further details (Office document, 59kB)

advertisement

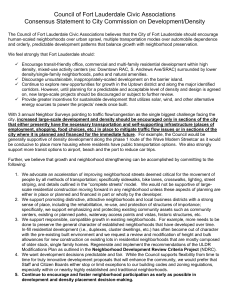

"SOCIAL MIX" AND NEIGHBOURHOOD REVITALIZATION: LINKING GLOBALIZED POLICY PERSPECTIVES TO LOCALLY EMBEDDED EXPERIENCES - TOWARD A TRANSATLANTIC COMPARISON Context and objectives of International Collaboration: “The paradox is that while the policy formulation process may be globalizing, implementation and outcomes remain stubbornly ‘embedded’ at the local level.” (Peck 1999 : 133) A reoccurring problem of urban social policy and urban planning is ‘social mix’ or how and at what spatial scale of residence can groups of different socio-economic status co-exist comfortably, in the face of housing market dynamics and residential choices of wealthy groups that tend to reinforce social differentiation of residential space. Ultimately, the underlying ideal is that the social composition of the resident population of a particular municipality, district or neighborhood, should reflect the diversity of society in general. Initially based in conceptions of utopia, the desire to create social mix lead to the creation of English new towns (Sarkissian 1976), and resurged in the last decades with large public housing projects in France (Chamboredon et Lemaire 1970; Pinçon 1981), housing cooperatives or the conversion of obsolete industrial zones into housing in Canadian cities (Dansereau et al. 1997; Hulchanski 1984; Rodman et Cooper 1995), and new residential neighborhoods in American suburbs (Calavita et al. 1997). At the turn of the 21st century, social mix is making a resurgence at the international scale as a fundamental element of urban policies (Dansereau 2003). Social mix represents one of the key issues at play in the fight against segregation and urban fragmentation (Musterd and Andersson 2005; see Anderson and van Kempen 2001), as well as a form of promoting the social sustainability of cities (Kearns and Turok 2003; Stren and Polèse 2000). Discussion of this issue evokes on the one hand, the impoverishment of certain neighborhoods and the formation of entrenched populations at long term risk of social exclusion (Paugam 1996), while on the other hand the increasing popularity of gated communities and the resistance of upper income groups to build affordable housing in their territories (Atkinson 2005; Burchell et al. 2000; Preteceille 2003). The difficulty in assuring a sufficient number of affordable housing units to modest income households in central areas of cities with advanced tertiary sectors, (ex. London, Mayor’s Housing Commission 2000) which are subjected to more and more intensive gentrification, attributable to the professionalization of the workforce (Hamnett 2000a,b; Rhein 1998; Rose 1989) is also frequently discussed. Underlying the proliferation of debates surrounding social mix at the scale of the neighborhood, district or municipality is a larger preoccupation with social inclusion in both material and symbolic plans (European Foundation 2004). Although there appears to be consensus surrounding the principles of social mix, nuances of vocabulary such as ‘diversity’ or ‘balancing’ testify to divergence in both goals and aims and the manner of attaining them (Béhar et al. 2004; Cameron 2003; Smith 2003; Tissot 2005; Wood 2003). Among the reasons cited to promote (or to conserve) social mix (see Bacqué 2003; Dansereau et al. 2003; Lelévrier 2005; Rose 2004), one might mention the will to eliminate large spatial concentrations of poverty which are more susceptible to social exclusion; to encourage contact between middleclass and marginalized populations to accrue increased chances of social mobility for modest income earners; to increase equity in access to urban services through increased support for modest income earners in neighborhoods which are more well-off or are under-going gentrification; to diversify the residential market in low-income neighborhoods in order to accommodate genuine home businesses. It is also a question of promoting social cohesion while postulating that social mixing in spaces of everyday life helps facilitate understanding of the other. Lastly, social mix is associated with functional mix (Grant 2002), new urbanism (Larsen 2005) and with urban livability, which reflects issues surrounding the economic competitiveness of cities rather than that of social exclusion (Lees 2003). However, some of these policy objectives are based on premises strongly criticized in the literature (e.g. Ostendorf and Al 2001). Others are highly dependent on the specific national and local contexts in which they were initially elaborated. And yet, public action seems to converge from one country to another; the increasing frequency of policy transfers is not always tempered in terms of local references and contexts (Murie 2001; Peck and Tickell 2002). Thus, in the past three or four years, there has been an intensification of the international debate surrounding social mix in order to better understand and clarify public action in this domain. Extremely interesting networks are developing, on the one hand between British and American researchers (Rowntree Foundation/Brookings Institution: Berube 2005), in addition to within the EU (for example, the French Minister of Equipment, Transport and Housing as part of the Master Plan of Construction and Architecture of is currently financing a pilot project ‘Social Mix: A Shared European Preoccupation?’. Further, social experiments around programs such as Moving to Opportunity in the United States have created contexts for cross evaluations conducted by several research teams. However, until now Canadian researchers are not present in this networking dynamic in large part because donor agencies tend to take large regional economic blocks (European Union, NAFTA) as reference territories. Thus, it is noted that in the diverse comparative analyses outlined on the debates and policies of social mix schemes of recent years, as well as in bibliographies based on convincing data (Arthurson 2004; Atkinson 2005; Donzelot et al. 2003; Kleinhans 2004; Talen 2006) that while these works have covered many different countries, they have rarely made stopovers in Canada. Further, these works are for the most part shrouded in linguistic barriers. Canadian research however, has already made an interesting contribution to both theoretical and practical knowledge surrounding social mix and as such we believe it is currently in a good position to have an impact on international research. Its particular strengths include : 1) understanding of the neccessary conditions for successful ‘programmed’ social mix projects in urban centers and the experiences of local residents in these projects (Dansereau et al. 1997; Rodman et Cooper 1995; Séguin 1997; Vischer 1984); 2) documentation of the various destinies of gentrifying neighborhoods (gentrification or maintainence of social mix in the long term) (Caulfield, 1994; Ley 1996; Rose 1996). Moreover, in Quebec, a third strong line of inquiry has developed as the result of the cross-fertilization of French and English intellectual traditions in urban studies. Thus, research has grasped modes of cohabitation present in Montreal neighbourhoods which combine socio-economic diversity and ethnic diversity at the neighborhood or the micro-local scale, which can have an impact on the forms of public sociobility (Germain et al. 1995) and can influence the sustainable or transitional character of social mix. On the one hand, concepts developed by European researchers (Grafmeyer 1999; Remy and Voye 1992) were useful to grasp the way in which dynamics of cohabitation are shaped by the inconsequential character of interactions which take place in the public spaces of the neighborhood. On the other hand, the concept of weak ties (Henning and Lieberg 1996) drawn from the Anglo-American approach to the sociology of networks (Bridge 2002; Granovetter 1973) has been put to good use in studies examining relationships between neighbors in situations where the is a high degree of mix (Carrasco et al. 1999; Fortin 2002; Ray 2002; Rose et al. In press). It is highly possible that to date the impact of Canadian contributions has been hampered by what Lawrence Berg (2004) calls the process of ‘scaling knowledge’ by which Canadian research, and a fortiori Quebecoise, can be percieved as more localised and deeply rooted and less susceptible to generating theories or results that can be transferred to other contexts, than British, American or even French research (Rose and Gilbert 2005). We would like to act to change this situation by proposing a project of international collaboration on both social mix policies and experiences which reunites a team of researchers : two French (Housing Research Center UMR LOUEST, CNRS), two British (Centre for Urban Studies, University of Bristol) and two Canadians (Urbanization, Culture and Society, INRS). Our goal is to exceed the stage of the comparisons ex post facto and to create a mode of collaboration making it possible to cross both national and linguistic barriers (Whitehand 2005). This will involve in part implementing the same line of questioning and elaborating a generalizable research protocol, and futher, testing this protocol through a pilot project in three different geographic areas, in Canada, France and England, in central districts of three cities known to be making a strong turn towards the advanced tertiary sector : Montreal, Paris and Bristol. In fact, despite the internationalization of the debate surrounding social mix, no integrated protocol has been created to analyze structural variations in the precise objectives to be aimed at in public policies, in the means of implementation and in the experiences of cohabitation of the original and new residents in the neighborhoods concerned. These variations are two-fold and are situated at the extremes of scale in public action : on the one hand, that of the plan of national/provincial Welfare states and housing programs (as well as modes of immigration and citizenship); and the other hand, that of the micro-local context. In fact, the existing European and transatlantic networks have only explored the national scale, whereas, according to us, the municipal scale plays a crucial mediating role (Bacque and Fol 2005) which is poorly integrated in the conceptual frameworks (see Gough 2002; Sellers 2005) and even less documented by empirical studies. In other words, it is a question of eloborating a multi-scaled perspective which combines not only different levels of government but also integrates the contours and particular trajectories of each district. Methodological Strategy Our project divides in three principle steps. STEP 1: Common questioning of the concept and policies of social mix It is a question of assembling a grid of questioning to compare the way in which the notion of social mix is mobilized in three different urban policy contexts. At this stage of the project, we indicate the larger themes which structure the questioning (nonexhaustive and formulated in a provisionary fashion): Formation of the set of themes surrounding social mix. In which regional and local contexts do these themes re-appear in recent years? Links with interventations aimed at disadvantaged neighborhoods? From which level(s) of the state do these policies emanate (governance context, degree of municipal autonomy…)? Global objectives touched on : territorial equity, social integration (individuals), social inclusion (groups), social cohesion, sustainability? Indicators/measurements used to justify interventions? Vocabulary and associated connotations : mix, diversity, housing tenure mix (Turstall 2003), (re)-balancing…? Meaning of adjective in the term « social mix » : socio-economic mix, demographic (generations, types of households/families, ethnic, ‘racial’…? Places concerned : new private residential developments (fair share policies), public housing estates, old districts with mixed residential fabric…? Operations aiming at the insertion of low or modest-income households in middle-class neighborhoods, or the inverse? Relationship between interventions by means of housing provision and measures targeting underpriviledged individuals? Aimed at commericial streets, other public spaces, utility services? Links evoked between residential mix and education? Operational mechanisms : inclusionary and incentive zoning, diversitification of legal statutes of occupation (tenure), allotment of social housing…? Types of actors, partnerships…? Spatial scale of ‘programmed’ social mix : district, neighborhood, street block, building….? We will supplement this grid for the countries chosen by secondary sources. At the municipal level, we will not neccesarily limit ourselves to our three respective cities, if we do not find case studies exemplifying all types of social mix present in the three countries. This exercise will permit us to better understand the sources of structuring variations; for example (non-exhaustive) : Historical forms and current trajectories of the welfare state and the role of the local scale as a place of renegotiation; How the type of regime (Esping-Anderson 1990) is translated into housing systems (Presence of redistibutive mechanisms mitigating the effects of territorial inscription of social inequalities? Can one interpret certain interventions in favour of social mix in terms of a « re-socialization » by local authorities vis a vis concrete expressions of the limits and contradictions of neoliberalism (Gough 2002)? Systems of immigration and citizenship as well as socio-economique trajectories of racialized minorities; this is a fundamental benchmark of the debate surrounding social mix in France, and is growing in extent in some urban contexts of England and Canada. STEP 2 : COMMON QUESTIONING ON THE MODES OF INTERACTION AND COHABITATION IN MIXED NEIGHBORHOODS/VICINITIES In this stage our grid of questioning will aim at clarifying different theoretical corpus allowing us to approach notions of copresence and the interaction between different groups in mixed neighborhoods, and the significance of these interactions The types of copresence or social interaction evoked in the literature of the two Atlantic coasts and the English Channel, in policy orientation documents, how they are conceptualized and which values and norms are associated with them : neighbouring (Forrest and Bridge 2006) or modes of neighborliness, coexistance, avoidance, social tectonics (Bultler and Robson 2003) cohabitation, mixing, share, respect for differences, affiliation to common standards, respectability, ordinariness (Allen et al. 2005), neighborliness (Crow et al 2002), community-building in which directions, with which aims (Bacque et al. 2005; Body-Gendrot 2005; Kadushin et al. 2005; Miller 1992)? Comparison of similarities and differences between the francophone and anglophone literature, explanatory assumptions of which variations in the capacity of mixed neighborhood spaces favor the taming of differences or rather avoidance and withdrawl (Amin 2002; Bourdin 2004; Germain 1999; Grafmeyer 1995; Rose et al in press); what factors make these interactions at the micro-scale end up « erasing or accentuating sterotypes » (Andrew 2002 : 10). This exercise will be crucial in order to work out generalizable research instruments across our three countries and in our three districts, to trace the modes of interaction, the expectations and the lived experiences of the actors and residents of mixed neighborhoods and districts. For example, the classic indicators of British and American sociology on the quality of neighborhood relationships and on the feeling of local membership are not neccesarily transferrable to the French context. STEP 3 : ELABORATION OF GENERALIZABLE INVESTIGATIVE INSTRUMENTS AND TEST BY MEANS OF A PILOT INQUIRY ON THREE GROUNDS We propose to test this comparative analysis protocol by means of a pilot study lead in three cities known having strong economic restructuring towards the avanced tertiary economy during the last two decades (although Paris, Montreal and Bristol occupy very different positions within world and national urban hierarchies). The central districts we will target – in Montreal : Hochelaga-Maisionneuve; in Paris : La Goutte d’Or; in Bristol : Easton – are all considered (either the whole district or certain sectors) as very disadvantaged. Nevertheless, they possess a strong associative fabric and have traditions of communtiy organization. Above all, they respresent case studies which have been neglected in the literature although frequent in old urban districts, that of a « mixed » residential tissue at a small scale due to the insertion of social housing in the midst of private residences. They all are targeted by policies of territorialized interventions. The programs rising from these policies aim at an improvement of the local habitat, the maintenance of original residents who are already upwardly mobile, the arrival of new middle-class residents, as well as the upward mobility of the residents with precarious status. With this intention, they develop a series of actions to widen the residential market or to support the local economic development to which are added other measures directed at the most underprivileged social groups. At the same time, certain sections of these three neighborhoods are beginning to be invested in by more affluent populations who are attracted by the financial accessibility of housing, in the context of regional real estate markets which have seen a rapid increase in property prices since the mid-1990’s. The net result of these territorialized policies and the “spontaneous” residential movements is that in each case socio-economic mix is reinforced by “endogenous” and “exogenous” dynamics (Dansereau et al 2003). The following field methods will be used by deploying designed instruments, in the light of the results of stages 1 and 2, to generate generalizable data: analysis of documentary sources, such as the local press, to discover the representations of the district which are presented there and to grasp the local context in which the debate on social mix is situated; we could also observe public meetings (district councils, briefings) in order to identify who speaks around which issues. interviews with key informants, relating to places where they mix with or avoid populations direct observation to identify the locations of various types of cohabitation and of public sociability in a diversity of places; for example, neighborhood parks are an object of diverse practices which may go alongside or confront and the evolution of commercial streets is one of the strong elements of gentrification (Lehman-Frisch 2002; Simon 1997). This method supplements that of interviews because it escapes the filtering practices of speech. semi-structured discussions with some old and new residents to know their points of view on social mix and to see whether a common image of the district emerges (Butler and Robson 2003; Germain 1998; Pink 2004). We will also tackle their trajectories and residential intentions, in order to grasp the range of reasons for which people find themselves gathered in the same neighborhood (Lefeuvre 2005). We will also ask them to address their neighborhood practices and their use of public space and local resources, which will permit us to see to what degree the desire to live in the area corresponds to a feeling of or desire for membership (Bridge and Watson 2002). Additional Outcomes: The subsidy will enable us to reinforce already existing intellectual bonds within our team, through the collective design of methodological instruments, the collective organization of scientific discussion and through the co-writing of communications, scientific articles, and other requests for funding. Lastly, by associating municipal authorities in the empirical part of our research, we hope to advance the debate on which key characteristics make policies comparable and thus transferable from one context to an other, in short to support a critical but constructive interrogation on the concept of “best practices” (Oxley 2001).