Basic Memory Processes

advertisement

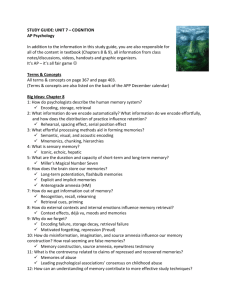

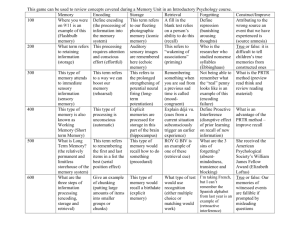

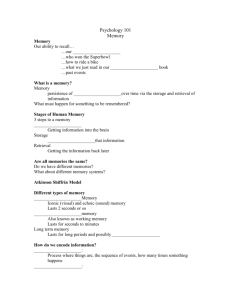

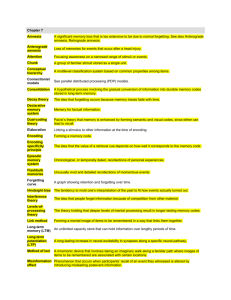

Memory Memory is the process by which we acquire, store, and later retrieve information. It serves several functions: 1) provides our consciousness its continuity (the story of our life in a continuous fashion) 2) enables us to adapt to situations by letting us call on skills and information from our past experiences (what if every time we got into a car, we couldn’t remember how to drive? How to eat? Tie our shoes? Talk?) 3) enriches our emotional life by letting us remember past moments from our life (both good and bad). Example: The case of H.M., a Connecticut factory worker, who had surgery to correct severe epilepsy in 1953, at the age of 27. This surgery involved cutting out an area of his brain. When the operation was over, he no longer had the ability to add information to his long term memory, although his short-term memory was fine. In other words, he could still do things like talk or drive a car, but he would have no memory of doing them. When a relative died, he would grieve anew every morning upon being told that the person was dead. He couldn’t remember meeting new people and couldn’t remember events that happened even half an hour ago. Until he died, he thought he was 27. BASIC MEMORY PROCESSES Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968) compared human memory to that of a computer. They say there are three stages in the memory process: encoding, storage, and retrieval. Encoding: This is the first stage, in which information is transformed or coded into a form that can be processed further and stored. We don’t remember everything. Encoding is affected by the meaningfulness of an item, its imagery value, and personal relevance. When you type on a computer, the computer turns the actions into code (zeros and ones) that it can understand. You do the same thing with information that you encounter and want to remember. **Only things that are meaningful to us get encoded. Remember selective attention from the Sensation & Perception section? We can’t process all 11 million bits of information that we see every second; we encode only about 40. Encoding can be either automatic or controlled (remember the two levels of processing from the States of Consciousness section). We can automatically encode things without really being aware of it, or we can really concentrate in order to get something encoded. Storage: The second stage of memory process, in which information is placed in the memory system. This stage may involve either brief or long-term storage of memories. Retrieval: the third stage of memory, in which things that have been stored in memory are brought into consciousness. Problems with retrieval can occur, and we may forget things. 1 Computers tend to be more perfect than humans in this area—if you ask a computer to retrieve something, it will (usually) retrieve it. Atkinson-Shiffrin Model: Information-Processing Model In addition to specifying the basic memory processes of encoding, storage, and retrieval, Atkinson & Shiffrin also described three ways that memory is stored: sensory memory, shortterm memory (also includes a working memory), and long-term memory. STORAGE SENSORY MEMORY Sensory memory is a memory or storage of sensory events such as sights, sounds, tastes, smells, with no further processing or interpretation. You’re aware that you’ve sensed something, but you don’t think anything further about it. Sensory memory preserves information in its original sensory form for a brief time. You probably have a sensory memory for each sense. Iconic memory is visual memory. The visual things you remember are called traces. Sperling (1960) presented three rows of letters to subjects for .05 seconds. The letters were as follows: NBFQ ZRTP KDVG He asked subjects to recall the letters. They could usually recall four or five but knew they had seen more than that. However, the image faded too fast for them to name the letters. Was it due to a storage capacity problem of iconic memory? To answer this question, he asked subjects to name the letters in only one row. He sounded different pitches of tones to signify different rows. When he sounded the tones first, the subjects knew to pay attention to the next four letters he displayed because they were all in a row. When the tone sounded afterward, they had to rely on their iconic memory to remember what they had just seen. After a brief delay, they could recall an average of 3.3 letters (out of 4 per row). So 9.9 of the 12 letters were stored in iconic memory. That’s basically the capacity of iconic memory. If the delay was longer than 1 second between seeing the letters and having to recall them, the subjects could only recall 4 or 5 letters out of the 12. Bottom line: the image of the visual stimulus fades quickly from iconic memory. Iconic memory lasts for about one second. Echoic memory is auditory memory. It normally lasts for about 2 seconds and is necessary for comprehending many speech sounds. When you hear a word pronounced, you hear individual sounds, one at a time, although you don’t realize this. You can’t identify the word until all the sounds have been retrieved. Obviously, this takes place at lightning speed. For example, when you hear the sound “Kit,” you don’t know if the rest of the word is going to be kitten, kitchen, kit-kat bar, etc. until you hear the rest of the word. You don’t recognize it until it’s in its whole form. All information is probably processed on some level, even though not all of it gets encoded. It means we attend to everything—every sensory experience we have. We know that everything is probably processed because of the following bits of evidence: 1) Flashbulb memory (also called “redintegration”): an episode of very detailed recall, including background factors. Think about a very vivid memory you have. For instance, 2 where were you when you first heard about the attacks on 9/11? Most people remember this in great detail—where they were, who told them, what they felt like, etc. Typically, when you have a memory that is of some significance to you, you will recall all sorts of background information along with the actual event—what you were wearing, specific smells in the air, how the air felt against your skin, etc., etc. It could be a more personal memory, such as grandparent’s death, a sibling’s birth, a special birthday party, or just a random memory that sticks out in your mind for some reason. This vivid snapshot of memories is called flashbulb memory because it’s like being in a dark room and someone suddenly flashes a flashbulb for a second. Everything becomes illuminated, and you remember a lot of things you saw. Sometimes memories are cued by specific sensory cues, called souvenirs. Souvenirs are anything that cues a certain memory—it can be music, certain smells, the way someone says a specific phrase. You can recover many memories that you thought were long-since repressed by encountering souvenirs. There’s a question, though, about how reliable such memories are. Any time you have a sense of déjà vu, it’s likely that you are encountering some souvenir, but you can’t quite bring the memory up. 2) Selective attention: Another way we know that all information gets processed is by selective attention—paying attention to certain things around you and excluding other sensory input. Example: the cocktail party phenomenon: you’re at a large party, involved in conversation with someone, but you hear many other conversations going on around you. All of a sudden you hear your name mentioned across the room, and you quickly turn around to see who’s talking about you. You’ve been attending to these other conversations the whole time, but you usually don’t realize it until something catches your ear (or eye). SHORT-TERM MEMORY (STM) Once information has been attended to or selected from sensory memory, it’s transferred to our conscious awareness. According to Atkinson & Shiffrin, before something can make it to longterm memory, it has to be processed in working memory first. Working memory is a very limited capacity memory store that lasts only for 30 seconds or so. Why is working memory so short? 1) Unless memories are practiced or rehearsed, they become weaker and fade way; and 2) to make room for new, incoming information, most information is subsequently forgotten. There’s only so much room on your working memory “chalkboard,” so you can only attend to things for a very short period of time. Also, you can only hold information that has 7 plus or minus 2 items in it. That’s why phone numbers have only seven numbers (except for area codes). One way to increase the capacity or working memory is to group items together in a meaningful unit. This is called chunking. Instead of memorizing area code 770 as 7-7-0 (3 separate items), think of it as a whole, 770, which reduces it down to one item in your working memory. Also, you memorize your SS# as 3 chunks, not 9 items. Exercise: Try this on a friend. Tell him or her, “You have 30 seconds to memorize the following group of letters: Listen first, attend to the letters, and then write down as many as you can. C-B-S-I-B-M-C-N-N-G-G-C-D-O-A. This string of letters has 15 items in it, way more than you can recall in working memory. Now I’m going to repeat the same string of letters, but 3 I’m going to say them in a different way: CBS-IBM-CNN-NGC-DOA”. Here you have five chunks of 3 letters each, and they’re meaningful chunks, so your friend should be able to remember them better. LONG-TERM MEMORY (LTM) This memory stage has a very large capacity (unlikely to ever be used up) and the capability to store information relatively permanently. People are not sure whether all memories are stored in LTM or not. How does information get into long-term memory? The answer is rehearsal. There are 2 types of rehearsal: 1) Maintenance rehearsal: works well when we want to maintain a memory for a short period. Basically ensures that a memory is saved until it is used, and then it’s discarded. Maintenance rehearsal can be achieved by simply repeating material. Repeat Domino’s number over and over as you make your way to the phone. Repeat someone’s name at a party until you can remember it, at least until the end of the party. 2) Elaborative rehearsal: adds meaning to material we want to remember and integrate it with information already in LTM. Example: You meet a girl named Ann at a party. She’s wearing a sweater from J.Crew you thought about ordering it. You have a cousin named Ann who has the same color of hair as the Ann you’ve just met. By making so many associations with Ann at the party, you’re likely to remember her. When you engage in elaborative rehearsal, you cement associations between what you’re learning and what’s already in your LTM. Information is not just stuck in your memory haphazardly. Without an organized LTM, trying to find information would be like trying to find a needle in a haystack. There are two basic findings that are clear: 1. Learners attempt to organize material (called subjective organization) to help them learn even when the material is not originally organized; and 2. Organized material is easier to learn. When I was in college, I used to use different colors of highlighters to highlight my notes. I’d use blue for broad topics, orange for the next level of topics, pink for important terms, and yellow for the most detailed things I had to remember. When it came time for a test, I could remember the different highlighter colors and the words that I needed. When I got to grad school, I retyped and organized all of the day’s notes every day. It was time-consuming but well worth it. The two broad categories of long-term memory 1. Nondeclarative or procedural memory. Memories we use in making responses and skilled actions. Memories of how to do things, like riding a bike, driving a car, tying your shoes, typing, changing a diaper in your sleep. Once you learn these things, you’re unlikely to ever forget them (until you get old and get Alzheimer’s dementia). Procedural memory is an implicit memory, one you have and use without awareness of it. 4 2. Declarative memory. This includes memory of facts and personal events. Declarative memory is divided into two subcategories: 1) semantic memory and 2) episodic memory. Declarative memory is explicit, meaning that you are consciously aware that you are trying to remember something. The two types of declarative memory Semantic memory: Semantic memory is memory for general knowledge. This memory is often organized in some fashion. In your memory, there is hypothesized to be something called a semantic network, which are concepts joined together by links (remember the souvenirs—they represent a link between two memories). When one memory, concept, or fact is accessed, it will trigger the retrieval of other concepts that are related to it. For instance, what do you think of when I say 1492? Your first thought is “Columbus discovered America. Then you think things like, “Columbus had 3 ships, the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria. His trip to the Americas was funded by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. He thought he was going around the world, but he actually ended up in West Indies.” That one date, 1492, activated all of those facts in your mind. This is called spreading activation—where the retrieval of one “node” in memory stimulates the activation of related nodes. Episodic memory: memory of one’s own personal experiences. These also may be organized in “episodic networks,” and thinking about one personal memory may cause you to think about another. (Remember the flashbulb memories, souvenirs, etc.) Ways to Improve Memory 1. Use mnemonics or memory aids, especially those that use visual imagery or organizational devices. 2. Use visual imagery to help you remember things. If you want to remember the words “green,” “piano,” and “carrot,” visualize a rabbit eating a carrot while sitting at a green piano. 3. Make up a jargon or song about what you’re trying to remember (e.g., the “Days of the Week” song in preschool) 4. Use acronyms: ROY G BIV for the colors of the rainbow, HOMES for the five Great Lakes, etc. Role of Emotion in Memory Stress hormones cue the brain that something important is happening and needs to be remembered (e.g., in flashbulb memories). The amygdale boosts activity in the hippocampus, where new memories are formed. Stronger emotional events produce stronger memories. 5 Where in the brain are memories stored? As far as we know, there is no single memory storage area in the brain. Different areas seem to be involved. The hippocampus (part of the limbic system, along with the amygdale) is responsible for forming new memories. It is active during slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4). The greater the hippocampus activity during sleep, the better your memory will be the next day. So it’s really counterproductive to stay up all night studying for a test. Memories aren’t stored in the hippocampus, though. Instead, the hippocampus serves as a sort of “loading deck” for new memories before they’re shipped to the cortex. Parts of the frontal and temporal lobes seem to be involved in memories, but again, there is no single memory storage area. We know this because if you train a rat to run a maze and then take out different parts of its brain, it can still remember how to run the maze. Some memories are held in the left hemisphere and others in the right. The cerebellum also seems to play a role in memory. It appears to hold procedural (implicit) memories. So your memories for how to do things appear to be stored in the cerebellum. Memories formed from classically conditioned responses also seem to be held here. Ebbinghaus’s research Ebbinghaus did experiments on memorizing lists of nonsense syllables to see how long it took him to forget them. He found a huge drop in retention within the first few hours, and more than 60% was lost after 9 hours. Ebbinghaus concluded that The amount remembered depends on the time spent learning We learn and remember better when it’s spaced out over time (called the “spacing effect”) Cramming (called”massed practice”) is not as effective as “distributed study time.” Cramming may produce speedy short-term memory that might stay in there for the duration of a test, but it won’t stay in memory long-term. Learning can involve a combination of STM and LTM. Here’s a little experiment you can do on someone. Verbally give them a grocery list such as this one and ask them to write down as many as they can remember: MILK, APPLES, CEREAL, BREAD, CHEESE, JOCK ITCH CREAM, PORK CHOPS, POTATOES, COOKIES, SPAGHETTI, BUTTER, and POPCORN. They should be most likely to remember milk, popcorn, and the jock itch cream. Why? The primacy effect is the tendency to remember the items near the beginning better. (“We the people,” “Fourscore and seven years ago”) This may reflect long-term storage and rehearsal. The recency effect is the tendency to remember things at the end. This probably reflects STM storage. If you remembered the jock itch cream, it’s because of the von Restorff effect—the tendency to remember things that are strange or that stick out in a list. A similar concept to the primacy and recency effect is something called interference. This is competition from other material. It’s much more of a problem when the material is similar. 6 There are two types of interference: 1. Proactive interference: when something you’ve already learned interferes with something new that you’re learning. Example: Learning languages. I had learned Spanish in high school and then tried to learn French in college, and at first I kept calling things in French class by their Spanish name. 2. Retroactive interference: when learning something new impairs the retention of previously learned material. Example: Learning new lists of names when you had already learned one that was different. You’ll remember only the most recent list that you learned. Or, in the language example, eventually I forgot most of the Spanish I’d learned in high school, and I only remembered the French. (Now I remember only a few words from both languages but often don’t know whether they’re French or Spanish.) RETRIEVAL Retrieval involves getting something out of memory. It can be very frustrating when you fail to get something out of memory that you need. Think of the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. This is the temporary inability to remember something you know, accompanied by the feeling that it is just out of reach. What can you do to help you retrieve something? Use retrieval cues— anything that helps you gain access to memory. Think of the first letter of the name, occupation, anything that may provide a cue or tap into some LTM organization. Also, use context cues—go to the physical context into which an event or thought occurs. Example: taking an exam in the same room that you learned the material in (the classroom). Having a dress rehearsal for a play. Recreate your mood or state when the event took place (only works sometimes). State-dependent memory is improved recall that is attributed to being in the same emotional state during encoding and subsequent retrieval. Some researchers have found evidence of it, but some have not, so there are doubts about this effect. Some research has been done about the effects of marijuana on learning and recall. Subjects did recall more when learning and recall were in the same state (stoned vs. not stoned), but performance in the drug condition was lower overall. The problem here is that marijuana appears to interfere with the memory process, as does alcohol. Studies show that what was learned when drunk was best recalled when drunk, and what was learned sober was best recalled when sober. There’s also some evidence for mood-congruence effects—memory is better for information consistent with your mood. If you’re happy, you tend to recall happy information. If you’re sad, you’ll recall more unpleasant information. Think about being in a depressed state. When you’re depressed, you remember more pessimistic things and think more negative thoughts about yourself, which only makes your depression worse. It’s a vicious cycle. FORGETTING Ebbinghaus was one of the first people to conduct experiments with forgetting. He memorized huge lists of nonsense syllables and then recorded how fast it took him to forget them. He found that there’s a huge drop in retention during the first few hours, and by nine hours, he had forgotten more than 60% of the material he had learned. Of course, his experiment didn’t have 7 much external validity since he was learning nonsense syllables, and most of what we learn is meaningful. There are three ways to test memory: 1. Recall—people have to reproduce material without any cues (essay tests, fill-in-theblank). This is the hardest type of test. 2. Recognition—people get to select information from an array of options (multiple choice test) 3. Relearning—memorize a second time and see how much time and effort are saved. It takes a much shorter time to relearn something when you’ve already been exposed to it once. Example: Memorize a list of words. After awhile, you’ll forget them, but if you try to learn them again a second time, it’ll take you much less time to memorize them. Why do we forget? 1. Maybe we code things ineffectively. We may forget because we never encoded the information at a very deep level to begin with. 2. Interference--proactive and retroactive interference. Much more of a problem when the information is similar. 3. Amnesia. A major problem with research on amnesia is that researchers don’t even agree on how to categorize types of amnesia. Some classify patients based on the origin of amnesia: head injury, alcoholism, etc. Some classify them on the area of brain damage, and some on the functional deficit of the patient. Three types of amnesia can result from a blow to the head: Anterograde amnesia is when a person loses memory for events taking place after the injury (Mmenomic device here: Anterograde –After.). May lose ability to remember verbal material or have trouble with visual-spatial learning. May be global, encompassing all types of behaviors, and it may be irreversible, meaning that you have lost abilities that will never be recaptured. Retrograde amnesia is forgetting things or events that took place before the injury. (Think “Retro” as meaning “back in the past…”vintage.”) Typically, the older memories come back, but the most recent memories may never be recovered. You may never remember the accident itself or the events immediately leading up to it. The third type of amnesia is called posttraumatic amnesia. This is a relatively confused stage during which the patient may have difficulty keeping track of ongoing activities, knowing where they are or having material presented to them. The patient may cycle through periods of lucidity and confusion, making the diagnosis of posttraumatic amnesia very difficult. The long-range prognosis is usually disappearance of posttraumatic amnesia, disappearance of most of the retrograde amnesia except for the most recent events, and an uncertain recovery from anterograde amnesia. The degree of recovery from the anterograde amnesia depends on the degree of injury to the brain. 4. Motivated forgetting—repression. Keeping disturbing thoughts buried in the subconscious. Child sexual abuse—as you all know, recovery of repressed memories has become quite common. Many people are now remembering episodes of sexual abuse that took place 10 or 20 years before. It has caused quite a stir in the psychological community. Some psychologists think that this is a valid phenomenon; others question 8 the validity of recovering a repressed memory. They don’t think that people are lying. However, they do believe that some people in a highly vulnerable emotional state may be especially prone to accept even slight suggestions made by an understanding therapist and then “reconstruct” memories that didn’t even happen. Other Interesting Facts about Memory Autobiographical Memory: Memory of our own lives (similar to episodic memory). When does this start? Usually in the 3rd or 4th year of life, although a few people can remember events even earlier than that. It’s thought that we can’t remember things before we’re 3 or 4 because before that age, we lack several things: 1 ) a self-concept, without which we have no personal frame of reference necessary for autobiographical memory; 2) the brain structures necessary for such memories are not developed in the first two years of life; 3) language with which to express these memories. The inability to remember things during the first two years of life is called infantile amnesia. However, growing evidence suggests that we actually DO remember things from the first two years, but we can’t put them into words because we didn’t have language then. Girls, who usually learn language a little bit before boys do, typically have earlier first memories than boys do. There’s a cultural difference as well. American children have earlier first memories than Asian children do, probably because in the Asian culture, it’s considered impolite to talk about yourself or focus on yourself too much. For first memories to become really solidified, an adult needs to help the child “construct the story” and fix the event in memory. Asian parents are less likely to do this because it’s just not a cultural norm there. “Photographic memory”—You’ve probably heard some people say that they have a photographic memory, where they can look at something once and remember everything about it. This is misleading. There is something called eidetic memory, which is often confused with photographic memory. People with eidetic memory have an unusually high degree of recall of details. It’s more common in childhood than in adulthood. 8% of elementary school children have it, but then it fades. People with eidetic memory still make memory errors, just not to the same degree. It has something to do with how much people use language. The more adept you become at using language, the more eidetic memory decreases. There’s also a positive correlation between eidetic memory and mental retardation, brain damage, and autism (remember Kim Peek, the autistic savant who inspired Rainmaker, and his seemingly “photographic” memory). False memories I have a very vivid memory of my dad’s leg catching on fire in our backyard when I was about 5 years old. He was wearing an ugly orange jumpsuit that men used to wear in the 1970s, and I remember him screaming and rolling around on the ground. My mother grabbed an army blanket from our shed and threw it around his leg to put out the fire. I would swear this event actually happened…but it didn’t. Dad never caught on fire. I have no idea where the memory came from. False memories have specific detail than real memories. They’re confined to the gist of the situation Once they’re formed, they can be very persistent and outlast real memories. Wiseman et al. (1999) staged 8 seances, each attended by 25 people. During each session, the “medium” 9 urged everyone to concentrate on moving the table. Although it never moved, he suggested it had, saying “That’s good. Lift the table up. That’s good. Keep concentrating. Keep the table in the air.” When questioned two weeks later, 1 in 3 participants recalled actually having seen the table levitate. Another study…Stephen Lindsay et al. 2004 Planted false memories of a 1st grade event in undergrads. Subjects were led to believe that they had gotten into trouble with a friend for putting Slime in their teacher’s desk. Each participant was led to believe that his/her parents had provided the following narrative (customized with their own name and the name of the first-grade teacher): I remember when “Jane” was in 1st grade, and like all kids back then, Jane had one of those revolting Slime toys that kids used to play with. I remember her telling me one day that she had taken the Slime to school and slid it into the teacher’s desk before she arrived. Jane claimed it wasn’t her idea and that her friend decided they should do it. I think the teacher, Mrs. Smollett, wasn’t very happy and made Jane and her friend sit with their arms folded and legs crossed, facing a wall for the next half hour. A picture of the subject’s first-grade class accompanied the narrative. 2/3 of the subjects developed false memories of this event. In fact, they expressed disbelief when told it was a false memory, saying they actually remembered it happening. Children and false memories: Study asked 3-year-olds to show on anatomically correct doll where the pediatrician had touched them. 55% indicated the genitals or anal region, even though none had had an examination of these parts. In another study, Ceci and Bruck had a child choose a card from a deck of possible happenings and an adult then read from the card. The adult said, “Think real hard. Tell me if this has ever happened to you. Can you remember going to the hospital with a mouse trap on your finger?” After 10 weekly interviews with the same adult repeatedly asking the children to think about several real and fictitious events, a new adult asked the same question. A full 58% of the preschoolers produced false (and often vivid) stories regarding one or more of the events they had never experienced. **Interviewers of children have to be very careful to use neutral, nonsuggestive language. Children are especially accurate when they have not talked with involved adults prior to the interview and when their disclosure is made in a first interview with a neutral person who asks nonleading questions. 10