lovit-alex-13.06.11

advertisement

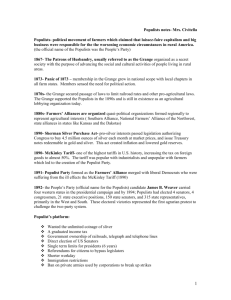

Kettering Foundation TO: Civic Renewal Stock-Taking Group FROM: Alex Lovit DATE: June 11, 2013 SUBJECT: Civic Renewal in the Populist Movement CC: The Populist Movement as Civic Renewal As a broad historical term, “populism” refers to an economic and political reform movement of American farmers in the late 19th century, who sought to protect their own economic position through collective action and political organizing. Many scholars have interpreted the populist movement as a robust democratic crusade, as rural reformers united to fight against market forces that they found exploitative (including monopolistic railroad corporations and capricious commodity markets) and political traditions they perceived as undemocratic (such as the entrenchment of the two major parties and systems of political patronage). Historians have often imbued their accounts of populist communities with a certain degree of romance. “How is a democratic culture created?” Lawrence Goodwyn asked. “Apparently in . . . prosaic, powerful ways. When a farm family’s wagon crested a hill en route to a [Farmers’ Alliance] encampment and the occupants looked back to see thousands of other families trailed out behind them in wagon trains, the thought that ‘the Alliance is the people and the people are together’ took on transforming possibilities. Such a moment . . . instilled hope in hundreds of thousands of people who had been without it.”1 On a more practical level, populism operated through a series of agrarian organizations. The most prominent of these were the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, which peaked in the 1870s, and the Farmers’ Alliance, whose membership rolls expanded rapidly during the 1890s. The Grange and the Alliance were both complex and somewhat decentralized organizations, and provided a variety of services to their constituents: a venue for socializing; educative programs on farming techniques, and on economic principles; and cooperative economic ventures, including both cooperative stores and collective marketing efforts. Some of these programs proved to be unstable (cooperative store and collective marketing campaigns were often particularly short-lived), but the Grange and the Alliance did provide the opportunity for hundreds of thousands of farmers to collectively consider their shared interests, and the measures they might take to solve their shared problems. During the 1890s, populism increasingly turned toward governmental solutions to these problems; the platform of the People’s Party called for radical reforms, including federalization of railroad companies, the introduction of a progressive income tax, and a federal program to provide low-cost crop storage and low-interest loans to farmers. But like the Grange and Alliance that had preceded it, the People’s Party also proved short-lived; after 1896, the party rarely nominated independent 1 Lawrence Goodwyn, The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 34. candidates, instead promoting “fusion” candidates with the Democratic Party. By the turn of the 20th century, both the collective and political efforts of the populist movement had declined precipitously. The Rise and Fall of Populism As this brief history demonstrates, the populist movement was unstable even during the height of its national power. Within a single generation, populism had swelled into a national movement, cycled through the rise and fall of three distinct organizations (the Grange, the Farmers’ Alliance, and the People’s Party), and then declined altogether. In some ways, the fortunes of the populist movement were bound up in the industrializing economic trends of the period, during which the portion of the American labor force working in agriculture fell into the minority for the first time in the nation’s history—declining from 53% in 1870 to 31% in 1910.2 Certainly these demographic shifts might explain the failure of the agrarian People’s Party to capture national majorities, but this is an incomplete explanation of why the movement failed to maintain its cooperative economic and educative programs. How did the populist movement so quickly organize the collective efforts of hundreds of thousands of farmers across the nation, and just as quickly devolve into inactivity? Historians provide various explanations for populism’s decline. Some suggest that the wealthier leadership class of populist organizations pursued interests at odds with the goals of rank-andfile members. For example, the Indiana state Grange shut down its cooperative purchasing agency in 1876, despite the agency’s successes in providing Grange members with supplies and groceries at discounted prices. The agency was shuttered apparently out of concern that this statewide wholesale operation harmed local town economies, in which many elite Grange leaders were deeply invested.3 Some historians argue that the movement’s increasingly political nature similarly reflected a misalignment between the goals of leaders and of members: “A political elite tried to use the [Southern Farmer’s Alliance] as a vehicle for political advancement. But political lobbying did not offer any promise [to address] . . . the issues that concerned members.”4 Lawrence Goodwyn argues that populism’s downfall was its turn toward Populist/Democratic fusionist campaigns, which set a precedent for “narrowed boundaries of modern politics . . . encircl[ing] . . . the relationship of corporate power to citizen power [and] the political language legitimized to define and settle public issues.”5 In other words, as the populists abandoned citizen-centered methods to pursue a more traditional electoral approach, they accepted the basic legitimacy of nation’s current economic system, and limited individual citizens’ involvement to the act of voting. Indeed, as the Populist Party became the dominant populist organization in the 1890s, the Farmers’ Alliance shrunk, and discontinued previous educational programs. Theodore Mitchell points to one telling detail from the Populist Party’s 1892 campaign, when the Southern Farmers’ Alliance’s official organ, The National Economist, replaced its recurring “Educational Exercises” feature with political reporting. “Perhaps no other 2 Bicentennial Edition: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Part I (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1975), 139. 3 See Glenn P. Lauzon, Civic Learning through Agricultural Improvement: Bringing “the Loom and the Anvil into Proximity with the Plow” (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2011), 123-150. 4 Michael Schwartz, Naomi Rosenthal, and Laura Schwartz, “Leader-Member Conflict in Protest Organizations: The Case of the Southern Farmers’ Alliance,” Social Problems 29 (1981), 31. 5 Goodwyn, Populist Moment, 265. 2 single act better captures the shifting priorities of the National Alliance than the substitution of campaign news for the Exercises,” Mitchell writes. “In a stroke, the national leadership moved political education, long the guiding star of the Southern Alliance, to the background, replaced by the tactical demands of winning an election.”6 If this was the strategic shift that led to the downfall of the populist movement, it was not an entirely intentional one. As Robert McMath points out, “The Alliance had always been an educational institution,” and the leaders pushing the movement into national politics “agreed on the need for a more organized and sophisticated educational program.”7 The Populist Party saw its political organizing as an extension, rather than a repudiation, of the Alliance’s educational programs. But despite these intentions of continuity, political organizing could never be as open-ended as the collective action supported by the Grange and the Alliance. As Theodore Mitchell writes, “The more they became focused on partisan politics, on winning elections, the less the movement’s leaders concerned themselves with the maintenance of the [movement] and its culture.” In the end, populist supporters were reduced to a more passive role—“a constituency instead of a movement.”8 What Lessons Can We Learn from Populism? Some authors have disputed this narrative of populism as lapsing from civic action into political compromise and inactivity. Charles Postel’s influential account of the movement contends that populists were quintessentially modern from the start, embracing “centralized direction, rapidly coordinated communications, bureaucratic organization, and salaried agents and lobbyists,” and modeling their political activities after the “the bankers, manufacturers, railroad companies, and cattle dealers, all of whom understood the need to unite their separate and distinct organizations for their common interest.”9 In this view, the populists represented less a civic movement than an interest group. But even if the populists were primarily motivated by self-interest, the movement still represented a broad-based coalition of engaged citizens. As Postel himself points out, “The demise of Populism constricted the social base of reform. Instead of farmers, coal miners, and other poorly educated women and men gathering in lodges and meeting halls for self-education and self-mobilization, the initiative passed to expert women and men, with professional training and administrative posts.”10 Perhaps Postel’s interpretation should be reason for celebration rather than cynicism; his account indicates that civic renewal movements can spring from the simple desire to better one’s own condition and those of one’s neighbors. And if the populists constructed large, bureaucratic organizations, they also left room for the smaller scale of the classroom and the camp meeting, where farmers could recognize and discuss their common concerns. In any case, many of populism’s successes were attributable to these bureaucratic institutions; national educational programs, cooperative stores, and political campaigns alike require some degree of centralized direction. If populism had remained entirely local and decentralized, it might not have had so large an impact, or inspired such a large body of historical literature. 6 Theodore R. Mitchell, Political Education in the Southern Farmers’ Alliance, 1887-1900 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 169. 7 Robert C. McMath, Jr., American Populism: A Social History, 1877-1898 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), 148. 8 Mitchell, Political Education, 16. 9 Charles Postel, The Populist Vision (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 104, 140. 10 Postel, Populist Vision, 286. 3 The question that remains, and one which populism’s decline does not conclusively answer, is how to balance these varied demands. When populist organizations functioned best (and attracted the most members), they provided both space for local discussion and centralized coordination, and promised both self-improvement and governmental reform. The instability of populist organizations demonstrates the difficulty of maintaining this balance (and fulfilling these promises). But over the course of several economically tumultuous decades, populism did succeed in attracting hundreds of thousands of supporters from across the country, and engaging them through both collective action and political organizing. And although the organizations most often identified with populism (the Grange, the Farmers’ Alliance, and the People’s Party) all declined before the turn of the century, many of the populists’ ideas lived on, finding new supporters during the progressive era. Several of the measures advocated by populists came to fruition in the early 20th century—including the federal income tax, increased railroad regulation, restrictions on immigration, the direct election of federal senators, and agricultural subsidy programs. As Postel puts it, “Populism proved far more successful dead than alive.”11 If there was a tragedy to populism’s decline, it was not in the failure to achieve goals, but rather the loss of a broad civic movement. 11 Postel, Populist Vision, 271. 4