host1-1

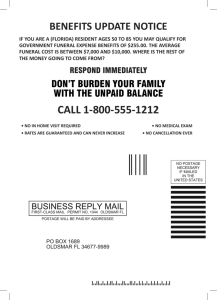

advertisement