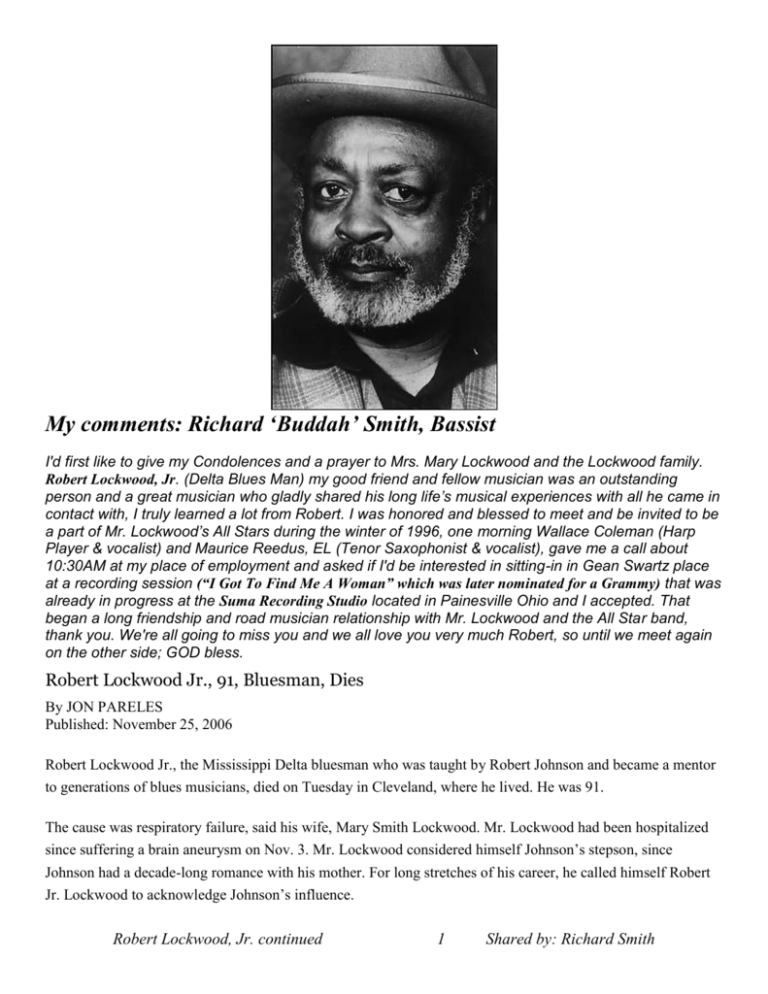

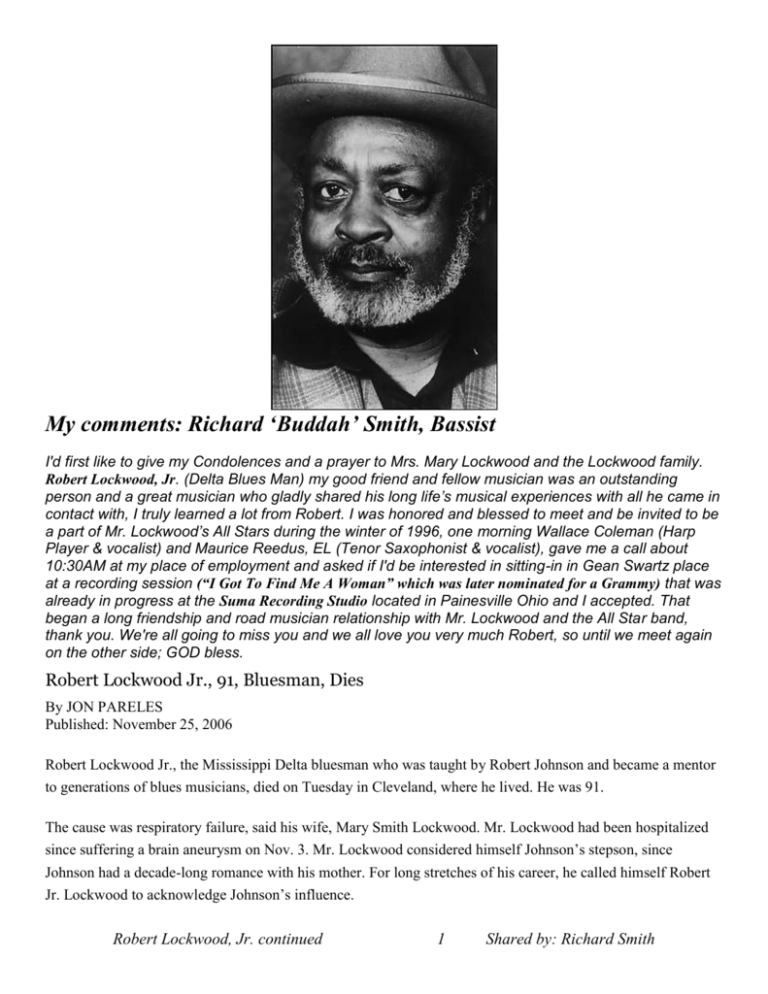

My comments: Richard ‘Buddah’ Smith, Bassist

I'd first like to give my Condolences and a prayer to Mrs. Mary Lockwood and the Lockwood family.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. (Delta Blues Man) my good friend and fellow musician was an outstanding

person and a great musician who gladly shared his long life’s musical experiences with all he came in

contact with, I truly learned a lot from Robert. I was honored and blessed to meet and be invited to be

a part of Mr. Lockwood’s All Stars during the winter of 1996, one morning Wallace Coleman (Harp

Player & vocalist) and Maurice Reedus, EL (Tenor Saxophonist & vocalist), gave me a call about

10:30AM at my place of employment and asked if I'd be interested in sitting-in in Gean Swartz place

at a recording session (“I Got To Find Me A Woman” which was later nominated for a Grammy) that was

already in progress at the Suma Recording Studio located in Painesville Ohio and I accepted. That

began a long friendship and road musician relationship with Mr. Lockwood and the All Star band,

thank you. We're all going to miss you and we all love you very much Robert, so until we meet again

on the other side; GOD bless.

Robert Lockwood Jr., 91, Bluesman, Dies

By JON PARELES

Published: November 25, 2006

Robert Lockwood Jr., the Mississippi Delta bluesman who was taught by Robert Johnson and became a mentor

to generations of blues musicians, died on Tuesday in Cleveland, where he lived. He was 91.

The cause was respiratory failure, said his wife, Mary Smith Lockwood. Mr. Lockwood had been hospitalized

since suffering a brain aneurysm on Nov. 3. Mr. Lockwood considered himself Johnson’s stepson, since

Johnson had a decade-long romance with his mother. For long stretches of his career, he called himself Robert

Jr. Lockwood to acknowledge Johnson’s influence.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

1

Shared by: Richard Smith

Mr. Lockwood carried the music of the Mississippi Delta to other emerging blues scenes. He performed on the

pioneering blues radio show “King Biscuit Time.” He gave B. B. King guitar lessons. He became a studio

musician at Chess Records and played on sessions that defined electric Chicago blues and went on to shape rock

’n’ roll. Although he could play in the old Delta style, he embraced blues from across the United States and

drew strongly on the harmonies and phrasing of jazz.

“I never did want to sound like anybody else,” he said in a 2001 interview with the Big Road Blues Web site.

“What I play sounds easy, but you just try it. It’s not easy.”

Mr. Lockwood was born on March 27, 1915, in Turkey Scratch, Ark. He learned to play the family pump organ

and hoped to become a pianist. But when he was a teenager, Robert Johnson moved in with his mother (who

was separated from Robert Lockwood Sr.). Once Mr. Lockwood heard Johnson’s music, he turned to guitar.

Other bluesmen worked in guitar duos, but “Robert came along and he was backing himself up without anybody

helping him, and sounding good,” Mr. Lockwood recounted in Robert Palmer’s 1981 book, “Deep Blues.”

Johnson was secretive about his technique, but he instructed Robert Jr. in his songs and his guitar style. “Robert

wouldn’t show me stuff but once or twice,” Mr. Lockwood said, “but when he’d come back I’d be playing it.”

When Johnson was killed in 1938, Mr. Lockwood was so shaken that he didn’t perform for a year. “Everything

I played would remind me of Robert, and whenever I tried to play I would just come down in tears,” he said.

Mr. Lockwood often insisted that he improved on what he learned from Johnson. “On a lot of things, you know,

Robert kind of messed the time around, and I played perfect time,” he said.

In 1940, Mr. Lockwood traveled to Chicago, and in 1941 he made his first recordings in nearby Aurora, Ill. But

that year he returned to the Delta, where he and Rice Miller (calling himself Sonny Boy Williamson)

inaugurated a daily blues radio show, “King Biscuit Time,” on KFFA in Helena, Ark. It made them stars across

the South.

Growing up in Mississippi, a young B. B. King heard Mr. Lockwood on the radio and went to him for guitar

lessons, and Mr. Lockwood worked with Mr. King in the late 1940s. In interviews, he said that while Mr. King

was already a skilled guitarist, his timing was bad.

Mr. Lockwood settled in Chicago in the early 1950s and became a mainstay of the studio bands at Chess

Records and other labels. Although he recorded a few singles of his own, he worked primarily as a sideman. He

backed Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Sunnyland Slim and Little Walter, among many others, and was in the

pianist Roosevelt Sykes’s live band. In 1960 he accompanied Muddy Waters’s pianist, Otis Spann, on the duet

album “Otis Spann Is the Blues.” As the 1960s began, Mr. Lockwood moved to Cleveland, where he reigned as

the city’s leading bluesman. He resumed his solo recording career in the 1970s with albums for the Delmark

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

2

Shared by: Richard Smith

and Trix labels, drawing on blues, jump blues and swing styles from across the country. He also recorded live

albums in Japan.

Around 1975, his first wife, Annie Roberts Lockwood, gave him a 12-string guitar, and he made it his main

instrument, switching from the six-string. He is survived by his second wife and nine children.

Mr. Lockwood reunited with an old Delta partner, Johnny Shines, on albums for Rounder Records as the 1980s

began. Their album “Hangin’ On” was named best traditional blues album at the first Blues Music Awards in

1980. Mr. Lockwood’s 2000 album “Delta Crossroads” (Telarc) received the same award. Mr. Lockwood was

inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1989.

In the ’80s, Mr. Lockwood made albums of Robert Johnson songs, and in the ’90s he started his own label,

Lockwood Records, which released “What’s the Score.” In 1995 he received the National Heritage Fellowship

Award, America’s most prestigious traditional arts award. He toured the worldwide blues circuit.

Until Nov. 1, Mr. Lockwood worked a weekly club gig at Fat Fish Blue in Cleveland. A street in Cleveland’s

night-life area, the Flats, was named for him in 1997. Verve Records released his album “I’ve Got to Find Me a

Woman,” on which B. B. King and others sat in, in 1998. It was nominated for a Grammy Award, as was “Delta

Crossroads.”

“I just do what I’m doin’,” Mr. Lockwood told Living Blues magazine in 1995. “Express my ideas, explore new

ideas.”

Robert Lockwood Jr. Expanded The Spectrum of the Blues

By Terence McArdle

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, November 23, 2006; Page C01

I once asked the great bluesman Robert Lockwood Jr., who died Tuesday at age 91, for guitar lessons. It was

1986. I was 25, and it took all of my youthful gumption to do it. A few minutes earlier, I had just witnessed

Lockwood dismissing a man who requested an interview.

"I've been recording since 1941," he said. "I don't need the publicity."

On that summer day, Lockwood was standing in the hot sun beside an outdoor concert stage at the Prince

George's Equestrian Center; a chain-link fence separated him from his fans. I told Lockwood that I wanted to

learn to fingerpick. I had family in Toledo and could drive out to his home in Cleveland to take lessons. Did he

ever give guitar lessons?

"Sure, I've taught guitar. I taught Louis Myers, Luther Tucker, M.T. Murphy, B.B. King," he said, managing to

give me the polite brushoff and establish his credentials at the same time.

"Tell you what," he said. "You go to a music store and learn classical guitar. Then you can play any type of

music."

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

3

Shared by: Richard Smith

I was dumbstruck. Classical guitar? That suggestion could have come directly from my mother's mouth. It

seemed a world apart from Lockwood's own background, but he always liked to defy expectations.

Among the giants of Delta and Chicago blues, Robert Lockwood Jr. may have been the last of the greats, having

outlived Muddy Waters, Jimmy Rogers and John Lee Hooker.

He learned at age 11 directly from the itinerant blues singer Robert Johnson, who had become romantically

involved with Lockwood's widowed mother in Helena, Ark. By 15, Lockwood was playing juke joints and fish

fries throughout Mississippi and Arkansas with Johnson.

One legend from those days has him playing a fish fry on one side of the Sunflower River, with Johnson on the

other bank. The audience could not tell which guitarist was Johnson.

If Lockwood lacked the fame of Waters or Hooker, it was only because so much of his time was spent as a

sideman for other blues singers. Until the late 1970s, his recordings as a singer and bandleader were sporadic.

Lockwood rightly considered himself an innovator. His 1950s recordings as the guitarist for Little Walter and

the Jukes created an entirely new sound, bridging the gap between country blues and urban jump blues. Little

Walter's amplified harp would fill a room with dazzling swing riffs that Lockwood would answer with sliding

jazz chords and quick fills. Drummer Fred Below propelled the band by dropping bombs -- snare accents on the

off beat -- while second guitarist Louis Myers added his steadying touch substituting for a string bassist. On the

strength of such recordings as "My Babe" and "Off the Wall," they toured the country and played the Apollo

Theatre in Harlem.

In later years, Lockwood became a mainstay of blues festivals. I've lost count of how many times I saw him

perform (at least a dozen) but every time I watched his fretwork with awe and envy.

Performing as a soloist, Lockwood could take apart a classic piano piece like "Cow Cow Blues" or "Pinetop's

Boogie Woogie" and flawlessly re-create both the left- and right-hand parts on the guitar. It was an approach

that harked back to such greats of the 1920s and 1930s as Big Bill Broonzy and Hacksaw Harney -- an era when

the guitar or the piano could be the entire band. At this type of fingerpicking, Lockwood was the last master of

his generation.

Question-and-answer sessions often followed performances at festivals, and at one, a long-haired fan in a tiedye shirt and jeans asked him if you had to live the blues to sing it.

"No," he answered, then paused. "If you lived the blues, you'd be dead."

It was a typical Lockwood response: witty and laconic. Most of his audiences were a generation, a race and a

world removed from his and Robert Johnson's experience as impoverished African Americans in the Jim Crow

South. If Lockwood seemed happiest playing Johnson's music, he often felt obligated to tell these earnest new

fans that Johnson did not sell his soul to the devil at the crossroads, as myth had it.

As an admirer of Chet Atkins, Lockwood often played a Gretsch Country Gentleman, an electric guitar that

carried Atkins's endorsement. In the 1970s, he started playing a 12-string model with a very bright tone -- an

odd choice for a blues guitarist, but one that probably suited his deep-seated desire to play against the audience's

expectations. In fact, if you ever asked him, Lockwood would tell you that he considered himself a jazz

guitarist. He threw in an occasional bebop chord substitution and drove the band with an unerring sense of

swing. But it was still blues.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

4

Shared by: Richard Smith

Some years after I approached Lockwood about guitar lessons, I found myself in Cleveland playing a wedding

gig as guitarist for the Uptown Rhythm Kings. The people were wealthy enough to have two bands on the bill;

the Lockwood Allstars were the other band. The reception was in one of those old private clubs with cloth hand

towels in the restrooms and beautiful wood furniture that had begun to chip around the edges.

Our band arrived after a six-hour drive from Baltimore, and we were shown to one of two conference rooms

that were to serve as makeshift dressing rooms. Lockwood arrived with his wife, Annie. She took one look at

our singer Eric Sheridan catnapping on the floor and a pile of suit bags strewn across the conference table.

"Where's the dressing room?" she asked. Always one to protect her husband's interests, she was clearly ready

to make a scene. But Lockwood grasped that we had come a long way to do a job and he didn't want to wake

our sleeping singer.

"Leave it lay, Annie, leave it lay," he said.

Then he looked at me and jokingly asked if I could give him guitar lessons. My idol remembered me from that

day years ago.

I never did heed Lockwood's advice to take classical lessons, though. The best lessons were watching the master

play his blues.

Robert Lockwood Jr., blues icon, dies at 91

Clevelander's career spanned seven decades

By Malcolm X Abram

Beacon Journal staff writer

Robert Lockwood Jr., one of the few remaining authentic Delta Blues guitarists, who settled and became a

beloved and respected icon in Cleveland, has died.

Lockwood, 91, died Tuesday of respiratory failure at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, according to

spokesman George Stamatis. He had been a patient since suffering a stroke Nov. 3.

Lockwood was one of the few people on the planet who knew and learned guitar from blues icon Robert

Johnson -- he was briefly involved with Lockwood's mother. But Johnson was only the first among many blues

icons with whom Lockwood would cross paths.

During his more than seven-decade career, he played, recorded and rubbed shoulders with many of the genre's

greats, particularly during the 1950s, when, as a session player for the legendary Chicago-based blues label

Chess Records, he backed up Little Walter, Sunnyland Slim and Roosevelt Sykes. Longtime friend and former

protege B.B. King returned the favor by recording some duets on Lockwood's 1998 album I Got to Find Me a

Woman.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

5

Shared by: Richard Smith

Lockwood never received the national fame or wealth of his guitar-playing friend or some of his

contemporaries, but he was well known and highly respected among blues fans, who admired his playing on

classic songs such as Sonny Boy Williamson II's Don't Get Me to Talking.

When rock 'n' roll became the sound of popular music, Lockwood took the advice of his colleague and frequent

visitor Williamson and moved to Cleveland in 1960, where he supported his family by working various odd

jobs between gigs in local clubs, and mentored countless area blues men.

``It's a tremendous loss, a hole that can't be filled. He cannot be replaced,'' said Bill Miller, a harmonica player

known as ``Mr. Stress,'' who first met Lockwood in the 1960s.

``Musically, he was a pivotal figure, in the history of the music straddling the line between Robert Johnson and

the modern blues guitar style, though he also took great pride in his ability to play jazz,'' Miller said.

``Personally, he had a wicked sense of humor and he had a strong sense of dignity and who he was. God bless

him that at 91 he was still able to play, and there's no way that a musician can go any better than playing up

until the end.''

Colin Dussault was an underage, aspiring musician in 1985, when he used to sneak into Brothers Lounge to

hear Lockwood play. After Dussault started his own band in 1989, he and Lockwood would often cross paths

after gigs, and Dussault would buy the legend breakfast.

``He'd always order steak and shrimp, the most expensive thing on the menu,'' Dussault said, chuckling.

``We'd sit there for hours and he'd tell stories about Sonny Boy Williamson and Willie Dixon and all the Chess

Records people. As an 18-year-old aspiring musician, you can read and watch movies, but to sit across a table

and talk to someone who knew these people, it's an education you can't get anywhere else.''

Lockwood actually quit playing music a few times in his life, most recently in 1974, because ``I just got tired of

playing,'' he told the Beacon Journal in 2005. ``I got tired of no-playing musicians, but what keeps bringing me

back is people keep offering me more money.''

But it wasn't just the fact that he was making more money than he ever expected from being a ``blues player''

``I feel like I'd be cheating the people, and I say when you get to be a musician -- a full-time traveling musician

-- you owe it to the public to get out there,'' he said.

In the 1980s, Lockwood's longevity and continued music-making began to garner him awards. He was inducted

to the Blues Hall of Fame in 1989, received the National Heritage Fellowship Award from Hillary Clinton in

1995, and had a street in Cleveland's Flats named for him. Lockwood, like his old friend and fellow

nonagenarian Henry Townshend, who died in September, was truly one of the last great bluesmen. Through his

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

6

Shared by: Richard Smith

playing, singing and willingness to share his knowledge and storied history with other musicians, he was a

direct flesh-and-blood conduit to a time and a culture exists now only in the laser-guided grooves of CD box

sets and the grainy footage of blues documentaries.

In the coming weeks, there will surely be several musical tributes to Lockwood that will find area blues

musicians vying for a chance to pay their own tribute to their friend and mentor through their music.

``He had some good paydays and thank God he lived as long as he did to collect some of the dues that he paid,

because he sure as hell paid them,'' Miller said.

``There's a hole in the city that won't be filled -- there's nobody around that can fill that hole.''

Malcolm X Abram can be reached at 330-996-3758 or mabram@thebeaconjournal.com.

Robert Lockwood Jr. ...noted Mississippi Delta blues guitarist; 91

The Lowell Sun

Article Last Updated:11/23/2006 11:36:06 AM EST

CLEVELAND (AP) -- Robert Lockwood Jr., a pioneering Mississippi Delta blues guitarist and singer who

forged a career in Cleveland, has died. He was 91.

Lockwood died Tuesday of respiratory failure at University Hospitals Case Medical Center, said spokesman

George Stamatis. He had been a patient since suffering a stroke on Nov. 3.

Lockwood was born in Turkey Scratch, Ark. At 11, he started guitar lessons with legendary bluesman Robert

Johnson, who briefly moved in with Lockwood's mother.

"He never showed me nothing two times," Lockwood said in a 2005 interview with The (Cleveland) Plain

Dealer. "After I got the foundation of the way he played, everything was easy."

Lockwood worked on street corners and in bars and became a musical mentor to B.B. King, who listened to

Lockwood in the 1940s on the "King Biscuit Time" radio show.

Lockwood moved to Chicago in the 1950s and was a session player on records by Little Walter, Sunnyland

Slim, Roosevelt Sykes and other blues musicians.He branched out from the

Robert Lockwood Jr. Passes On

Nov. 22, 2006

By John Schoenberger

Blues legend Robert Lockwood Jr. passed away on Nov. 21. He had been hospitalized and in critical condition

since Nov. 3 from a blood vessel that had burst in his head. He was 91.

Robert Lockwood Jr. was born March 27, 1915 in Turkey Scratch, Ark.. Lockwood’s first recordings came in

1941, with Doc Clayton, on his famous "Bluebird Sessions" in Aurora, Ill.. During these sessions, he cut four

singles under his own name. These were the first incarnations of “Take A Little Walk with Me” and “Little Boy

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

7

Shared by: Richard Smith

Blue,” Lockwood staples 60 years later. Over the years he recorded for Chess, Rounder, Trix, Delmark, Telarc

and M.C. Records.

In the last 20 years, the world has recognized Lockwood’s contributions to the blues genre. In 1980 he received

his first of many W.C. Handy Awards and in 1989 he was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame. In 1995 he

received a National Heritage Fellowship

Award and in 1998 he was inducted into the Delta Blues Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Miss.

Robert Lockwood Jr. Timeline

March 27, 1915 -- Robert Lockwood Jr. is born in Turkey Scratch, Ark.

1926 -- He begins to learn guitar from his mother's boyfriend, Robert Johnson.

1930 -- The 15-year-old begins playing professionally, often with ``stepfather'' Johnson and others including

Sonny Boy Williamson II and guitarist Johnny Shines.

1941 -- He makes his recording debut with Doc Clayton and records four songs under his own name, including

concert staples Take a Little Walk with Me and Little Boy Blue. He also reteams with Williamson, becoming

part of his wildly popular live radio show. Aspiring guitarist Riley B. (aka B.B.) King is among the many rapt

listeners.

1950s -- Lockwood lives the life of an itinerant musician in hot spots such as Memphis, St. Louis and Chicago,

where he becomes a session man for Chess Records.

1960s -- Taking the advice of Williamson, Lockwood moves to Cleveland where he settles to raise his family,

working various jobs to make ends meet and playing area clubs.

1970s -- He records his debut solo album, Steady Rollin' Man, followed by five more, including Contrasts and

Does 12.

1980s -- Lockwood reteams with old friend Johnny Shines to record several albums. Already a local hero,

Lockwood begins to receive awards and accolades, including induction into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1989.

1990s -- The blues icon plays locally when not performing at music festivals around the world. After staying

out of the studio for much of the decade, he records “I Got to Find Me a Woman in 1998 [Robert Lockwood, Jr.

honored me by inviting me (Richard ‘Buddah’ Smith native Bassist of Philadelphia PA) as a side man on this CD

accompanied by guitarist Riley B. (BB) King.] garners him a Grammy nomination.

2000s – Lockwood earns Grammy nod for his 2000 album Delta Crossroads, continues to play locally and

internationally.

Source: www.robert-lockwood.com, www.allmusic.com

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

8

Shared by: Richard Smith

Robert Lockwood, Jr. in his own words

Dick Russ

Created: 11/22/2006 2:34:39 PM

Updated:11/22/2006 4:13:47 PM

Blues legend Robert Lockwood, Jr. shares his music and memories

with Dick Russ in March, 2002, on Lockwood's 87th birthday.

Robert Lockwood, Jr., gets comfortable on a couch in the living room of his home on Cleveland's east side, the

same Lawnview Avenue house he's been living in for decades.

He offers his guest a taste of genuine southern moonshine, just in from somewhere in Alabama. "That's good

stuff," the blues legend opines, and proceeds on to a few bars of "C.C. Rider."

"See, I started to play music when I was eight years old. I started playing guitar at 13, and the guy who taught

me is on that wall right over there, Robert Johnson."

Lockwood points across the room to a large poster of Johnson, his stepfather and first teacher. "He was way

ahead of his time, so when he taught me to play he put me way ahead of my time."

"He played harmony and melody all at the same time on the guitar." Robert Junior duplicates his teacher's skill.

"And that's hard to do."

At 87, the blues master is comfortable with his guest, who grew up only six blocks away. In fact they had the

same house number in this east side neighborhood.

"That's a fact!" Lockwood chuckles, "but you weren't much more than a kid when I came up here." The

musician had moved to Cleveland from Chicago in 1960. He was born in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas.

The tunes continue as the great guitarist starts to talk about his genuinely good health at 87. "I eat all the right

kind of foods. I try to do the right things for my body."

"You have to work at it. You have to take care of yourself." Lockwood boasts he does dozens of pushups and

knee-bends each day.

"Music had something to do with it, becuase if it don't be for music, I'd be square as a brick!"

Thoughts turn to his incredible career.

"Well, I taught B.B. King." A poster of his fellow blues legend also hangs on the living room wall. "He holds

me responsible for his career."

The music business has been good to Robert Lockwood, Jr., but he wishes he'd hit the big time a little earlier.

"You know if I had done 30 years ago what I have my mind on now, I'd be a millionaire. See, if I'd been with a

big company I'd be a millionaire."

He talks of a comeback, as if he'd been missing. Cleveland music fans have known and loved him for decades.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

9

Shared by: Richard Smith

"I can come back because I'm creative. I come back and made records. You can't stop me from coming back."

Setting down his 12 string on the ample coffee table in front of the couch, the man known mostly as Robert

Junior reminisces, and wonders if his guest wants another taste of moonshine.

"I got a street downtown. I got a day in the year here. I got a day in the year in Pittsburgh. Shoot, I mean these

people been so good to me it kind of scared me."

He hoped all the kindness was not because someone suspected he was close to the end. "I said, am I fixin' to

split, you know?"

The bluesman chuckles in that almost bawdy Lockwood laugh. "I don't think so!"

His guest shoots back, "I hope not!"

Robert Junior takes this as he takes everything, in perfect stride. "Oh, boy!" He leans forward, eyes the guitar,

and starts making plans for next three years.

Blues Pioneer Robert Lockwood Jr. Dies

November 22, 2006, 2:55 PM ET

Robert Lockwood Jr., a pioneering Mississippi Delta blues guitarist and singer, has died. He was 91. Lockwood

died yesterday (Nov. 21) of respiratory failure at University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland.

Hospital spokesman George Stamatis said Lockwood had been a patient since suffering a stroke on Nov. 3.

Lockwood was born in 1915 in Turkey Scratch, Ark. At age 11, he started guitar lessons with legendary

bluesman Robert Johnson, who briefly moved in with Lockwood's mother. "He never showed me nothing two

times," Lockwood said in a 2005 interview with the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Lockwood worked on street corners and in bars and became a musical mentor to B.B. King, who listened to

Lockwood in the 1940s on the "King Biscuit Time" radio show broadcast from Helena, Ark.

Lockwood moved to Chicago in the 1950s and was a session player on records by Little Walter, Sunnyland

Slim, Roosevelt Sykes and other blues musicians. He branched out from the Delta-style blues to jump blues,

jazz and funk, recording for great independent blues labels such as Delmark, Trix and Rounder. In 1960, he

moved to Cleveland, and played in blues clubs for decades.

As a solo performer, Lockwood earned Grammy nominations for two albums: 1998's "I Got To Find Me a

Woman" and 2000's "Delta Crossroads."

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

10

Shared by: Richard Smith

Robert Lockwood, Jr. - One of the last surviving roots bluesman of

the twentieth century.

Robert Lockwood Jr. was born March 27, 1915 in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, a farming hamlet about 25 miles

west of Helena. 1915 was remarkable because several other monumental blues artists were born within a 100mile radius that year; notably Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Little Walter Jacobs, Memphis Slim, Johnny

Shines, and Honeyboy Edwards. They would all meet up in the future.

His first musical lessons were on the family pump organ. He learned the guitar, at age eleven, from Robert

Johnson, the mysterious delta bluesman, who was living with his mother. From Johnson, Lockwood learned

chords, timing, and stage presence. By the age of fifteen, Robert was playing professionally, often with

Johnson; sometimes with Johnny Shines or Rice Miller, who would soon be calling himself Sonny Boy

Williamson II. They would play fish fries, juke joints, and street corners. Once Johnson played one side of the

Sunflower River, while Lockwood manned the other bank. The people of Clarksville, Mississippi were milling

around the bridge; they couldn’t tell which guitarist was Robert Johnson. Young Lockwood had learned

Johnson’s techniques very well.

Johnson’s fast lifestyle caught up with him, passing away in 1937. Lockwood was 22 but prepared for the

future.

Lockwood’s first recordings came in 1941, with Doc Clayton, on his famous Bluebird Sessions in Aurora,

Illinois. During these sessions, he cut four singles under his own name. These were the first incarnations of

“Take A Little Walk with Me”, and “Little Boy Blue,” Lockwood staples sixty years later.

Later in 1941, Lockwood was back in Arkansas where he re-united with Sonny Boy II to host a live radio

program broadcast at noon from KFFA in Helena, sponsored by the King Biscuit Flower Company. James

“Peck” Curtis and Dudlow Taylor provided the rhythm. This show became a cultural phenomenon; everybody

would listen during his or her lunch hour. Several generations of southern bluesman can trace their musical

roots to the show.

Lockwood moved around, the usual route was Memphis, St. Louis, to Chicago. By the early 1950’s, he had

surfaced in the Windy City, where he became the top session man for Chess Records, the epitome of blues

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

11

Shared by: Richard Smith

labels. Sonny Boy Williamson II, Little Walter, Roosevelt Sykes, Sunnyland Slim, and Eddie Boyd, whom he

toured with for six years, you can hear his smooth chords on their recordings.

Blues was giving way to Rock and Roll, even in Chicago, so Lockwood moved to Cleveland, Ohio at the urging

of his old pal, Sonny Boy. Settling down and raising a family took priorities but blues was still in his soul, just

on the back burner.

In the late 1960s Lockwood would gig all around Cleveland, playing whenever he got the chance. Longforgotten clubs like Pirates Cove and Brothers Lounge were places where Lockwood taught his blues to

generations of local musicians and fans.

Lockwood’s solo recording career, exclusive of the 1941 Bluebird Sessions, began in 1970 with Delmark’s

Steady Rollin’ Man, backed by old friends Louis Myers, his brother Dave Myers, and Fred Below, collectively

known as The Aces. In 1972, Lockwood hooked up with famed musicologist, Pete Lowry to record Contrasts,

the first of two for Trix Records. Does 12 followed in 1975. They have been remastered and repackaged by Fuel

2000 Records.

In the early 1980s Lockwood teamed up with another long-time friend, Johnny Shines, to record three albums

for Rounder, which has been comprised into 1999’s Just the Blues. Plays Robert and Robert, a Black and Blue

recording of a solo show in Paris in 1982, was re-issued on Evidence in 1993.

From the early 1980s to 1996, there were no domestic Lockwood releases. In 1998, I’ve Got to Find Myself a

Woman was released by Verve, gaining a Grammy nomination. This was followed by Telarc’s Delta

Crossroads, also a Grammy contender in 2000. In 2001, What’s the Score was re-issued on Lockwood Records

which has the rights to his Japanese live recordings, previously only available on Peavine. They will be a future

project.

In the last twenty years, the Blues world has recognized Lockwood’s contributions to the genre. Recently,

Lockwood has amassed so many that it is not possible to list all of them. The most notable are:

1980 Lockwood receives the very first W.C. Handy Award for “best traditional blues album”

1989 Inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame

1995 Received National Heritage Fellowship Award, presented by Hilary Clinton

1996 Cleveland Mayor, Michael White, proclaims February 3, as “Robert Lockwood Day”

1997 Has street named “Robert Lockwood, Jr. Way” in Cleveland’s Flat District

1998 Inducted into Delta Blues Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Mississippi

2001 Received Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters from Case Western Reserve in Cleveland

2001 Received W.C. Handy for “best traditional blues album,” Delta Crossroads

2001 City of Pittsburgh named 8/18 “Robert Lockwood, Jr. Day”

2002 Received honorary Degree of "Doctor of Music" from Cleveland State University on 5/12

Not content to rest on his laurels, Lockwood is touring more than ever at age 86. Lockwood leads an eight-piece

band every Wednesday at Fat Fish Blue in Cleveland, roams the world playing his jazz-tinted Delta Blues, and

records once a year. Lockwood is in better mental and physical shape than many men years younger. His guitar

playing is as crisp as ever. Like a fine French cognac, he is only getting better with age; no dust, rust or must

here.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

12

Shared by: Richard Smith

(Dr. Lockwood Continued)

As Dr. Lockwood's career evolved, he became one of the most sought after and revered guitarists in the

business. Unlike Johnson whose playing style was kept a mystery, Dr. Lockwood became the esteemed

professor for a select group of emerging understudies such as B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Freddie King, Jimmy

Rogers, Matt "Guitar" Murphy and others. He was the guitar player's guitar player. Now put this into the

context of the impact he had on Rock-N-Roll and think of all the rock and rollers that refer to this list of

Robert's protégé's as influences. Artists such as Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Joe Walsh, all Rock-Roll

Hall of Fame inductees were either directly or indirectly influenced by Dr. Lockwood. Of course, it doesn't stop

with these artists.

He explained that Johnson only showed him something once and you'd better learn it. In the case of B.B., Dr.

Lockwood would show him twice. If he didn't get it after that, he would slap him on the back of the hand like a

teacher with a ruler to reinforce the lesson plan. As history has shown, B.B. turned out alright.

At 91 years of age, Dr. Lockwood practiced everyday and encouraged others to do the same. He was very

insistent with developing musicians about continuous improvement, about learning other styles of music, of the

importance of having a teacher, and of being totally committed to the art form. He once spent three hours with a

young student sharing stories, coaching him, explaining "that guitar is going to be your woman from now on.

You're going to have to sleep with it [to be good at it]. And you need to get yourself a teacher!" Every time

since then, when he saw Lockwood, Lockwood would ask "do you have a teacher yet? Did you hear what I

said?!"

Dr. Lockwood set a high bar for his student constituency. He showed respect for other musicians. When he

performed with others, he would always ask the audience "would you do me favor? Would you please give

everyone you have heard up here today a big round of applause." He was always well dressed. As a performer

he was very adamant about the importance of appearance and was very critical of performers who dressed

down. He once asked Mick Jagger "with all that money you have, can't you afford to buy some decent clothes?"

He also believed in the importance of educating younger audiences so in 2004 and again in 2006, Dr. Lockwood

participated in blues education programs hosted by The Blue Shoe Project who recently released a recording of

the 2004 event and plans a DVD release later next year. He was joined by his long-time friends Henry

Townsend, Pinetop Perkins and Honeyboy Edwards. The four elders gave "storyteller" performances, sharing

their lives, their wisdom and their music with 1300 students in Fort Worth, Texas. Once again Dr. Lockwood

was the Professor, holding class for the new generation of blues believers, confirming his place in blues history

at the head of the class. The 2004 and 2006 events are possibly two of Dr. Lockwood's last live recordings.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

13

Shared by: Richard Smith

Dr. Lockwood's contributions to American music and blues in particular earned him two doctoral degrees,

making his Doctorate title official. He also received the National Endowment for the Arts Heritage Fellowship

Award, the highest honor our country bestows on performers in the traditional arts, a crowning achievement

reserved for a very short list of American performing artists. He received numerous W.C. Handy (now Blues

Music) awards, several Grammy nominations, was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame and the Delta Blues

Hall of Fame, has a street in Cleveland named after him, two Robert Lockwood, Jr. "days", one in Cleveland

and another in Pittsburgh, and too many other awards to mention.

In later years, Dr. Lockwood played a blue custom 12-string electric, one of only two ever made with a

resonance that was heavenly. As anyone will tell you, his style was impossible to copy let alone master.

Watching him play was a marvel of modern musicianship. Although his prowess as a band leader and composer

was extraordinary, his solo compositions on 12-string are arguably the best examples of the spirituality, the

complexity, the beauty and the genius that is undeniably Dr. Robert Lockwood, Jr.

His sometimes challenging demeanor was often misinterpreted. Most people would agree that he never mixed

words or beat around the bush. If he had something to say, he would lay it out there and you always knew where

you stood. And many times his volleys were followed by laughter proving his bark was much worse than his

bite.

The other side of Dr. Lockwood was one of the nurturer, the teacher, the professor; sharing of his wisdom, softspoken, kind, sincere and one of the most generous people you could ever meet. He would give you the shirt off

his back if you needed it and expected nothing in return. But you better need it!

Dr. Lockwood's secret of Longevity? He discovered early on that the secret to life was doing what you love to

do and he was passionate about music and everything about it. He loved learning music, teaching music and

playing music. He was a health nut long before it was popular. He worked out nearly every day. When he had

heart problems, he created an inversion plank that allowed him to invert himself regularly to take the pressure

off his heart. His problem went away. He was also a naturalist when it came to food. He purchased his meat and

poultry from the Amish for years, free of hormones and other unhealthy additives. He once told his long-time

friend Henry Townsend he needed to do the same and to get off the "dope meat."

Although drugs and the entertainment business seem to be synonymous, Dr. Lockwood had no interest in them.

His only vices were his music, fried catfish, and a little Hennessey now and then.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

14

Shared by: Richard Smith

Dr. Lockwood was the consummate teacher passing on to others what Robert Johnson had given to him;

teaching; about music, about appearance, about commitment, about friendship and about how to live your life –

the one and only "Professor of the blues."

View photos of Dr. Lockwood at the National Bikers Roundup, 8/20/06

Robert Lockwood Jr: 1915-2006

Another Blues Legend Passes into History

Saying goodbye to such an influential artist as Robert Lockwood, Jr., especially over the

Thanksgiving holidays, is never easy.

And yet, when considering how deep his musical genius intertwines throughout history, one

can't help but be thankful. His talent, voice, and charisma fashioned a vital cornerstone in

American culture. Lockwood wasn’t just a guitar player. He was an architect.

Born in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas on March 27, 1915, Lockwood’s first exposure to performing

came while playing the pump organ at his father’s church. At age 11, he was introduced to the

guitar by famed bluesman Robert Johnson, who came to live with Lockwood’s mother after his

parents divorced.

Robert Johnson (whose blues origins were steeped in mystery) taught Lockwood everything

from chords to timing to stage presence. It was no easy task, especially since Johnson never

taught his apprentice/stepson the same method more than twice. But, by age 15, he had

mastered his stepfather’s technique. So well, in fact, that during a riverside show in Clarksville,

Mississippi, fans could hardly tell the two guitarists apart.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

15

Shared by: Richard Smith

After signing with Bluebird Records in 1941, Robert Lockwood, Jr. embarked on a prolific

recording career that spanned almost 7 decades. That same year, he and fellow bluesman Sonny

Boy Williamson II gained widespread recognition by performing on the historic KFFA, during

a program known as "King Biscuit Time." The cultural impact of the show was far-reaching,

inspiring countless southern blues musicians including Lockwood’s protege, B.B. King.

From 1944 to 1949, Lockwood toured the Midwest extensively, playing at venues in St. Louis,

Memphis, and Chicago. By the early 1950’s, he had become the signature recording artist for

Chess Records, the most prominent of blues record labels in the Windy City.

As rock and roll progressively dominated the music scene, Lockwood focused his energies

exclusively on the blues. During the late 1960s and 1970s, Robert aggressively recorded on

various labels, collaborating with Muddy Waters, Pete Lowry, and the Aces. Giving highprofile performances in almost-forgotten clubs around Cleveland, Lockwood shared his talents

with fellow blues players and fans.

Such was Robert Lockwood, Jr.’s dedication to the genre that, unsurprisingly, his achievements

garnered national recognition. Over the next 20 years, he received countless awards for his

contributions to blues and roots music. In 1980, Lockwood was handed the first ever W.C.

Handy Award for best blues album (three more were soon to follow). He was inducted into the

Blues Hall of Fame 1989, and in 1995, he received the National Heritage Fellowship Award

from then-First Lady Hillary Clinton. Not content to rest on his laurels, Lockwood earned an

honorary doctorate in 2001 from Case Western Reserve in Cleveland, and a second from

Cleveland State University the following year.

But what justified Robert Lockwood, Jr. weren’t his lofty accolades. It came down to one word:

character. Despite a seemingly gruff demeanor, he exuded an uncanny level of generosity

towards his fellow man. For Lockwood, every statement of instruction or motivation always

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

16

Shared by: Richard Smith

had an action to back it up. His philosophy was a simple one, not unlike that of a samurai

warrior: success comes only through practice and personal dedication.

In his final years of his life, Robert found the perfect medium to demonstrate that philosophy.

Thanks to The Blue Shoe Project, a non-profit organization promoting awareness of blues in

education, Lockwood became involved in a series of performances and educational programs

geared towards students. Most notably, he was featured alongside fellow blues contemporaries

David "Honeyboy" Edwards, Joe Willie "Pinetop" Perkins, and the late Henry James Townsend

in The Last of the Great Mississippi Delta Bluesmen showcase earlier this year.

As an artist, performer, mentor, and family man, Robert Lockwood, Jr. truly experienced life

from all angles. His integrity, backed by nearly a century of unmatched skill, is what musicians,

fans, and now students, will remember for generations to come.

A Conversation with Robert Lockwood, Jr.

When I met Robert Lockwood, Jr. in June of 2000 he invited me to his home for an interview

for the Rock & Roll Library. Lockwood, now eighty years old, is a Grammy nominated blues

guitarist, one of the most famous Chicago sidemen of the fifties, and is the step-son of blues

legend Robert Johnson.

We want people to understand why you continue to play and why you continue to tour and how

important the music is in your life. Can you kind of speak to that?

RL: Well, in the beginning I started playing at eight. It's about all I ever learned really. I started

playing professionally at fifteen and I played by myself about ten years then I got a band. I been

playing all my life, and then the next thing, while I was real young, Robert Johnson come up to

my mothers house.

How old were you when you met Robert Johnson?

RL: I was thirteen.

Did he give you your first guitar?

RL: No, no, no. No, me and him together made a guitar.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

17

Shared by: Richard Smith

How did that sound?

RL: It didn't stay together long. My auntie bought my first guitar she's still living. She's only

four years older than I am. Well, anyway, Robert was a recording artist and he was way ahead

of his own time so, by him teaching me put me ahead of my own time.

What did people think about him at that time? When he was so far ahead of his own time? What

do you remember about that time?

RL: When you're ahead of your own time people don't know that you're ahead of your time. See

that's what really happened, they found out he's ahead of his time after he had done so much.

There wasn't anyone else doing it and that's when they said he was rare. You understand? By

him teaching me, put me way ahead of my own time. I started playing the piano then I switched

from the piano to the guitar. So I had a little experience with what the music was about and to

learn from him was easy because I was already playing. That's what my mother and him they

didn't understand that. But I learned fast, real fast

So he saw that you were good, that you picked it up very quickly.

RL: Yeah, then I was real good, real fast.

What type of ways did he influence your guitar style?

RL: Well, it wasn't nothing special to see. Everybody, all the guitar players, there was always

two of them. Robert was playing his own music, his own melody and backing himself up. So

that was easy to see. So I just said, well that's what I want to do. I got his picture there on the

wall. You ever seen it?

I have only seen two pictures of him.

RL: Two different pictures. One of him sitting crossed legged holding his guitar and this

picture, he's standing up with a guitar in his hand.

Did you have a good relationship? Were you friendly when you played?

RL: Well, yes, if we hadn't been, he'd never taught me. He didn't want to teach nobody.

Johnny Shine?

RL: He didn't teach nobody else. No damn body else. Nobody.

So that was a really unique experience for you.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

18

Shared by: Richard Smith

RL: Yes, and Johnny Shine to me was, well, we grew up pretty close together. I never went

nowhere with him but to Mississippi I went one place to play with Johnny in Arkansas.

Did you play with Robert Johnson a lot?

RL: No

Very rarely?

RL: Very rarely

A few occasions though? Once, in Mississippi you said?

RL: We were together twice in Mississippi and once in Arkansas. That's it.

How old were you when you played those gigs?

RL: How old was I? Fifteen, sixteen.

What was the climate of the places you were playing?

RL: There was no places.

You were playing at parties or in juke joints. And what about when you were finally able to get

into recording studios?

RL: When I made my first record from RCA

Was it Blackbird?

RL: In 1940.

Was that in Chicago?

RL: Yes and during that time it was in wartime so the material they made records out of was

very short. There was a hell of a shortage of that. So I started recording at the wrong time, didn't

get the right paper in the wrong time. So I couldn't I probably could've gotten another recording

session but I didn't really try. Well, our problem was they found me being so good, so young,

that I listened to all the other guys who were making records and there just was no comparison.

When I came up there to record the guy who was working for RCA Victor tried to brainwash

me and said I don't know whether your stuff's gonna sell or not. At that time it wasn't paying

nothing but fifty dollars and they were using four sides then for a recording session. Two

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

19

Shared by: Richard Smith

records, and they would pay you fifty dollars for that, twelve fifty a side. I wouldn't record for

that.

That's when you went down to King Biscuit?

RL: Yes. So I wouldn't record for the twelve dollars fifty cents a side. Dr. Clayton and I were

together and Dr. Clayton being a little older than I was had a little better knowledge about what

was happening. He was a better-educated young fella anyway. So I got a thousand dollars for

doing my playing and recording with him.

That's a little better.

RL: That's a lot better. So after we done the recording session, I left Chicago and went back to

St. Louis. And I had to get a social security card before I could get paid. So I got the social

security card, came back to Chicago and picked up my money. And left there again and I went

back in 1940. I went back in 1941 and I stayed in Chicago until 1960. I worked for Chess,

Checker, Otto, RCA Victor. I worked out of all those studios. I worked as a studio musician for

about twelve years.

You got to play with a lot of different people then?

RL: That's the way I learned to play everything. Jazz and everything else.

Did you have a favorite person who came in to record?

RL: Well it wasn't that way, we was working for the company.

So you had to play with everybody?

RL: Whenever somebody was getting ready to record, we were up on the kind of things they

had done.

Were there people that you preferred to play with? Your friends?

RL: Normally we didn't hardly get a chance to know nobody. After you record for them then

you know them. When you're working out of a studio you don't have choices. So, whoever

come in there, whatever they done that fits their category, that's what you do.

And so much later in the 80's you started your own label?

RL: Oh, I only started my own label here lately. Since I been here. I had the label oh about ten

or eleven years. I started my own label because I got sick of people tryin to twist me into other

people's image. That's what they do. And if you don't like it you can't record. So I fixed that and

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

20

Shared by: Richard Smith

got my own damn label so I could do what I want to do when I get ready. Ever since I have the

label people been steady wanting to hire me. They don't want us to have our own label. You

know they don't. They don't want the musicians today to have their own labels either. B.B. King

got his own already, Ray Charles got his, Stevie Wonder got his. They don't get time to record

on them.

RL: I got a manager and that's my son, and he usually charges for interviews, and we don't do

them for nothing so you're lucky.

I am honored you are talking with us today.

RL: I was responsible for B.B.'s career, Elsa Tucker and several other guys who I worked at. I

worked with Walter, I worked with Otis Span, I worked with Muddy Waters. I worked with the

Moonglows. If they didn't understand what was happening I had to teach them. So that's the

way they got taught. I never went out just to be no teacher. I played with B.B. about a year. His

timing was so damn bad he couldn't understand nothing I was trying to tell him. So his sponsor

wanted me to play a bass with him. He didn't know how to play nothing. He couldn't play lead

either. But his sponsor didn't know no more than he did you know, so I told his sponsor I, I

couldn't stop playing the guitar to play the bass and I told him what to do for him. B.B. didn't

know where that come from either. I told him to put him with a band and he'd have to find out

where he was going cause you can't work with no band unless you know something. So, B.B.

been listening to the bass ever since. He's listening to the bass right now. Now he can read. He

can read and play now. Yeah.

You have had a fantastic career there have been so many highlights; how was the Grammy

nomination in 1999?

RL: Well, there's so much about this business that you don't know about. I would have been in

the Grammy's damn near all my life but I never was handled by no big company. People don't

know. I been with the small company's it don't do you no good. You know, and, I guess it was

because I was eligible to lead everybody else's band, so I didn't really worry about it. I was

getting, there was decent pay. Didn't have to be no leader. I didn't have to be no really leader; I

was leading other people's bands. When I finally left Chicago I had to get my own band. When I

was in Chicago I didn't have to.

The blues embody so much about America and about the times and the way life was for so many

people

RL: Well, rhythm and entertainment seemingly, we was born with that. So the reason why blues

is so strong is Blues is history. And that'll never go. Plus, Blues was born in America it's really

the only American music. Blues and Jazz stuff that we recorded.

Who do you think is going to take blues into the next century? Are there any players out there

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

21

Shared by: Richard Smith

that you like?

RL: (Laughing) Blues ain't never gonna go no place because it's too valuable as a whole.

But it continues to evolve, do you think?

RL: Yeah, all music does that. But the blues can't, ain't never gonna be able to go because it's

the foundation. I mean it'll do things that it has done, so far. It went from uh, rhythm to changes,

chord changes and big band, jazz, blues, there's been steady changes, I seen it change about five

or six times. And it kind of repeats itself. The more people learn about music then the more

changes they can make in it. I guess that's the way it is.

Are there any players or any young players that you see out there doing this?

RL: No. Young players only copping what we done. Well, in so many words it's getting simpler

because the white society don't know what's happening with a lot of things, it takes ya'll a long

time. You know what I used to have to do? When my clientele got white, I had to stop looking

at you all dance. I'm serious, I'm very serious.

At this point we were laughing out loud but Robert kept saying that he was serious and his eyes

told me he was. I had to close my eyes and just not look because I was laughing so hard tears

were running down my face.

I'm sorry

RL: Ya'll just didn't have no damn rhythm.

Robert's eyes had softened as he saw how embarrassed I was by my counterparts not knowing

how to dance. Laughing as well,

RL: Ain't nothing to be sorry about. Ya'll just don't have it till you find out what it is

We appreciate the music and we try to move to it.

RL: My clientele has been white for about forty or fifty years and I'm noticing that ya'll been

learning how to dance.

Good, cause we try.

RL: People are coming together little by little.

Do you see that?

RL: Music is the article that's been damaged. I had a Hillbilly band coming on behind me when

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

22

Shared by: Richard Smith

I was in Little Rock, Arkansas. I worked on KLXR for I don't know, for a year. And it's

incredible the way musicians get along and the way ordinary square people get along. You just

don't know how pitiful it really is until you see it. That other band had six pieces, my band had

seven and we would join each other for each other's shows. And they were extraordinary good

and we were playing jazz and stuff and what caused us to get together was I was coming on

right in front of them. They was coming on right behind me. When I found out they was doing

this, the radio had needed a tube in my station wagon. I never got a chance to hear them.

So I guess I been on KLXR about four months later and my piano player put a tube in the radio.

The broadcast came on after. Let's listen to these goddamn Hillbillies. So I said ok and we

turned it on, like yesterday we had "One O'clock Jump" and stuff like that on the program. They

were taking everything we do and playing it tomorrow. That's what people do. When we turned

that radio on and somebody was doing "One O'clock Jump" it was Count Basie or somebody, a

damn string band! Laughing out loud, we all got out of the station wagon and went back inside

and the band leader fell on the floor. It was funny as hell. They were good musicians, very

good.

But they just couldn't play the "One O'clock Jump?"

RL: No, no. The person who was working in the station with them was involved in all different

stuff. After we got together, we was buying a half gallon of liquor everyday. There was thirteen

people so it was just enough to give everybody a little buzz. I guess we had been doing this

about a month I guess. So the little guy in the control room, he seen this. So he told me to come

up in his office. So I got ready to go up there, the other guy says I know this concerns the bands,

so he said I'm going too. I got up there and the guy starts saying he doesn't think it's very nice

that we are drinking together and all that. And the white boy hit the ceiling, we both did. When

we got through with his ass, he was drinking with us.

Big laugh from Robert.

So you had experiences where white musicians stood up for you.

RL: Nine times out of ten, musicians have not been prejudice. The square world is because they

don't know any better. Still don't know, and you're a hell of a victim because you don't know.

Congratulations to Robert Lockwood, Jr. who recently won a W.C. Handy Blues Award for

Best Acoustic Album 2000. Robert was also nominated for Traditional Male Artist of the Year.

His prior W.C. Handy Blues Awards include: 1999 - Traditional Male Artist of the Year and

1999 - Traditional Album of the Year.

Selected Discography:

Delta Crossroads 2000, Telarc

Robert Lockwood Jr. 2000, Black & Blue

Complete Trix Recordings 1999, Trix

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

23

Shared by: Richard Smith

I Got to Find Me a Woman 1998, Verve

What's The Score 1991, Evidence

Plays Robert and Robert 1982, Evidence

Mr. Blues Is Back to Stay 1980, Rounder

Hangin' On 1979, Rounder

Does 12 1977, Trix

Blues Live in Japan 1975, Advent

Contrasts 1974, Trix

Steady Rollin' Man 1970, Delmark

Robert Lockwood, Jr. plays every Wednesday at FATFISH BLUE at the corners of Prospect

and Ontario, Cleveland, OH and you can also see him every Friday at Club XO located at 8307

Madison Cleveland, Ohio 44102

Copyright 2000 Rock & Roll Library All Rights Reserved. This article may not be published in

whole or in part with out writtten authorization from the Rock & Roll Library.

Robert Lockwood, Jr. continued

24

Shared by: Richard Smith