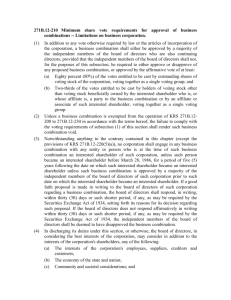

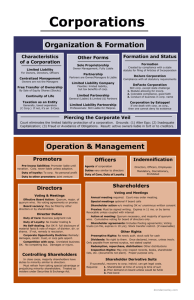

Corporations I

advertisement