for over a decade and was developed by the Agents of Change (for more information see: http://aoc.uoregon.edu/) 1 D. Cohen 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Contextual Investigation……………………………………….…...4-5 II. Partners.…………………………………………………………….5-9 III. Significance………………………………………………………...10-11 IV. Methodology………………………………………………………..11-14 V. Work Schedule……………………………………………………...15 VI. Literature Review…………………………………………………...16-19 VII. Bibliography………………………………………………………...20 VIII. Glossary of Tools, Terms and Acronyms…………………………...21-24 Thank You: To the prospectus class for reading my work so carefully and providing such excellent notes and comments. To my friends, family, and peers who continue to inspire and support me. To Dean Frank for funding this dream of mine and providing me with the opportunity to learn both in Eugene and abroad. To Professor Mitchell for getting me started off on the right foot, and to Professor Levin for her thoughtful revisions. And finally to Alison - my advisor and teacher - thank you for pushing me to do exciting and original research ... I can't wait to see what these next few months bring. D. Cohen 4 I. CONTEXTUAL INVESTIGATION "Tourism ... gets a pass from the media. It is largely ignored by news reporters even though tourism ranks at the very top of global industry and provides one out of every twelve jobs in the world, more than any other single industry." -- Elizabeth Becker, US journalist and author3 To say that Borneo is in the midst of a man made environmental crisis is an understatement. The fact that the world’s third largest island is being ravaged by agricultural and industrial expansion has become old news.4 This is of course by no means a problem endemic to the island; across the globe, very few places remain untouched by the effects of human resource extraction. What makes the conservation effort in Borneo so crucial is its unmatched diversity of flora, fauna and cultural heritage. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), “surveys have found more than 700 species of trees in a 10 hectare plot — a number equal to the total number of tree species in Canada and the United States combined.”5 Further, the WWF states that there are four major threats to Borneo's biodiversity: land conversion, illegal logging, poor forest management, and forest fires. All of these threats are the direct result of a fundamental dilemma in Borneo’s development – namely that it is driven by extractive industries that show no care for the land they destroy or the people and animals they displace and kill in doing so. The island’s soil is so thin that, aside from the cultivation of oil palm, the land is virtually un-farmable. As a means of supporting themselves, much of Borneo’s population has resorted to plundering their island’s natural capital – working as part of the logging, mining or palm oil industries. These businesses support this apparent catch3 ibid Mario Rautner, Raymond J. Alfred and Martin Hardiono, Borneo: Treasure Island at Risk: Status of Forest, Wildlife and related Threats on the Island of Borneo, WWF Germany: Frankfurt am Main © 2005 5 Rhett A. Butler, “Borneo,” Mongabay, http://www.mongabay.com/borneo.html (accessed 10 March 2010) 4 D. Cohen 5 22, exerting control over the people of Borneo based on their own impression that they have no other option. To make matters worse, these industries are rarely sustainable, since little is ever invested in long-term management of resources.6 While it is true that deforested land can be restored, “species that depend on the diversity of old-growth forests for food [and] habitat cannot be replaced,”7and the traumatizing displacement of indigenous peoples creates wounds that are not easily or quickly healed. In order to protect what is remaining and to use forest products in a sustainable manner, providing a livelihood for the people living in the area, a new approach needs to be developed urgently. II. PARTNERS At the forefront of this effort is LEAP – Land Empowerment Animals People – a group that: “trailblazes to discover new ways which provoke sustainable ecological coexistence, in engagement with communities, government, civil society and industry, by building partnerships and collaborations that create mutually transformative processes which seek to balance the needs of all.”8 By partnering with local NGO’s and volunteer groups, as well as the Malaysian and Indonesian governments, LEAP is addressing the need for a new vision of how Borneo’s human population might live in concert with its environment on a number of different levels. Using the metaphor of the spiral as both a model and inspiration, LEAP creates ever lager circles of community, bridging the gaps between ‘fragmented and isolated 6 ibid Rautner, Alfred and Hardiono, Borneo: Treasure Island at Risk, p. 6 8 “Home Page,” LEAP: Land Empowerment Animals People, http://www.leapspiral.org/main.html (accessed 10 January 2010) 7 D. Cohen 6 groups to create unexpected partnerships in the hopes of promoting ‘new understanding and new solutions that serve the greater global community of land, animals and people.’ A strong real world example of the potential of this work is LEAP’s recent partnership with MESCOT (Model for Environmentally Sustainable Community Tourism), in the funding, design and construction of the Tungog Rainforest Eco-Camp (TREC). LEAP served as a consultant securing funding, volunteers and other support for the project from a wide variety of partners including Shell Malaysia, Arcus Foundation, Alexander Abraham Foundation, CREST Planning, Raleigh International, Intrepid Travel, and many other individuals. The MESCOT initiative was formed at the height of the illegal logging era with the aim of relieving pressure on the remaining forest resources, addressing rural poverty in the area and empowering local communities to protect their cultural and natural heritage.9 MESCOT’s chosen vehicle to achieve this comprehensive goal was EcoTourism because it was identified as a means of: 1) Raising income in the poor and remote rural community of Batu Puteh 2) Increasing the economic value of a depleted forest resource 3) Raising funds to support the protection and restoration of the last remaining wetland forests and wildlife of the area. As a result of this refocusing, MESCOT initiatives now fall under the umbrella of the Batu Puteh Community EcoTourism Co-operative (KOPEL), and MESCOT continues its ten year long struggle now under the name: KOPEL-MESCOT. 10 To date, KOPEL-MESCOT has helped create a number of village eco-tourism “Projects and Partnerships: MESCOT Initiative, Tungog Rainforest Eco-Camp (TREC),” LEAP: Land Empowerment Animals People, http://www.leapspiral.org/main.html (accessed 28 March 2010) 10 “ABOUT KOPEL—MESCOT,” MESCOT.org, http://www.mescot.org/KOPEL_MESCOT_About.html (accessed 3 April 2010) 9 D. Cohen 7 associations including the Miso Walai Homestay Program, the Wayon Tokou Nature Guide Association, Tulun Tokou Handicrafts and the Mayo do Talud Boat Service. As previously mentioned, its most recent accomplishment is the Tungog Rainforest EcoCamp. TREC has four key stated objectives: 1. To allow visitors an authentic experience of the sights, sounds and smells of the Borneo rainforest and its indigenous people. 2. To provide a sustainable alternative source of income for the Batu Puteh community as well as an incentive to conserve the remaining rainforest there. 3. To provide a long-term sustainable source of funds for habitat restoration in the surrounding rainforest. 4. To test and implement various technologies and management practices for construction, fuel, water and energy use, waste management, chemical use and visitor behavior to create a model for minimizing the human impact of ecotourism activities. TREC is an innovative community based ecotourism venture, which is unique in its genuine commitment to the preservation of land, animals, and people. Too often “nature based tourism in Sabah is promulgated under the veil of "eco-tourism" but in practice gives little regard to the local population in either social, cultural or economic respects; nor does it take into account aspects such as the sustainable use of fuels, energy or water, the use of chemicals, the disposing of waste products, or the behavior and management of visitors and their impacts on sensitive sites.”11 The Tungog Rainforest Eco-Camp aims to reverse this trend, and set “a bench-mark for the implementation of available technology and management practices that can reduce visitor's negative impacts and enhance their positive benefits to natural resource management and conservation.”12 Relying on manual labor to minimize pollution and disturbance to the forest, skilled craftsmen from the local community constructed the Eco-Camp using indigenous “Tungog Rainforest Eco-camp,” MESCOT.org, http://www.mescot.org/TREC-Project_Update.html (accessed 3 April 2010) 12 ibid 11 D. Cohen 8 techniques and local building materials. In addition, the camp utilizes ecologically sustainable technologies including composting toilets and sealed reed beds for treating waste, tanks to capture and recycle rainwater, gravity and solar powered water systems, and a zero chemical-use policy.13 Accommodations are simple open-air tent platforms bolted together for easy removal with no concrete footings and no lasting footprint. TREC represents a modern interpretation of the ‘leave no trace’ style of architecture produced by the indigenous people of Borneo for centuries. My decision to study this particular project is primarily a result of its commitment to both the traditional material palette and construction practices (manual not machine labor) employed in its assembly. It is important to note here that architects have a long history of romanticizing indigenous architecture as always being environmentally friendly. While it is true that many “primitive” societies have developed effective architectural strategies to take advantage of the intricacies of their particular climate, it has also been shown that modern high performance construction can achieve similar if not better performance if executed correctly. In light of this, the second project I have chosen to examine, the Borneo Rainforest Lodge (BRL), shares a mission similar to TREC – namely creating a bridge between conservation research and tourism while boosting local industry – but employs a distinctly modern methodology to achieve it. Comparison of these two projects will hopefully add some substance – particularly in the form of quantitative data – to the debate over which typology is more sustainable. “Projects and Partnerships: MESCOT Initiative, Tungog Rainforest Eco-Camp (TREC),” (accessed 28 March 2010). 13 D. Cohen 9 The BRL is a more traditional “eco-appreciation” lodge, which unlike TREC, does not provide any opportunities for tourists to give back directly to the forest restoration or wildlife conservation effort. Instead, the “rustic international-standard lodge built beside the Danum River”14 provides ample opportunities for guests to explore the incredible diversity and complexity of the rainforest with guided jungle walks, bird watching, canopy walks and night safaris. A small part of the lodge’s fee funds onsite research conducted by a rotating group of scientists. Recently remodeled by Ian Hall of Arkitrek15, the BRL is a compelling combination of modern building technology and traditional design sensibility. Cleverly designed to maximize benefits of natural breezes and minimize the effect of direct sunshine, the design makes use of exhaust fans, industrial windows, doors and trusses, metal roofing, mineral wool insulation, concrete block as thermal mass and high performance paints and finishes. By developing a performance baseline to compare the effectiveness of these contemporary strategies and building techniques vs. TREC’s more ‘traditional’ ones, my investigation will address “previous limitations in the conceptualization of our professions ‘romantic’ attitude about traditional or neo-traditional architecture.”16 While claims about the sustainability of aboriginal architecture are common, little environmental performance testing has actually been performed. The intention of my research is to remedy this deficiency in some small way. “Home Page,” Danum Valley Borneo Rainforest Lodge, http://borneorainforestlodge.com/index.htm (accessed 15 April 2010) 15 In addition to my thesis research I will be working with Ian on the design of two conservation facilities, for the Sun Bear and the Sumatran Rhino respectively 16 Ihab Elzeyadi, “A Tale of Two Houses: Environmental Quality, Sustainability, and Indoor Comfort Inside Hassan Fathy's Mit Rehan And A Contemporary Villa in Cairo, Egypt,” Vital Signs Case Study, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 1996, http://arch.ced.berkeley.edu/vitalsigns/bld/Casestudies/Abstracts/uwm_twohouse_ab.html 14 D. Cohen 10 III. SIGNIFICANCE “A knowledge base and research infrastructure are essential to support the expertise and creativity required to improve the quality of life through the design of inspiring buildings and sustainable communities and environments.” –Donald Watson, Architectural Research Quarterly, 1999 Unlike many other rainforest regions, Borneo’s rural population with its demand for agricultural land and other resources is not the main perpetrator of the island’s worrying deforestation. The problem, as discussed in the introduction, is an economy based on exportation – which in this case may as well be a synonym for exploitation. As evidenced by the success of TREC and the BRL, tourism is the industry that is perfectly poised to turn this trend around and begin to foster a culture that values community, good craftsmanship, appropriate scale, and right livelihood. I hope that in documenting, analyzing and comparing the TREC and BRL projects, I can further illuminate eco-tourisms potential as a catalyst for disseminating sustainable community oriented design. As stated in the abstract, this investigation will provide me with a metric by which to rank the effectiveness and overall impact of a particular strategy – information that could prove invaluable to the next generation of eco-camps and Borneo’s design and construction industry in general. Furthermore, real world performance data on the effectiveness of sustainability strategies can be applied everywhere, and is greatly desired by architects worldwide who want to better understand the systems they are dealing with. Lastly, the issue of incorporating development, sustainability, and culture is especially relevant in our world today. The spread of monoculture and resource extraction to support a growing world economy continues to cause widespread ecological D. Cohen 11 degradation that in turn impoverishes anyone living off the land it claims and drives them into urban environments where nearly always, they lose touch with their traditions and customary ways of life. This depressing trend can be turned around with a rigorous understanding of both the processes and effects of sustainable design – especially as it applies to eco-tourism, which is something this research aims to provide. Developing an architectural typology that supports a delicately woven patchwork of animal and human habitat, and that fosters an inextricable connection to the land can potentially support an ethos that is respectful of the earth, and mindful of our responsibility to posterity. It is my hope that I can contribute to the vision of what that future patchwork might look like – and offer my findings as a feasible alternative to the destruction we seem to believe is the only way to sustain a large population on the island today. IV. METHODOLOGY The purpose of this case study is twofold: 1) Document the sustainable strategies employed by the TREC project, creating a pamphlet that illuminates the construction process and operation of these strategies with clear and concise graphics and text, so that it can be used as an accessible precedent for other communities with similar goals; 2) Identify five environmental issues that both TREC and the BRL address with specific sustainable strategies, and test these strategies using the Vital Signs method to determine if they are operating as intended as well as which strategies are most effective.17 Slightly different methodologies, requiring particular measurement tools and a 17 For information regarding the tools and terms in this section see the glossary at the end of the prospectus D. Cohen 12 unique analysis approach will be needed to test each strategy. Covering all of the testing methods and equipment employed in this project is beyond the scope of this prospectus. Instead, I have included one example (testing and comparing the efficiency of ventilation strategies in the “traditional” TREC and the “modern” BRL facilities) below. My tentative hypothesis for this section is that the BRL’s combination of ventilating floors and walls, movable screens, exhaust fans, and highly insulated roof will outperform TREC’s traditional strategy. I will be working to define “outperform” in specific testable terms: does it mean increased airflow? Decreased airflow? Regulated airflow? And, if the aim is stable daily temperature stratification for maximum occupant comfort, how does that difference in airflow affect the indoor temperature and humidity? Answering these questions will allow me to test which strategy is the most effective at ensuring that the average daily temperature will remain within acceptable comfort levels. The first task, after surveying the projects, will be to determine what spaces to test. I will choose one private bungalow, and one larger public area (kitchen, conference room, dining hall etc.) in both facilities, that I determine best represent the projects as a whole. The examination will consider seven primary factors: 1. Airflow through the space (temperature, velocity and volume) 2. Indoor Temperature: Stratification from floor to ceiling 3. Outdoor Temperature: Above, below and to the sides of the space (climate conditions) 4. Relative humidity (indoor) 5. C02 levels (indoor) 6. Light (to ensure that an “all vents closed” scenario is not too dark) 7. Noise (to determine whether white noise from the fans and/or whistling vents are a factor) D. Cohen 13 The control scenario for testing at both sites will be with all possible vents and openings used for ventilation closed, and any mechanical equipment (in the case of BRL) off. Using a series of carefully placed data loggers, I will collect dry bulb temperatures outdoors (above, below, and to the sides of the space) as well as indoors (strung from floor to ceiling to determine the temperature stratification), over a twenty-four hour time period. These data loggers will also be used to measure relative humidity and light levels. During this same time period, I will use a Telaire CO2 monitor to measure carbon dioxide levels within the space, information that will allow me to quickly assess if the space is over-or-under-ventilated. At specified intervals I will conduct bubble tests and take anemometer readings to map air circulation pathways and measure temperature, velocity, and volume flow within the space. Also, as needed, I will conduct spot checks to measure indoor noise and illuminance levels. These tests will be repeated with various configurations: partial ventilation scenarios (windows/vents/screens closed with ventilation system on and windows/vents/screens open with ventilation system off) as well as optimal ventilation scenarios (window/vents/screens open and ventilation system on) etc. This data will reveal the successes and failures of each projects ventilation strategy, and allow me to make recommendations regarding possible improvements. While this study is particularly focused on the comparison of two types of natural ventilation strategies, it would be interesting to test a conditioned hotel in Kota Kinabalu (Sabah’s capital) using a similar methodology, to determine a baseline against which these passive systems could be compared. Given time and accessibility restraints, this may or may not be a feasible option. D. Cohen 14 The data will be collected and analyzed in two-week cycles. The first week will be dedicated to collecting the data, while the second will be devoted to extracting, organizing and summarizing the information. Repeating this process will allow me to refine my methodology and account for a variety of weather fluctuations. This process will be documented in blog form so that I can have an ongoing conversation about my methodology and the graphic representation of my findings with my advisor.18 In addition, I will be working on 3D computer models of the projects in both Sketch Up and Revit, which I will use to create graphic explanations of the sustainable strategies (and if time, and my computer allow, conduct an energy analysis using Ecotect to back up my findings and make my analysis more robust). 18 In addition to regular Skype meetings. D. Cohen 15 V. WORK SCHEDULE Week 1-3 (Early June) Get settled in Sabah. Meet with Martin (TREC’s manager/designer) and Ian hall (designer of SUDRS) and tour both sites. Determine study location (public/private space), and begin constructing digital model of TREC facility (existing model of SUDRS facility will be made available to me). Week 4-5 (late June, early July) Research and document (drawings and computer model) sustainable strategies, while refining the hypothesis of the case study. Week 6-7 (mid July) Begin 1st testing/analysis cycle (TREC). Collect data, consolidate data, post to blog and discuss. Post draft graphics for pamphlet to blog (1st round) Week 8-9 (late July, early August) Begin 1st testing/analysis cycle (SUDRS). Collect data, consolidate data, post to blog and discuss. Post draft graphics for pamphlet to blog (2nd round) Week 10-11 (mid August) Second round of testing/analysis (TREC) Wrap up and consolidate documentation of sustainable strategies. Post rough draft of full pamphlet design to blog (focusing on layout) Week 12-13 (late August, early September) Second round of testing/analysis (SUDRS) Post next iteration of pamphlet design Week 14-15 (mid September) Complete Case Study, hand in tentative final draft. Complete pamphlet. Schedule my defense sometime during fall term 2010. Week 16 (late September) Return to Eugene. Revise the final draft. Prepare for my defense. D. Cohen 16 VI. LITERATURE REVIEW - ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY To keep track of all my research and understand where my literature review is lacking I have divided my research into three major sections: Borneo and South East Asia, LEAP and Partners, and Conservation and Eco-Tourism. BORNEO + SOUTH EAST ASIA Culture, history, ecology, and general context There are two books in particular that have been instrumental in helping me begin to understand both the physical and cultural environment I am about to step into: 1) Spalding, Linda. A Dark Place in the Jungle. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill ©1999. ‘A Dark Place In the Jungle’ by Linda Spalding recalls the writer’s two trips to Borneo in the early and late nineties in search of the famous (or as we find out, infamous) Orangutan researcher Birute Galdikas. Spalding begins the book with a quote from E.M. Forster, “We cast a shadow on something wherever we stand and it is no good moving from place to place to save things; because the shadow always follows.” This metaphor seems ever present in her critique of the conservation industry in Borneo and throughout South East Asia. So many people are trying to ‘save’ the rainforest, and yet, as Spalding reveals, the task is not as black and white as some have suggested. Preserving the richness of this place requires revealing the complexity of the rainforest and the layers of subtle stories it contains. This non-fiction text does just that, elegantly capturing the collision of competing interests that are at the heart of Borneo’s conservation effort, as Spalding’s interviews the beloved saviors and the despised traffickers, the indigenous grandmothers and the civic officials. D. Cohen 17 In terms of my work, Spalding offers a unique perspective of the people behind both the problem and the solution in Borneo. Aside from telling a compelling story, Spalding paints a complex portrait of the less documented challenges – corruption, power struggles, cultural customs, and xenophobia – that any conservation effort in Borneo inevitably faces. It is imperative that I understand these issues to the best of my ability if I hope to craft an appropriate design response. 2) Sercombe, Peter and Sellato, Bernard ed. Beyond the Green Myth: Borneo’s Hunter Gatherers in the Twenty-First Century. Copenhagen, Denmark: NIAS Press ©2007. ‘Beyond the Green Myth’ edited by Peter Sercombe and Bernard Sellato is a collection of anthropological analyses of the various nomadic groups indigenous to Borneo (called Punan, Penan and various other names). As the title may suggest, the book takes pains to avoid the tendency to portray Borneo’s aboriginal tribes ‘pictorially,’ as in the cliché of people living in relative harmony with their environment until they are cruelly displaced. Instead it examines the real effects of modernization on the various tribes living throughout the rainforest, in a series of up to date ethnographic studies of the indigenous people of Borneo. The book is a modern vignette of some the last existing hunter-gatherer societies in the world. Tribal culture in Borneo is complex, and developing a full understanding of its intricacies (which of course change from tribe to tribe) is no simple task. I imagine that a large part of my education in this subject will be ‘immersive,’ but this book has given me a solid foundation to start from. D. Cohen 18 LEAP + PARTNERS: Aside from reading through every corner of LEAP’s and it’s partner’s websites, Cynthia Ong (LEAP’s fearless leader) and Ian Hall (her architectural consultant) have been kind enough to send me copies of everything from Grant Proposals and Annual Status Reports to drawings and models of existing and proposed projects. These have been invaluable in helping me orient myself in regards to the plethora of projects and partnerships that are currently evolving in Sabah. Also my ongoing Skype conversations with Cynthia have been very useful to that end. As mentioned in the previous literature analysis, my understanding of LEAP’s inner workings as well as the organization’s relationship with its affiliates will no doubt evolve during my stay. CONSERVATION + ECO-TOURISM: There is a dearth of scholarly articles and reports from a wide variety of Universities, NGO’s and other climate action groups concerning all forms of conservation in Borneo. Thwo of these reports have been particularly useful: 1) Rautner, Mario; Alfred, Raymond J. and Hardiono, Martin. Borneo: Treasure Island at Risk: Status of Forest, Wildlife and related Threats on the Island of Borneo. WWF Germany: Frankfurt am Main © 2005 “From muddy boot plant surveys to high-level policy efforts, WWF has probably deployed the most conceivable approaches to ensure that Borneo’s biodiversity is protected for future generations.” The WWF has worked over the course of the past halfcentury to expand the range and scope of their conservation approaches in Borneo. Recently they facilitated an international agreement between the governments of Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia and Malaysia to conserve an enormous section of Borneo’s D. Cohen 19 interior, a project they call the ‘Heart of Borneo.” This report is an exhaustive study of Borneo’s at risk flora, fauna, and cultural heritage. It continues to be of inestimable value to me because it includes a methodical description of Borneo’s ecology (in terms of regions as well as systems). My interest in creating a ‘patchwork’ of human and animal habitats hinges directly on a thorough understanding of the workings of these systems, which the report provides. 2) Kammen, Daniel M. McNish, Tyler and Gutierrez, Benjamin. Clean Energy Options for Sabah: an analysis of resource availability and cost. (Accessed March 12th 2010) In this recent study conducted for the Sabah Energy Summit, the Berkeley Energy Lab conducted an investigation to identify alternative clean energy options for the state. Its analysis of strategic energy regions (i.e. which energy production method – wind, solar, biomass – would be most effective and where) is helpful, and the report’s conclusion that energy conservation is actually the quickest and cheapest way to meet Borneo’s growing energy demands is of particularly relevance to my work. At this point I have identified three areas or directions in which I plan on expanding my reading. First I want to develop a stronger understanding of the history and current state of eco-tourism and modern architecture in Borneo. Secondly, considering the fact that a large part of this research addresses architects historically romantic attitude towards aboriginal architecture, I would like to deepen my reading on the topic. Lastly, I am continually searching for similar case studies to inform (and professionalize) my methodology. Thank you for reading my prospectus! D. Cohen 20 VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY “ABOUT KOPEL—MESCOT.” MESCOT.org. http://www.mescot.org/KOPEL_MESCOT_About.html (accessed 3 April 2010) Butler, Rhett A. “Borneo.” Mongabay. http://www.mongabay.com/borneo.html. (accessed 10 March 2010) Elzeyadi, Ihab. “A Tale of Two Houses: Environmental Quality, Sustainability, and Indoor Comfort Inside Hassan Fathy's Mit Rehan And A Contemporary Villa in Cairo, Egypt.” Vital Signs Case Study, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1996. http://arch.ced.berkeley.edu/vitalsigns/bld/Casestudies/Abstracts/uwm_twohouse_ab.html “Home Page.” Danum Valley Borneo Rainforest Lodge. http://www.borneorainforestlodge.com/index.htm (accessed 15 April 2010). “Home Page.” LEAP: Land Empowerment Animals People. http://www.leapspiral.org/main.html (accessed 10 January 2010). Kammen, Daniel M. McNish, Tyler and Gutierrez, Benjamin. Clean Energy Options for Sabah: an analysis of resource availability and cost. (work commissioned by Green SURF: Sabah Unite to Re-Power the Future, and completed by the Renewable & Appropriate Energy Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, March 2010) “Projects and Partnerships: MESCOT Initiative, Tungog Rainforest Eco-Camp (TREC).” LEAP: Land Empowerment Animals People. http://www.leapspiral.org/main.html (accessed 28 March 2010). Sercombe, Peter and Sellato, Bernard ed. Beyond the Green Myth: Borneo’s Hunter Gatherers in the Twenty-First Century. Copenhagen, Denmark: NIAS Press ©2007. Spalding, Linda. A Dark Place in the Jungle. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill ©1999. Rautner, Mario; Alfred, Raymond J. and Hardiono, Martin. Borneo: Treasure Island at Risk: Status of Forest, Wildlife and related Threats on the Island of Borneo. WWF Germany: Frankfurt am Main © 2005 “Tungog Rainforest Eco-camp.” MESCOT.org. http://www.mescot.org/TREC-Project_Update.html (accessed 3 April 2010). “Wild Asia’s Annual Responsible Tourism Award.” Wildasia.org. http://www.wildasia.org/main.cfm/RT_Awards/Enter_RT_Awards (accessed 1 April 2010). D. Cohen 21 VIII. GOSSARY OF TOOLS, TERMS, AND ACRONYMS TOOLS19 Air Flow Indicator Bubbles Plastic infused bubbles that last long enough to capture on camera. A simple tool used to determine general airflow patterns. Flicker Checker Simple tool determines fluorescent lamp ballast type. Hobo Temperature/Relative Humidity/Light/External Loggers Data loggers collect indoor and outdoor climate condition readings (temperature/relative humidity/light) over specified time periods. Kestrel 3000 Pocket Weather Meter Measures instantaneous airflow and direction over sites and in buildings as well as temperature and relative humidity. Minolta Illuminance Meter T-10 Offers accurate and easy measurements of illuminance. In photometry, illuminance is the total luminous flux incident on a surface, per unit area. It is a measure of the intensity of the incident light, wavelength-weighted by the luminosity function to correlate with human brightness perception. Pilkington Sun Angle Calculator Provides a relatively simple method of determining solar geometry variables for architectural design. P3 International Kill-A-Watt Figures your electrical expenses by the day, week, month, even an entire year. Can help cut down on costs by finding out if appliances/machines are running efficiently. Can also check the quality of your power by monitoring Voltage, Line Frequency, and Power Factor. Sound Level Meter Measures ambient noise levels. Sylvania Light Meter DS2050 Digital meter that measure illuminance in footcandles. Testo Velocity Stick – 405 V2 Low-cost, mini anemometer measures temperature, velocity, and volume flow. 19 (images and descriptions provided by http://aoc.uoregon.edu/loaner_kits/index.shtml and http://www.professionalequipment.com) D. Cohen 22 Telaire CO2 Meter Measures CO2 (air quality indicator) and temperature. Vaisala Temperature and Humidity Meter A portable hand-held meter that is ideal for spot-checking temperature and humidity levels. Watts Up? PRO ES Electricity Meter Monitors true power in an easy and understandable way. Enables sophisticated data collection and a high level of resolution (over a weeks worth of data can be collected with a resolution between records of only one minute). The sample interval (time between records) is user selectable between one second and one day. TERMS20 Average ambient daily temperature The average ambient daily temperature will be determined by taking the average of the ambient air temperature and the average surface temperatures of the enclosing surfaces of the space. Bubble test See “Air Flow Indicator Bubbles” under tools. Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound composed of two oxygen atoms covalently bonded to a single carbon atom. CO2 is often measured as an air quality indicator. In concentrations of 1% (10,000 ppm), it will make some people feel drowsy. In higher concentrations of 7% to 10% it causes dizziness, headaches, visual and hearing dysfunction, and unconsciousness within a few minutes to an hour. Dry Bulb Temperature The dry-bulb temperature is the temperature of air measured by a thermometer freely exposed to the air but shielded from radiation and moisture. Dry bulb temperature is the temperature that we usually think of as air temperature. It is the temperature measured by a regular thermometer exposed to the airstream. Unlike wet bulb temperature, dry bulb temperature does not indicate the amount of moisture in the air. In construction, it is an important consideration when designing a building for a certain climate. It has been called it one of the most important climate variables for human comfort and building energy efficiency. Illuminance 20 Definitions courtesy of Wikipedia. D. Cohen 23 In photometry, illuminance is the total luminous flux incident on a surface, per unit area. It is a measure of the intensity of the incident light, wavelengthweighted by the luminosity function to correlate with human brightness perception. Relative humidity Relative humidity is a term used to describe the amount of water vapor that exists in a gaseous mixture of air and water vapor. Controlling temperature and relative humidity is important for maintaining human comfort, health and safety, and for the technical requirements of machines and processes buildings and other enclosed spaces. Humans are sensitive to humid air because the human body uses evaporative cooling as the primary mechanism to regulate temperature. Under humid conditions, the rate at which perspiration evaporates on the skin is lower than it would be under arid conditions. Because humans perceive the rate of heat transfer from the body rather than temperature itself, we feel warmer when the relative humidity is high than when it is low. When controlling the climate in buildings using HVAC systems the key is to control the relative humidity in a comfortable range - low enough to be comfortable but high enough to avoid problems associated with very dry air. Thermal Comfort (Comfort Zone/Occupant comfort/Comfort levels) Human thermal comfort is defined by ASHRAE as the state of mind that expresses satisfaction with the surrounding environment (ASHRAE Standard 55). Maintaining thermal comfort for occupants of buildings or other enclosures is one of the important goals of HVAC design engineers. Thermal comfort is affected by heat conduction, convection, radiation, and evaporative heat loss. Thermal comfort is maintained when the heat generated by human metabolism is allowed to dissipate, thus maintaining thermal equilibrium with the surroundings. Any heat gain or loss beyond this generates a sensation of discomfort. It has been long recognized that the sensation of feeling hot or cold is not just dependent on air temperature alone. Stratification Stratification is the formation of air at different densities filling a house or room. It occurs when the ceiling is warmer than the floor. This keeps the hotter, lighter (less dense) air at the ceiling and the colder, heavier (denser) air near the floor. When the ceiling is colder than the floor, stratification does not occur. This situation causes the colder, heavier air to fall along the cold walls and cover the floor. The warmer air, which was over the floor, rises from the center of the house to the ceiling. This convection current keeps the air churning and prevents stratification from occurring. Although stratification is often considered undesirable, this is not necessarily so. In a hot house, it's desirable to keep the hotter air away from the occupants on the floor level. Cathedral ceilings are blamed for stratification, however the real culprit is insufficient insulation that causes wide diurnal temperature swings. D. Cohen 24 ACRONYMS BSBCC: Borneo Sun Bear Conservation Center BRL: Borneo Rainforest Lodge LEAP: Land Empowerment Animals People MESCOT: Model for Environmentally Sustainable Community Tourism SUDRS: Sungai Ulu Danum Research Station TREC: Tungog Rainforest Eco-camp WWF: World Wildlife Foundation