(MNCs)' Strategic Location and the Development of Financial

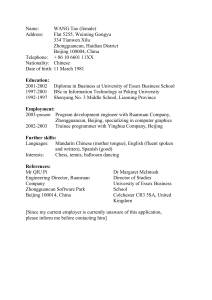

advertisement