Develop Program Schedule

advertisement

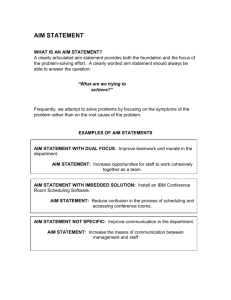

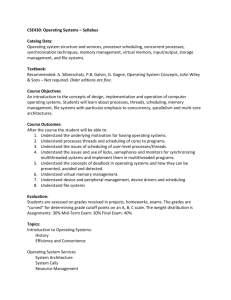

Air Force Life Cycle Management Center Standard Process To Develop Program Schedule Process Owner: AFLCMC/AZ Date: 9 Jan 2014 Version: 1.1 Record of Changes. Process numbering starts with 1.0. Minor changes are annotated by changing the second digit, i.e., the first minor change after the basic document would be recorded as “1.1”. Major changes are annotated by changing the first digit, i.e., the first major change after release of the basic document would be numbered as “2.0”. Version 1.0 1.1 Record of Changes Effective Date Summary 26 Nov 2013 Process standard approved by S&P Board on 7 Nov 2013. 9 Jan 2014 Added Predictive Scheduling Tool (PST) to pp 4,6, Appendix A p14 i ii Develop Program Schedule 1.0 Description. Scheduling is one of the basic requirements of program management planning and strategic analysis. The process to develop a program schedule includes the activities to plan schedule development, select a scheduling method and tool, develop the program schedule based on specific program data and requirements, baseline the schedule and then monitor, analyze, manage and report on schedule performance. 1.1 In order to realize the full value of the schedule, labor and non-labor resources must be assigned to the tasks. The government resource planning process includes the following activities: loading a program schedule with labor resources, assigning resources to program tasks, optimizing resource allocations, verifying the resulting schedule and establishing the schedule’s baseline, analyzing subsequent schedule impacts due to task completion progress, and an on-going assessment of resource assignments and optimization of resource allocations. 1.2 This standard process is mandatory for all programs that require a program schedule (ref. AFI 63-101) and may be used as a guide for discretionary program scheduling. Although aimed at acquisition programs, the process document contains universal scheduling fundamentals appropriate for other government and industry activities. 2.0 Purpose. The purpose of scheduling is to establish the time required for a program, to capture that time in a schedule baseline, and to provide insight into progress towards program completion by allowing comparison of actual accomplishments relative to that baseline. This baseline becomes the basis of the Acquisition Program Baseline (APB) defined by the program scope, and against which actual progress is determined. A wellbuilt, logically-linked, resource-loaded schedule will provide the critical path of activities required to accomplish required work as actual progress is measured. 3.0 Potential Entry/Exit Criteria and Inputs/Outputs 3.1 Entry Criteria. This process applies when: 3.1.1 A Program Executive Officer (PEO) or other authority directs a program/effort to have a government schedule. 3.2 Exit Criteria. This process no longer applies when: 3.2.1 Upon completion or disposal of the program/effort. 3.2.2 The PEO determines there is no further requirement for the schedule. 3.3 Inputs. PEO/HHQ direction, program requirements and data, contractor schedule 3.4 Outputs. Schedule Plan, Baseline Schedule, Schedule with actual data, critical path, driving path(s), schedule analysis and reports 1 4.0 Process Workflow and Activities. 4.1 Suppliers, Inputs, Process, Outputs, Customers (SIPOC), Table 1. Table 1. SIPOC Suppliers Inputs Process Outputs Customers PEO, PM, HHQ Direction Plan Scheduling Schedule plan, IMP PEO, PM, Program Office Program Office Program requirements and data, Schedule Plan, IMP Build Schedule Program schedule PEO, PM, Program Office Program Office Program schedule, program data Manage Schedule Program schedule, Predictive analysis HHQ, PEO, PM, Program Office 4.2 Process Flowchart. The process flowchart below, Figure 1, represents the process to develop a program schedule. The activities are further defined in Para 4.3 Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). 4.3 Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). The below WBS, Table 2, provides additional detail for the activity boxes in the above flowchart. The MS Excel version of this WBS with more detail is at Attachment 1. 4.4 Additional work tables, figures, or checklists. Additional instruction for developing program schedules is provided at Appendix A. 2 Figure 1. Develop Program Schedule Process Flowchart PEO AFLCMC Standard Process to Develop Program Schedule Approved? (APB, MS, etc.) Acq Strat, Program Info, Need for Program Schedule PEO provide direction Start No Program Office 1.1 Develop schedule plan 1-Set expectations 2-Plan resources 3-Determine tool 1.3.4 Programmatic Adjustment? Complete/Disposal Yes No Yes 1.2 Build program schedule 1-Describe deliverables Mechanically 2-Define tasks sound? Yes 3-Sequence tasks 4-Est. task durations 5-Assign resources No 6-Set milestones/constraints 1.2.3 7-Assess schedule Set Baseline End Normal Update Cycle Continue to manage & analyze schedule 1.3.3 Report schedule 1.3.2 Analyze schedule 1.3.1 Status Is it a major change in scope? Minor changes in scope No Yes Major changes in scope Other Input Critical/Key/Other Processes applicable to the program CP CP CP CP CP CP KP KP KP KP Status of Critical/Key/Other Processes OP OP CP CP CP CP CP CP KP KP KP KP OP OP 3 Table 2. WBS Lvl WBS Activity 1 1.0 Develop Program Schedule 2 1.1 Develop Schedule Plan (IMP) 3 1.1.1 Set Expectations 3 1.1.2 Plan Resources 3 1.1.3 Determine & Acquire Tool 2 1.2 3 1.2.1 Build 3 3 2 3 3 3 3 Build Program Schedule (IMS) Description The process is performed by PMs and their teams when the PEO, or other authority, directs a program to have a PMO schedule. PM must consider the mix of SMEs and where to get them, which scheduling tool is most appropriate, and the battle rhythm for statusing and reporting. Determine and communicate: Resource-loading or not, working calendar, status interval, reporting interval, & justifications for: duration estimates, hard constraints, nonFS relationships, Lead/Lag. Scheduling is a collaborative effort and requires input from many functional areas. It is up to the PM to ensure SMEs are identified, including a scheduling resource ("scheduler"). In most cases, MS Project will be sufficient. For programs with an EVM component or high levels of integration (i.e. multiple, integrated schedules), matching the Ktr tool may be warranted. PM develops and maintains the Integrated Master Plan (IMP) and Integrated Master Schedule (IMS). Both IMP and IMS integrate program activities to include disposal and schedules into a single sight picture. This includes IMSs from all contractors, as well as government activities to include test plans and depot activation. Describe Deliverables, Define Tasks, Sequence Tasks/Identify Touchpoints, Estimate Task Durations, Assign Resources, Set Milestones/Constraints. 1.2.2 Analyze SME technical assessment, Horizontal/Vertical Traceability, Float, Critical & Driving Path analysis, Baseline analysis, Schedule Health Assessment 1.2.3 Set Baseline Snapshot in time of the time-phased plan to accomplish the work. 1.3 Manage PM must use the information from the schedule and other Program sources to make programmatic adjustments. 1.3.1 Status Enter actual values as program progresses. Collect status and update schedule with “actual” start/finish dates. 1.3.2 Analyze SME technical assessment, Horizontal/Vertical Traceability, Schedule Float, CP/Driving Path analysis, Baseline analysis, SHA, Schedule Risk Assessment, Resource Leveling 1.3.3 Report Schedule Report schedule status, as required, via MAR, SMART, Status CCAR/eCCAR. For Services Acquisitions $100M and above, utilize the Predictive Scheduling Tool (PST). 1.3.4 Programmatic On-track (Baseline)? Do EVM data & schedule data support Adjustments each other? What has changed on CP? Does it matter? If so, what do we do? OPR PM Time 5-6 mo PM 60d PM PM 20d PM 60d PM,SMEs, 40d Scheduler PM, SMEs, 20d Scheduler SMEs 10d Scheduler PM 5d Scheduler PM 20d/ mo PM, SMEs, 5d Scheduler PM 10d PM 5d PM, SMEs, 5d Scheduler 4 5.0 Measurement. 5.1 Process Results. There is no requirement at the Center-level to collect or report specific process results such as timeline data for performing the Develop Program Schedule Process. However, metrics related to process results should be collected at the Program Office and/or PEO level as a normal way of reporting program performance. At the program level, performance is regularly reported through normal reporting systems such as SMART and CCAR/eCCAR. 5.2 Process Evaluation. AFLCMC/AQ shall utilize the AFLCMC Metrics Tracking tool or SOCCER annually to report the following information collected from PEOs or program offices: 5.2.1 By Acquisition Category (ACAT), including Services & non-ACAT: • Total # Pgms • # for which a Govt schedule is mandatory • # for which a Govt schedule is in place • # for which a Govt schedule is actually used • # for which resources are loaded in a Govt schedule • # for which Govt schedule is integrated with contractor schedule(s) • Govt schedule format - # PowerPoint, MS Project, OPP, P6, or Other 5.2.2 What problem do you want an AFLCMC process for schedules to solve? 6.0 Roles and Responsibilities. Schedule development is a collaborative effort. Involvement includes, but is not limited to, program managers, functional managers, subject matter experts (SME), and scheduling resources. 6.1 Program Manager 6.1.1 The PM is responsible for ensuring a pool of resources (e.g. Multi-Functional Team, MFT) is available to define, describe and evaluate schedule tasks. This pool should include functional SMEs from engineering (EN), finance (FM), contracting (PK), logistics (LG), acquisition (AQ), and others as required by the program scope. Directorate-level SMEs may be available on-loan for use by multiple programs. 6.1.2 The PM is responsible for ensuring that program resources are scheduled. 6.1.3 The PM is responsible for choosing and acquiring licenses for a scheduling tool (e.g. MS Project). 6.2 Functional managers are responsible for ensuring that the resources provided to the PM have the appropriate skills required to perform program tasks. 6.3 Subject Matter Experts (SME) 6.3.1 SMEs are responsible for identifying/reviewing the tasks needed to perform the work. 6.3.2 SMEs are responsible for identifying the skill level of the resources required to perform the work. 5 6.3.3 SMEs are responsible for providing status updates (i.e. Actual Start/Finish dates), as well as revision estimates for durations and resource skill-levels. 6.4 The scheduling resource (scheduler) is responsible for replicating SME & PM information in the scheduling tool. The scheduler is responsible for ensuring that generally accepted scheduling best practices are applied when building and maintaining the program schedule. 6.5 Other users, performers, suppliers, and/or decision makers of the process may provide information regarding development, status, and management of the schedule throughout the program’s life cycle. 7.0 Tools. 7.1 MS Project - automated scheduling tool (recommended) 7.2 DCMA 14PA macro - schedule health assessment tool (recommended) 7.3 Acquisition Document Development & Management (ADDM) system documentation process flow and templates (recommended) 7.4 SMART - AF-level System Management and Reporting Tool (mandatory) 7.5 wInsight - EVM presentation tool (optional) 7.6 Milestones Professional - schedule presentation tool (optional) 7.7 Comprehensive Cost and Requirement (CCAR) or Executive CCAR (eCCAR) – used to report schedule status 7.8 Predictive Scheduling Tool (PST) – AFMC/PK-owned MS Excel Workbook tool for standard quarterly reporting of Services Acquisitions (mandatory for Services Acquisitions of $100M and above) 8.0 Training. There are numerous training opportunities related to scheduling that are offered by AFLCMC/AZA (ACE), DAU, and AFIT as listed in Table 3 below. 6 Table 3. Training opportunities Course Title Schedule Development Basics - Knowledge Areas 14 Point Assessment Basics Knowledge Areas Schedule Development Basics - Hands-On Provider AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) 14 Point Assessment Basics Hands-On AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) Schedule Analysis Basics (Horizontal/vertical traceability, CP Analysis, Baseline Analysis) Government Resource Planning Schedule Risk Assessment Basics - Knowledge Areas Schedule Risk Assessment Basics - Hands-On Microsoft Project (Basic)* * - as training budget permits AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) Microsoft Project (Intermediate)* * - as training budget permits Introduction to Scheduling (CLM 012) Predictive Analysis & Scheduling (CLM 040) AF Fundamentals of Acquisition Management (FAM 103) Principals of Schedule Management (EVM 263) Program Managers Course (PMT 401) AFLCMC/AQPC (OmniCom*) AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) AFLCMC/AZA (WPAFB ACE) AFLCMC/AQPC (OmniCom*) Length Notes 2 hrs - Conf Rm or DCO - By Request 2 hrs - Conf Rm or DCO - By Request 1 day - Focus Week - Journeyman Training Wk - By Request ½ day - Focus Week - Journeyman Training Wk - By Request 1 hr - Conf Rm or DCO - By Request DAU - Conf Rm or DCO - By Request 2 hrs - Conf Rm or DCO - By Request ½ day - Conf Rm or DCO - By Request 1 day - Focus Week - Journeyman Training Wk 1 day - Focus Week - Journeyman Training Wk 1-2 hrs CBT DAU 1-2 hrs CBT AFIT 1 day DAU 3 days DAU 1 hr WPAFB In-Residence (Huntsville, AL) 10 wks DAU Kettering 7 9.0 Definitions, Guiding Principles and/or Ground Rules & Assumptions. 9.1 Guiding Principles or assumptions 9.1.1 The process for developing a government schedule should not to be confused with a contractor integrated master schedule (CIMS); however, both may be developed independently and integrated by the program office (electronically or through manual touchpoints) into a true, program master schedule. 9.1.2 This process assumes that a pool of labor resources (e.g. MFT) has been allocated to the Program Management Office (PMO) prior to loading the schedule with resources. 9.2 DEFINITION OF TERMS 14PA - DCMA 14 Point Assessment Baseline Task - a Total Task with a baseline finish date prior to or equal to the status date. Used in 14PA calculations for BEI (Complete Tasks/Baseline Tasks) Complete Task - a Total Task that has an Actual Finish Date. Used in 14PA calculations for BEI (Complete Tasks/Baseline Tasks) Critical Path - the longest path of logically related activities with the lowest total float representing the shortest amount of time in which the schedule can be completed Driving Path - the longest path of logically related activities with the lowest total float representing the shortest amount of time to a selected task/milestone. A driving path might or might not be on the critical path. Float/Slack - The amount of time that an activity/milestone can be delayed before impacting another task or project completion Free Float – the amount of time an activity/milestone can slip before impacting its immediate successor(s) Incomplete Task - a Total Task that does not have an Actual Finish date. Used in 14PA calculations Lag - a delay between tasks; a task with a positive number in the predecessor field (e.g. 21fs+2d) Lead - an overlap between tasks; a task with a negative number in the predecessor field (e.g. 21fs-2d) Milestone Task - a zero-duration task marking a significant event; milestone tasks should not have resources assigned Total Float – the amount of time an activity/milestone can slip before impacting the scheduled project completion date Total Task - DCMA term used to describe any task that is NOT: a Summary/Rollup task, or a Level of Effort task, or a zero-duration task (e.g. Milestone task). Used in 14PA calculations 8 9.3 ACRONYMS ACE - Acquisition Center of Excellence BEI - Baseline Execution Index DCMA - Defense Contract Management Agency EV - Earned Value EVM - Earned Value Management EVMS - Earned Value Management System FF - Finish-to-Finish FNLT - Finish No Later Than FS - Finish-to-Start GFE - Government Furnished Equipment GFI - Government Furnished Information IMP - Integrated Master Plan IMS - Integrated Master Schedule MAIS - Major Automated Information System MFO - Must Finish On MSO - Must Start On OTB - Over Target Baseline OTS - Over Target Schedule PM - Program Manager PMB - Performance Management Baseline PST - Predictive Scheduling Tool SF - Start-to-Finish SHA - Schedule Health Assessment SME - Subject Matter Expert (EN, FM, PK, LG, AQ, etc.) SNET - Start No Earlier Than SNLT - Start No Later Than SS - Start-to-Start WBS - Work Breakdown Structure 9 10.0 References to Law, Policy, Instructions or Guidance. 10.1 DoD 5000.02. This regulation sets forth mandatory procedures for Major Defense Acquisition Programs and Major Automated Information System acquisition programs. 10.2 MIL-STD-881C. This standard addresses mandatory procedures for those programs subject to DoD 5000.02. It offers uniformity in definition and consistency of approach for developing the top levels of the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). It does not, however, identify Level 3 elements for the program management WBS elements. This allows the program manager flexibility to identify efforts that are important to the specific program. A source the program manager can use to support decisions about which efforts to include is the Acquisition Document Development and Management (ADDM) system. The ADDM system provides templates of and a repository for all documents required by AFI 63-101 and typically produced by a program during its acquisition life cycle. 10.3 AFI 63-101, Acquisition and Sustainment Life Cycle Management. This instruction establishes Integrated Life Cycle Management guidelines, policies and procedures. It states, “The PM shall develop and maintain the Integrated Master Plan (IMP) and Integrated Master Schedule (IMS). Both IMP and IMS integrate all program activities to include disposal and schedules into a single sight picture. This includes integrated master schedules from all contractors, as well as government activities to include test plans and depot activation.” Chapter 2.6 of the instruction provides guidance to the Program Manager in understanding mandatory required documentation. 10.4 DID DI-MGMT-81861, Integrated Program Management Reporting (IPMR) Data Item Description. Contains format and content preparation instructions for the IMS. 10.5 IMP & IMS Preparation and Use Guide (DoD, v.0.9, 21 Oct 05). Provides guidance for the preparation and implementation of a program’s Integrated Master Plan (IMP) and Integrated Master Schedule (IMS). 10.6 GAO Schedule Assessment Guide (GAO-12-120G, May 2012). Best practices for project schedules. 10.7 PASEG, Planning & Scheduling Excellence Guide (NDIA PMSC, v 2.0, 22 Jun 12). Practical approaches for building, using, and maintaining an Integrated Master Schedule (IMS). Attachment 1. MS Excel WBS 10 Develop Program Schedule_WBS 11 12 Appendix A Supporting Detail for Developing a Program Schedule 1. Develop Program Schedule. The AFLCMC Develop Program Schedule process focuses on the minimum elements for developing a schedule to capture the government-side activities required to implement and manage a program. This can include the documentation activities required to progress to the next milestone, the tasks needed to acquire and deliver government furnished equipment (GFE), awarding contracts, fitting into the big picture, and many other activities the program office must accomplish to support the program. Basically, if something specific is being produced or built (even documentation), or to reach a specific goal (e.g. Milestone B approval), then a schedule should be developed in order to determine a realistic estimate of the time (duration) required to complete the effort with the resources available to the program office. While we often need our programs to fit within a certain timeframe or finish by a certain time, artificially compressing them in lieu of realism does little to accomplish the program goals. Service and sustainment efforts are particularly tricky and should be considered by the PEO or other authority on a case-by-case basis to determine whether a schedule is appropriate for the effort. Ex. 1 - Services Your program office supports an ACAT III IT system with semi-annual software releases to track depot maintenance costs. The PMO consist of a GS-14 PM and 8 A&AS contractors on a FFP services contract. The A&AS contract does not have a schedule as a CDRL deliverable because of the level of effort (LOE) nature of the support (e.g. PM expertise for 3 years). Does the PMO need a schedule? Yes. Although the effort of the contract support is LOE in nature, the overall program itself has specific deliverables (s/w releases), documentation (CCA, NDAA, C&A, PB/BES, etc.), and interactions (s/w developer, DISA, OLs, SAF, etc.) that need to occur. In order to maximize the PMO resources, a government-side schedule (aka PMO schedule) should be developed and managed. Ex. 2 - Sustainment Your program office performs depot maintenance on the KC-123. The PMO consist of a GS14 PM and 8 A&AS contractors on a FFP services contract. The A&AS contract does not have a schedule as a CDRL deliverable because of the level of effort (LOE) nature of the support (e.g. 8 A/C mechanics for 3 years). Does the PMO need a schedule? Yes. Although the effort of the contract support is LOE in nature, the overall program itself has specific deliverables (repaired A/C), documentation (parts requisition, MTBF/MTTR, etc.), and interaction with the platform PMO (TOs, maintenance schedules, etc.) that need to occur. In order to maximize the PMO resources, a government-side schedule should be developed and managed. 1.1. Develop Schedule Plan. Scheduling is not a 15 minute exercise, but an iterative process that requires up-front and periodic planning to capture the full scope of the government activities required to implement and manage the program. When a program begins to 1 consume government resources (man-hours, material, etc.), it is time to plan those activities in a schedule. WBS. Although MIL-STD-881C does not identify Level 3 elements for the program management WBS elements, that does not mean a government-side WBS is not required. Even if there are no government tasks associated with a program’s deliverables, there are most certainly government activities associated with budget requirements (cost), milestone reviews (schedule), technical justification (performance), and the documentation to support them. These activities require resources that must be coordinated and managed, and should be developed into a government WBS. The Acquisition Document Development and Management (ADDM) system can aide in developing the WBS. ADDM can also provide templates and associated timing for the documentation required for a program based on its stage in the acquisition life cycle. IMP. The WBS should be decomposed into the program IMP. “The IMP is an eventbased plan consisting of a hierarchy of program events, with each event being supported by specific accomplishments, and each accomplishment associated with specific criteria to be satisfied for its completion.” The IMP also provides a narrative explaining the overall management of the program. Schedule. The IMP should be decomposed into the government schedule by adding the specific task required to support satisfaction of the criteria identified in the IMP, and identifying the durations of those task and the relationships among them. By following the process below, the program office should be able to develop a manageable, executable government schedule. Cost Estimate. The Government Schedule drives many of the activities and milestones that determine the Fiscal Year Phasing of the Government cost estimate, which in turn becomes the Government’s budget. The cost analyst needs to be informed as the schedule develops to assure that the schedule is executable and to assure that the Government’s estimate and budget aligns with the schedule’s milestones. 1.1.1. Plan Resources. The PM is responsible for ensuring a pool of resources (e.g. MultiFunctional Team, MFT) is available to define, describe and evaluate schedule tasks. This pool should include functional SMEs from engineering (EN), finance (FM), contracting (PK), logistics (LG), acquisition (AQ), and others as required by the program scope. Directorate-level SMEs may be available on-loan for use by multiple programs. SMEs are responsible for identifying/ reviewing the tasks needed to perform the work. They are responsible for identifying the skill level of the resources required to perform the work, and for providing status updates (i.e. Actual Start/Finish dates), as well as revision estimates for durations, resource skill-levels, etc. 1.1.2. Determine/Acquire a Scheduling Tool. A scheduling tool is not part of the AF Standard Desktop suite of applications, therefore it may be necessary for the PM to choose and acquire enough licenses of a scheduling tool (e.g. MS Project) to support the program (1 license is often sufficient). In most cases, MS Project will be sufficient, but may still require purchase by the PMO. For programs with an EVM component or high levels of integration or risk (e.g. multiple, integrated schedules), matching the contractor’s tool may be warranted, and will require purchase. For small, simple, shortterm (<6 months), or low-risk programs, a scheduling tool may not be necessary at all and standard presentation and/or spreadsheet tools may be sufficient. 2 Another factor to consider when choosing a scheduling tool is whether the desired tool is on the AF COTS/GOTS EPL. There are 3 scheduling tools that are typically on the EPL: Microsoft Project, Deltek OPP, & Oracle Primavera (P6). Before purchasing a scheduling tool, verify that the specific version of the desired tool is listed on the EPL. If the tool is no longer listed on the EPL, or another tool is identified, it will be the PM’s responsibility to sponsor the tool through the EPL process. 1.1.3. Set Scheduling Expectations. Scheduling is a collaborative effort requiring participation of the PM, a number of subject matter experts from different areas of specialization, and a scheduling resource (scheduler). In order to effectively utilize a schedule to manage a program, it is important that each member of the PMO team know their responsibilities with regard to the schedule, and is committed to providing besteffort inputs. It is important for the PM to express these scheduling expectations early and often. Communicate the Battle Rhythm. The entire PMO should be aware of how often the schedule must be reported (e.g. MAR, PMR, etc.). Set the status/update interval. It is important to status/update the schedule on a regular basis. Best-practice is to update the schedule at least twice as often as it has to be reported. Bi-weekly and monthly are two common intervals. SME participation is required. It is important that SME’s are aware of their commitment to the schedule. SMEs are responsible for identifying/reviewing the tasks needed to perform the work. They are responsible for identifying the skill level of the resources required to perform the work, and for providing status updates (i.e. Actual Start/Finish dates), as well as revision estimates for durations, resource skill-levels, etc. A Scheduler is required (if a scheduling tool is used). An individual familiar with the chosen scheduling tool and learned in scheduling best practices will be an invaluable asset. Scheduling resources are few-and-far-between. It may be necessary to hire, develop, become, or share a scheduler. In addition to building and maintaining the schedule, the scheduler (with assistance from the SMEs) should perform baseline analysis, critical path analysis and driving path analysis. Schedule Analysis is required (if a scheduling tool is used). Schedule analysis should be performed on a monthly basis. At a minimum, the DCMA 14-point Schedule Health Assessment (SHA) should be performed. There is an EPLapproved macro from DCMA. There are also commercially-available products that perform the 14 point assessment on MS Project and other scheduling tools. Consider price and EPL considerations before purchasing a commercial assessment tool. In addition to the SHA, baseline analysis, critical path analysis and driving path analysis should be performed on a regular basis, as well as monthly technical assessments by the various SME. Resource Loading should be considered (if a scheduling tool is used). Resource loading can run the gamut from simply assigning POCs, to full-up resource loading with a resource pool, resource calendars, labor rates, etc. Determining the level of resource loading will itself be constrained by the resource(s) available to maintain a resource-loaded schedule. The POC-method requires little maintenance; building a 3 resource pool using skill code designations requires moderate maintenance; full-up resource loading can be a full-time position, especially on a large program. Working Calendar(s). A calendar must be defined within the scheduling tool that accurately represents the general working days available to the program. Holidays and across-the-board days off should not be considered working days. Justifications. Durations, hard constraints, non-FS relationships, and Lead/Lag are all acceptable scheduling techniques, provided each is adequately justified. Justifications for these items should be documented in the Acquisition Plan or other PMO documentation. 1.1.3.1. Rolling Wave Planning. Rolling wave planning is a technique in which detail planning is done in increments so that work is only planned out as far as practical. Six months is an acceptable increment, but should be based on the program. If the increment is too long, there are too many unknowns to have confidence in the schedule. If the increment is too short, the planning activity never ends. Keep in mind that a task in one wave may become a summary task in a future wave. Make sure the logic (predecessors, successors, constraints, etc.) and resources are transferred from the original task to its detail tasks (i.e. No logic or resources on summary tasks). If the schedule has been baselined, the new detail tasks must fit in the same timeframe as the original task (i.e. the sum of the new task durations must equal the original task duration). There are two types of rolling wave planning: traditional and block. See figures on the next two pages. 4 Traditional Rolling Wave Planning. Work is planned out as far as possible for each work package or control account. The planning process is continual, with detail plans being established ahead of start dates. Detail Planned Work Planning Package(s) Detail Planned Work Planning Package(s) Detail Planned Work Planning Package(s) Future Work – Planning Packages Program Start Completion “Block” Rolling Wave Planning. Work is planned out as far as practical in total. Done in “waves”, where all work is detailed to a given point (usually a critical decision point in the program). This planning process is also continual, with detail plans being established ahead of start dates. Wave 1 Begin planning next wave Planning Package(s) Detail Planned Work Prog Start Prelim Des Review Post PDR Program Completion Wave 2 Begin planning next wave Planning Package(s) Detail Planned Work Post PDR Critical Des Review Post CDR Program Completion 5 Rolling Wave Example: Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 End IBR 3 mo 3 mo 3 mo 3 mo Detail Plan (1st 6 mo) Planning Pkg (2nd 6 mo) 1 Event 3 Event 1.1 SA-1 3.1 SA-1 1.1.1 AC-1 3.1.1 AC-1 1.1.1.1 Task1 3.1.2 AC-2 1.1.2 AC-2 3.2 SA-2 1.1.2.1 Task1 3.2.1 AC-1 1.2 SA-2 3.2.2 AC-2 1.2.1 AC-1 4 Event 1.2.1.1 Task1 4.1 SA-1 1.2.1.2 Task2 4.1.1 AC-1 1.2.1.2.1 TaskA 4.1.2 AC-2 1.2.1.2.2 TaskB 4.2 SA-2 1.2.2 AC-2 4.2.1 AC-1 1.2.2.1 Task1 4.2.2 AC-2 1.2.2.2 Task2 2 Event 2.1 SA-1 2.1.1 AC-1 2.1.1.1 Task1 2.1.2 AC-2 2.1.2.1 Task1 2.2 SA-2 2.2.1 AC-1 2.2.1.1 Task1 2.2.1.2 Task2 2.2.2 AC-2 2.2.2.1 Task1 2.2.2.2 Task2 Start planning the next wave at this point 6 mo Planning Pkg 5 Event 5.1 SA-1 5.2 SA-2 6 Event 6.1 SA-1 6.2 SA-2 6 mo Planning Pkg 7 Event 7.1 SA-1 7.2 SA-2 8 Event 8.1 SA-1 8.2 SA-2 12 mo Planning Pkg 9 Event 10 Event 12 mo Planning Pkg 11 Event 12 Event 12 mo Planning Pkg 13 Event 14 Event Program End So that when you get to here… Status Date (Approx today) Tasks In work (First Wave) 3 months later… 6 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 End IBR 3 mo 3 mo 3 mo 3 mo Detail Plan (1st 6 mo) Detail Plan (2nd 6 mo) 1 Event 3 Event 1.1 SA-1 3.1 SA-1 1.1.1 AC-1 3.1.1 AC-1 1.1.1.1 Task1 3.1.1.1 Task1 1.1.2 AC-2 3.1.1.2 Task2 1.1.2.1 Task1 3.1.2 AC-2 1.2 SA-2 3.1.2.1 Task1 1.2.1 AC-1 3.2 SA-2 1.2.1.1 Task1 3.2.1 AC-1 1.2.1.2 Task2 3.2.1.1 Task1 1.2.1.2.1 TaskA 3.2.2 AC-2 1.2.1.2.2 TaskB 3.2.2.1 Task1 1.2.2 AC-2 4 Event 1.2.2.1 Task1 4.1 SA-1 1.2.2.2 Task2 4.1.1 AC-1 2 Event 4.1.1.1 Task1 2.1 SA-1 4.1.2 AC-2 2.1.1 AC-1 4.1.2.1 Task1 2.1.1.1 Task1 4.1.2.2 Task2 2.1.2 AC-2 4.2 SA-2 2.1.2.1 Task1 4.2.1 AC-1 2.2 SA-2 4.2.1.1 Task1 2.2.1 AC-1 4.2.2 AC-2 2.2.1.1 Task1 4.2.2.1 Task1 2.2.1.2 Task2 2.2.2 AC-2 Tasks In work 2.2.2.1 Task1 (Next Wave) 2.2.2.2 Task2 Tasks complete 6 mo Planning Pkg 5 Event 5.1 SA-1 5.2 SA-2 6 Event 6.1 SA-1 6.2 SA-2 6 mo 12 mo Planning Pkg 7 Event 7.1 SA-1 7.2 SA-2 8 Event 8.1 SA-1 8.2 SA-2 Planning Pkg 9 Event 9.1 SA-1 9.2 SA-2 10 Event 10.1 SA-1 Start planning the next wave at this point …the next wave is detail planned 12 mo Planning Pkg 11 Event 12 Event 12 mo Planning Pkg 13 Event 14 Event Program End So that when you get to here, the next wave is detail planned Status Date (Approx today) 1.2. Build Program Schedule. This section provides guidance for developing a Government schedule. 1.2.1. Build. Describe deliverables, define tasks, sequence tasks and identify touchpoints, estimate durations, assign resources, and set constraints. 1.2.1.1. Deliverable descriptions. The scheduler is responsible for transposing the items from the IMP to the Government schedule. Descriptions should be nouns. For example, if the deliverable is a risk management plan, one might describe it as “Risk Management Plan.” Once complete, the list of deliverables in the scheduling tool must map to the IMP on a one-for-one basis. 1.2.1.2. Task definition. SMEs (from EN, FM, PK, LG, AQ, etc.) are responsible for defining all tasks required to produce the deliverables listed in the IMP. The scheduling resource (aka scheduler) is responsible for documenting the task definitions, as well as naming the tasks. [NOTE: The schedule is not a “to-do” list. For example, defining tasks to make phone calls is not appropriate for inclusion in a program schedule list of tasks.] 1.2.1.3. Task descriptions. The scheduler is responsible for naming the tasks. Tasks must be uniquely described, including a verb and at least one object, with clarifying adjectives. For example, if the task being described is the effort to produce the first draft of a document, one might describe it as “Write First Draft-Risk Management Plan.” 7 1.2.1.4. Task sequencing. SMEs (from EN, FM, PK, LG, AQ, etc.) are responsible for defining the sequence in which the tasks will be performed. The scheduler is responsible for documenting the sequence in the scheduling tool. Task sequencing provides the logic that drives the schedule, and allows the scheduling tool to perform its calculations. For example, if Task A is required to be complete prior to the start of Task B, then the scheduler will key a finish-to-start relationship between A & B into the scheduling tool. Every discreet (not summary) task must have at least one predecessor and one successor, with the exception of: the program’s start milestone will have successors only; the finish milestone will have predecessors only. 8 Types of task-to-task relationships: Finish to Start (FS) Task X Task Y Finish to Finish (FF) Task X Task Y Start to Start Task X (SS) Task Y Start to Finish Task X (SF) Task Y Task sequencing is one of the key factors in building a useful schedule. With the exceptions of the first task (i.e. start milestone) and last task (i.e. finish milestone), every discrete task (NOT summary tasks) should have at least one predecessor and one successor. For tasks using other than a Finish-to-Start (FS) relationship, additional predecessors and/or successors are required to “complete” the logic. EX: In a finish-to-finish (FF) relationship, the second task must have an additional predecessor, or else nothing drives the start of the second task. In a start-to-start (SS) relationship, the first task must have an additional successor, or else the first task never has to finish. In a start-to-finish (SF) relationship, the first task must have an additional successor (or else the first task never has to finish), and the second task must have an additional predecessor (or else nothing drives the start of the second task). Touchpoints. Touchpoints represent giver-receiver handoffs between schedules. If scheduling tools and the electronic environment are compatible, electronic touchpoints 9 can be used to identify the giver-receiver handoffs, and are assigned as predecessors/successors. If electronic touchpoints cannot be used, manual touchpoints can be created. A manual touchpoint will take the form of an inserted “receiver” task or milestone in each affected schedule that represents the handoff (or “giver” task(s)) from another schedule. A manual touchpoint as a task will represent the work being accomplished in one schedule (a single or multiple tasks) as a single task whose duration equals the duration of the task(s) it represents in the “giver” schedule. By assigning predecessors/successors to the touchpoint task in the “receiver” schedule, you can determine the impact to the “receiver” schedule based on the status of the task(s) in the “giver” schedule. By monitoring the start/finish date, duration, and logic in the “giver” schedule, you can determine the impact to the “receiver” schedule and make adjustments to the “receiver” schedule to reflect the current plan from month to month. A manual touchpoint as a milestone will represent the delivery of an item from the “giver” schedule. By assigning predecessors/successors to the touchpoint milestone in the “receiver” schedule, you can determine the impact to the “receiver” schedule based on the status of the task(s) in the “giver” schedule. By monitoring the start/finish date, and logic in the “giver” schedule, you can determine the impact to the “receiver” schedule and make adjustments (e.g. predecessors/successors, duration) to the “receiver” schedule to reflect the current plan from month to month. 1.2.1.5. Estimating task duration. SMEs (from EN, FM, PK, LG, AQ, etc.) are responsible for estimating the duration of tasks. The scheduler is responsible for documenting the estimates in the scheduling tool. Tasks should be scoped so that the duration will be less than two times the update cycle (i.e., status interval). Ideally, duration values should not be more than three times the update cycle. Specifically, for tasks other than milestone (i.e., zero-duration) tasks, duration values should range from 5 to 44 days (1 week to ~2 months). Under certain circumstances, such as critical decision activities, tasks can have a duration value of less than 5 days, but never less than 1 day. Duration value units should be days, not hours. [NOTE: “To-do” list types of tasks are usually too small in duration to be included in a program task list.] 1.2.1.6. Resource assignments. The PM is responsible for ensuring a pool of resources (e.g. Multi-Functional Team, MFT) is available to define, describe and evaluate schedule tasks. This pool should include functional SMEs from engineering (EN), finance (FM), contracting (PK), logistics (LG), acquisition (AQ), and others as required by the program scope. Directorate-level SMEs may be available on-loan for use by multiple programs. The SMEs are responsible for identifying the skills required to perform program tasks. The scheduler is responsible for creating a representative resource pool, and assigning resources to tasks based on SME recommendations. 1.2.1.6.1. Load labor resources and associated capacity in the scheduling tool. Resource names can come from sources such as MS Outlook, a list of labor categories, or can be manually keyed in the schedule file. Capacity is the amount of a unit of resource that is available to be consumed by the program. These quantities will be determined when the pool of labor resources is allocated to the PMO. Should a resource have a 10 work calendar with exceptions (ex., the resource does not work on Friday of each week), then a calendar indicating the exception is loaded at this time. 1.2.1.6.2. Assign resources and required level of effort to tasks. Assigning resources entails selecting a name from the resource list in the scheduling tool and adding it to the task record. The level of effort required of a resource to perform the task is entered when the resource is assigned to the task, and is expressed in a percentage of a unit. For example, if a resource is required to perform a task on a full-time basis, then the required level of effort is 100%. 1.2.1.6.3. Perform resource leveling and optimize resources. Resource leveling entails “smoothing” a resource’s allocation contour. A resource’s allocation can vary from time-period to time-period. For instance, a resource could be under-allocated during a given time period and over-allocated during another. This variation, or contour, needs to be adjusted in such a way that the allocation matches the resource’s availability. Scheduling software enables this leveling. Using software to level resource allocations could require adjusting task precedence, task duration, and/or the required level of effort. During the leveling process, the software will schedule the work in accordance with the resource’s calendar. Leveling should be performed prior to setting the original baseline, as well as during the life of the program as task completion occurs. Concurrent with resource leveling, resource usage should be optimized. This means streamlining resource deployment given constraints such as skill level, task objective, and time. Optimization should be performed prior to setting the original baseline, as well as during the life of the program as task completion occurs. If true resource loading is determined to be non-value-added by the PM/PEO, the PM should consider assigning responsible POCs at the task level using an open/unused freetext field (e.g. “Text10”) within the scheduling tool. While earned value and resource leveling cannot be accomplished using this method, it allows the PM to assign and track work informally. 1.2.1.7. Set Milestones. A milestone is a zero-duration task. The scheduler is responsible for keying at least two milestones into the scheduling tool. One is the program’s start event; the other is the program’s finish event. Additional milestones, such as PDR, CDR, etc., should also be added to the program schedule. 1.2.1.8. Constraint dates. A constraint is a limitation or restraint placed on a task or milestone that affects the start and finish dates of the task or milestone. The PM is responsible for specifying constraints. The scheduler is responsible for keying the constraint dates in the scheduling tool. Constraint dates must be used judiciously, as they corrupt the logic defined by sequencing, durations, and relationship types. Constraints must NOT be used to replace schedule logic. The preferred way to “hold a date” in a schedule is by using a soft constraint (SNET/FNET). This allows you to hold a date until the logic (i.e. its predecessor(s)) “pushes against” that date, in which case the constrained task will slip one-for-one with its predecessor task(s). Hard constraints should NOT be used to hold a date. The 11 primary purpose for a hard constraint (MSO/MFO, SNLT/FNLT) is to perform what-if analyses on an existing schedule to determine the impact on the program if a specific task must start or finish earlier than predicted by the early start/finish calculated by the scheduling tool. The types of constraints are: 1.2.2. Analyze. Verification analysis entails getting confirmation from Subject Matter Experts (SME) that the technical content is accurate, and assessing the mechanical soundness of the schedule (called “Schedule Health Assessment (SHA)”). The SMEs must confirm that all of the technical work is scheduled, the required resources are assigned to all tasks, that effort estimates exist for all tasks, and the tasks are logically sequenced. An SHA must be performed to identify mechanical issues that must be resolved. Technical and health assessments should be performed prior to setting the original baseline, as well as periodically during the life of the program. The scheduler is responsible for conducting technical schedule quality reviews with the SMEs. The reviews occur once the scheduler has received all input from the SMEs and keyed it in the scheduling tool. The tool will calculate a time-phased plan of tasks. It is critical that the SMEs agree that the plan calculated by the tool reflects the real timing and technical nature of the planned work. The scheduler is also responsible for conducting schedule health assessments (SHA), which indicate the level of mechanical soundness of the schedule. The Post-Award Team (PAT) office in the Acquisition Center of Excellence (AFLCMC/AZAD) recommends using the DCMA 14 Point SHA Tool at a minimum to conduct the assessments. PAT can provide SHA implementation and assessment training. 1.2.3. Set Baseline. A baseline is the benchmark against which program performance will be measured. Project scheduling software enables the user to save task start and finish dates, 12 task duration values, and estimated effort as baseline start and finish dates, baseline duration values, and baseline effort. Prior to setting the schedule baseline, however, it is critical that the PM approve the schedule. The PM will base the approval on the results of the technical, health, and risk assessments performed on the schedule. Once the PM is confident that the schedule is mechanically sound, that the schedule includes all technical effort, and that risk handling plans have been documented, the PM will grant approval to set the baseline. The scheduler is responsible for setting the baseline using the scheduling tool. 1.3. Manage Program Schedule. As real-world status is input into the scheduling tool, variances will impact the tasks and resources. Resources will need to be re-allocated on a regular basis in order to continue to accomplish the required work. By analyzing schedule variances, the program manager can more accurately determine where resources are needed to accomplish the work. 1.3.1. Status. Before variances can be identified and subsequently evaluated, task completion status must be entered. Status data can be comprised of actual start and finish dates or actual effort, revised planned start and finish dates, revised effort estimates, and/or revised duration values. Status data will impact dates and duration of in-progress tasks, as well as future tasks. Best-practice is to update the schedule at least twice as often as it has to be reported. Bi-weekly and monthly are two common intervals. 1.3.2. Analyze 1.3.2.1. Verification. Verification entails getting confirmation from Subject Matter Experts (SME) that the technical content is accurate, assessing the mechanical soundness of the schedule (called “Schedule Health Assessment (SHA)”), and assessing schedule risks (called “Schedule Risk Assessment (SRA)”). The SMEs must confirm that all of the technical work is scheduled, the required resources are assigned to all tasks, that effort estimates exist for all tasks, and the tasks are logically sequenced. An SHA must be performed to identify mechanical issues that must be resolved. Once a schedule is technically and mechanically sound, an SRA could be performed to identify risk areas for which risk handling plans must be documented. Technical, health, and risk assessments should be performed prior to setting the original baseline, as well as periodically during the life of the program. The scheduler is responsible for conducting technical schedule quality reviews with the SMEs. The reviews occur once the scheduler has received all input from the SMEs and keyed it in the scheduling tool. The tool will calculate a time-phased plan of tasks. It is critical that the SMEs agree that the plan calculated by the tool reflects the real timing and technical nature of the planned work. The scheduler is also responsible for conducting schedule health assessments (SHA), which indicate the level of mechanical soundness of the schedule. The Post-Award Team (PAT) office in the Acquisition Center of Excellence (AFLCMC/AZAD) recommends using the DCMA 14 Point SHA Tool at a minimum to conduct the assessments. PAT can provide SHA implementation and assessment training. 13 The PM is responsible for ensuring that schedule risk assessments (SRA) are conducted. SRAs can quantify the likelihood that a given task will finish on the date calculated by the scheduling tool. The Post-Award Team office can provide SRA implementation and assessment training. 1.3.2.2. Analyze schedule variances. Before variances can be identified and subsequently evaluated, task completion status must be entered. Status data can be comprised of actual start and finish dates or actual effort, revised planned start and finish dates, revised effort estimates, and/or revised duration values. Status data will impact dates and duration of in-progress tasks, as well as future tasks. Status data that reveals actual start and finish dates, and/or actual effort data that vary from the baseline start and finish dates, and/or baseline effort, indicate that a variance exists. Evaluating the variance entails quantifying it. The size of the variance can be discerned from the task completion status. For example, a task that is started on schedule (i.e., the task actually started on the baseline start date) and is completed ahead of schedule (i.e., prior to the baseline finish date) indicates an ahead-of-schedule position. In this case, a favorable variance has occurred. The size of the variance is determined by comparing the number of days required to complete the task to the baseline duration value. For instance, if a resource finishes a task one day ahead of schedule, then the amount of the favorable variance is one. Conversely, a task that is started on schedule and is completed behind schedule (i.e., after the baseline finish date) indicates a behind-schedule position. In this case, an unfavorable variance has occurred. The number of days in excess of the task’s baseline duration that elapse before the task is finished is the amount of the variance. For instance, if the baseline duration of a task is 5 days and 6 days are required to perform the task, then the amount of the unfavorable variance is one day. 1.3.2.3. Adjust resource assignments and allocations. Revising assignments and allocations requires understanding the impact of a variance on a resource’s capacity. From a resource planning perspective, a favorable variance means that a resource has the capacity to start performing a succeeding task to which it is assigned ahead of schedule, assist a different resource working on a different task, or work on a different program altogether . The decision as to how to best consume the resource’s excess capacity lies with the PM. If the decision is to start working on a succeeding task ahead of schedule, then schedule revisions are not necessary. If the decision is to use the resource with excess capacity to assist a different resource working on a different task, then revisions to the resource’s task assignments is required. This change is temporary to the extent of the amount of excess capacity. If the decision is to move the resource with excess capacity to a different program, then revisions to the resource’s task assignments on each program is required. This change is temporary to the extent of the amount of excess capacity. In the case of an unfavorable variance, schedule delays and conflict among resources are likely. The effects of a schedule delay are manifold: (1) the resource that finished a task behind schedule cannot start succeeding tasks to which it is assigned on schedule; (2) other resources are delayed in their attempt to start dependent tasks on schedule; (3) the PM is presented with the challenge of making-up the lost time in order to achieve an onschedule close of the program if the delay occurs on the critical path. The PM has 14 several options from which to choose to resolve the behind-schedule issue and resource conflicts: (1) assign a resource(s) with excess capacity to the task(s) that are impacted by the delay; (2) re-plan the resources assigned to future tasks; (3) assign resource(s) with excess capacity on other program(s) to the program experiencing the delay; (4) increase the capacity of the resource pool. Executing each of these options will require some type of adjustment to the schedule using the scheduling software. 1.3.3. Report Schedule Status. PMs should communicate the status of the program as compared to the program schedule baseline. This includes tasks/ activities that completed early, on-schedule, and late. Furthermore, it is important for the PM to understand and communicate the impact of task completion (or failure to complete) on the program plan, and should articulate impact in terms of resource and duration adjustments. PMs should be able to discuss the critical path of activities to program completion, or the driving path to any milestone. For Services acquisitions of $100M and above, use PST for quarterly reporting required by AFPEO/CM. Predictive Scheduling Tool (PST) is the AFMC/PK owned MS Excel Workbook with embedded codes that is used for standard quarterly reporting of Services acquisition $100M and above. PST files are posted on the AFLCMC Strategic Services Portfolio Management SharePoint at: https://org.eis.afmc.af.mil/sites/ASCAQ/azs/Predictive%20Scheduling/Forms/AllItems.as px 1.3.4. Programmatic Adjustments. Is the program on-track (Baseline)? Do EVM data & schedule data support each other? What has changed on CP? Does it matter? If so, what do we do? Based on the variances identified during analysis, the PM will need to determine which issues can be affected by the program office, which issues are worthy of the limited PMO resources, and those issues beyond the PM’s control. Issues beyond the PM’s control should be elevated in order to obtain assistance or direction from the PEO or other authority. Additionally, while minor programmatic adjustments are within the program manager’s scope/power/jurisdiction/responsibility, major programmatic adjustments (directed rescoping, OTB/OTS, Nunn-McCurdy violation, critical or significant changes for MAIS Programs, etc.) must be reported up the chain of command, potentially all the way to Congress, for accountability and redirection. While major programmatic adjustments can occur with any program, those with realistic schedules have a much better chance of avoiding them than schedules that have been artificially compressed in order to meet a date or timeline. Summary of WBS 1.2 Build Program Schedule. Describe Deliverables Set Milestones Describe Tasks Define Tasks Trace Forward & Backward Set Constraints Sequence Tasks Conduct SME Verification Estimate Durations Assign Resources Set Baseline Manage Program 15 16