The Hero Twins

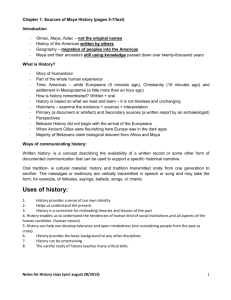

advertisement