Attribution Theory

advertisement

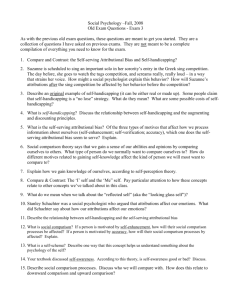

Attribution Theory I. What is an attribution? II. Attributions provide information for our knowledge structures. III. Attribution theory is not a theory. IV. Kelley’s Covariation Model A. Attributions can be made to 1. The Person (The Actor) 2. The Entity a) B. 3. A person-entity combination 4. The circumstances The Covariation Principle: Something is seen as the cause of a behavior if the behavior and the cause appear to covary. 1. C. The ‘target’ of the action. Humans as scientists. Three types of information relevant to covariation 1. Consensus: Does everyone act this way (High), or only the person we are interested in (Low). a) 2. Distinctiveness: Does this person act this way in response to any entity (Low), or only in response to this entity (High). a) 3. Low consensus means the person is involved. High distinctiveness means the entity is involved. Consistency: Does the person usually act this way in response to this entity (High), or is this a unique occurrence (Low). a) If the behavior is not consistent, then it is something unique to these circumstances. D. I. Distinctiveness Consensus Consistency Hi Hi Hi Lo Lo Hi Hi Lo Hi Lo or Hi Lo or Hi Lo Attribution How do we get from acts to dispositions? A. II. What attribution would you make if .... That is, when we see someone do something (acts), how do we know what that tells us about the person (disposition)? Jones’ Correspondent Inference Theory – We make a correspondent inference when we say that a person’s behavior corresponds to something about their dispositions (their attitudes, their personality, etc.) A. If we make a correspondent inference, we can put information into our knowledge structure for that person. III. Two kinds of information. A. Non-common effects (aka Distinctive Effects). 1. B. The more distinctive effects there are, the less likely it is that we can make a “correspondent inference” – that is, the less confident we will be that the act corresponds to some disposition of the actor. Prior Probability 1. The more ‘surprising’ an action is (i.e., the lower the prior probability), the more we can make a correspondent inferences. 2. Originally, Jones talked only about social desirability as the factor affecting prior probability. But, later, he realized that other things could affect it too, including: a) b) Target-based expectancies Category-based expectancies IV. What if we don’t have information about the past? V. A. Facilitating and Inhibiting Causes. B. Discounting: When there are two (or more) facilitating causes, we discount the likelihood that any one of them is the actual cause. C. Augmenting: When there is one facilitating cause, and one or more inhibiting causes, we augment the likelihood that the facilitating cause is the actual cause. Do people really act like scientists? A. How would we know? 1. Rational baseline (normative) models versus descriptive models. VI. A demonstration VII. The Fundamental Attribution Error (Correspondence Bias). A. A failure to adequately take the situation into account. B. The underestimation of consensus. C. Causes of the FAE 1. The role of perceptual salience in the in the F.A.E. 2. The role of culture in the F.A.E. 3. The automatic process of making an internal attribution and the controlled process of adjusting for situational constraints. D. Situational constraints & social roles: The demonstration explained. E. The FAE and the self-fulfilling prophecy. VIII. The actor-observer difference A. The role of perceptual salience B. The role of greater information. We know what we usually do, but not as much about what others usually do.