Holiday Preference Scale - University of Twente Student Theses

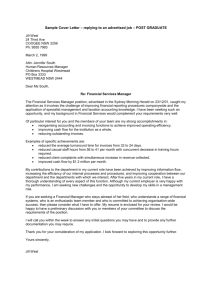

advertisement