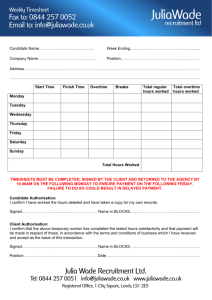

Table 5: Descriptive Analysis of Economic Satisfaction Outcomes by

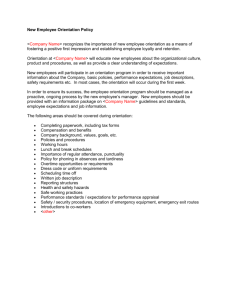

advertisement