the need for a new economic system

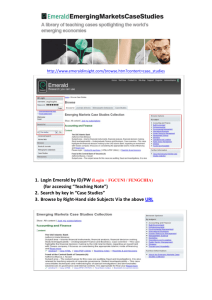

advertisement