III - Justin Hughes

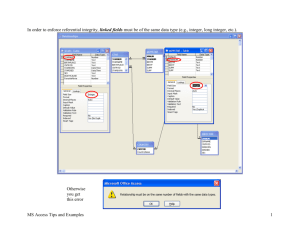

advertisement