Newsletter

advertisement

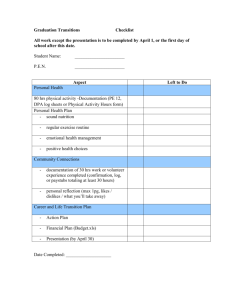

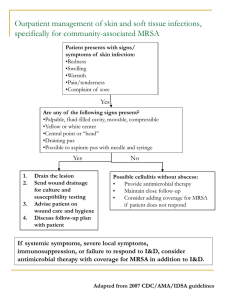

The Family Practice Newsletter Benzodiazepines and Anxiety April 2013 Inside this Issue Benzodiazepines and Anxiety Community Acquired MRSA Cellulitis (CAMRSA) Osteoarthritis **Updated** Comprehensive $4 List Available www.doctorsfp.com Newsletter Contact Information: Megan Keller, PharmD MKELLER4@OhioHealth.com Doctors Hospital Family Practice 2030 Stringtown Road, Suite 300 Grove City, Ohio 43123 1 Jessica Davis, PharmD Candidate When treating a patient’s anxiety with either short- or long-term therapy, there are four major drug classes to choose from: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines (BZDs). Other therapies involve controlling the symptoms associated with anxiety disorders (such as beta blocker). BZDs are theorized to work through the inhibitory neurotransmitter γaminobutyric acid (GABA) and act at the limbic, thalamic, and hypothalamic levels of the CNS, producing anxiolytic, sedative, hypnotic, skeletal muscle relaxant, and anticonvulsant effects. They can be used to treat every type of anxiety disorder and are the most commonly prescribed class of agents for treatment of anxiety. BZDs are considered to be more effective than barbiturates, meprobamate, or buspirone for the treatment of anxiety symptoms and disorder. BZDs should be prescribed for shortterm use (4-10 wks) in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or for shortterm alleviation of anxiety symptoms. Long-term use (> 4 months) for GAD has not yet been studied. They have, however, been studied at periods greater than 8 months and determined to not be successful in treating panic disorders. Specifically, alprazolam and clonazepam are used for the short-term treatment of panic disorder without agoraphobia. patient, lorazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam (think “LOT”) are the safest choices since they’re metabolized through conjugation. Metabolism of some BZDs (e.g., alprazolam, clorazepate, diazepam, flurazepam, and midazolam) is achieved through oxidation by the cytochrome P-450 CYP3A. Use of these BZDs with agents that inhibit (e.g., some azole antifungals, some macrolide antibiotics, HIV protease inhibitors, some calciumchannel blocking agents, some SSRIs, nefazodone, grapefruit juice) this enzyme will increase the plasma concentrations of these drugs. Conversely, agents that induce (e.g., carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, rifampin) this enzyme will decrease the plasma concentrations of these drugs. Following the use of BZDs, a rebound of symptoms of anxiety or panic and withdrawal manifestations can occur. This has been reported to occur even after slow taper of the benzodiazepine use for less than 8 weeks. These effects have been shown to subside in two weeks. In addition, seizures can also be precipitated when discontinuing the drug abruptly. Other side effects associated with this class include dosedependent CNS adverse effects (such as ataxia, somnolence, drowsiness, and dizziness), behavioral changes, hypotension, bradycardia, nausea, anorexia, constipation, diplopia and nystagmus. Most benzodiazepines are pregnancy category X or D and should generally be avoided. See Table 1 for a comparison of BZDs approved for treatment of anxiety. When dosing BZDs, it is important to keep in mind that the smallest effective dose of the medication administered 3-4 times per day should be used. If the medication will be used in an elderly . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Family Practice Newsletter – April 2013 Drug Alprazolam (Xanax ®and Xanax XR) Chlordiazepoxide (Librium ®) Clonazepam (Klonopin ®) Clorazepate (Tranxene ®) Table 1 – Comparison of BZDs Approved for Anxiety Average Dose (Oral) Max Dose Peak Level 2.5-3mg/day in 3 x/day 4 (anxiety) and 10 1-2 hrs IR and 9 divided doses and 3-6 (panic) hrs XR mg daily mg/day 15-100 mg/day in 300 mg/day 1-2 hrs divided 2-4x/day doses 0.5-1 mg/day in divided 4 mg/day 1-4 hrs 2x/day doses (panic) Not indicated for anxiety IR: 7.5-15 mg 2-4x/day 90 mg/day 1-2 hrs Half Life* ~12 hrs (9-20 hrs and 1016 XR hrs) ~15 hrs (7-25 hrs) ~34 hrs (18-50 hrs) Equiv Doses~ 0.5 mg 6-50 hrs 7.5 mg 25 mg 0.2 mg Diazepam 2-10 mg 2-4x/day 30 mg/day 1-2 hrs 20-100 hrs 5 mg (Valium ®) Lorazepam 2-6 mg/day in 2-3x/day 10 mg/day 0.5-1 hr ~15 hrs 1 mg (Ativan ®) doses (8-24 hrs) Oxazepam 10-30 mg 3-4x/day 120 mg/day 2-4 hrs ~5 hrs 15 mg (Serax ®) (3-6 hrs) *Half-life represents drug and metabolites ~Equivalent doses adapted from GlobalRPh’s benzodiazepine dose conversions page available at: http://www.globalrph.com/benzodiazepine_calc.cgi Community Acquired MRSA Cellulitis (CAMRSA) Ryan Hughes, PharmD Candidate Introduction MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is a multi-drug resistant organism that in the past was primarily encountered in the health care setting. Recently, a separate strain of the organism has spread amongst the communities of the United States, and MRSA is now more prevalent than MSSA, with the number of cases estimated to be >60% of the total number of Staphylococcus aureus infections. It is also estimated that between 8-20% of the cases seen in the hospital are CA-MRSA. The CAMRSA variant of MRSA is genetically distinct from the hospital acquired variant, and because of this it is more virulent and tends to spread more readily but is also more susceptible to antibiotic therapy. High-Risk Populations In general, the groups at greatest risk of contracting CA-MRSA cellulitis are those that live in close proximity to each 2 other, typically under conditions that are not completely hygienic and require the use of shared facilities. Some examples include military troops, athletic teams, prisons, and college residential dormitories. A recent study at Ohio University looked at the prevalence of MRSA bacteria on different surfaces within dormitory hall bathrooms with the following results listed on the second table below. These results indicate the need to reinforce good hygiene habits, such as the use of shower sandals, cleaning of mirror shelves before use, regular cleaning of utensils placed on mirror shelves and the use of toilet seat covers. All of these interventions will help minimize skin contact with MRSA surfaces and should reduce infection rates. Recommended Drug Therapy There are several options available for empiric drug therapy, but the use of the various agents depends on the severity of the disease. If it is a localized abscess, then a simple drainage procedure may be all that is required to treat the infection. If the disease appears to be extensive or progressing rapidly, or if the patient has comorbid factors such as DM II or some form of immunosuppression, antibiotics are indicated. The type of antibiotics used depends on suspicion of MRSA or βhemolytic streptococci or both as the suspected pathogen. Typically non- purulent cellulitis will be β-hemolytic streptococci and purulent cellulitis is MRSA. Empiric coverage for MRSA may be required if non-purulent cellulitis fails to respond to therapy, and coverage for both may be considered with signs of systemic toxicity. Clindamycin Resistance The use of clindamycin to treat MRSA has been called into question recently with the increasing prevalence of resistant pathogens. While there are multiple other treatment options with less potential resistance, clindamycin remains a favored agent due to its coverage of both staph and strep, its favorable pregnancy risk category, and its relative cost-profile compared to linezolid. A recent study was undertaken to determine if there were any predictable markers for clindamycin resistance. They found that surgery or previous MRSA infection in the last 12 months or macrolide or clindamycin use within 3 months were significantly associated with clindamycin resistance. Susceptibilities were as follows: doxycycline (97%), TMP-SMX (99%), clindamycin (89.6%). The sample size was 1,026 isolates, and while these results do not preclude the use of clindamycin empirically, they do give some direction for the prescribing physician on patient selection for this agent. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Family Practice Newsletter – April 2013 Drug TMP-SMX Coverage MRSA Adult 1-2 DS tabs BID Pediatric TMP 4-6 mg/kg/dose, SMX 2030 mg/kg/dose BID Notes Preg C/D, not recommended for <2 YO Doxycycline MRSA 100 mg BID ≤45 kg 2 mg/kg/dose BID, >45 kg adult dose Preg D, not recommended for < 8 YO Minocycline MRSA 200 mg x1 then 100 mg BID 4 mg/kg x1 then 2 mg/kg/dose BID Preg D, not recommended for <8 YO Dicloxacillin or Cephalexin Streptococci 500 mg QID Diclox: not for newborns Cephal: not for <1 YO, >15 YO refer to adult dosing Amoxicillin + TMPSMX or tetracycline MRSA + Streptococci Amoxicillin 500 mg TID Diclox: <40 kg 12.5-25 mg/kg/day in four doses, >40 kg 125-250 mg Q6H Cephal: 12.5-25 mg/kg/day Q 12H ≤3 months: 20-30 mg/kg/day in 2 doses >3 months <40 kg: 20100 mg/kg/day in 2-3 doses Clindamycin MRSA + Streptococci 300-450 mg TID 10-13 mg/kg/dose Q6-8H, max 40 mg/kg/day Linezolid MRSA + Streptococci 600 mg BID 10 mg/kg/dose Q8H, max 600mg/dose Higher risk of Clostridium dificile infection >12 YO use adult dosing Osteoarthritis Layomi Fakunmoju, PharmD Candidate Osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive disorder and, its contributory factors include increasing age, obesity, joint trauma and instability and repetitive joint overuse. The most successful treatment programs for patients with OA comprise of a combination of treatments tailored to the patient’s needs, health and lifestyle and the goal of therapy for OA is to improve quality of life, reduce and control pain. These can include exercise, weight control, pain relief techniques, rest, medications, alternative treatments and surgery. These methods are described below. Non-Pharmacological therapy Low impact aerobic exercise programs to lose weight (if overweight) Children >3 months and ≥40 kg, use adult dosing Physical therapy: Range of motion exercises for flexibility and strength training exercise for muscle tone. Occupational therapy: the provision of assistive devices for ambulation such as crutches, cane and other walking aids Use of local heat or cold to the affected joint Manual therapy: Manipulation and stretching joints . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 The Family Practice Newsletter – April 2013 Appropriate footwear and assistance devices for mobility Supports and braces Pharmacological therapy See the table below for a summary of treatment options. Patients who fail Pharmacological and Non-pharmacological therapy: Arthroscopic lavage, debridement and joint replacements. In conclusion, the combination of patient education, exercise, and pharmacologic treatment improves patient outcomes more considerably when compared to pharmacologic treatment alone especially in patients at increased risk, such as, elderly patients, women and patient with previous joint surgery or trauma. Early interventions would improve treatment outcomes and also, better quality of life with patient with OA. Therefore, It is recommended that health care providers provide a treatment combination approach to patients with OA and the method of treatment should also be based on individual preference giving patients the opportunity to make informed decision about their treatment. Drug Acetaminophen (APAP) (Tylenol®) Oral NSAIDs Ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) Naproxen (Aleve OTC or Naprosyn ®) Meloxicam (Mobic), etc. Celecoxib (Celebrex)selective COX-2 Topical NSAIDs Diclofenac (Voltaren) Efficacy Good Limitation Inferior to NSAIDs in efficacy Oral NSAIDS > APAP GI bleed risk Myocardial infarction risk (high dose) except naproxen Comparable to Oral Dermatological side effects More expensive than oral NSAIDS Less side effects than oral NSAIDs Topical (Capsaicin or salicylates) Good efficacy *Salicylatesineffective Good efficacy Burning skin reaction Start with low dose and titrate up Abuse & addiction Opiate-like analgesic Tramadol (Ultram) Glucosamine Good efficacy Abuse & addiction Good efficacy in some patients Conflicting data for efficacy Caution- elderly For patient with severe pain or whom other analgesic are CI Relief of moderate to moderately severe pain. Cause dizziness and somnolence. Adjunctive therapy Use sulfate salt slow onset (2months) Chondroitin Moderate efficacy Mild GI side effects Intra-articular Hyaluronate injectable (Synvisc, hyaluronic acid Hyalgan Intra-articular glucocorticoids inj. Methylprednisolon (Medrol) Triamcinolone (Kenalog10 and 40) Acupuncture Comparable to Oral NSAIDs Very Expensive Mix clinical trial data due to synthesis/formulation Acute knee pain with inflammation Short term relief Adjunctive therapy Can use up to 40mg triamcinolone hexacetonide, injections should not be administered to a single joint more often then once every 3 months No conclusive evidence regarding its effectiveness Can be beneficial to patient with lower bone density because they are at higher risk for OA Short term relief Adjunctive therapy May cause temporary changes in appetite, sleep, and GI Adjunctive therapy Hypercalcemia, malabsorption syndrome, and evidence of vitamin D toxicity Opioids Codeine Vitamin D supplementation 4 All NSAIDs - equal in efficacy Hypercalcemia resulting in HA, N/V, confusion. Bone pain Clinical Pearls Max = 4g for adults and 3g in elderly (liver tox) 1st line High GI bleed risk - PPI or double dose H2 Caution- DM, HTN & CHF Second line. Used in Pts who fails to respond to APAP, conservative tx and who has no Contraindication for use Adjunctive therapy Lack as much evidence as glucosamine Adjunctive therapy Two different formulations approved by FDA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Family Practice Newsletter – April 2013 References: Benzodiazepines and Anxiety 1. Munjack DJ, Crocker B, Cabe D et al. Alprazolam, propranolol, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder and agoraphobia with panic attacks. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1989; 9:22-7. [IDIS 251932] [PubMed 2651490] 2. Davidson JR. Continuation treatment of panic disorder with high-potency benzodiazepines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990; 51(Suppl A):31-7. [IDIS 275894] [PubMed 2258375] 3. Pollack MH. Long-term management of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990; 51(Suppl):11-3. [IDIS 266882] [PubMed 1970813] 4. Pecknold JC, Swinson RP, Kuch K et al. Alprazolam in panic disorder and agoraphobia: results from a multicenter trial: III. Discontinuation effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988; 45:429-36. [IDIS 241071] [PubMed 3282479] 5. Anxiety and Depression Association of America. “Finding Help/ Treatment/ Medications”. Last Updated Unknown. Accessed on 3/12/13. Available online from http://www.adaa.org/finding-help/treatment/medication 6. Lexi-Comp OnlineTM , AHFS DI (Adult and Pediatric) OnlineTM , Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; March 14, 2013 7. Lexi-Comp OnlineTM , Lexi-Drugs OnlineTM , Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; March 14, 2013 Community Acquired MRSA Cellulitis (CA-MRSA) 1. Cadena J, Sreeramoju P, Nair S, Henao-Martinez A, Jorgensen J, Patterson J. Clindamycin-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiologic and molecular characteristics and associated clinical factors. Diagnostic Microbiology And Infectious Disease [serial online]. September 2012;74(1):1621. Available from: MEDLINE with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 17, 2013. 2. IDSA Guidelines: Catherine Liu, Arnold Bayer, Sara E. Cosgrove, Robert S. Daum, Scott K. Fridkin, Rachel J. Gorwitz, Sheldon L. Kaplan, Adolf W. Karchmer, Donald P. Levine, Barbara E. Murray, Michael J. Rybak, David A. Talan, and Henry F.Chambers Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections in Adults and Children Clin Infect Dis. first published online January 4, 2011. Accessed March 17, 2013. 3. Tonn K, Ryan T. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in college residential halls. Journal Of Environmental Health [serial online]. January 2013;75(6):44-49. Available from: MEDLINE with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 17, 2013. Osteoarthritis References 1. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: The care and management of osteoarthritis in adults 2. American college of Rheumatology Osteoarthritis management guidelines: www.rheumatology.org 3. Arthritis Foundation: www.arthritis .org 4. American Geriatrics Society: www.americangeriatrics.org 5. Brasington R, Hsia EC, O’Hanlon KM, Murray JL eds. Osteoarthritis. Maryland Heights, Missiouri, 2010. MD Consult. 14 March. 2013. Retrieved from<http: //www.mdconsult.com>. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5