THE

advertisement

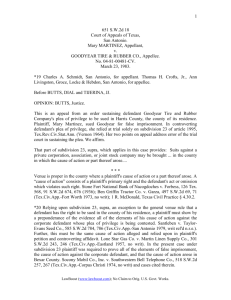

TITLE OPINION Bi, Terry E. Hogwood 'Curing title opinions, as the subject for a concise article, is far too broad a topic to give each aspect of the actions taken by landmen or attorneys ✓to present oil and gas clients with a "cured" title opinion. The author chose rrr on the underpinnings of the title curative process: • The Original Title Opinion Risk decisions made by the client company as well as the examining attorney and abstractor preparatory to and during the Ming of the original title opinion. • The Supplemental Title Opinion - Types of curative materials that will -sab " a title requirement as well as the risk decisions made by the client comshould one or more title requirements not be satisfied. • Two Nonwaivable Title Requirements Securing a copy of the patent from the General Land Office and obtaining an affidavit of use and occupancy. • Affidavits - Why, at the heart of curing a title requirement, affidavits do not amount to a marketable title. • Trespass To Try Title _ . T. ,771 C r ZC?.U The ultimate title curative action. 23 Landman J. FRED HAMBRIGHT, CPL THE ORIGINAL TITLE OPINION Kansas' only Aggie Landman Definition AAPL WAPL Oil & Gas Lease Acquisitions KANSAS • NEBRASKA • COLORADO 125 N. Market #1415 Wichita, Kansas 67202 CURED TITLE OPINION (316) 265-8541 EXPERIENCE T INTEGRITY, TECHNOLOGY An original title opinion is a legal document, usually addressing fee simple ownership (it may be limited to surface or mineral estate depending on the wishes of the client) of a given tract of land, which can only be prepared by a duly licensed attorney. An original title opinion is the first title opinion rendered for a given tract of land. It can be written for drilling or division order purposes. It is an interrelated document usually consisting of five distinct parts: • Property description Professional Energy Land Services f JJ �' IrL, '.),J �"JS emu! mJJ i d r�r11l1Ji!JjJJ '� 1 and ) j j iitf ve our clients time and money by mmwur custom programming to speed MMUMse checks, mineral histories, and ions, nationwide. JJIu:,s ur 'ur Worh up with , JImjjll;l �D1JIiJ7_1i l liE PJs i ' jJat riJ�1J f J r�Jill' hai T 33' a�;�§.3428�Toll'�Y 8$&233 �� www.bradI ybroussard.cottit 24 ) °`€ • Documents examined • Certification date of abstract/opinion • Ownership schedule • Comments and requirements The significant interrelationship of an original title opinion is between the ownership schedule and the list of comments and requirements. The ownership schedule may not be relied on until all of the title requirements have been deemed satisfied by the examining attorney. Stated differently, the examining attorney will not (and cannot) declare that marketable title to the fee simple interest has been achieved if even one outstanding title requirement remains. The author has never seen a 100 percent cured title opinion except for offshore tracts (state and federal) and some Indian tribal lands. Meaning? The majority of title opinions rendered for the oil and gas industry require that the oil companies rely on less than marketable title for drilling and royalty payment purposes (defensible title). That a title is not a marketable title is not in and of itself a problem. Almost all titles have one or more facts outside of the record that must be relied on to support the ownership schedule (heirship affidavit, adverse possession, etc.). The purpose of the original title opinion is to provide assurance to the client company that the mineral estate is properly leased and that no outstanding mineral interests in third parties remain unleased or leased to another company. Every time a title requirement is waived by a client company there is an increased risk that title to some or all of the mineral estate may fail. November / December 2011 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION A title opinion (either original or supplemental) rendered for a client is owned by the client, not the rendering attorney. The right to rely on the contents and conclusions of the title opinion belongs to the original client and to whomever else the rendering attorney (with the client's permission) will allow to utilize same. Stated another way, possession of a title opinion will not entitle the possessor of same to rely on its statement of ownership (backed by the malpractice insurance of the rendering attorney) unless the rendering attorney has granted his or her permission to the possessory CONTEX ENERGY CO DIGITAL SERVICES Wasted time traveling to the busy courthouse? No place to stay? Let us build your own courthouse database. Work at the convenience ofyour own office. Bobbi Kukla Digital Mgr. party to use and rely on same. PRELIMINARY DECISIONS 701-225-5507 (Office) 701-260-1477 (Cell) MADE BY CLIENTS Client companies face numerous decisions that, in the end, become initial risk decisions and form the framework for the original title opinion. The client company must first choose, prior to initiaring the title examination process: (1)Between using a title abstractor from a local title company, an attorney or a Landman to prepare the run sheets from which the examining attorney will examine the identified documents and prepare the original title opinion. The author's preference has always been to use Indmen for run sheet preparation. Abstractors typically focus only on surface titles in their primary employment capacity at a title company. More importantly, mineral titles are based on many different documents never encountered in a surface ownership search. Attorneys are not usually as familiar with courthouses and their records as are landmen and/or abstractors. Landmen possess full-time knowledge both of the courthouses (and their records location) as well as title chain preparation. (2) What records to use, i.e., only abstract plant records, only courthouse records or a combination of both. In the author's opinion, the best run sheet preparation process is to utilize the records of both '. 'rember i December 2011 THEOPHILUS OIL, GAS & LAND SERVICES, LLC Specializing in the Louisiana State Mineral Program with over 30 years of experience • State Mineral Lease Abstracting • State Mineral Lease Consulting • Mineral Lease Nominations & Bids • Mineral Leases • Assignments • BETH CANNON ' • State Ownership SONRIS System Landman =z • State Lease Sale Representation • Office of Conservation Research 263 Third Street, Suite 312 • Baton Rouge, LA 70801 Phone (225) 383-9301 • Fax (225) 383-9380 Email: theoogl@bellsouth.net I beththeoogl@bellsouth.net PAT THEOPHILUS Owner/President DLS DA VIS LAND SER VICES COMPLETE ENERGY LAND SERVICES Oil, Gas, Land & Mineral Leasing Lease Start-Up and GIS Database Set-Up Mapping and Complete GIS Data Services Shale, Crude, Pipeline. Transmission & Wind Projects Abstracting / Title Research & Ownership Reporting Due Diligence for Mineral & Surface Ownership ROW, Easement. Urban & Rural Projects NEPA Documentation and Field Work Environmental Due Diligence Environmental Compliance Research & Reporting THROUGHOUT THE U.S.A. FORT WORTH, TEXAS 817.332.4100 817.879.0104 bob.davis(�davislandservices.com 25 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION the abstract plant and courthouse. Practically speaking, where time is of the essence, initially building the chain of title in an abstract plant and then confirming same via the indices found in the county courthouse is the usual examination process employed by many abstractors. Many times documents are misindexed or not indexed at all in the courthouse. By starting the run sheet preparation process in the abstract plant, many if not all of such instruments may be located early on in the run sheet preparation process, thus saving considerable time and effort later in the courthouse portion of the examination process. A geographically based filing system (where each survey has all documents associated with that survey summarized in the abstract plant records) will usually catch most improperly filed documents. (Example: When searching "Branch Springs" in the Harris County Computer Index Records, the author found that the creative data inputrers could spell "Branch Springs" as one word or two words, abbreviate "Spring" to "SP," abbreviate "Branch" to "BR" and thereafter combine all permutations into numerous "spellings." The only sure way to catch all documents is to use the records of an abstract plant coupled with the indices in the county records.) From a risk standpoint, the only official records for lands located in a specific county are those found in the county clerk's office. If a document affecting title to a tract of land is filed in the office of the county clerk, there is constructive notice of its existence and the facts exhibited therein. (Miles v. Martin, 321 S. W. 2d. 62 (Tex 1959).) This rule of construction is limited to those instruments in a grantee's chain of title. (Ford v. ExxonMobil Chemical Co., 235 S. W. 3d. 615 (Tex 2007), including all recitals, references and reservations contained in or fairly disclosed by any instrument forming an essential link in the grantee's chain of title (Westland Oil Development Corp. v. Gulf Oil Corp., 637 S. W. 2d. 903 (Tex 1982).) What public records are to be reviewed - i.e., only the deed/official 26 records of the pertinent county and/or district court records and/or tax records. The fewer records reviewed, the greater the increased risk of missing a pertinent document. What comprises the totality of "public records" in a county courthouse is a subject for another paper. Attached as Exhibit "A" is a checklist of many of the potential public documents and indexes that may reside in a Texas county courthouse. The abstractor should always check with the county clerk to be sure that he or she knows where all indexes are so they can be examined in the process of building the title chain. Perhaps the most stunning example of nonindexed documents, at one time on file with the Harris County clerk, is the old set of books of early Title problems cannot be analyzed, cured or waived without an understanding of the title standard utilized by the examining attorney in the rendering of the original title opinion and/or supplemental title opinion. In Texas, fee simple title opinions - and specifically the underlying title requirements found in such opinions are written so that satisfaction of all title requirements will yield a "fee simple marketable title" for the tract of land under examination. Marketable title has been a defined legal term in Texas jurisprudence since the 1920s. (Lund v. Emerson, 204 S. W. 2d. 639 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1947, no writ hist.); Owens v. Jackson, 35 S. W. 2d. 186 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1931, writ dism'd w.o.j.); Texas Auto Co. v. Arbetter, 1 judgments affecting title to real property S. W. 2d. 334 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1927, in Harris County. These books (more than 100) resided in what was once known as the "Teapot Room" and sat behind the counter. The author personally examined some 20 of the hooks and found that they appeared to hold judgments rendered in Harris County (for an indeterminate period of time) affecting title to Harris County real property. Those judgments did not appear to be indexed in the Deed Records Index nor resident in the Deed Record books. No judgment affecting title to real property is binding on third parties until it is properly filed of record in the pertinent county deed records. (Woodward v. Ortiz, writ dism'd w.o.j.); Austin v. Carter, 296 237 S. W. 2d. 286 (Tex 1951).) More significantly, those judgment books have been moved to an undisclosed location. Are the judgments still binding on third parties even though the books cannot be located presently or are "stored" for historical purposes' Yes, the judgments are binding on all third parties even if they cannot presently be located. The disclaimer attached to any run sheet by an abstractor or landman must be carefully read and understood. Many times, in addition to limiting the amount of money (usually limited to the cost of the run sheet), a disclaimer will virtually take away all of the abstractor or landman's liability for any missed document for any reason, thus transferring all risk to the client company for any such failure in the examination process. S. W. 649 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1927, writ dism'd); and Ailing v. Vander Stucken, 194 S. W. 443 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1917, writ ref'd).) A "marketable title" is a title based solely on instruments of conveyance properly filed of record and is defined as that title which is reasonably free from such doubt that a prudent man, with knowledge of all of the salient facts and circumstances surrounding the title and their legal significance, would be willing to accept. An objection (read title requirement) to a marketable title is based on serious and reasonable doubts by the title examiner concerning the title that would induce a prudent man to hesitate in accepting a title affected by them. (Lund v. Emerson, 204 S. W. 2d. 639 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1947, no writ hist.); Owens v. Jackson, 35 S. W. 2d. 186 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1931, writ dism'd w.o.j.); Texas Auto Co. v. Arbetter, 1 S. W. 2d. 334 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1927, writ dism'd w.o.j.); Austin v. Carter, 296 S. W. 649 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1927, writ dism'd); and Ailing v. Vander Stucken, 194 S. W. 443 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1917, writ ref'd).)" (A Realistic Approach to Identifying and Curing Ancient Title Problems, Terry E. Hogwood 18th Advanced Oil, Gas and Mineral Law Course.) A title is not marketable if: (1) there is a reasonable chance that a third party could raise an issue concerning the validity of the title to the estate against November / December 2011 Landinan CURED TITLE OPINION Exhibit "A" INDEXES LOCATED IN THE COUNTY CLERK'S OFFICE If Discontinued, Name of Index Deed No. Volumes Dates in Use Reverse Index Records Deed of Trust Contracts Map Records Abstract of Judgment Federal Lien Attachment Lis pendens U CC M & M Liens Marriage Records Assumed Name Oil and Gas Records Probate Records Powers of Attorney Patents Town & Subdiv. Plats Cemetery Plats Death Certificates Official Records `.em ber /December 2011 27 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION the apparent owner (for instance, a claim of adverse possession), or (2) parol evidence is necessary to remove any doubt as to the validity and/or sufficiency of the owner's title (for instance, an affidavit of heirship to reflect a deceased's owners heirs-at-law) or (3) title rests upon a presumption of fact which, in the event of a suit contesting title, would probably become an issue of fact to be decided by a jury (for instance, whether additions to a tract of land occurred by accretion or avulsion) or (4) the record discloses outstanding interests in other parties that could reasonably subject the owner to litigation or compel such owner to resort to parol evidence to defend the title against the outstanding claims (for instance, a fee simple title with an outstanding, unreleased oil and gas lease is not a marketable title). (Lund v. Emerson, 204 S. W. 2d. 639 (Tex. Civ. App. 1947, no writ hist.); Owens v. Jackson, 35 S. W. 2d. 186 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1931, writ dism'd w.o.j.); Texas Auto Co. v. Arbetter, 1 S. W. 2d. 334 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1927, writ dism'd w.o.j.); Austin v. Carter, 296 S. W. 649 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1927, writ dism'd); and Ailing v. Vander Stucken, 194 S. W. 443 (Tex. Civ. App. 1917, writ ref'd).) All title opinions in Texas should be written in accordance with this legal standard. (A Realistic Approach to Identifying and Curing Ancient Title Problems, Terry E. Hopwood 18th Advanced Oil, Gas and Mineral Law Course.) As stated above, most onshore titles that are approved for drilling are approved on the basis of defensible title, not marketable title. A defensible title is one where the client, with advice and consultation from the title attorney, decides to waive the satisfaction of one or more title requirement(s) or to accept less than absolute proof that an outstanding title requirement has been satisfied. The client usually decides that, if sued on the waived title issue, it can win in a subsequent court case, i.e., a defensible title. The call of marketable title is to point out those title defects that, in the opinion of the title attorney, are such that a prudent man, with knowledge of all of the salient facts and circumstances surrounding the title and their legal significance, would not be willing to accept. Each title examiner, and indeed, each client oil company, develops a risk tolerance level depending on the expertise of the title attorney and the relative cost of the well and value of the anticipated reserves. The author was trained to note every title defect in the title opinion that impacted or could impact marketable title. If there was a title defect, it had to he pointed out. Thereafter, management, in consultation with the examining attorney, could decide which title requirements it felt comfortable in waiving and which it would attempt to cure. Other examining attorneys make a preliminary risk assessment of a potential title defect and oftentimes elect to waive same either with or without a title cornment. For instance, the typical title TotaLsiuLcom THE LANDMAN'S VIRTUAL OFFICE GIS Maps Abstract AssemblerTM Reports Executable Documents Secure, real-time and easy to use! 26 November /December 2011 Landinan CURED TITLE OPINION comment is as follows: "I note several early breaks in the chain of title to Examined Lands. Due to their early appearance in the chain of title, there appears to be little risk that any title claim could be made today as a result of said title breaks. However, in an abundance of caution, you should secure an affidavit of adverse possession for ......... " Often, the last sentence is omitted and the early title defects are merely noted as an advisory comment of their existence with no curative action prescribed to resolve the breaks. If an advisory comment only is made (which is much preferred by most clients), the examining attorney has accepted all of the attendant risk should one of the early breaks in the chain of title later assert itself (usually if production is established) via a claim to production as an unleased cotenant. Equally important is the issue of which party is the examiner attempting to confirm title in, i.e., the first fee simple owner immediately after the breaks in the chain of title or the present owner. Many of the title opinions reviewed by the author over the last 25-plus years do not state the exact date =tom which the affidavit of adverse possession is to track the adverse nature of :he possession of a record title owner. Other title opinions specifically only ask _or confirmation of adverse possession or the immediate past 25 years of the _wnership of the lands under examina-on. As stated previously, no title by adverse possession is a marketable title. und v. Emerson, 204 S. W. 2d. 639 ,Tex. Civ. App. - 1947, no writ hist.); Owens v. Jackson, 35 S. W. 2d. 186 (Tex. Cis-. App. - 1931, writ dism'd w.o.j.); .etas Auto Co. v. Arbetter, 1 S. W. 2d. 34 (Tex. Civ. App. 1927, writ disn J w.o.j.); Austin v. Carter, 296 S. W. 649 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1927, writ dissd) and Ailing v. Vander Stucken, 194 S. 'L- 443 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1917, writ wi'd).) That is, there is always the possit<- that a third party could raise a issue concerning ownership and ect the owner to probable litigation. L: not that the claimant would be sucTul, which deems the title unmar-JEEable. Rather, it is the probability of tion (to prove the facts and circum- stances constituting adverse possession) that causes the title to be unmarketable. Does this mean if there is even one break in the chain of title, no matter where in the chain of title it occurs, and reliance on an affidavit of adverse possession to "cure" same is required, then the client will have to rely on defensible title rather than marketable title? Yes. Lately, there has arisen a middle ground in large resource plays where many of the same title requirements are seen in multiple title opinions. More significantly, the client companies know that they will not be satisfying those redundant title requirements (old, outstanding deeds of trust, unreleased oil and ,as leases, etc.). To reduce the length of the title opinions, as well as costs, client companies are allowing the examining attorney to list those title defects that may occur in the chains of title and to point out that the client company deems those requirements waived. How the ownership of the mineral estate is set out in a title opinion is as important as the outstanding title requirements that need to be satisfied. That is, did the title examiner set forth the ownership schedule as it appears as of the close of the abstract/run sheet, or was the ownership schedule presented as if all title requirements had been or would be satisfied? This question is especially important if the client company initially attempts to verify that all of its lessors own a mineral interest in the subject property. If the attorney does not alert the client that, although it appears all mineral owners are leased, the record title does not confirm same and that only if all title requirements are satisfied will the ownership schedule be correct. In the author's experience, most client companies insist that the ownership schedule reflect all of the client company's lessors with title requirements to confirm same. The result is the same ultimately, but undue confidence can be imparted to the client company concerning whether or not the outstanding requirements were reviewed at the same time as the ownership schedule was reviewed. How the ownership schedule is set forth should be discussed with the client company or, in the opinion of the author, if not discussed, set forth as it appears of record subject to curative actions. DEFINITION OF CURATIVE Who Has the Risk? The owner of the original title opinion has the ultimate decision whether to accept the schedule of ownership as written (with no satisfaction of any title requirements), to satisfy all title requirements or to satisfy some and not others. That decision is solely one for the client with advice from the rendering attorney. The rendering attorney does not waive title requirements unless he or she wishes to accept all attendant risk associated with such waiver (including monetary loss if the title fails in whole or in part). If the attorney did not expect the title requirement to be satisfied, it should not have been placed in the title opinion. Once apprised of the risks of waiving the title requirement, the client must advise the rendering attorney of its decision to waive a title requirement. Thereafter, the attorney should note in a subsequent supplemental title opinion that one or more specific title requirements have been waived by the client company. Such notice thus qualifies the ownership schedule and its accuracy and correctly allocates the risk to the client company. Types of Curative Actions There are actually three different types of curative actions a title requirement may contemplate being carried out by the field Landman/attorney. These are searching for documents that were entered into and have not been found in the initial search of the public records, creating documents to satisfy the title requirement or performing legal actions such as litigation to satisfy a title requirement. The author has noted a significant increase in the submission of title run sheets that have significant breaks in the chain of title (failure to find one or more documents whereby a predecessor in title conveys its interest in the subject lands) or where the abstractor fails to read the pertinent document and obtain and furnish a referenced document found in the reviewed instrument. Specifically, most landmen today refuse to classify their abstracting duties as title research. Many refuse to even 29 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION furnish a statement of ownership as determined by them based on their initial title research. This position is curious since many times this same landman was responsible for leasing the potential mineral owners of the tract. How can a statement of potential ownership not be made for title examination purposes when it is expected that the examining Landman lease the correct parties? The answer most given is in two parts: mal- practice exposure and the fact that the abstractor does not run title; he or she runs names. The misstatement of mineral ownership by an abstracting landman, where the ownership statement is not properly qualified, could certainly result in potential liability if the ownership statement is incorrect. However, since most run sheets have lengthy and comprehensive restrictions on the reliance and use of the run sheet as well as limitations on legal liability written into each such run sheet, the author can find no reason not to include the landman's best expert opinion on mineral ownership. It is not given for reliance purposes but to assist the examining attorney in understanding how the run sheet was constructed and what interpretations the landman placed on different instruments in reaching a title conclusion. Let's be honest: The landman has already stated who he or she believes owns the mineral estate by leasing the parties appearing in the oil and gas leases covering the subject tract. Many abstractors admit to only running names. They do not even read the instruments that they furnish the examining attorney. If they had, they would have found contained in those instruments additional documents identified by volume or page which would further define the mineral ownership of the tract. The abstractors retained by the author were required to read each document with a highlighter identifying the grantor, The other significant error made in abstracting title is the use of the reverse index only. It has come to the author's attention in several significant busts that the run sheet furnished appeared to be premised on locating the present owners via the tax rolls and building the chain of title back in time using the reverse indexes. Certainly one can obtain a chain of title with no apparent title breaks using such a methodology. However, between the time that the earlier grantor conveyed the tract to the later grantee, it could have conveyed all or part of the mineral estate to a third party. Such a conveyance will not be picked up in the reverse indexes. Only if the complete chain of title is rerun from sovereignty in the direct indexes will all potential conveyances be located. In summary, the client company should specify that all abstractors prepare a schedule of mineral ownership, properly limited; that all instruments be read by the abstractor; and that all actual title research be based in part on the running of the mineral title from sovereignty using the direct indexes. Many title requirements call for the creation, execution and delivery of legal documents that, in the opinion of the examining attorney, will satisfy the outstanding title requirement. It is usually left up to the client company to determine who will prepare the document. Simply stated, if it is important enough that the examining attorney called for the preparation of a specific legal document to satisfy a title requirement, it makes no sense to let a third party prepare that document when the examining attorney knows exactly what information will satisfy his or her title requirement. This is especially true of affidavits as will be detailed later in the article. Can All Title Requirements grantee, property description, exceptions Ever be Cured? or reservations and the date of the instrument. The highlighting of these provisions ensured that the abstractor was aware of any mineral reservations as well as any documents referred to in the instrument of which the abstractor might not have been aware. Yes! Though rarely used today (and discussed in greater detail in the following paragraphs), the trespass to try title action, properly plead and with the correct attendant documentary evidence, will cut off all potential adverse owners of the mineral estate in a given tract of 30 land and will confirm title in the plaintiff(s) bringing the litigation. However, prior planning and timing are required to make the trespass to try title suit an effective title curative option. Liability for Not Determining the Correct Mineral Ownership If a mineral owner is not identified, and not leased, what effect does that have on the client company or lessee? It depends on whether the lands are pooled and/or if the missing unleased interest in under the drillsite tract. An unleased mineral owner under a lease well or a pooled well (drillsite tract only) becomes a cotenant with the other leased mineral owners and the lessee in that tract. (Wilson v. Superior Oil Co., 274 S. W. 2d. 947 (Tex. Civ. App. - writ ref'd n.r.e.) and (Wooley v. West, 391 S. W. 2d. 157 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1965, writ ref'd n.r.e.).) One cotenant may lease its interest in a tract of land without the consent of its other cotenant(s). Any cotenant or its lessee may commence drilling for oil and gas on the leased premises without the consent of the other cotenant(s). (Powell v. Johnson, 170 S. W. 2d. 273 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1943, aff'd).) More importantly, the entry by either cotenant onto the tract for drilling and production purposes is not deemed trespass since each cotenant has a co-equal right of possession (Byrom v. Pendley, 717 S. W. 2d. 602 (Tex 1986).) The failure to identify and lease an undivided mineral owner under a lease well or under the drillsite tract for a unit well will result in the payment of monies to the unleased cotenant (after recoupment of all drilling and producing expenses) (Byrom v. Pendley, 717 S. W. 2d. 602 (Tex 1986)) based on its undivided interest in the tract (in the case of a pooled unit, the unleased cotenant under the drillsite tract will be entitled to its ownership interest on an unpooled basis). Nondrillsite tract - An unleased mineral in a nondrillsire unit is not entitled to any share of production unless and until: It grants an oil and gas lease to one of the lessees who owns a working interest in the unit, and November !December 201] Land nan CURED TITLE OPINION the unit designation is amended to include the additional lease covering its interest with a pooling pro- vision. The parties to the unit can agree that the participation of the now leased mineral owner will be retroactive to the date of first production. In the absence of such agreement, the now leased mineral owner's participation in unit pro- duction will be from the effective date of the pooling designation amendment. (Union Gas Corp. v. Gisler, 129 S. W. 3d. 145 (Tex. Civ. App. 2003).) It grants an oil and gas lease to an oil and gas lessee and, if not voluntarily admitted into the unit, has the lease force pooled into the unit. Its right to participate is only effective from the date of the order of force pooling. (Railroad Com'n of Texas v. Pend Preille Oil & Gas Co. Inc., 817 S.W.2d..366 (Tex 1991).) THE SUPPLEMENTAL TITLE OPINION (CURING THE ORIGINAL TITLE OPINION) Definition A supplemental title opinion is written after an original title opinion has been rendered and may consist of either or both (1) a review of outstanding title requirements in light of curative materials submitted to the examining attorney or (2) an update of the ownership schedule from the last title opinion rendered based on all records filed from the closing date of the last title opinion. A supplemental title opinion may also be rendered for either drilling or division order purposes. Only after all title requirements have been deemed satisfied by the examining attorney may the client company rely fully on the ownership schedule with all attendant risk on the examining attorney and be assured of marketable title to the mineral estate. Any outstanding title requirement, or the requirement of reliance on facts outside of the chain of title to deem a title requirement satisfied, will leave the title potentially defensible but not marketable. There are three possible actions that can be taken by the examining attorney with respect to an outstanding title requirement in an original title opinion and for which curative materials have been submitted to the client company (examining attorney) for review: Waiver of title requirement Whether a client is justified in waiving a title requirement is a function of management's evaluation of the problem and whether it is willing to accept all attendant risks associated with the waiver. An attorney does not waive title requirements. If a waiver was appropriate by the examining attorney, the title require- ment should never have been placed in the title opinion in the first place. If a title requirement is waived, definitionally the title cannot thereafter be deemed marketable. At best, it would be classified as a defensible title. The examining Land in the right hands: Trust Mason Dixon Energy, one of America's largest, full-service land companies. Project Management • Negotiate and Acquire Oil and Gas Leases • Negotiate and Acquire Rights of Way Due Diligence • Lease Take-Off and Mapping • Abstract Preparation and Title Certification Negotiate and Acquire Permits For Geophysical Testing • Lease Records Management Obtain Permits from Federal, State and Local Agencies • State and Federal Lease Sale Representation Settlement of Surface Damages 101 Cambridge Place Bridgeport, WV 26330 Phone 304.842.9550 Fax 304.842.9552 - .adquartered in Bridgeport *--,h offices in Pennsylvania. 31 Lan Jinan CURED TITLE OPINION attorney can adjust the ownership schedule based on the client company's waiver and protect himself or herself from liability with the appropriate limiting language and assumptions made based on the waiver. For instance, if the title requirement was to furnish the probate materials for one of the potential mineral owners who died more than 80 years ago, and the client believes that all potential devisees have been located and leased, it may elect to waive the title requirement. The examining attorney can then choose one of the following: Satisfaction of title requirement The examining attorney, after a review of the curative materials submitted in connection with a title requirement, may deem that title requirement satisfied and, if necessary, adjust the ownership schedule accordingly. Conditional satisfaction of title requirement - The examining attorney may have called for a curative document involving an affidavit such as an affidavit of heirship. Definitionally, if an affidavit is involved in the curative process, the quality of title is diluted from marketable to at best defensible. It is up to the client company to accept the risk that the facts contained in the affidavit are accurate and correct. The author prefers to note such risk acceptance in the supplemental title opinion. The examining attorney may then note the appropriate change(s) in the ownership schedule assuming the risk decision by the client company was an accurate one. The author has personally made such title requirements and was furnished Tap Into Our Vast Reservoir Of Oil And Gas Knowledge. I" affidavits of heirship. The clie-company made the decision tc accept the facts contained in affidavits. Unfortunately, in ms-, than one instance, the heirshir affidavits were wrong. Properly identified risk decisions by th, client company - and the resultant incorrect assumpti, the examining attorney based those risk assumptions - relieves the examining attorney from liability due to a poor management decision to waive the title requirement with the resultant possibility of whole or partial title failure. How does the title attorney render a supplemental title opinion (with changes in ownership) where one or more title requirements have been waived? As previously discussed briefly, with properly identified assumptions of With over 30 years of experience,SMU Cox is the world's premier provider of oil and gas Executive Education. Decision makers and aspiring professionals in the major petroleum-producing regions turn to us for the CPE hours and skills they need to make a lasting impact on their companies a'.d their careers. Programs include negotiation, finance, accounting, strategy, leadership and r anagement. Factor in our unmatched alumni network and our association with the Maguire Energy Institute, and we're one valuable resource. Visit www.exed.cox.smu.edu or call 214.768.1616. In association with the Maguire Energy Institute. SMU f�����lf COX ExECuTIvTF EDUCATION Follow us on 91 Ui nv,:r _.ity wilI not discriminate in any employment practice, ,cation program or educational activity on the basis of race, color, religion, ral origin, sex, age, disability or veteran status. SMU's commitment to equal opportunity includes nondiscrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. 32 November / December 2011 Land in an I CURED TITLE fact flowing from the waiver by the client company, the examining attorney can thereafter change the ownership schedule to reflect such risk assumptions. Risk Decisions by the Client Company What are the bases upon which a client company may be justified in waiving a title requirement? The author has been able to classify four distinct foundations upon which a title requirement waiver may be initially justified although ultimately incorrectly made in hindsight. Factual risk A title requirement can be waived where the facts are unknown and can never be established. Example: Who were the heirs of a party who died in 1850? No one is alive today who can state with certainty who those heirs were. At best, the records and family can only guess. The risk assumed by the client company is that the facts assumed by the client company to be correct are ultimately determined to be incorrect and one or more mineral interests are unleased. Legal risk - A title requirement can he waived where the salient facts surrounding a title requirement are known, but the law on the subject matter is unclear. Example: The application of the Duhig principle to a factual situation, especially in light of the numerous potential exceptions to the rule. (See "Ding Dong Duhig is Dead" by the author.) Apparent risk - A title requirement can be waived where the salient facts and/or law are known and are against the waiver of the title requirement. That is, if ever discovered, title would fail. However, the client company does not believe that either the pertinent facts and/or the application of the law against it will ever take place - i.e., the client company will never get caught. An example is old title problems such as heirship where it is known that certain family members did not participate in a partition of the lands at issue. OPINION Money/Time - A title requirement can be waived where its satisfaction simply costs more than curing same would yield. Closely associated with the costs of curing is the time of curing a title requirement. Where, in the opinion of the client company, the cost of curing a title requirement exceeds the value of the loss or the time associated with such curative acts far exceed the yield to the client company for curing same, a client company may be justified in waiving that title requirement. Example: A small nonparticipating royalty interest owner under a nondrillsite tract in a pooled unit cannot be found. If the costs of finding such person far exceed what the lessee believes will be the risk if the owner were found and ratified the unit, then the requirement could reasonably be waived. The lessee's liability would only be from the date of ratification, not the date of first production. numerous other particular acts, particularly by the state of Texas, attesting that the aforesaid line is as before stated, thus is such line established as a matter of law. Any other holding would impugn the fidelity and integrity of each Attorney General holding office in the state of Texas, and so as to the Land Commissioners. (Harris v. O'Connor, 185 S. W. 2d. 993 at page 1014 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1944, no writ hist.).) After the patent is drafted but before it is delivered to the patentee, it must be registered in the land office's patent book. (Natural Resources Code §51.001 (Vernon 1985).) If a patent is not issued according to law and was not authorized by law nor made under color of law, it is void and those claiming under it acquire no title or right. (State v. Sneed, 181 S. W. 2d. 983 (Tex. Civ. App. -1944).) Patents are only required to be recorded in the General Land Office. Once recorded in the General Land Office, their recordation is notice to the world of the patent's existence. Nonwaivable Requirements (Mathews v. Caldwell, 258 S. W. 2d. 810 (Comm. Of App. - 1924).) Any Patents attendant documents that may assist in the interpretation of a patent (or early land grant) may not be filed for record in the General Land Office unless such deposition has been authorized by law. (Landry v. Robinson, 219 S. W. 2d. 819 Patents, as distinguished from early land grants, were instruments issued by the Republic or state of Texas whereby land was granted or conveyed by the Republic or state to a grantee. Patents are subject to the same rules as all written conveyances. That is, they must comply with the Statute of Frauds and adequately identify the grantor, grantee, the estate being conveyed and properly describe the lands made the basis of the patent for them to be valid. Compliance with the Statute of Frauds can be deemed, even as a matter of law, where a considerable period of time has passed and the State and all surrounding landowners have acquiesced in the title as located on the ground. (Harris v. O'Connor, 185 S. W. 2d. 993 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1944, no writ hist).) Exactness was difficult of attainment and should not be insisted upon, to the destruction of right ...... This answer is justified by over 100 years acquiescence by the Governments of Coahuila and Texas, the Republic of Texas and the state of Texas; not only by acquiescence, but by (Tex. - 1920).) The Fort Bend County Problem Early one morning, the residents owing land and homes in a survey located in Fort Bend County, Texas, woke up to find that they only owned two-thirds of their surface estate and two-thirds of their mineral estate. Since no case was filed nor legal decision reached, the author has only the following information furnished to him by the Fort Bend County clerk. An oil company wanted to drill on Blackacre. It commissioned a fee simple title opinion for Blackacre. One of the title requirements was to obtain a copy of the Mexican land grant on file with the General Land Office despite the fact that a handwritten copy of same was of record in the Fort Bend County Deed Records. The copy of the land grant obtained from the General 33 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION Land Office did, in fact, have noted in the margin that one of the original grantees had not performed his work and residence requirements (condition subsequent) and had in fact returned to Tennessee. This marginal notation was not found on the copy of the patent found in the Fort Bend County Deed Records. The marginal notation was evidently construed by the General Land Office as an affirmative action, on the part of the sovereign (Mexico), negating the title of the noncomplying party (undivided one-third interest). After discovery of the marginal notation, the state of Texas, as successor-ininterest to Mexico, declared that an undivided one-third interest in the entire survey was and had always been owned by the state of Texas. A constitutional amendment was passed allowing the revesting of the title to the surface estate. However, title today to the mineral estate (one-third) remains in the state of Texas. Curative Action - There is no curative action that can be taken! The original settler had an obligation to remain on the land for a specific period of time. Once he failed to perform that requirement, the sovereign (state of Texas) had no choice but to declare that title to the undivided onethird interest was forfeited and remained vested in the sovereign. It cannot be emphasized enough adverse possession does not lie against the state of Texas. (Harris v. O'Connor, 185 S. W. 2d. 993 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1944).) In the author's opinion, each fee simple title opinion issued should require that a copy of the complete patent or land grant file in the General Land Office be obtained and reviewed to confirm that all of the sovereign's title to the survey in question has been properly conveyed. It must be remembered that the copy of the patent found in the county clerk's office, depending on its age, is probably a handwritten copy of the patent furnished to the patentee and is not a copy of the patent that is filed in the General Land Office. Since the filing of the patent in the General Land Office, as well as what marginal notes or other materials are found in the patent 34 file, are notice to the world of their contents (Mathews v. Caldwell, 258 S. W. 2d. 810 (Comm. Of App. - 1924)), how can any responsible client company elect to waive a requirement that a copy of the patent and any other pertinent documents found in the General Land Office be obtained and reviewed? How can any examining attorney fail to place such a requirement in an original title opinion? The author has no answers to the foregoing questions but can state that, even where such a requirement is found in a title opinion, it is inevitably waived. Marketable title cannot be assured until the requirement set out is put forth in an original title opinion and has been satisfied? In the author's opinion, unless the requirement is satisfied, there remains a possibility that there is/are one or more facts located in the records of the General Land Office which, as with the survey located in Fort Bend County, Texas, could cause the title to fail in whole or in part. Result - the examining attorney cannot assure the client company that marketable title exists with the outstanding title requirement remaining unsatisfied. Any problems with the survey file, such as marginal notations or other communications found in the file, should be noted by the title examiner. Where such title problems exist, marketable title cannot be assured without additional acts of the General Land Office or, in the worst case, confirmatory litigation. Use and Occupancy Affidavit As a general proposition, an oil and gas lessee is charged with notice of conditions on the ground that are readily visible from an inspection of the surface of the land at issue. (Madison v. Gordon, 39 S. W. 3d. 604 (Tex 2001).) For instance, the existence of rivers, lakes, streams, cemeteries, buildings, railroads, roads, etc. can easily be found based on an on-the-ground inspection. Equally as important, parties in possession other than the record title owner can only be ascertained from an on-the-ground inspection. Last, and most important, confirmation that there are no producing oil and gas wells on the property at issue can only be confirmed by an inspection on the ground. Two Examples 1. Company A decided to drill a well in Montana. In fact, it did drill a well and made a significant oil discovery. Later, after the well was completed, the state of Montana called and congratulated Company A on its discovery. It also asked Company A why it did not get an oil and gas lease from the state on the riverbed of the Yellowstone River. The river had moved avulsively (and thus titles did not change), and the well was drilled exactly in the middle of the abandoned bed. A surface inspection of the drillsite tract would clearly have yielded evidence of the former existence of a river where the well was to be drilled. 2. Company A decided to drill a well on Blackacre. Its geologist went out on the wellsite when the well location was surveyed. He noted a producing well some 10 feet from the anticipated location that was separated by a barb wire fence. He believed that the well was on the same lease his well was to be drilled on, and thus he said nothing to the company. The well came in successfully. Unfortunately, the well was on a different lease, and no Rule 37 had been obtained. The well was shut in until appropriate damages were paid to the adjacent operator. This title requirement is uniformly waived. Even if the client company does not want to know any of the facts identified above, it is certainly interested in keeping damages due to drilling down to a minimum. It cannot do that if it does not have photographic evidence of the condition of the land before, during and after the drilling of the well. This can only be obtained by an actual visual and photographic record of the drillsite tract. Ask Company A if it wished it had done a surface inspection. With millions of dollars in drilling costs and even more millions in anticipated revenues, it only makes sense to eliminate as many risks as possible. The requirement of an affidavit of use and occupancy based on an actual surface inspection of the lands at issue should never be waived. Xovernber / December 2011 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION AFFIDAVITS General Principles As alluded to previously in this article, affidavits are governed by several important principles. Failure to follow these principles leaves the party relying on same with the possibility that the affidavit, although containing significant and important information, may not be admissible in a future court proceeding. The single most important decision that must be made by the examining attorney and company representative is he purpose(s) for which the affidavit is being taken. If it is never to be introduced mto evidence for any title purpose, why =o to the trouble to take the affidavit in the first place? Why nor reduce the facts to writing and submit them to the examining attorney for review with the caveat htat the client will have to assume all risk that the facts, as submitted, are correct? The validity or invalidity of a particu_ r affidavit, depending on the circumstances under which the relying party is attempting to use same (admission into evidence; basis for summary judgment; erliance upon for title purposes, etc.), _ften turns on the use of "magic words," =e absence of which can lead to less _an a desirable result. The following is discussion of a sampling of Texas case on various clauses and phrases as _Il as the legal issues that arise from -.e use or lack of use of certain "magic _Js" in affidavits. The rules of evi__-Ce and admissibility of affidavits are -serous and varied. What the author tried to do is summarize the major s in affidavit drafting that could lead ..rectly to the inadmissibility of any affi.iavit in a subsequent title suit. Stated zother way, why take what will be an =admissible affidavit when, with a little ck and forethought, a "title curative affidavit" can stand in futuro as an a rissible affidavit in a litigation setting if anLi when needed? If an affidavit is called by the examining attorney for curapurposes, the client company is well iced to consult with the examining ey to confirm that the facts necesfor review have to be contained in affidavit form. If so, why not have the ining attorney draft the affidavit to e that it can be used for the purposior which the attorney intends? g is more disappointing than b�n-e an affidavit, and its important be deemed inadmissible in a case ing title where the affiants are now br / December 2011 deceased. Where to get those facts now? With the foregoing in mind, the author offers the most significant problems with the admissibility of affidavits after their execution in a brief summary format. "Personal knowledge," "True and correct" ("magic words") - The failure to use the term "personally within knowledge of affiant" properly in an affidavit is, in a trial setting, a defect in form that must be objected to and the objection preserved for appeal if the affidavit sought to be admitted into evidence is objected to by the opposing side. Failure to object to the affidavit's admission for use of the words "on information and belief," "verily believes," etc. and the admission of the affidavit into evidence without such objection will cause the objection to be waived. (Choctaw Properties LLC v. Aledo ISD, 127 S.W.3d 235 (Tex.App. Waco 2003). See also Rizkallah v. Conner, 952 S.W.2d 580, 585 (Tex.App. Houston [1 Dist.] 1997).) "The affiant must positively and unqualifiedly represent the `facts' ... disclosed in the affidavit to be true and within his personal knowledge." (Brownlee, 665 S.W.2d at 112.[2]). Even though Tex. R. Civ. P 145 contains specific language to be used in affidavits, the cases cited above have not held that those magic words are the keystone of this review, but instead appraise whether the affirmation is such as to show that the statements are based on the affiant's personal knowledge and whether the statement is so positive as to allow perjury to lie. (Teixeira v. Hall, 107 S.W.3d 805, 809 (Tex.App. Texarkana 2003).) In the context of a summary judgment affidavit, courts have uniformly held that affidavits which are based on the affiant's best knowledge and belief do not meet the strict requirements of Rule 166a - they must state facts, not belief. Thus, such affidavits are held to constitute no evidence. (Teixeira v. Hall, 107 S.W.3d 805, 809 (Tex.App. Texarkana 2003).) An affidavit which does not positively and unqualifiedly represent the facts as disclosed in the affidavit to be true and within the affiant's personal knowledge is legally insufficient. (Brownlee v. Brownlee, 665 S.W2d 111, 112 (Tex. 1984); Burke v. Satterfield, 525 S.W2d 950, 955 (Tex. 1975).) The affidavits before us state that the affiant's statements are based on his "own personal knowledge and/or knowledge which he has been able to acquire upon inquiry" and, hence, fail to unequivocally show that they are based on personal knowledge. Additionally, the affidavits provide no representation whatsoever that the facts disclosed therein are true. Because of these defects, the affidavits are legally invalid and cannot serve as evidence in support of State Farm's claims of privi- lege. (Humphreys v. Caldwell, 888 S.W2d 469, 470 (Tex. 1994).) It is well settled law in this state that a controverting affidavit containing such words as "on information and belief," "knowledge and belief," "verily believes," "good reason to believe" and "believes to be true" are fatally defective. However, no court has ever condemned the use of the term "to his best knowledge." The term "within my knowledge" was approved in Coker v. Audas Inc., 385 S.W.2d 862 (Tex.Civ.App., Texarkana, 1964, no writ). (See also Knipe v. Rector, 463 S.W2d 769 (Tex.Civ.App., Fort Worth, 1971, no writ) and Rice v. Tucson Credit Union, 413 S.W.2d 833 (Tex.Civ.App., Texarkana, 1967, no writ).) It is the use of the word "believe" which is found to be objectionable by our appellate courts. The words "believe" and "knowledge" or "best knowledge" do not have the same meaning. (industrial State Bank of Houston v. Wylie, 493 S.W2d 293, 295 (Tex.Civ.App. Beaumont 1973).) Apparently, for an affidavit to be admitted into evidence, the test for its admissibility is whether it is based on the personal knowledge of the affiant such that, if the facts have been deliberately misrepresented, the affiant could be liable for perjury. Competency of the affiant: How the affiant came to know the facts - It is not enough that an affidavit shows that the facts are within the personal knowledge of the affiant. In addition, the affiant must demonstrate how and under what circumstances he or she obtained knowledge of the facts and why he or she is qualified to make such an affidavit. For instance, many affidavits of use and occupancy reviewed by the author for curative purposes contain a metes and bounds description of the property under examination and/or a plat of same. Nowhere in the affidavit is it stated that the affiant surveyed the property, caused the plat to be made nor how the affiant can state that both or either is accurate. Only the surveyor could 37 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION swear or testify as to the accuracy of a metes and bounds description or survey plat, thus raising a substantive issue of admissibility of the entire affidavit into evidence. It should be noted that failure to object to the admissibility of an affidavit due to a lack of competency on the part of the affiant results in the waiver of the defect. Many affidavits reviewed by the author contain the following statement: "Statements of fact and conclusions based on those facts personally within knowledge of affiant." Almost all of the affidavits whose admissibility was controverted and were reviewed by the author contained an identical or similar provision. The provision is an attempt to establish competency of the affiant as to the facts and conclusions recited in the affidavit by the affiant. Such a statement, standing alone, will not establish competency of the affiant. An affidavit must affirmatively show how the affiant became personally familiar with the facts so as to testify as a witness, and a self-serving recitation of such does not satisfy the requirement. (Villacana v. Campbell, 929 S.W.2d 69, 74 (Tex.App. - Corpus Christi 1996, writ denied). Goggin v. Grimes, 969 S.W2d 135, 138 (Tex.App. - Houston [14 Dist.] 1998).) Who is the affiant? How did he or she come into possession of the "facts" found in the affidavit? If an affidavit is to be relied on for title purposes, it simply must be based on facts personally ascertained by the affiant. Otherwise, the affidavit will not be admitted into evidence for the purposes for which it was taken. Conclusive statements - "One of the most often raised (and granted) objections to the introduction of an affidavit into evidence is that the affiant stated conclusions of law or fact and did not state or premise any such conclusions on the actual facts at issue. A conclusory statement, either of the facts or the law, where there are no underlying facts to support the conclusion, is a defect of substance and may be raised for the first time on appeal. This is to be distinguished from a defect in form where the objection is deemed waived if it is not raised at the time the affidavit is sought to be admitted into evidence." (Churchill v. Mayo, 224 S.W3d 340, 347 (Tex.App. - Houston [1st Dist.] 2006).) The rationale for such a rule is premised on the theory that, if an actual trial was being held and the affiant 38 testified with conclusions only, wholly omitting from his/her testimony any facts upon which the conclusion(s) were based, a court would have no choice but to disallow such testimony. The law is clear conclusions are permitted by affiants. However, they must be premised on full and complete facts that lead logically to the conclusion, especially if the conclusion is one of law. The objection that a statement is "conclusory" is an objection that is frequently made to challenge affidavits in summary judgment cases. (Johnson v. Bethesda Lutheran Homes & Servs., 935 S.W2d 235, 239 (Tex.App. - Houston [1st Dist.] 1996, no writ.) (Hedges, J., concurring).) There is much confusion about what this objection means. It does not mean that logical conclusions based on stated underlying facts are improper. That type of conclusion is proper in both lay and expert testimony. What is objectionable is testimony that is nothing more than a legal conclusion. (Anderson v. Snider, 808 S.W.2d 54, 55 (Tex.1991); Brownlee v. Brownlee, 665 S.W2d 111, 112 (Tex.1984).) To allow such testimony is to reduce to a legal issue a matter that should be resolved by relying on facts. Statements of legal conclusions amount to little more than the witness choosing sides on the outcome of the case. (Mowbray v. State, 788 S.W.2d 658, 668 (Tex.App. - Corpus Christi 1990, pet. ref'd). 952 S.W.2d 580 (Tex.App. - Houston [1 Dist.] 1997).) (Rizlallah v. Conner, 952 S.W.2d 580, 587 (Tex.App. - Houston [1 Dist.] heirs-at-law of the deceased fee si-_- mineral owner of the drillsite tract course, after the well was drilled a-._ completed, making 2 million cubic a day, the fourth "child" came for.: When confronted, the affiant statehe just knew his mother would ncwanted his sibling to have any in- in the "old homestead." Thus, n, -tion was made in the affidavit of _:undivided one-fourth unleased under the drillsite tract. Ultimate issue becomes whether the affiant interested party in the subject mar the affidavit. If so, a self-serving a, is inadmissible on a trial of the ma-for which it was issued under the rule. (Fenley v. Ogletree, 277 S.W.=_ 144 (Tex.Civ.App. - Beaumont Many corroborating affidavits a-often flawed as well in that they,-,--. deliver conclusory statements. Thathe affidavit issued by the corrobo-: affiant usually states that the affiar-- sonally knows the facts and conclu made in the main affidavit to be t-.and correct. Without a full renditi_ the facts and circumstances of wh'. how the affiant knows the facts cc tained in the main affidavit to be -the corroborating affidavit is of n� import and will not serve to make admissible the affidavit of the inte-_ party. More importantly, if the parr ing the corroborating affidavit is fawith the facts such that he can co-.- the main affidavit, why shouldn't -_. party give the main affidavit to th, exclusion of the interested party' 1997).) Interested Person The first instruction the author received from his mentors in writing title opinions and requesting curative documents was to never, never allow a family member or interested party give the affidavit in the absence of a corroborating affidavit by a disinterested third party. The why had a two-part answer. First, and foremost, in the absence of a corroborating affidavit, the family member or affiant, especially in heirship and family history affidavits, is probably an interested party. As such, the affidavit, and its contents, may very well be inadmissible in later cases where the heirship or family history is an issue. Second, family members tend to see "heirship" in a less than legal fashion. For example, in one case, the family member only listed three children in the heirship affidavit as being the intestate TRESPASS TO TRY TITLE Making the Unmarketable Title Marketable If a title to a tract of land is de-unmarketable due to outstanding , unsatisfied title requirements, can title be made marketable via the • cial process? Yes, a marketable tit' be reached and reached in every ti--opinion rendered. It was not too lc- _ ago, at the beginning of the author-legal career, that all wells were drill under titles found by the examinin_ attorney to be marketable titles. H, By the utilization of the Trespass T.-Title lawsuit (TTT Lawsuit) (Proper Code §22.001 et seq. (Vernon 1985 Jr was, in the past, more than r: _ tine, where outstanding title requ-_ ments called for information which November / Decembc- Lan din an CURED TITLE OPINION rendering of title opinions well in advance of spud date (at least six months). However, the term "business risk" had little meaning where a judgment confirming the marketable title to the oil and gas mineral estate in the client company's lessor(s) was confirmed via judicial decision. At some point in time, oil and gas companies dropped the TTT Lawsuit as a method of title assurance and turned to management title risk decisions to speed up the title opinion process. There is no doubt that such a decision process allows the client company to delay title examination until the last moment with whatever resultant title examination could never be completely verified, and thus would continually expose the client company to potential liability (leasing the wrong party or not leasing enough of the correct parties) to have the law department bring a TTT Lawsuit. Invariably, in less than 5 percent of the cases (the author's estimate), one of the problematic parties responded to the litigation. Such response affirmed the validity of the filing of the litigation as well as provided the opportunity for the client company to lease such parties' interests via protection leases. After the litigation was affirmatively concluded, usually with no opposition, the client company was assured that its leasehold title to the oil and gas leasehold estate was good as against the world. Is this kind of assurance expensive? No, not where the litigation was unopposed. Where opposed, the rationale was that the litigation would have taken place anyway but after the drilling of a successful well. Was the litigation time consuming? No, not unless opposed. It did require advance contingency planning and the savings may occur where a title opinion is rendered but not needed. Thus, apparently a balancing decision has been made: sacrificing a marketable title for a cost savings in unused title opinions. Given that hundreds of thousands of dollars are already committed and spent developing an oil and gas prospect and that up to several million dollars will be spent in drilling and developing same, the potential loss of 55,000 to $10,000 per unused opinion does not, in the author's opinion, appear to be warranted. How much is it worth to know, with absolute certainty, that the correct party has been leased and that no past ancient title problems can come back, after the discovery of oil and gas, to haunt the client company' Be assured, ancient title problems are still being litigated today. Problems that no one thought could or would ever see the light of day are, when large deposits of oil and/or gas are found, being brought and, at the least, subjecting the client company to uncertainty in its title, and in some cases, loss of lease and revenue. All of the curative actions above described require the obtaining of information and review of same by the examining attorney. The information obtained is subject to being challenged by any interested party and is not conclusive nor binding on any third party without judicial intervention. Even with the delivery of the called for information, the examining attorney cannot render a final supplemental title opinion which recites that marketable title is vested in the parties enumerated in the am II A FULL SERVICE LAND COMPANY SERVING NORTH AMERICA • Mineral and Surface Leasing • Right-of-Way Acquisitions • Seismic Permitting • Mapping/GIS Services • Mineral Ownership/Title Curative • Abstracts of Title ELEXCO LAND SERVICES, INC. Marysville, Michigan (800)889-3574 Olean, New York Canonsburg, Pennsylvania www.elexco.com -:bcr / Docember 2011 (800)999-5865 (724)745-5600 Landman CURED TITLE OPINION ownership section of the title opinion. That is, as long as the factual information remains judicially unconfirmed, there still remains a risk of litigation based on (1) a reasonable chance that a third party could raise an issue concerning the validity of the title to the estate against the apparent owner; (2) the quality of the parol evidence necessary to remove any doubt as to the validity and/or sufficiency of the owner's title could be contested; (3) the presumption of fact which, in the event of a suit contesting title, would probably become an issue of fact to be decided by a jury would still remain; or (4) the record discloses outstanding interests in other parties that could reasonably subject the owner to litigation or compel such owner to resort to parol evidence to defend the title against the outstanding claims. In Texas, the only judicial method of confirming marketable title in and to a tract of land, where there are outstanding title problems that render the title unmarketable, is to utilize the trespass to try title statute (Property Code §22.001 et seq (Vernon 1985).) THE JUDICIAL PROCESS The purpose of the TTT Lawsuit is to provide the exclusive method of confirming and vesting title to real property. (Hill v. Preston, 34 S. W. 2d. 780 (Sup. Ct. 1931).) The cause of action provides a procedure whereby all claimants to the title may be adjudicated and possession vested ("title as against the world"). (El Paso v. Long, 209 S. W. 2d. 950 (Tex. Civ. App. 1947, writ ref'd n.r.e.) and Slattery v. Adams, 279 S. W 2d. 445 (Tex. Civ. App. - 1955, no writ hist.).) Any final judgment rendered in such an action is conclusive as to the title and right of possession against all persons claiming from, through or under the person(s) against whom the judgment is rendered. That is, the judgment is conclusive of all adjudicated claims to the land or claims that could have been set up by the losing party. (Zapeda v. Rahn, 48 S. W. 212 (Tex. Civ. App. 1898, writ ref'd.) and Pennington v. Pennington, 145 S. W. 2d. 688 (Tex. Civ. App. 1940, no writ hist.).) TTT Lawsuit is a procedure by which rival claims to title or right of possession may be adjudicated. (King Ranch Inc. v. Chapman, 118 S.W.3d 742, 755 (Tex. 2003).) To recover in a TTT Lawsuit, the plaintiff must recover upon the strength of his own title. (Rogers v. Ricane Enter. Inc., 884 S.W2d 763, 768 (Tex. 1994).) The plaintiff may recover (1) by proving 40 a regular chain of conveyances from the sovereign, (2) by proving a superior title out of a common source, (3) by proving title by limitations or (4) by proving prior possession and that the possession has not been abandoned. (Ruiz v. Stewart Mineral Corp., 042806 TXCA12, 120500160.) When the pleadings and evidence show that the dispute between the parties involves a question of title, the trespass to try title statute governs the substantive claims. See Martin v. Amerman, 133 S.W.3d 262, 267 (Tex. 2004); see also Ely v. Briley, 959 S.W.2d 723, 727 (Tex. App. - Austin 1998, no pet.) (Trespass to try title is the exclusive remedy by which to resolve competing title claims to property). (Ruiz v. Stewart Mineral Corp., 202 S. W. 3d. 242 (Tex. Civ. App. 2006).) The case of Martin v. Amerman, 133 S.W.3d 262, 267 (Tex. 2004) is one of the definitive, modem Texas cases that outlines the general characteristics of the TTT Lawsuit. As a title curative tool, it is the ultimate methodology of assuring the client company that the title to the mineral estate, which it leased, is vested in its lessors and is a title that is good as against the world. The following quotes will explain the general tenets of the TIT Lawsuit such that the reader can readily recognize when the filing of same is appropriate. In this case we must decide whether a trespass-to-try-title action is the exclusive means to resolve a dispute between neighbors over the proper location of a boundary line separating their properties, or whether a declaratory judgment action is also an appropriate way. We hold that the Texas trespass-to-try-title statute governs the parties' substantive rights in this boundary dispute and that they may not proceed under the Texas Declaratory Judgments Act to recover attorney's fees. (Martin v. Amerman, 133 S.W3d 262, 267 (Tex. 2004).) The Declaratory Judgments Act provides an efficient vehicle for parties to seek a declaration of rights under certain instruments, while trespass-to-try-title actions involve detailed pleading and proof requirements. (See Tex.R. Civ. P. 783809.) To prevail in a trespass-to-try-title action, a plaintiff must usually (1) prove a regular chain of conveyances from the sovereign, (2) establish superior title out of a common source, (3) prove title by limitations or (4) prove title by prior possession coupled with proof that possession was not detailed and formal, and require a plaintiff to prevail on the superiority of his title, not on the weakness of a defendant's title. (Land, 377 S.W2d at 183.) (Martin v. Amerman, 133 S.W.3d 262, 267 (Tex. 2004).) For the foregoing reasons, we again decline to recognize a substantive distinction between title and boundary issues, this time for the purpose of allowing alternative relief under the Declaratory Judgments Act. We conclude, as did the court of appeals, that the trespass-to-trytitle statute governs the parties' substantive claims in this case. The statute expressly provides that it is "the method for determining title to ... real property." (Tex. Prop. Code 22.001(a); see Ely v. Briley, 959 S.W.2d 723, 727 (Tex. App. Austin 1998, no pet.); Kennesaw Life & Accid. Ins. Co. v. Goss, 694 S.W.2d 115, 118 (Tex.App. Houston [14th Dist.] 1985, writ ref'd n.r.e.).) Accordingly, the Martins may not proceed alternatively under the Declaratory Judgments Act to recover their attorney's fees. (Martin v. Amerman, 133 S.W.3d 262, 267 (Tex. 2004).) Title examination attorneys do not make the risk decisions underlying curing or waiving title requirements. However, it is not an excuse that management cannot plan ahead such that drillsite tract title examination cannot be concluded with enough time prior to lease expiration to file a TTT Lawsuit. Severe and potentially large title losses do not have to take place. They can be judicially prevented via the use of the TTT Lawsuit. About the Author: Terry E. Hogwood, an attorney, runs a solo oil, gas and title-related practice in Houston, providing legal advice for oil and gas clients covering both onshore and offshore legal matters. He also renders day-to-day legal advice on lease maintenance problems, operating agreements, farm-ins and farm-outs and drilling agreements with heavy emphasis on Texas title matters including the rendering of stand-up title opinions. He is a member of the Houston Association of Petroleum Landmen and AAPL, receiving AAPL's Education Award in 1993. A member of the Texas Bar Association, he served as founder and first chairman of the Oil, Gas and Mineral Law Section of the Houston Bar Association. Hogwood received his bachelor's degree from Texas A&M and his J.D. from Baylor Law School. abandoned. (Plumb, 617 S.W.2d at 668 citing Land v. Turner, 377 S.W2d 181, 183 (Tex.1964).) The pleading rules are November/December 2011