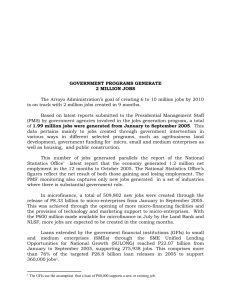

5 - UN Millennium Project

advertisement