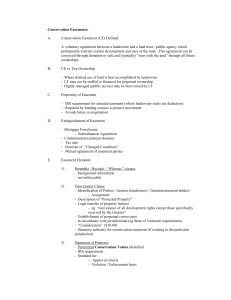

Virginia's Property II Outline

advertisement