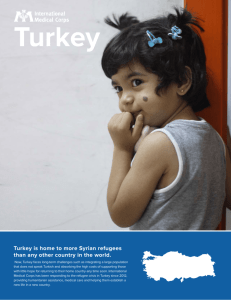

Gay refugees in limbo in Turkey

advertisement

http://www.thestar.com/news/article/890453--gay-refugees-in-limbo-in-turkey?bn=1 Gay refugees in limbo in Turkey November 13, 2010 David Graham Farzan Shahmoradi walks the hills overseeing Van, Turkey, where he was granted temporary asylum after fleeing Iran, where we was forced to hide his sexuality. VAN, TURKEY—From the passenger seat of a white minivan, Farzan Shahmoradi stared out the window, still unsure whether he had crossed the border. They countryside, all hills and rock and bushes, looked the same. Then, as the van rounded a bend, Shahmoradi’s smuggler pointed to an enormous flag — a white crescent moon and star on a red background — flapping on a hilltop. He was in Turkey, but he was far from safe. He still had to get to the United Nations refugee agency without attracting the attention of Turkish police, who could deport him if they knew he had no passport. For three days, Shahmoradi had entrusted his life to smugglers, paid the equivalent of $1,400 U.S. to secret the gay man across the border to Turkey. In the eastern city of Van, about 100 kilometres from the border, Shahmoradi went straight to the apartment of another gay Iranian refugee who agreed to put him up. He hid out for two days, waiting until he knew a Farsi interpreter would be on duty at the agency, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees or UNHCR. After a lifetime of hiding his sexuality, Shahmoradi, 30, had to convince a stranger he was gay and explain what would happen if he was sent back to Iran. An insular Muslim country, Iran’s sharia laws are based on a strict interpretation of the Qur’an. Sex between anyone other than a husband and wife is a sin, and homosexuality is a crime punishable by death. Shahmoradi had heard about two teenagers, believed to be a gay, hanged in the holy city of Mashhad in 2005. He had seen pictures of masked executioners fitting nooses around their. The next frame showed their bodies dangling from ropes in the middle of a street. Although most Iranians, including refugees, can travel to Turkey on a valid passport, Shahmoradi's had expired. He told the UN officer he was ordered to report to court when he tried to renew it. Shahmoradi had been ignoring repeated requests to come in for questioning after he and a friend were arrested for playing loud music in a car. Now he started to think about leaving. He already had a record. He was just 19 when police raided a gay party and took him to a Tehran prison, where he spent six terrifying nights. Shahmoradi feared this second brush with the law could result in much stiffer punishment, such as flogging or imprisonment, especially if the judge knew he was gay. People like Shahmoradi don't need to have a death warrant in their hands to seek asylum in Turkey, says Brenda Goddard, an officer at the UNHCR in Ankara. “We simply want to know why they left and what will happen if they return.” The UNHCR is a key player in the protection of refugees who come to Turkey from non-European countries, most of whom enter legally with passports by train, plane or bus. In the case of gay refugees from Iran, they help get temporary asylum in Turkey and refer their cases to countries that sponsor refugees. The three that accept more cases out of Turkey all together than others are the United States, Canada and Australia. The acceptance rate for refugees from Turkey is quite high at about 60 per cent, says UNHCR external affairs officer Metin Corabatir. At the agency office in Van, Shahmoradi registered as a refugee and was told to remain in Van and report to local police a couple of times a week. He had nothing but a black nylon backpack filled with two shirts and a pair of jeans, and the equivalent of $350 U.S. in his pocket. Shahmoradi was free to go, but faced a long wait. He still had to have his determination interview, where the UNHCR would decide if he was a refugee. And then he would have to wait to see whether Canada would sponsor him. He told his UNHCR officer looking after his case he wanted to move to Canada. Like many gays, lesbians and transgendered people leaving Iran, he knew it as a liberal country with a universal health-care system, where gay marriage is legal. He also requested it because of an aunt who lives there, and his connection to Parsi. The UNHCR acknowledges wait times are too long and officials there are optimistic that an infusion of money from the U.S. will help them hire more legal officers to handle the caseload. IT WAS OCTOBER 2007 , and Shahmoradi was just 30. He stayed in Van for 14 months, living on the $200 U.S. a month his doting father was sending from home. That was enough to live cheaply, rent a room in a shared apartment and buy groceries, but there was no money left over for extras like eating out and new clothes. Shahmoradi moved frequently, and once landed a job in a clothing store. That lasted 10 days. Since 2006, Turkey has allowed refugees to work, but in a country with unemployment hovering around 11 per cent, jobs are scarce. “It has made it difficult for employers who have to verify the same job cannot be done by a Turkish citizen,” said the UNHCR's Goddard. “So people work in the secondary economy.” Roodabeh, 32, earned about $1,000 a month as a cardiac nurse at Dey Hospital in Tehran. In the Turkish city of Kayseri, she worked two jobs washing dishes. At Taj Salon restaurant, she worked seven days a week and was paid about 80 cents an hour. “We are easy targets for exploitation,” said the lesbian, who fled Iran almost three years ago. “Complain and you're fired.” Some just watch television — BBC in Farsi out of London, or the Persian bureau of the Voice of America as well as state-regulated channels from Iran, Iranian music and entertainment channels from California and a Persian music channel out of Dubai. They walk to the police station, buy groceries, wait for news. Some even try to sleep the day away, just to pass the time. Shahmoradi was assaulted in the streets by Turkish tormentors. They held him down on the ground and burned a hole in the back of his hand with a piece of coal, which is used to heat homes. Because he did not feel safe in Van anymore, he asked if he could move to Gaziantep, one of the 30 or so towns approved by the Turkish government for refugees. A former manager of an Internet café, Shahmoradi was online a lot, visiting gay chat rooms and looking for love. That’s where he met Davut, a Turkish man who lived in Gaziantep. After a month, they moved in together. But when Davut was called for military service and stationed in Van, Shahmoradi moved there too, without telling the UNHCR or Turkish authorities. Shamoradi would live to regret the move, but at the time he didn’t care. He had never been happier. Back in Van, he shared an apartment with four Baha’i refugees, a religious minority persecuted by the Iran government. He and Davut met on his days off, but the rest of the time Shahmoradi spent surfing the web, watching TV and keeping a low profile. For the three years Shahmoradi was in Turkey, he was in regular contact with Arsham Parsi in Toronto, the founder of the Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees and the man who helped him flee Iran. Shahmoradi asked Parsi for advice, and for money when he was short. Parsi travels to Turkey several times a year to meet his contacts at the United Nations, plead cases for refugees he has helped get to Turkey and check up on others, like Shahmoradi, who have been waiting for months, sometimes even years, for a country to call home. AS SOON AS PARSI landed in Istanbul in September, his cellphone started to ring. Parsi, 30, received a stream of texts written in Pinglish — Farsi, or Persian, words written in the Roman alphabet. In Toronto, Parsi is one of many immigrants who live on welfare in public housing. But in Turkey, he's a celebrity. People have heard him interviewed countless times by Voice of America and the BBC. At a restaurant, a waiter married to a transgendered woman instantly recognized Parsi and politely asked if he would help the couple get out of Turkey. Parsi finds apartments, connects roommates, and helps newcomers fill out forms. He tells them about life in Canada. He even instructs them on how to behave during the all-important interview with a legal officer at the UNHCR. In the five years since he fled Tehran for Turkey, Parsi has helped 50 people relocate to Canada. He is working on the cases of another 250 people, some as far away as Thailand, Syria, Malaysia, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Most of them are in Turkey. Turkey, however, is a reluctant host. Its unique geography makes it a gateway, a way station for thousands of people who pour across its eastern borders from Muslim nations such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia in an effort to get to Europe in the west. The Turkish government hopes its generosity will help its case for inclusion in the European Union. A NATO member with noncombat troops in Afghanistan, it wants a reputation as a responsible, hospitable neighbour. The country provides temporary asylum — a limbo at best — and charges some of the most marginalized people on earth a $200 residence fee every six months, a levy the Turkish ministry of interior is working with local authorities to waive. Although it is more permissive than Iran, Turkey is still a Mulsim country and homophobia, particularly in the small cities where most gay asylum seekers are sent to live, is overwhelming. The UNHCR offices receive complaints about discrimination and insults by Turkish residents, made worse by unsympathetic police. They get reports from gay and lesbian refugees complaining about “small shop keeps who won’t sell things to them,” according to the UNHCR’s Corabatir. About 200 Iranians cross the border into Turkey each month, each seeking asylum at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Among them are persecuted religious groups like the Baha’i, Muslims who have recently converted to Christianity, political protesters as well as gay, lesbian and transgendered people. FOR PARSI , getting out of Iran alive is all that matters and he instructs refugees to follow the rules. But Shahmoradi has already broken one of Turkey’s by moving back to Van without permission. “I always warn them not to fall in love while they’re in Turkey,” said Parsi. “Don’t make any plans. Concentrate on getting out.” He thinks fear makes them seek out emotional support. “They feel free in Turkey and they want to experience love maybe for the first time.” Parsi understands, but still thinks it was foolhardy for Shahmoradi to followed Davut to Van last spring. It’s unlikely Shahmoradi would be deported if caught living outside Gaziantep, Parsi said. But he could have been sent back, fined, and ordered to check in with local police daily. Ten months ago, Shahmoradi was told Canada would sponsor him as a refugee. He had to make plans to leave the country that had become a home away from home, a place where he was able to have his first real gay relationship. Shahmoradi had mixed emotions. Life was certainly better in Turkey than it was in Iran. He felt safe. And he was in love. When his boyfriend stole away from military duties to say goodbye, perhaps for the last time, Shahmoradi couldn’t contain his delight at seeing Davut again and hold back the sadness at leaving his love behind. Shahmoradi held tight to Davut’s hand and stroked his shoulder. He whispered something in his ear — part Turkish, part Farsi —that made him smile. They talked about how they met a year earlier in an online chat room, attracted because they were not interested in a one-night stand. They both wanted something permanent. As he was about to board the plane from Van to Ankara, Shahmoradi was stopped. His documents showed he wasn’t supposed to be in Van and staff refused to let him through. Shahmoradi shrugged his shoulders and seemed calm considering the setback. The next day, Shahmoradi asked police in Van for permission to take a bus to Gaziantep, where he would get an exit permit to leave the country. From there, he took the bus to Kayseri, where he met up with Parsi for the trip to Istanbul. There they would catch a plane for Frankfurt, with a connection to Toronto. Shahmoradi called Davut over and over again, frantically asking him whether he should get on the plane. Davut told him to think of the bigger picture, to think of their future. Shahmoradi was late for his flight, arriving just before takeoff. He forgot his travel documents on an airport chair while he went for a walk. Parsi tailed him, checking and double-checking to make sure he didn’t lose the papers that would allow him to leave the country. As he turned off his cellphone, ending a stream of panicked calls to Davut in Van, Shahmoradi fell silent. It was night, and as he settled into his seat, Shahmoradi still was not sure he had made the right decision.