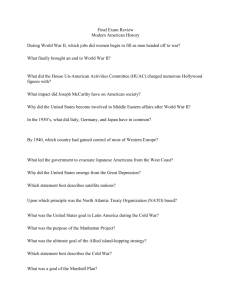

Eisenhower and Kennedy

advertisement

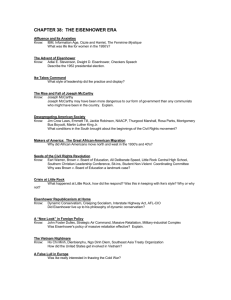

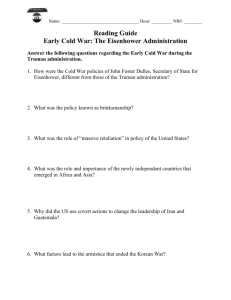

Eisenhower and Kennedy Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy are often held up as symbols of two radically different eras: the tranquil, prosperous '50s and the tumultuous '60s. Nonetheless, Kennedy himself was a product of the Eisenhower years and his politics, when scrutinized, are not always as progressive as the Kennedy Myth maintains. These notes examine the domestic policies of Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy as well as America's move away from the politics of tranquility. Some questions: 1) Why did America "like Ike?" 2) Compare and contrast the public image of Adlai Stevenson and Harry S Truman. 3) What was "dynamic" about Eisenhower's "conservatism?" 4) Who was a more "dynamic" president: Ike or JFK? The Campaign of 1952 Dwight David Eisenhower (1890-1969), known as "Ike," was President of the United States from 1953-1961. During World War II, he had been supreme commander of the Allied forces, directing the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944 and overseeing the final defeat of the Nazis. He later organized the military forces of NATO. At war's end, Americans were weary of strife, war, economic depression, and politics. Ike seemed untainted and his popularity was so high, that in 1948, both the Democrats and the Republicans wanted him for a presidential candidate. At the time, he refused both offers, saying that he did not find it appropriate for a general to involve himself in the political arena. However, he changed his mind in 1952, accepting the Republican nomination. Eisenhower made opposition of U.S. military involvement in Korea the center of his campaign, although he had supported President Truman's decision to enter Korea. Eisenhower also attacked the Truman administration for its soft stance on Communism and its alleged corruption. He developed a formula to describe his plan of action: K1C2. By this, Ike indicated that he intended to take care of Korea first, Communism and Corruption second. Eisenhower promised "I shall go to Korea" and, although he never said what he would do once he got there, it sounded like a sound plan to the American public. If General Eisenhower promised to go to Korea, the war would soon be over. The Democratic party drafted Adlai E. Stevenson, governor of Illinois, to run against Eisenhower in 1952 and again in 1956. Stevenson, a reluctant candidate, appealed to upper crust intellectuals and pseudo-intellectuals, but could not compete with Ike's immense popularity. Eisenhower's broad appeal was echoed in the simple slogan of his campaign buttons and posters: "I Like Ike!" Eisenhower's running mate was Senator Richard Nixon of California. A scandal regarding Nixon's campaign fund briefly threatened his candidacy. It was charged that a millionaire's slush fund was being diverted to Nixon's personal bank account. Nixon saved his place on the ticket by making an impassioned televised speech. He denied accepting any money under the table, but admitted that his family had accepted two unsolicited gifts. His wife, Pat, had been given a "plain Republican cloth coat," and his daughter had accepted a black and white cocker spaniel puppy she had named Checkers. Full of emotion, Nixon said to the American people: "I'm not going to break that little girl's heart by taking away that dog." Eisenhower defeated Stevenson easily in 1952, receiving over 55% of the popular vote. It soon became clear that Ike's view of the presidency was quite different from that of his immediate predecessors. Ike didn't believe that the President should be an agent of social reform, as had been the case with the New Deal and the Fair Deal. When asked why he wasn't sending more bills to Congress, Eisenhower replied, "I don't feel like I should nag them." "Dynamic Conservatism" Instead, Ike advertised his program as "Dynamic Conservatism," also known as "modern Republicanism." By dynamic conservatism, Eisenhower meant: 1. Budget cutting 2. Support of big business 3. Returning federal functions back to state and local levels Stated Ike: "I will be a conservative when it comes to money matters and a liberal when it comes to human beings." Eisenhower's choice of cabinet members demonstrated his support of big business. Eight of the nine members of Eisenhower's cabinet were millionaire corporate executives. Three men -- Charles E. Wilson, Arthur Summerfield, and Douglas McKay -- had ties to General Motors, which prompted Adlai Stevenson to say, "The New Dealers have all left Washington to make way for the car dealers." Ike was a staunch opponent of deficit spending, and vetoed the following legislation: * * * * Two public housing measures Two anti-recession public works projects Anti-pollution legislation Area redevelopment proposal To be fair, Eisenhower's term did see a rise in Social Security coverage, a higher minimum wage, and expanded unemployment insurance coverage. Although he desired to balance the budget, there were four obstacles to Eisenhower's attempts to reduce federal spending: 1. Growing demand for military and foreign aid 2. Negative effects on economy when reductions were made 3. Unacceptable political costs As a result, the end of the Eisenhower administration saw the highest peacetime deficit to that time. It had grown from $266 billion in 1953 to $286 billion in 1959. The Call for an Active Presidency By 1959-1960, the final two years of Eisenhower's term, a great debate was brewing in American society about the present and future of the United States. This debate centered around two major focal points: 1) America's spiritual and cultural malaise and 2) Cold War politics. Many looked forward to the 1960 presidential election as the beginning of a new direction for America under new leadership. As it turned out, both candidates -- Republican Richard Nixon and Democrat John F. Kennedy -- were identified with McCarthyism and the politics of tranquility. The 1960 campaign Thanks to his experience in Congress and his eight years as Eisenhower's vice president, Nixon was highly qualified to be President, especially in the realm of foreign affairs. However, he had a reputation as a hatchet man and a redbaiter from his role in the Alger Hiss trial. When Ike had a heart attack in 1956 and people began to express apprehension that Nixon was next in the chain of command, the Republicans unveiled a "New Nixon." This "New Nixon," although slightly less menacing than the old version, still exemplified the hollow man of a homogenized society. On the other side of the aisle stood John F. Kennedy, who seemed to many like a Democratic incarnation of Nixon. Kennedy, then a senator from Massachusetts, had been the lone Democrat to support Joe McCarthy when the Senate voted to censure him. In another demonstration of questionable ethics, Kennedy plagiarized the book Profiles in Courage, merely rewriting and signing his name to a work which his research assistants had written for him. Practically since birth, JFK had been groomed to become President some day. His father, Joe Kennedy, although striking it rich in Hollywood, still felt shunned by elite society because his family was Irish Catholic. Religion did play a part in the campaign, if only briefly. Before Kennedy, no U.S. President had been Roman Catholic. The only other serious Catholic contender for the presidency was Al Smith, who lost to Herbert Hoover in 1928. JFK managed to defuse the Catholic issue when he won the Democratic presidential primary in West Virginia, a largely Protestant state. John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-1963) Kennedy won the election, but only by a popular margin of about 120,000. Once in office, Kennedy proposed his new plan for America, which he dubbed the "New Frontier." Overall, this New Frontier had three main points: 1. A more sophisticated sense of economics 2. An emphasis on social welfare programs 3. Cold War policies and the space program Specifically, Kennedy had eight goals in his New Frontier, most of which were defeated in Congress. 1. Increased federal aid for education. Defeated. 2. Medical care for the elderly. Defeated during the Kennedy administration, but eventually enacted as Medicare and Medicaid. 3. Increase in minimum wage. Passed. 4. Urban reforms. Modest success. 5. Civil rights. None. Despite the lingering myth that JFK was a strong proponent of civil rights, his administration saw no major civil rights legislation. It was actually brother Robert Kennedy, JFK's attorney general, who was passionately committed to civil rights. JFK, afraid of losing the always tenuous support of Southern Democrats, put civil rights on the back burner once he was in office. 6. End to poverty. No. 7. Major tax cuts. Defeated. 8. Cold War goals. Yes, Kennedy's term saw both increased expenditures on defense and money for the new space program. Kennedy proved to be a man of much rhetoric and little action. Frequently appearing on television to promote the New Frontier, Kennedy actually accomplished little in the way of legislation. To his credit, Kennedy did demonstrate growth in his understanding of economics. Having come to the White House as a fiscal conservative, he grew to understand the complexities of the economy. Kennedy and his advisors dubbed his economic plans a "New Economics," although they weren't much different from Keynesian economics. They advocated: 1. 2. 3. 4. Moderate increase in federal spending Trade Expansion Act Stabilize interest rates Major tax cuts Unfortunately, these ideas were received either lukewarmly or negatively in Congress and the American public. Many of Kennedy's economic ideas were eventually proven true, but only after his term in office, which was cut short on November 22, 1963. The assassination of John F. Kennedy caused a great many myths to spring up around the memory of the President. One myth regards Kennedy's alleged devotion to civil rights for black Americans.