Exposition of Meditation I

advertisement

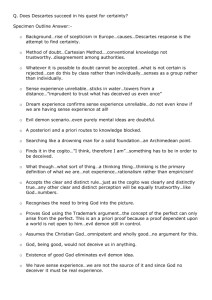

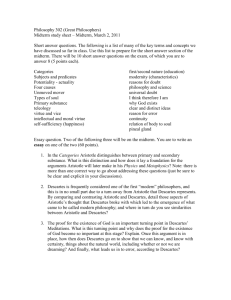

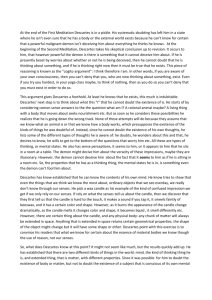

Outline of Meditation I Descartes happily has the time available to carefully examine his beliefs about knowledge and, realizing that some of them have turned out not to be true in the past, put them on a sure foundation. He cuts away a huge number of beliefs by pointing out that they rest on foundational beliefs which, if themselves insecure, will shake the ones above. He proposes to test what he has been regarding as core beliefs. His first target is all the beliefs that rest on experience. We cannot trust our senses since they have proved fallible in the past. It is true that they seem not to be insecure with respect to having hands and feet and so on, but it is possible that we might be dreaming such things – that there are no real hands and feet in the world. But surely dreams must refer to something that is real, something in the physical world? Not necessarily, Descartes replies. Firstly, he points out that the images in dreams may be synthesised from simpler elements. These simpler elements, such as number, place, shape, and duration, could themselves be the merely the (false) inputs from a malign and manipulative spirit (an ‘evil demon’). Outline of Meditation II Descartes continues to search for an Archimedean point of certainty on which he might build. It is clear from Meditation I that such certainty is not available through experience. There is one thing of which he cannot doubt: the evil demon cannot possibly be capable of making him doubt that he doubts: doubting is certain. So, whenever he is doubting (i.e. thinking), he can be certain that he is in existence: cogito ergo sum. So what is his nature? He is not a physical body (which is identical with a corpse); neither is he the animating attributes of the body such as eating and walking (since these require a body which, as shown, is a thing which may be doubted, unlike his thinking). What he is, rather, is a thinking thing: sum res cogitans. The attributes that he has as a thinking thing are the capacities for: doubting, understanding, conceiving, willing, denying, refusing, imagining, and perceiving. The Wax Argument is used to show that knowledge gained through the senses is inferior: the changes that take place in wax as it is heated do not lead us to conclude that the wax has fundamentally changed. No, we understand that the wax stays the same. (Descartes’ point with the wax argument is to say that any body at all has the nature of (just) something that is extended, flexible, and movable.) To understand body (a body, or any body) a human mind is required - animals perceive changes in the wax as well as humans but lack understanding. It is only mind that is capable of grasping innumerable variation - such as in the potential size and form of the wax. Our senses and our imagination are limited to what can be determined, whereas our minds can conceptualise the infinite. From the wax argument he claims that the mind is ‘better known than the body’. By this he means that the mind has no ‘hidden constitution’: once a concept is grasped ‘clearly and distinctly’ it is known with certainty. The case is not the same for physical objects. Outline of Meditation III Descartes says that not only does he know he is a thinking thing, he also knows what is required to give him certainty of truth. He calls this ‘clear and distinct perception’: something he cannot possibly doubt. This knowledge derives from the Cogito. But, he has been mistaken in the past. He turns to mathematical truths: the only way he could think that 2 + 3 = 5 was uncertain was through the possibility of an evil demon. To help to find the distinction between truth and error, he checks his mental furniture and finds three classes of thoughts therein: ideas of objects; feelings about objects; judgements. The first two cannot be wrong (the idea of a goat is the idea of a goat; a desire for wine is a desire for wine) but judgements can be. Judgements most commonly go wrong when judging there to be a reliable link between ideas and an external world. Descartes now turns to where the ideas come from: are they innate; are they adventitious (impressed from outside); are they factitious (synthesised by Descartes himself)? Since his judgement errs with what is apparently adventitious, what are the grounds for believing such ideas to derive from external objects? Two grounds are tested and found wanting: nature teaches us that there is a link (but this has proved faulty when we make mistakes about what we see/hear/etc.) they are not dependent on our will, e.g. we cannot will that a fire gets cooler as we approach it (but they could be - as in dreams). There is no necessary requirement that the idea derives from a physical object. However, there is a third ground on which to skin this cat. We can look at the source of our ideas from the perspective of how much objective reality they contain. [Note that nowadays we would use subjective rather than Descartes’ objective here.] It is clear that the ideas must have come from somewhere – they are the effect of some cause or other. Descartes wonders if he could be the cause of the ideas. This is possible but not for those ideas which have superior qualities to those that he knows he has in mind. Given that you cannot get something superior out of something inferior, how is it that Descartes could produce ideas of, for example, perfection and infinity? He has such ideas in mind, however, and this drives him to the proof of God’s existence. Essentially, the argument goes like this. I have this remarkable concept of an infinitely powerful and infinitely perfect being called God. The content of this concept cannot have been built up out of other mental concepts, nor can it have been derived from my perception of ordinary things, nor from the awareness of my own mind. The source of this remarkable concept must, then, derive from some entity that lies outside my mind and which possesses the features of which the content are representations, i.e. an actually existing infinitely perfect being. Thus, the idea Descartes has of God is innate – a sort of ‘trademark’ left in his mind by his Creator. Outline of Meditation IV Having proved the existence of God, Descartes reminds us that God could not be deceitful (in other words, could not be the evil demon of the First Meditation). He says that this is because there is imperfection in deceit, so it would be a contradiction if God were deceitful. The problem he now turns to is this. If a perfect God created Descartes as a thinking thing, then how is it that Descartes has made mistakes: why hasn’t God made a perfect thinking thing? One reply he considers is that his puny mind could not comprehend what God’s plan is for the Universe as a whole. Perhaps, for the best of reasons, it is necessary for Descartes to make mistakes. Of course, this answer sets a limit on his rationalism so he looks for something better. He examines how it is that errors in his thinking arise. Now his mind’s understanding of something cannot be erroneous. For one thing, his capacity for thinking is a gift from God and so you would expect this to be perfect. Secondly, when he sees something with ‘clear and distinct perception’ he makes no judgements at all and so cannot make an error. But he has another attribute: will. It is this attribute that he uses to make judgements. Like understanding, this is a gift from God and, unlike all his other attributes, he recognises that his will is infinite - he can conceive of no greater amount than that which he possesses already: it is as perfect as it can be. So the will cannot be a source of error either. However, even with these two God-given gifts, Descartes can make mistakes. This is because his will has a wider range than his understanding. When he uses his will to judge things of which he has no understanding, it is no wonder that he falls into error. Notice that if the understanding is clear and distinct, the will is forced to accept it - he cannot judge whether he is a thinking thing, his understanding necessitates he accepts this. This gets God off the hook of the problem of sin (so far as moral evil is concerned, at least). Sin results from Descartes making judgements about matters where he does not have clear and distinct understanding. If he thought more carefully, or refrained from judging where understanding was uncertain, error (and hence sin) could not occur. [Or, of course, he could simply obey God in all things.] Outline of Meditation V Before he can establish the existence of physical objects, Descartes sets out to demonstrate what they consist of in essence. What he finds in his mind are the clear and distinct concepts which apply to the ideas of material objects: number, size, shape, motion, and duration. All these are an aspect of extension and thus it is extension which is the essence of material things [res extensa]. Descartes considers whether certain mental objects he has in his mind are imagined or whether they are prompted by things external to his mind. He uses a triangle as an example to how he cannot have invented these. Though there be no such physical object, nonetheless, he understands there can be an infinite number of triangles but that they will all share certain demonstrable properties such as the three angles adding up to two right angles. He does not invent these properties – they are forced on him through recognition. He is as sure as he can be of the fundamental truths of arithmetic and geometry. This idea of the properties of a triangle being deducible, with certainty, from the concept of a triangle leads Descartes to his second proof of God’s existence. It is a version of the Ontological Argument and runs like this. 1. 2. 3. 4. I have the concept of a unique and wholly perfect being (God) in my mind. Existence is more perfect than non-existence. Hence, a perfect being includes existence as one of its attributes. Therefore, God exists. What is special about God is that his existence is necessary (unlike, say a winged horse which Descartes can also have as a concept). It is necessary because to say ‘God does not exist’ leads to a contradiction: ‘The perfect being which exists does not exist’. He notes that God guarantees knowledge (i.e. that which he apprehends clearly and distinctly) is true. Without God, nothing can be said to be true. Outline of Meditation VI Here, Descartes sets out to establish that physical things, res extensa, do exist; and demonstrate the real distinction between mind and body. He starts by distinguishing between his imagination (which he takes to be an attribute of the body) and pure understanding (an attribute of the mind). To do this he uses the example of a geometrical figure, a chiliagon. The imagination, he says, cannot produce such a thousand-sided figure. And yet pure understanding can grasp it and deduce from it certain properties which it must possess. This shows that imagination is not a part of the mind: for one thing, it takes much more effort to imagine something like a perfect pentagon than it does to understand, say, that it can be formed from five congruent equilateral triangles. He also notes that imagination is not a necessary part of his nature (which, remember, is a thinking thing) since he could have no imagination at all and yet would still exist. But if the imagination is not a part of the mind then it must be part of something else and the most obvious candidate is the body. However, he is, as yet, uncertain that the body (and other physical objects) exist. What he takes to be his sensations of objects from a world external to his mind have, it’s true, been erroneous in the past. What he can say about these sensations is that there seems to be a natural link between them and his sensations: when he approaches the fire, he feels warmer, for example. His reason for doubting that there was this natural link was the possibility of an evil demon. Given the existence of God, this is no longer tenable. So, how is he now sure that there are physical objects? Firstly, he reminds us that he knows that he exists solely as a thinking thing. Secondly, he has the clear and distinct concept of body whose essence (as in Meditation V) is extension. Since Descartes can imagine (extended) physical objects, and since imagination is not an attribute of mind, then the ideas of physical objects he has must be derived from outside his mind. Thus, either physical objects exist or God is feeding him ideas of physical objects. Because God is good, he wouldn’t deceive Descartes in this way and so he can be sure of the physical world. Mind and body are two substances because they have different properties: the mind is a non-extended thinking thing; the body is an extended, non-thinking thing. Further, since mind and body can exist apart (in that it is logically possible for this to happen as shown by the Cogito) then mind does not depend on the body for existence. Later, Descartes asserts that the body is divisible whereas the mind is indivisible. (This is another attribute which shows that they are distinct.) In the rest of the Meditation, he treats the common-sense link between human mind and human body. The usual reading of this is that, while acknowledging that humans consist of two substances, he offers no inkling of how these could possibly interact. A more sympathetic reading (due to Cottingham) is that Descartes saw human beings as a third sort of thing: a resultant of the admixture of mind and body which is not reducible to either component.