Heading - beststudygroupever

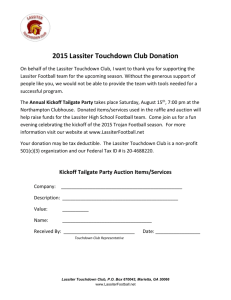

advertisement

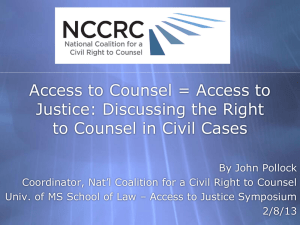

Lassiter v. Department of Social Services Supreme Court of the United States 452 U.S. 18 (1981) Justice Stewart Facts: In the spring of 1975 the District Court of Durham County, NC, adjudicated William Lassiter a neglected child and transferred him out of the custody of his mother Abby Gail Lassiter. In 1976 the defendant was convicted of second degree murder and sentenced to 25-40 years in prison. In 1978 The Department of Social Services petitioned to terminate Ms. Lassiter’s parental rights due to a severance of contact between mother and child. Upon being served with the petition with notice of a hearing, Ms. Lassiter failed to mention the upcoming hearing to the counsel on retainer for her murder conviction. At the hearing the court considered whether Lassiter had had enough time to find legal assistance. Lassiter was deemed to have had enough time; the court did not postpone the hearing, nor did they appoint counsel as Lassiter did not announce she was indigent. Ms. Lassiter held her own counsel and lost her parental rights at the ruling of the court. Procedural Context: Department of Social services filed a petition with the District Court of Durham County, NC to terminate parental rights, and succeeded. Ms. Lassiter failed to reverse the ruling on appeal in the North Carolina Circuit Court of Appeals. The Supreme Court of NC denied her application for discretionary review. US Supreme Court granted certiorari. Issue: Does the termination of parental rights constitute a significant loss of liberty, and as such entitle indigents to a right to counsel via the 6th amendment and applied against the states via the 14th amendment. Holding/Application: The Gagnon precedent holds that there is no constitutionally mandated right to counsel. Because the Eldridge factors were not in favor of Lassiter’s parental interest the court found that there was no deficiency in the fundamental fairness of the hearing by not appointing counsel. Rule: Gagnon v. Scarpelli established that previously sentenced indigent probationers do not have mandated right to counsel; it is a case-by-case decision. Mathews v. Eldridge established a precedent by which three case-by-case elements are evaluated in order to determine the path of due process: the private interests at stake, the government’s interest, and the risk that the procedures used will lead to an erroneous decision. These factors determine whether or not the 6th and 14th amendments come into play. Reasoning: The court held that because the petitioner’s physical liberty was not at stake, the precedents established by Gideon, Argesinger, and In Re Gault did not apply to this case. Evaluating Eldridge means that counsel must be appointed whenever the combination of private interests and the risk of error outweighs the government stake in the proceedings. However, since this evaluation can have many different outcomes, it is impossible to establish a clear and concise guideline. Therefore, according to the precedent established in Gagnon v Scarpelli, the court finds it acceptable that the right to counsel be awarded on a case-by-case decision. Concurring/Dissenting Opinions: Blackmun, dissenting: There are two arguments influencing this dissent. First, the court recognized that a mother has a commanding interest which dwarfs the interest of the state1. Since an indigent will always fail to appropriately represent themselves the risk of error is by default extremely large, and thus the logical conclusion is that the Eldridge factors seem to warrant, prima facie, appointed counsel. The second argument is that Gagnon v Scarpelli was heavily influenced by the informal proceedings of a probationary hearing. In NC, at least, parental termination hearings have the intensity and setup of a criminal proceeding, which invalidates any similarity it has to Gagnon v Scarpelli, and thus the court erred in using Gagnon as a precedent for this case, because the risk of error is overwhelming. Stevens, dissenting: To preface his argument, Stevens decries the court holding that deprivation of an interest in property is less worthy of protection than protection of liberty. The crux of the argument is that the weight of court decisions always supports the idea that the Due Process Clause is designed to combat the deficiency of fundamental fairness in court proceedings wherever they should occur. Therefore, the Eldridge decision should always lead to the right to counsel because any unfairness should be the overriding factor regardless of pecuniary cost or state interest. 1 I disagree; the state had a large interest in insuring the well-being of the child, and it appeared as if Ms. Lassiter was ambivalent at best, toward her child.