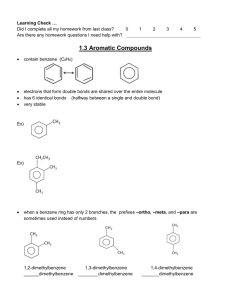

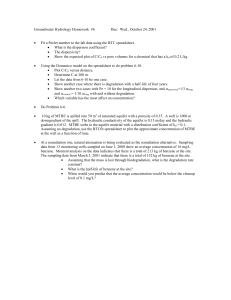

Benzene in Perrier Bottles

advertisement