Liszt B min Sonata

advertisement

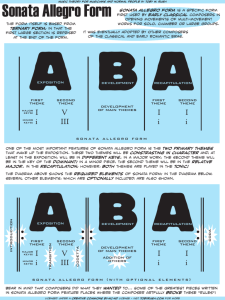

M434 Piano Literature- final paper 1st draft Liszt’s B min Sonata Jeung-Yoon Lee 1.1 Introduction Among the crowning achievements of Weimer years( ) was the composition of the Piano Sonata B minor. Composed 1851-1853, it represents one of the most original contributions to sonata form in nineteenth century. The sonata was published in 1854 with a dedication to Robert Schumann (a reciprocal gesture for the dedication of Schumann’s C major Fantasy to Liszt, some years earlier). From now we will examine this piece by following order. -What is sonata form? -Influences on the Liszt’s B minor sonata -Understanding B minor sonata -(Reception) -Conclusion 2.1 Traditional Sonata form Sonata form- Antonin Reicha and Carl Czerny, along with Adolf Marx, they were the most influential codifiers of sonata form in the nineteenth century, and it is from their work that we drive the outline of the form now commonly taught in schools and universities. As can be seen from the titles of the treatises- Reicha’s Traite de haute composition musical (1826), Marx’s Die Lehre von der musikalischen Komposition (1845) and Czerny’s school of Practial Composition (1848) – their purpose was to provide a guide for composers in the writing of sonata form movements, rather than in the analysis pf past Classical practice. According to Czerny and Reicha, sonata form, defined as the form of the first movement of a sonata or symphony, consisted of three parts: exposition, development and recapitulation. … 2.2 Influences on B min Sonata Most of Liszt’s creative efforts in Weimar were concentrated on following Beethoven’s example, especially in the rejuvenation of sonata form. Although he did not specifically tell which works of Beethoven, one of the most influential on his general approach to sonata form was the finale of the Ninth Symphony. In this variation movement we find the germ of so many Lisztian traits. The variations are organized as a large-scale sonata structure in D major, with the second subject, a transformation of the main theme into Turkish march in Bb (the flattened submediant); then comes a fugal development followed by a recapitulation. The recapitulation is interrupted by a slow section, based on a new theme begging with subdominant. IN fact, this slow section is analogues to secondary development sometimes found in recapitulations. Its theme is immediately taken up again, in the tonic, as a glorious counterpoint to the principal ‘Ode to Joy’ melody for the second, and by far the larger, section of the recapitulation. If we consider the march as a scherzo substitute, we have all the ingredients of a four-movement work bound to one, and underpinned by thematic transformation. Although there are important differences in detail, this is the essence that often describes the Liszt’s sonata. The idea of binding several movements into one might be considered fundamentally Beethovenian, but already by 1822 Schubert in his Wanderer Fantasy had successfully achieved the same thing. The Wanderer Fantasy was one of Liszt’s favorite concert pieces, which he made arrangement for piano and orchestra in 1851. Many fantasies at that time were quite short and had contrasting sections in various keys and tempos. However, Schubert made more complex plan, using thematic transformation to connect sections together in a scheme of first section(C major), slow section(C# min-E maj), scherzo (Ab major) and finale (C maj, beginning with fugal exposition). Maybe is not fair to give all the credit to Liszt for inventing thematic transformation. By the age of thirteen Liszt learned that it was possible to accommodate sections of varied characters within basic sonata structures. His ‘Impromptu on themes of Rossini and Spotini’ of 1824 is composed this way. Even though its weak quality, it shows that Liszt already started that kind of experiment in his early age. He also observed that the concerto form was treated in many free ways by Schumann, Weber, Mendelssohn, John Field and Herz. (There were similar attempt to make this concerto in one movement among them.) Although there were precedents for concerti and fantasies in one continuous movement, there was none for the piano sonata yet. Liszt’s approach in the B min sonata can be describing d as a combination of fantasy, which was normally in one movement, with the traditional sonata. Beethoven also had this kind of composition such as ‘quisi una fantasia’ op.27. These sonatas are directed to be played without break between movements. For last, Liszt adopted Chopin and Hummel’s way. For his third sonata, op.58, Chopin adopted a scheme unused by Hummel in his sonata in F# minor, op.81, namely a highly chromatic transition hinting various remote keys before long period in the dominant of the relative major establishes it as real second key. This kind of procedure made new exotic sound. Liszt, who admired Chopin and Hummel’s sonatas, used similar way in his B min sonata. (The double function structure was to have no successor until Schoenberg did something similar in his first chamber symphony more than fifty years later.) 2.3 Understanding the Sonata There are three major opinions about analyzing the Sonata: The analysis of W.S. Newman has been most influential, particularly in his coining of the apt term ‘double function’ form, a structure that can be considered both as on continuous movement and simultaneously as a composite of the of a multi-movement work. More concretely speaking, the Sonata exhibits elements of a first movement-slow second movement-scherzo-finale though in one movement. Newman was the first one who brought up this double function idea, although Dohnanyi apparently taught something similar in the Budapest Liszt Academy in early nineteenth century. Whatever the difference are, Newman, Longyear and Winklhofer are at least agreed on that the Sonata is not a programmic work, and that as a result analysis of it can only proceed on only musical terms. Liszt himself never gave the slightest hint that the Sonata had a programme, but this is no problem, as several writers have been kind enough to supply one for him.(necessary?) 2.3.1 Programmatic interpretations These programmatic approaches range from vague to the very (?) specific. The vaguest one is that of Peter Raabe, who thought that the Sonata was a musical autobiography, exploring the contradictory elements within Liszt himself, his triumphs and disappointments, his loves and hates.Raabe’s theory was nevertheless given sterling support by the Hollywood film of Liszt’s life, Song without end. The second category of programmatic interpretation is the eschatological.(?) Tibor Szasz (‘) has advanced the revelation that the Sonata is about struggling between God and Lucifer for the soul of man, based on the Bible and Milton’s Paradise Lost. (add more detail?) The Faust interpretation has been the most enduring of all programmatic descriptions. Cortot, in his Salabert edition of the Sonata, gives it as a fact. Even the preface to the New Liszt Edition takes this as read. However, the only reason they believe this is because of the thematic similarities with he Faust symphony. But then, it is also almost identical with one of the Grand Concert-solo themes, for which no one has ever suggested a programme music, and also to a theme in the symphonic poem Ce qu’on entend sur la montaqne. It is, in fact, one of the Liszt’s favorite melody.(add?) Moreover, the theme 3 of the sonata has strong resemblance to the theme in the second movement of Alkan’s Grande sonate of 1848, the movement named Quasi Faust. (check the flowing) (ex) Lina Ramann, however, who wrote the first major biography of Liszt, and who questioned the composer closely on the origins of his works, stated (other word?) categorically that the Sonata was not inspired by a programme even though Liszt himself was quite capable of creating programme for his music. Ironically, the one dramatic association made by composer himself was that the Sonata theme 2 with the defiant (?) mood of Beethoven’s Coriolian Overture. Liszt told this to his pupil August Stradal during a lesson on the Sonata in order to help Stradal to capture the correct mood for performance on this theme. 2.3.2 Musical analysis Both Newman and Longyear agreed that the Sonata can be considered either as a single movement sonata form or as a multi-movements, with a slow movements and scherzo (meaning fugue section here). They differ over whether the sections are divided four movements (Newman) or three (Lonyear). On the other hand, Winklhofer sees the Sonata only as one single movement. She admits that there is a slow movement in the middle of the Sonata, but refuses to identify the fugue with a scherzo. Winkklhofer thought the slow movement as a ‘slow sub movement’ in sonata form. In Longyear’s case, he also denies the ‘scherzando’ fugue an independent movement. He includes it in his finale movement. The fascination of the work is increased by leaving the answer open: the fugue is a ‘scherzo’if the performer chooses to project it as such, and the listener decides to hear it as so. The differences between Winklhofer and Newman are more acute. Longyear’s threemovement division of the Sonata is consistent with his one movement analysis. In other words, his ‘first movement’ is only a notional term that comprises the exposition and development of the Sonata as a whole, without the closing recapitulation that we would find in a true first movement. Newman’s ‘first movement’ is the same part of the Sonata as Longyear’s(measure 1-330), but here described as a self-contained unit in ‘incomplete sonatina from’, by which he means ‘sonata form in which a simple recapitulation replaces the development section.’(what so called slow movement sonata form) What Lonyear and Winklhofer consider as the beginning of the development, Newman hears as a recapitulation with its own mini coda. In his view of the Sonata as a single movement, the development begins with the Andante sostenuto. Personally, I cannot agree to Newman’s idea at this point.. Bearing in mind of all these confusing pictures, let us look at the Sonata in more detail, first as an single movement sonata, which all those three scholars agree. Giving his work the simple title ‘Sonata’, Liszt ensured that the pice would be initially considered in relation to the familiar sonata type. The overall key scheme conforms strictly to this sonata key scheme., unlike most of Liszt’s sonata form symphonic poems. The use of the relative major for the second subject, and the dominant major key for the central Andante sostenuto were quite conservative which focused on the more radical elements of the Sonata. One thing important here is that even though Liszt’s tonal goal s may be conventional, his means of reaching them are dramatically progressive and new. Thematically, the entire melodic texture of this piece is constructed out of only five themes. The first three scarcely more that fragments in themselves, but capable of forming longer units by transformation or synthesis.(ex) Ex.p.35 Theme 1 (Lento assai, measure 1-7) grows out of the slow syncopated repetition of the note G (muffled timpani strokes, according to the Liszt Padagogium, and not pizzicato string as commonly played), the third repetition initiating a descending scale, firstly GPhrygian mode, secondly Hungarian gypsy scale. These two different scales create a pensive, brooding impression, enhancing the tentative grouping of the repeated Gs. The extra harmonic flavor given by the tritone G-C# of the gypsy scale, further emphasized by sustaining G octave in the right hand, increases the feeling of expectancy, fulfilled when a third repeat of the syncopated Gs leads not to another scalar figure, but instead to theme 2(Allegro energico, m 8-13), a motif outlining diminished seventh chord, the accented notes D (m10) and A (m12) making harsh seventh suspensions against the diminished harmony. (This technique of a single line creating its own harmonic tension and resolution can be trace to Bach’s unaccompanied instrumental music.) Theme 2 reminded Liszt of the Coriolan of Beethoven’s overture and Collin’s play, haughtily announcing ‘Why sound I show my sorrow to them? I bear them within me, and proudly hide them away.’ Theme 3 (m 13-17) was also specifically characterized by Liszt as a ‘Hammerschlag’(hammer-blow), striking and pounding single note repetitions. Repetitions are an important feature of all three themes. Theme 2 takes off from the repeated G of theme 1, and transformed to octaves (m8), and theme 3 starts by repeating A# which ended theme 2, using it as part of the upbeat to its repeated note phrases. Thus each new theme begins by pivoting on the note that finished the previous one. This gives sense of continuous flowing between themes. The tonality of these themes 1,2,3 is ambiguous though. The harmony of theme 1 suggests c minor, the Gs function as a dominant. Theme 2 is just diminished chord (A#C#-E-G), which can be resolved to b minor. Yet, theme 3 continues diminished seventh harmony. In terms of phrase structure, the typical Romantic four bar structure is abandoned. Theme 1 is two three bar phrases, a potential third phrase cut short by theme 2, a five bar unit. Theme 3 is more regular, as befits hammer blows, making two bar structure. When we consider all these complexity of this opening page- the fragmentary nature of the themes, the tonal obscurity, the irregular phrasing- it is understandable why this piece struck some nineteenth century audiences as completely incomprehensible. Theme 4 appears at measure ( ), second subject. Theme 4, 5 are at m ( ) in the slow movement. Theme 5 can be seen as thematic transformation (augmentation) of theme 3. The Andante sostenuto (compound ternary form?) is similar to late Beethoven’s works. The F# major, which is dominant of tonic B minor, is also Liszt’s ‘beatific’ key. The three-part fugue, which reminds us Beethoven, is both third movement and an extended return to the recapitulation, in B minor (m 533.check!). (Help needed. I’m not sure how much detail I should cover here.) 2.4 Reception The first performance of this piece was given by Hans von Bulow(Liszt’s student) in Berlin on 22 January 1857. The work’s reception was not promising. Otto Gumprecht described it as ‘ and invitation to hissing and stamping’, while Gustav Engel said that it conflicted both with nature and with logic. The fame of the B minor sonata recovered slowly before the turn of the century. One of the best known was the private performance that Karl Klindworth gave to Richard Wagner in London, on 5 April 1855. 3. Conclusion