Week Twelve Materials (Complete)

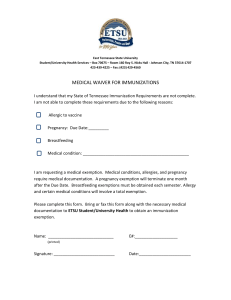

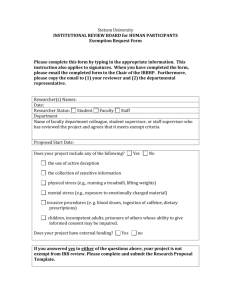

advertisement