basic elements of human economy

advertisement

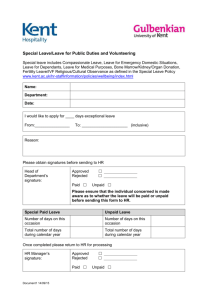

International Household & Family Research Conference 2002, Helsinki, Finland (Revised 2007) BASIC ELEMENTS OF HUMAN ECONOMY A SKETCH FOR A HOLISTIC PICTURE Preface 2 Introduction 2 1. The household - a core of human economy 3 1.1. The origin of the picture 1.2. The value of nonmarket, unpaid work 1.3. The breadwinners of the world? 3 6 9 2. The households as strongholds against globalization 12 2.1. Developing a new picture of national economy 2.2. Interplay between public and private 2.3. Turning a trap into an asset - a good life Utopia? 2.4. The household as a counterforce to market globalization 12 14 15 16 3. Cultivation economy - the interface between economy and ecology. 16 3.1. Cultivation versus industrial production. 3.2. Food or commodities? 17 19 4. Conclusion: The Triangle of Human Economy 21 References 23 Hilkka Pietilä, M.Sc. Independent researcher and writer affiliated to University of Helsinki, Christina Institute for Women Studies e-mail: hilkka.pietila@pp.inet.fi 2 BASIC ELEMENTS OF HUMAN ECONOMY A sketch for a holistic picture Preface Today, there is a pressing need for a new, more comprehensive and relevant perception of human economy as a whole in order to understand the prerequisites for sustainable livelihood for the whole of humanity and to be able to create a lifestyle which could provide a dignified quality of life for all people, with due respect to the ecological boundaries of the biosphere. The presupposition in this paper is that human economy is composed of three major, distinct components instead of one, monetized industrial economy, as usually taken for granted in mainstream economics. Those components are the household economy and the cultivation economy in addition to the industrial economy. In fact, households and cultivation have always existed, long before money and industry ever emerged, but they have remained invisible in the eyes of mainstream economists. It is the purpose of this paper to make all these three components visible and elaborate their background and characteristics, and to argue for the necessity of their inclusion. The ultimate aim is to challenge alternative and feminist economists into collaboration for the creation of a new theory of human economy and to expand the domain of economic inquiry accordingly. Hopefully, this paper would also prompt us to consider to what extent we would like to acquire more control over our livelihood and to decrease our dependency on factors beyond our control, such as the globalized free market with all its consequences, and to what extent this would be possible without putting at risk other important elements and needs in life. Introduction Human well-being consists of material and nonmaterial "goods", of monetized and nonmonetized production. The historical transition from the subsistence economy to monetarized economy has had many repercussions on basic conditions of human life, and particularly on the life of women. Not all of these effects have been positive, and neither have they all been understood and taken into account. Understanding the history and the composition of human economy more comprehensively may give us new visions and insights on how to solve the problems of living in a global economy of increasing scarcity. We in the North need visions for transition from a wasteful, consumerist market economy towards a more sustainable way of living. The concept of human economy is used in this paper to signify all work, production, actions and transactions needed to provide for the livelihood, welfare and survival of people and families, irrespective of whether they appear in statistics or are counted in 3 monetary terms. It implies also a basic understanding of the necessity to manage the human household in a sustainable way. The major blind spots in the prevailing economic thinking seem to be: - the household economy, which is used here for the nonmarket, unpaid work and production by a family or a group of people having a household together for the management of their daily life, irrespective of whether they are kindred or not; or even a group of small households living close enough to create a joint economic unit, and - the cultivation economy, i.e. the production based on the living potential of nature, which is the interface between economy and ecology, human culture facing the ecological laws. These constituents of human economy are either misconceived or ignored. The doctrines of economics seem to be derived from physics and mathematics, the sciences dealing with non-living objects and material in the universe (Mäki, 1991; Vorlaeten, 1995). Thus, economics does not take account of biology, the science of living creatures and processes in nature; and that explains why economists seem to be blind to the logic of living nature. Both of these economies are very basic from the point of view of a sustainable way of living, and thus for human survival and people's ability to control their own lives. A particular feature of the households is the extent and significance of nonmarket labour of people without pay for direct production of welfare, and thus as an essential contribution for human livelihood. A particularity of the cultivation economy is its profoundly unique nature by being based on living potential of nature. Human beings are not considered in this paper merely as part of living nature - as many ecologists do - but as the only rational and responsible species in the universe, which is accountable for its behaviour and its management of the only planet suitable for its existence and welfare. Neither does this paper take a human being as mere "Homo Economicus", whose only motivation is the pursuit of self-interest and maximized satisfaction of needs on lowest possible costs and efforts. 1. The household - a core of human economy The household as a basic economic unit in a society lends itself easily to use as a new angle from which to look at the economic process as a whole. For all human purposes, the household is the primary economy, which all other economic functions should serve as auxiliaries. If we start looking at production, trade and economic activities of any kind from the household point of view, the whole picture will change. 1.1. The origin of the picture In the course of history, most societies have at some stage of social evolution been agrarian societies consisting primarily of fairly self-sustaining farming families. Such families had their fate in their own hands for the good and the bad, i.e. they had much 4 more self-reliance and control of their livelihood - though at a very modest standard of living - than people living in the affluent, consumerist society. The basic structure of the society at that stage is the often quite extended private family, which provides for most of the basic needs of the family members: for food, clothing, shelter, caring, entertainment etc. On a modest level, the family is a fairly autonomous unit, depending only on the provisions of nature and the capabilities of its members. In spite of the often very patriarchal nature of traditional agrarian families, women had a central role in this kind of society because of their vital contributions to the livelihood of the family. Since only women knew certain essential tasks, this gave them a leverage of power in the society, where the services and goods could not be bought on the market. Thus the gender-based distribution of labour into male and female tasks does not necessarily imply inequality, as so often maintained in the feminist debate. In the process of so-called modernization, industrialization, monetization, commercialization of the society, many traditional functions are transferred outside the family. Making of furniture and clothing, growing of food, child and health care, training and education, even entertaining, have been transferred outside the family and monetized. They have become either public services, provided by the society, or commodities purchased on the market. A Swedish researcher, Ulla Olin, analysed this process profoundly in her paper prepared for a seminar on women and development, just before the first UN World Conference on Women in Mexico City, 1975 (Olin, 1975). She considers the family as a general model of human social organization and thus also of a society at large. Since an emerging state formation increasingly takes over the functions earlier performed by the family, she suggests terming the nation state as a symbolic family or public family. This fits the Nordic welfare states in particular. (Figure 1.) We have to study also the interplay between private and public families. In traditional cultures, the societal structure outside private families was fairly thin. In the process of modernization, the structures of industrial production, trade, administration, public services, security and education grew stronger and increasingly powerful. In this process, the tasks and skills of people became dispensable. It became possible to substitute almost everything with industrial products. Nobody is indispensable any more in the economic sense. This was the beginning of commercialization of life and ultimately even human relations. For women, this development has naturally given new knowledge, tools and gadgets to make life easier, but it has been detrimental, too. The skills and tasks which used to be particularly women’s strengths have become dispensable and thereby their inherited leverage has virtually vanished. In the course of this process, women were the last to remain in the private sphere, when men went to war, work and politics, children were sent to school, the sick were taken to hospital, and the aged were put into old people's homes. Thus women were also the last to enter the labour markets. That is one of reasons why they got the most monotonous and mechanical jobs, or those requiring manual skills and patience. Men were not able or willing to do these kinds of jobs - therefore they are also poorly paid even today (Friberg, 1983). 5 Figure 1. The Origin of the Picture In human history after the transition from the gathering economy to the cultivation economy the extended farming family has been a basic unit of livelihood for long periods. Along the time the people’s skills and means developed to enable qualitatively better satisfaction of their basic needs. This kind of “a house-hold” (note: holding the house/farm) was fairly independent and selfreliant economic unit at the modest level. The livelihood was based on the quality and accessibility of natural resources and skills and assiduity of the people living together. In the course of time various kinds of production and trade, independent artisania, exchange of goods and services, public institutions and administration were emerging around the farming families. The public society and economy was in the making. A means of exchange came into the picture, and people started to buy and sell goods and services. The people and knowhow, i.e. the labour and skills, started to move from the private families to the public market. The construction of monetarized economy and public structures took place. Gradually the public society emerged around the private households and the transition process of functions and people from the private to the public has continued ever since. Women were the last ones remaining in the private sphere. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The process described above imply that - in the course of history - the public family, production, politics, culture and organization outside the private family, was designed, planned and built up exclusively by men, who possessed neither the particular gifts nor the experience which women had acquired over centuries of managing the private family and nurturing its members. Ulla Olin considers this long-term imbalance between the male and the female rate of influence in planning and conduct of modern industrial societies to be the virtual source of most of the social, economic, human and international problems which we face today 6 1.2. The value of nonmarket, unpaid work Seeing the process of emergence of the market economy through gender lenses helps us to understand better the lopsided state of industrial societies today, and the exclusion of and discrimination against women in these societies. It also gives an insight into the dynamics which still prevail between the home-based subsistence production of goods and services, on the one hand, and the public services and market on the other. It is obvious that the amount of unpaid work is significant in the developing societies, but what is the amount and value of non-market production of goods and services in the industrialized countries? Even though industrial production and public services have taken over a major part of this, a lot of work is still done in homes and families. A lot of surveys has been made in different countries concerning the time and amount of unpaid work in the households. And plenty of work is done for developing appropriate methods for measurement and valuing of the work and production done within the households outside the monetary economy and market ( INSTRAW, 1995). The usual pattern of approaching this issue is that first the amount of work done in the households is measured in time, hours and minutes, the so called time-use survey being done. Even this is a complicated matter, since the housework usually implies several jobs being done parallel, for example tending to children while cooking and laying the table or ironing and mending the cloths. Is the issue just counting hours spent or counting the hours per function as to how many hours for tending to children and how many hours for cooking and laying the table? For the statistics the value of work has to be calculated in money. This is even more problematic. What is the time wage or market price of the work which has an incalculable human value - like taking care of lively and dear children - and which requires a command a great number of skills? Or the work which is composed of low paid and highly paid components like washing the cloths requiring simple washing work plus the knowledge of the technician for managing the washing machine and the chemist knowing the composition and effect of the detergent? The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD has done a lot of work for creating the data sources and methods for measurement of unpaid, non-market household work and production in the OECD countries(OECD, 1995). The main categories of methods they have elaborated are the following: - the “opportunity cost” method, which is based on the potential salary, what is the wage opportunity lost by the one who does unwaged work, for example caring for her children or parents or doing subsistence farming instead of doing a paid job; - the "global substitute" method, whereby a general housekeeper's wage rate on the market is taken as a substitute value for all unpaid housework, and which rests on the assumption that housework does not require any particular qualifications; - the "specialist substitute" (also called “the replacement cost”) method, which relates various types of household tasks to the wage levels for the type of work performed by professionals such as cooks, nurses, gardeners etc. 7 All these ways of measurement are applying so called input-based method, because they measure the household production through the inputs to the process, in particular the working hours. The UN International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women, INSTRAW, suggests a method not mentioned in the study above, such as - the “output-based evaluation”, which implies the valuation of the non-market production in terms of the market value of the outputs produced, whereby the products and services produced in the household are assigned a value equivalent to the price of similar market goods and services (such as the meals served in the restaurant, the cleaning performed by a professional firm, etc). Output-based evaluation method does not require time-use data, but the data about the amount of goods and services produced in the households and their values in the market. It is obvious that the estimates of the value of household production depend, on the method used. A OECD researcher Ann Chadeau considers the specialist substitute method to be the most plausible and at the same time feasible approach for valuing the non-market work and production in the households (Chadeau, 1992). INSTRAW deplores, that in the past there have been very few attempts to estimate the value of household output, while it is technically possible and less time-consuming than the surveys based on time-use measurement (INSTRAW 1995). The thorough time-use surveys on unpaid housework has been made in Finland in 1980 (Housework Study, 1981),1990 (Vihavainen, 1995) and the latest in 2000 (Niemi&Pääkkönen, 2001). The monetary value has been assessed on the two earlier ones, the survey in 2000 gives so far only the time-use. In 1980 the monetary value was calculated according to the then current salary of municipal home helpers ie using so called “global substitute” method. In the 1990 survey the monetary value was counted in two ways, both using the global substitute method as in 1980 and for comparison also by using the average wages on the labour market for all employees. Due to somewhat different procedures, these surveys in ten years apart are not fully comparable, but some conclusions can be drawn by comparing their results in terms of both time and value of work. The time spent in unpaid labour in average Finnish families in 1980 was 6 hours 40 min. a day. The survey included all the unpaid work in the households irrespective, whether it was done by women, men or children, but the gender distribution of work was also assessed: the women’s share was 4 hours 48 min., and men’s almost 2 hours, then the women's share was in average about 70 %. The total monetary value of the unpaid labour in households in Finland in 1980 was about 42 % of the GNP (Table 1). In the 1990 calculations the average amount of unpaid work per household was 6 hours 16 min. per day, which is only 26 minutes less than in 1980. The share of women was 63 % , i.e. almost 4 hours a day and by men 2 hours 20 min. a day. When assessed according to the current salary of municipal home helpers, it made FIM 232 000 million. Using the average wages on the labour market for all employees as the yardstick, it reached about 300 000 million FIM. Compared with the GNP the monetary value of unpaid work in 1990 was 45-60 % depending on the method of calculation. 8 Concerning the possibilities for remuneration of the unpaid labour it might be useful to compare these calculations with the state budgets of the corresponding years. For Finland the sum total of state budget in 1880 was FIM 50 000 million and the value of unpaid work was - even according to very low yardstick – FIM 80 000 million. The sum total of the Finnish state budget in 1990 was FIM 140 000 million and the value of unpaid work was FIM 232 000 – 300 000 million. Thus the non-market household production was worth more than one-and-a half to two times the amount of the state budget in that year, depending on the method used in assessment. Table 1. Gender distribution of unpaid labour in households in Finland, 1980, 1990 and 2000. Women Men 1980 1990 2000 Hours/minutes/day 4.48 3.56 3.47 1.54 2.20 2.27 6.42 6.16 6.14 The distribution of unpaid work between men and women varies a lot between the households as well as between the countries. Then an interesting aspect in the Finnish surveys is, whether the distribution of unpaid work between men and women had changed during the years. We can now compare the figures of three time-use surveys with ten years in between. It levelled out a little between 1980 and 1990, men doing a little more and women a little less in 1990 than in 1980, albeit this difference may also be partly due to the slightly different methods used. Between 1990 and 2000 hardly any change has taken place. Even the total amount of unpaid work in the households has not changed. "Whatever valuation method is used, the value of unpaid housework is substantial in relation to GDP. Non-market household production is an important component of household income, consumption and welfare," concludes Ann Chadeau in her paper (1992). In Finnish calculations for both 1980 and 1990, the value of unpaid housework was between 42 - 60 % of GDP, depending on the method of estimation. This is comparable with the results from various countries shifting between 30 - 60 % of GDP (INSTRAW; 1995). Thus the conventional SNA statistics give a grossly distorted picture of the magnitude, composition and trends of productive activities in each country. "For the last fifty years national income statistics have been widely used for monitoring economic developments, for designing economic and social policies and for evaluating the outcomes of those policies. Had household production been included in the system of macro-economic accounts, governments would have had quite a different picture of economic development and may well have implemented quite different economic and social policies," says Ann Chadeau. The women's movement has insistently demanded for decades that the value of women's unpaid work should be counted as part of the national income in each country and included in the System of National Accounts. 9 In Finland the first professional woman economist Laura Harmaja argued in her writings and public debates 1920s for the inclusion of the household production into the system of national accounts. In her extensive work on this issue she presented already well founded estimates about the amount and value of this work proving that the sum total of this work would be much higher than the production of state, municipalities and consumer cooperatives altogether at that time. Her main work Kotitalous kansantalouden osana (‘A Household as Part of National Economy’) was published in 1946 (Heinonen, 1996). In recent years the most prominent proponent for this issue has been Marilyn Waring, whose book If Women Counted. A New Feminist Economics became a classic right after its publishing 1988. Her criticism focuses particularly on the prevailing international system of national accounts and contributed undoubtedly to the revision of the SNA by the UN in 1993 (Waring, 1988). The women’s movement as well as feminist economists have also criticized the methods so far being used in these kind of calculations. Calculating the monetary value of the household work by comparison to the wages which women could earn at the labour market (where the women’s wages are lower than men’s in all countries) or to the prices of the same type of work performed by a professional ( which most likely will also be a low paid woman), both methods would perpetuate the pattern of all labour market, where women are low paid in general. This criticism is particularly apt to using as the measurement the general housekeeper’s or municipal home helpers’ wages, which are very low rate work in all countries, indeed. The output-based evaluation method suggested by INSTRAW do avoid this problem, but creates an other problem of comparability, because it obviously gives different values in different countries related to the level of prices and salaries at the market in respective countries. The other method, which does not fall into this trap, is to take the average of all wages in the labour market as the yardstick as it was made in the Finnish study in 1990 for comparison. It makes some justice also to the fact that the housework - more than practically any other job - demands the multitude of skills from cooking, cleaning, child care to planning, administration and management, economic calculation as well as physical and mental health care, design and composition of the housing, gardens and surrounding, tending to social, economic and cultural relationships, etc. 1.3. The breadwinners of the world? The UNDP/Human Development Report 1995 gives even a global estimate of the amount of women's unpaid labour. The main theme of the 1995 report is the failure of statistics in general to do justice to women in reporting on their economic contributions, paid and unpaid. "If more human activities were seen as market transactions at the prevailing wages, they would yield gigantically large monetary valuations. A rough order of magnitude comes to a staggering 16 trillion (dollars) - or (if added, it would make a total of) about 70 % more than the officially estimated 23 trillion of global output. Of this 16 trillion, 11 trillion is the non-monetized, invisible contribution of women." "Of the total burden of work, women carry on average 53 % in developing countries and 51% in industrial countries." (See Figure 2) Out of the total time of women's work, 1/3 is 10 paid and 2/3 unpaid. For men it is just the reverse: 3/4 of their working time is paid and only 1/4 is unpaid. "If women's unpaid work were properly valued, it is quite possible that women would emerge in most societies as the major breadwinners," concludes the HD report (UNDP, 1995). Due to the long cooperation with INSTRAW (the UN International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women) the Statistical Division of the UN took a stand on whether household production should be included in the SNA (System of National Accounts, 1993). The 1993 SNA recommendation entails two different categories of national accounts. Its hard core contains the traditional national accounts, which are called the central framework. This is surrounded by looser satellite accounts, which are separate from but consistent with the core national accounts and can measure areas of interest that are difficult to describe within the central framework. (Ruuskanen, 1995). In principle, the SNA approves the notion that the goods and services produced at home are part of production in the widest sense of the term. Nonetheless, the problem seems to be, what should be counted as production? The production of goods and services at home for the needs of the family members does not fit into the definitions which have been used until now. Therefore, for the purposes of the central framework, the SNA has now chosen to use the definition that production includes the goods but not the services produced in the household for members of the same household. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Figure 2. Recognizing women's contribution Of the total work burden, women carry more than half. Three-fourths of men's work is in paid market activities, but only one-third of women's work. Men receive the lion's share of the income and recognition, while most of the women's work remains unpaid, unrecognized and undervalued. Source: UNDP, Human Development Report 1995. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------This may make the calculation of the value of unpaid household work even more complicated, since it has to distinguish the work for goods from the work for services. Even the definition of goods seems to be fairly arbitrary. Growing of vegetables, production of wine or cheese, and making of clothes are counted in the SNA; but preparing meals, washing the dishes and clothes, cleaning the house, or caring for children and the elderly should go into the satellite accounts (SNA, 1993). Still, even these functions would be counted in the SNA if they were produced by paid domestic servants. In the monograph “Measurement and Valuation of Unpaid Contribution: Accounting through Time and Output” INSTRAW (1995) recommends that: 11 - - a framework defining activity classification for SNA and satellite activities should be established; an internationally acceptable SNA Satellite Household Sector Account should be defined; the Household Satellite Account should include all activities associated with the maintenance and upkeep of households and families, all activities related to gaining an education, and volunteering; an output-based approach to valuing non-market production be developed; steps to be taken to develop accurate and efficient time-use data collection approaches; data capture for the household satellite account should be carefully planned and undertaken using a range of instruments and approaches. According to the INSTRAW monograph: “Benefits from the development of a household satellite account and the generation of data to service that account would be far-reaching. Such an effort would facilitate implementation of the 1993 SNA measurement requirements, provide time-use data for formulating policies on women, and facilitate increasing literacy, the assessment of the importance of the transportation sector, the accounting for time lost due to sickness, the measurement of children’s work input and the human capital building process, the measurement of voluntary community services, the measurement of social and economic change, and informal sector measurement.” The INSTRAW monograph was published before the IV UN World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 in order to prompt the recommendation for the support of the SNA Satellite Account on Household production to be adopted. An extensive chapter on Women and Economy was included in the Platform for Action adopted in Beijing (UN/WCW, 1995). It elaborates thoroughly the triple role of women in economy production, caring and community management - and the impact of both national and transnational economic policies on women. The Platform strongly urges the governments and UN Agencies to make sure that the SNA recommendation concerning satellite accounts of women's unpaid work and production will be implemented. This urge by the Beijing PFA prompted the European Union to make an invitation in 1996 to the Statistical Offices of the member states to submit tenders for developing a common concept of a comparable satellite system in each member state and a common one for the European Union for making visible the unpaid work done in the EU countries. The Statistics Finland won the tender and it has provided to the Eurostat a proposal for a European system of satellite accounts attached to the present System of National Accounts. However, the proposal is just the first step in Europe. It will take time and work to bring this process forward within the EU system until it will become “a harmonized common satellite system on household production for the European Union” adopted by the Commission and given as a binding directive to the member states. So far the progress has been very slow and it is not yet foreseen, when the new system in Europe might be in use. 2. The households as strongholds against globalization In the early 1980s prof. Kyösti Pulliainen and myself made a hypotheses, that revival of the self-reliant, non-monetary local and household-based production of goods and 12 services makes economic growth unnecessary in small industrialized countries like Finland, without necessarily jeopardizing the quality of life. Our aim was to find ways of reducing the need for economic growth in a well-off industrialized country with a view to decreasing international disparity and exploitation of natural resources (Pulliainen & Pietilä, 1983). 2.1. Developing a new picture of national economy On the basis of the 1980 assessment of the unpaid work in the households in Finland we made an effort to rectify the picture of national economy in such a way that it will include the nonmonetary, home-based economy as well. We perceived the national economy being composed of three concentric circles. That time this idea of the tripartite picture of national economy was suggested also for instance by Lars Ingelstam and Mats Friberg in Sweden (Ingelstam, 1980; Friberg, 1985). According to our hypotheses the national economy consists of: - the free economy composed of the unpaid, nonmarket work and production in the households. It is called ‘free economy’ since it consists of the work that people do ‘freely’ without pay for the well-being of their families and pleasure; - the protected sector of production and work for the home market as well as public services (such as agriculture and food production, construction of houses and infrastructure, administration, schools, health, transport and communication etc.); - the fettered economy, the production of goods for export and substitution of import, which is fettered to the world market, and thus the terms of this sector, the prices, competitiveness, demand etc. are determined by the international market.(Figure 3.) In Figure 3 we placed the free economy in the middle, since it is the basis of the human economy. That time the second circle, domestic sector was protected and guided by legislation and official policies in the Nordic countries, and thus the prices, wages and other terms in this sector were determined domestically without too much pressure from outside. The fettered economy is linked with the international market and the bigger this economy grows the more dependent the national economy becomes on factors outside the sovereignty of the country. In 1980 the fettered economy in Finland accounted only for 10 % of the total working hours and 19 % of the value of total production. Ten years later in 1990 the proportions of fettered sector had changed surprisingly little as indicated in the table under Figure 3. 2.2. Interplay between public and private The dynamics and interplay between the public family and the private family, i.e. the visible and invisible economies, is easy to be realized in the Figure 3. Earlier in this paper we discussed the amount and importance of the unpaid labour and production in the households and neighborhoods. In economic calculations such essential functions in the society as child and health care, cooking and cleaning, education and training, etc. are not counted as contributions (inputs!) to the economy as long as they are performed within families. But as soon as they are transferred from the private family to the "public family" and performed by private or public institutions (schools, hospitals, business), they cost money, they imply large investments and expenses to both individuals and society. Then they are outputs and counted in the GNP. 13 Figure 3. Another Picture of the National Economy The core of the human economy, the household and community economy has been included into this new picture of the National Economy (by Pietilä & Pulliainen). It is in the middle of the picture, because everything else has been build around it within the course of history of the human economy. It is the centre of human economy, whenever the picture is seen from the perspective of families and individuals. We counted, how much will the GNP be in Finland in 1980 and 1990, if also the non-monetized work and production was included. The figures below are then counted as proportions of this “greater” GNP. A. The “free economy” B. The protected sector C. The fettered sector 1980 Time 54 % 36 % 10 % Money 35 % 46 % 19 % 1990 Time Money 48 % 37,5 % 40 % 49,5 % 12 % 13,0 % The proportions of different sectors have changed surprisingly little in ten years 1980-1990. In 1992-1995 “the free economy” was likely much bigger, since about 14-15 % of the labour force was unemployed and then the non-market work in the families may have increased significantly when people were substituting their declining incomes with increasing work in the households. The surveys indicated that the standard of living (i.e. the quality of life) in the families did not decline in proportion with the decline of purchasing power of people. The membership of Finland in the European Union from the beginning of 1995 has, however, changed the whole picture of the Finnish national economy crucially, since the protective measures and customs have been eliminated from the internal borders between the EU countries letting then the fettering effects of international markets enter heavily into the national economy. The fact is, however, that when these functions are performed within families or otherwise by voluntary work they cost a lot of time and work, and when produced in public sphere, they cost money. A major part of economic growth in the past has consisted of the functions that have been transferred from the private family to the public one, from the non-monetary sector to the monetary one and thus been made visible. 14 From women's point of view this discussion is very important. The non-monetary economy in the industrialized countries is still primarily a female economy. Its invisibility is a supreme manifestation of women's invisibility in the society at large. The family economy is in the hands of women even in its monetized form, the consumption of marketed goods and services, because purchasing decisions are made primarily by women. The economic policies of the European Central Bank requires the governments to liberalize the economy, to cut public expenses and lower the taxes, therefore they cut resources from the public institutions, which imply reduction of the number of public employees. In fact these measures imply pushing the services back to the private sphere and "disemploying" women, in other words women are pushed back home to produce these services for their families without pay. After the recession in early 1990s and accession of Finland into the European Union in 1995 the government has applied increasingly neo-liberal economic policies and the hard core export industry has been doing better than ever. Still the rate of unemployment remains high. And the more unemployment the more unpaid work is done in the families and households in order to retain the quality of life as well as possible. In reality the greatest flexibility in the labour market appears in the households – by force of necessity. In the times of recession and structural adjustment, due to lack of paid jobs, declining incomes and dismantling of public services, people have to manage their daily life by doing more themselves at home. It looks as if even the governments were relying on this potential of the families and women to expand their caring capacity in proportion to cuts of public spending. On the other hand a rapidly strengthening trend now is the privatization of public services and enterprises like railways, postal services, oil and fertilizer industry, and even schools and hospitals, which in Finland have been public services forever. Also the unemployed people are persuaded to start their own enterprises. They are provided with training and retraining for that purpose and the access to credits is made easier. All life and society is about being made to a market place. This process follows the dogma of industrial society to believe, that economic progress consists of a continual shift of labour and skills from household-based production to the commodity-based consumption, as presented by Italian economist Mario Cogoy (1995). He says that the extreme form of market utopia consists of two ideas: on one hand people are supposed to acquire professional competence only on one single field, where they will then earn money enough in order to buy everything else in life from the market. On the other hand this will then imply total abolition of work and skills in the families, in the private life of people, since all labour and skills are absorbed into the market. Time outside the economic system is reduced to pure unskilled leisure-time. This way also the living households would cease to exist and the home remains only as a place to sleep. If the market forces are allowed to pursue these aims to the ultimate, they will render people totally dependent on the market and make them helpless and powerless pawns in their society. This would legitimate the continuity of the market forever and reduce people only to means of consumption and production, to fuel for keeping the system running. This process will annihilate the human dignity of everybody. 15 2.3. Turning the trap into an asset – a good life Utopia? Already in the beginning of 1980s the founder of futurology, Robert Jungk, made the point that “people out of work are, in certain way in a privileged position because they are no longer chained to the capitalist production machine. They have more time, they can think and act in ways which may be beneficial for society, if they have enough motivation.” (Jungk, 1983) This thought of Robert Jungk gives hope that we could – and we should – stop the rat race and turn around the wheel, while the advancing technology is rendering increasing number of people jobless, and the market is supplying cheap mass-produced goods and gadgets for all possible purposes thus making our skills and capabilities useless. The question is, whether we could transform this situation into an asset instead of a trap? The lack of regular job will allow us to command more of our time, and the declining income could become an incentive for us to make more use of our skills, knowledge and experience. This situation could, in fact, guide us to take more control on our lives? How would it feel like, if we start making our own plans for our household economy and decide to do more at home in order to decrease our dependence on the money-income and supply of the markets? Would this become a strategy to use power from below, to give us power to influence the economy around us? In this kind of a economic transition the household will again become an asset in the hands of people. When people realize that the more of necessary goods and services they are able to produce by themselves, the less they are dependent on the market, both on labour market and the market of goods and services. Thus they would gain capability to command again their own everyday life. But increasing voluntarily work at home will only increase the workload of women? We should not allow it to become so. Therefore it is necessary to equalize the distribution of labour between women and men, girls and boys, in the households. Even for the sake of men it would be necessary to design a new division of labour at home. It will give them a meaningful and rewarding new role in the family, While they no more can be breadwinners they could become direct supporters of their families in practice. In the economically well-off countries the skills needed in various chores of the household have been deteriorating along with the mechanization and commercialization of our lives. However, the household can still be a place to gain and train practical skills for everyday life, if we so wish. And the household tasks provide ample opportunities for work, where one can utilize “the trinity of human skills”, hands, head and heart parallel. Such a work stimulates one’s creativity and facilitates personal evolution and integrity contrary to many highly specialized professions. Two things go always hand in hand: If we decide to consume as little as possible and buy from the market as little as possible, our need of money-income will be much less and we would be much less dependent on paid jobs. A decisive asset for making these changes possible is the multiplicity of practical skills, they are much more important than money. The more practical skills one master, the more choices she/he has in everyday life and the more independent in life she/he would become. 16 2.3. The household as the counterforce to market globalization As it was pointed out already in the beginning of this paper, the household economy (both monetary and non-monetary) is, from the human point of view, the primary economy. It works directly for the satisfaction of essential human needs - material, social and cultural needs. The household also produces “goods” that are not available in the market and cannot be purchased for money, such as the feeling of being somebody, closeness, encouragement, recognition and meaning in life. All this is realized in connection with living and doing things together; cooking, eating, cleaning, playing, watching TV, sleeping, sharing joy and sorrow, and transferring human traditions. In this sphere, every man, woman and child is a subject, recognized as a person; everyone is indispensable. If the human maintenance - mental and physical - and the nurturance of human beings are not taken care of, no other economy is possible. Thus the household is basic not only for the economy, but for the whole society, for the survival of the human species. Therefore the picture of the human economy should be turned the right side up; the industrial and commercial economy should be seen as auxiliary, serving the needs of families and individuals instead of using them as means of production and consumption. This turn around will definitely not be made by the market economy, neither it will be done by our democratic governments any more in today’s world. In the globalizing world we have to do it by ourselves, to take the power back in our own hands to command our own lives. 3. Cultivation economy - the interface between economy and ecology. The most fatal shortcoming of prevailing economics as science is that it does not distinguish the cultivation economy from the industrial production, from extraction and manufacturing. As it was stated in the beginning of this paper, the doctrines of economics seem to be derived from physics and mathematics, and therefore it does not recognize the science of life, biology. The survival of human species, however, as the most complex life form in the universe depends ultimately and decisively on living nature, not on minerals and fossils. "The more complex forms of life ... are radically dependent on all the stages of life that go before them and that continue to underlie their own existence. The plant can happily carry out its processes of photosynthesis without human beings, but we cannot exist without the photosynthesis of the plants. Human beings cannot live without the whole ecological community that supports and makes possible our existence" (Radford Ruether, 1983). Many indigenous traditions suggest that women invented agriculture and animal husbandry at “the dawn of history when their men were out hunting”. Around the dwellings they started to cultivate the plants, which had been found tasty and edible, and they tamed the orphaned cubs of wild animals by breast feeding them. Thus they helped to provide food for the families even when men did not succeed in fishing and hunting. This indicates two different ways of relating with the nature; fishing and hunting, 17 exploitation of nature, taking without giving; cultivating and feeding, nurturing when utilizing, mutually giving and receiving (Pietilä, 1990 a & b). During the long agrarian history of the humanity the principle of ‘nurturing when utilizing’ was the most effective way of providing livelihood by men and women alike. Nurturing the animals was primarily the women’s work and cultivating the crops and other plants the male job. Until this century - in Finland still in 1920s and 1930s - the agriculture was fairly ecological due to mere necessity, lack of industrially produced inputs, such as energy, fertilizers, pesticides, advanced machinery, etc. 3.1. Cultivation versus industrial production. The cultivation economy produces basic goods in cooperation with living nature, i.e. the ecological systems. Agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishing and all indigenous livelihoods belong to this type of economy, which operates with plants, trees, animals and micro-organisms (e.g. microbes, yeasts and Rhizobium), the renewable resources of nature. Soil itself is the ecosystem full of life. Cultivation is in fact the interface between human economy and ecology, interaction between human beings and nature, where we should profoundly understand the terms of ecology, and take them carefully into consideration. It is crucial for the fate of humanity that we understand the particular nature and terms of this economy and conduct our handling with it accordingly. We should learn to care the living creatures, plants and animals on their terms, while utilizing them. Their living processes and well-being is the foundation of sustainable wealth and health of human species, too. A successful and harmonious interplay between human economy and economy of nature, the ecology, is the essential prerequisite for sustainable cultivation. Figures 4, A and B are an attempt at illustrating and comparing the basic differences of cultivation and industrial economies. The main characteristics of these distinct spheres of production are listed under the pictures, where it is easy to realize how profoundly different systems they are. Cultivation economy can also be called a living economy, because it is regenerating and sustainable, if the ecological terms are taken into consideration. The productivity and output of this production can be predicted and controlled only in definite limits, since - for instance - the amount of rain and sunshine, warmth and frost cannot be predicted and directed by human means. The nature has programmed the timing and rhythm of procreation and growth, too. The length and timing of production seasons are very different according to the latitude and geographic location of the countries and regions. Therefore the preconditions of production are extremely different in different parts of the globe. In Finland we can harvest only once a year, irrespective how hard we work or what methods we use. In Southern Europe the farmers can cultivate all year round and get several harvests a year. Industrial production can be called extraction economy or dead economy, because it was originally based on manufacturing of nonrenewable, non-living natural resources minerals and fossils - which are extracted from the earth. Today it processes also raw materials produced by cultivation economy, like wood, crops, meat, coffee, cotton etc. 18 Figure 4. An Illustration and Comparison of the Cultivation Economy and Industrial Production. (Pietilä, 1991) 19 The industrial economy is not very dependent on the terms of living nature, thus its productivity and efficiency can be improved as long as the raw materials are available. Its driving force is profitability. Economics as science is based on logic of industrial production, extraction and manufacturing of 'dead elements', nonrenewable energy and resources. When this logic is applied to the cultivation economy, the same demands of efficiency and productivity imposed on agriculture and husbandry as on industry, the system is bound to run into difficulties. Nevertheless, national and international economies have been run this way for as long as any intentional economic policies have been exercised. This misperception and mishandling of cultivation economy is the reason why agriculture has become such a problem both in national and world economy. This is also the reason why no solution has been found for the food problems of the humanity. And now when we are reaching the limits of the arable potential of the planet, these problems are rapidly becoming fatal. 3.2. Food or commodities? Trade has been considered to be mutually benefiting and profitable exchange between the partners with resources and capabilities. Competing with each other through trade the countries would also optimize their capabilities and the profitable exchange would benefit everybody. This goes as long as it is an issue only of competitiveness on productive skills and competence of people, and productivity and effectiveness of technical machinery. But it is absurd to apply the demand of international competitiveness on agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing and forestry, while natural conditions vary enormously from place to place on the earth's surface. The human competence does not hold good for adjusting the length of winter or the warmth of summer to the needs of competitiveness and even the breeding of more productive animals and seeds meet very definite limits. . Mother Nature is not a negotiating partner in the World Trade Organization, her terms are unnegotiable. The existing cultivation economies - both the basic production in developing countries and the agriculture of industrialized countries - are in unsurmountable trouble. Developing countries have fallen into enormous debts and regression. Agriculture in industrialized countries, in spite of the application of the most advanced technology and significant subsidies, creates constantly growing burdens for the national economies and is about to collapse under the burden and effects of insane cultivation practices. The problems of agriculture seem to constitute even a major reason for rapid migration from rural areas around the world, and thus the unmanageable growth of slums and urban problems. Finally the consequences fall upon the environment and destroy the foundation of cultivation economy and human economy as a whole. In free trade, agricultural products are treated as if they were equivalent to minerals and fossils or industrial products. The trade does not recognize the nutritional value as a particular quality; the food products are dumped into the same category as pulp and paper, tobacco and coffee. Hence, people's basic needs in many countries, have been 20 set at risk to increase export income by producing for instance tobacco and drugs instead of food. In 1974 a program for the New International Economic Order was unanimously adopted in the United Nations. It was a program for regulation of international trade for the benefits of developing countries. But it was never implemented due to the manoeuvring of the multinational corporate power already that time.(UN/GA, 1974.) For the purposes of getting hold on the world food problems there should be rules for trade, whereby the commodities were handled differently according to their importance vis-à-vis the basic human needs. Thus they should be differentiated e.g. into the following categories: 1) Food and feed products; grain, rice, milk and milk products, fruits, meat, groundnuts, soya, maize, etc. 2) Raw materials for industry; timber, cotton, rubber, jute, wool, etc. 3) Luxuries, primarily for Northern market; coffee, tea, tobacco, cocoa, sugar, etc. From the human basic needs point of view, these categories vary drastically in importance. If food production were a universal priority, as it should be, food problems would have been solved a long time ago. However, since priorities are defined only according to the commercial value of products, and to the rules of supply and demand, the world's food problems prevail. Meaningful priorities and prices do not coincide, since the market mechanisms are responsive only to demand and not to the poor people's hunger. Particular attention should be focused on the third category, the products of which take huge areas of the best arable land but are for no-one's basic needs, neither are they important raw materials for any necessary manufacturing. The rules of free trade may be well applicable to these goods, the law of the supply and demand might well adjust their prices at the appropriate level for those, who want and can afford to buy them. (Pietilä, 1991). In any case there should be applied appropriate regulations within countries as well as internationally to assure the adequate production of goods meeting basic needs. For instance, food should not in principle be an ordinary commodity at all, but an utility secured for everyone by the states and the international community, it should be cheap and easily available to all. This is approximately what a nutritional perspective on trade and an establishment of a world food security system would imply. The food production should be protected in each country according to the climatic conditions of the country concerned. This will be a must in near future if we want to save viable agriculture, animal husbandry and forestry in various parts of the globe, and feed the increasing population. The food self-sufficiency should be an ultimate goal and policy where ever the natural conditions are realistically feasible. (For example in the Nordic countries, where people have developed during the centuries the skills and knowledge, 21 how to provide the necessities for the inhabitants in spite of only one short cultivation season!) Ultimately, the terms of survival for cultivation economy are the terms of survival for all of us, the whole humanity. They are dictated by living nature. The cultivation should be understood as an authentically different component of human economy and handled with due regard to its particular nature. The farmers and other “cultivators” should be given such terms which will enable them to apply ecologically sustainable means and methods in their production. 4. Conclusion: The Triangle of Human Economy This paper is written primarily with the economy and lifestyle of affluent, post-industrial, countries in mind. It is exactly these countries which are, today, the ones hosting the transnational corporations and supporting their policies. Hence we can claim accountability from them, directly and indirectly, for the proceedings of today’s global economy. The considerations in this paper about limiting the economic growth naturally apply to the rich countries. These thoughts can be taken as the basis for criticism against the policies and actions of the rich industrial countries and as suggestions for change which is seriously needed particularly in the North. The present process of the economic globalization makes these issues even more pertinent. How can the local societies and people maintain the space for their efforts towards sustainable and self-reliant livelihoods? According to the Canadian feminist ecological economist Patricia Perkins, the local economies grow in response to economic globalization and global ecological realities. They are destined to play an important role in many peoples lives irrespective of whether they represent an accommodation to the global economy or an alternative to it. “Local terrain is extremely important, not just because it is ‘close to home’, but also because community-based economic alternatives and resistance to centralized economic control represent a fundamental challenge to the juggernaut of globalization” (Perkins, 1998). The more self-reliant and sustainable livelihood people can develop locally the more powerful they will be also to create political pressure on their governments to resist the globalized corporate power. Suggestions are made here for the revival of the nonmonetary work and production in the families and local communities, i.e. for empowering people to manage their own livelihood better and maintaining the control of their everyday life. The omission of nonmarket household work and production in the economic thinking distorts the picture of the national economy and makes it inadequate as the framework for the national economic planning and policies. The household, cultivation and industrial production are the distinct components of the human economy. The household and cultivation cannot be accommodated into the narrow physical-mathematical framework of industrial economy. Caring, cosiness and health as products of unpaid work in the households do not fit in, neither do sunshine, rain and fresh air or the life processes of microbes and worms in the soil as inputs to the 22 Figure 5. The Triangle of the Human Economy HOUSEHOLDS 1. Skills & ability 2. Unpaid work 3. Care, wellbeing CULTIVATION INDUSTRY & TRADE 1. Life in nature 2. Ecological cultivation 3. Production of food, other necessities 1. Raw materials & fuel 2. Extraction and refining 3. Business for profit EXPLANATIONS 1. Basic preconditions 2. The process 3. The purpose Graph: Hilkka Pietilä The basic pillars of the human economy, which have to collaborate in order to bring about sustainable human welfare and livelihood. Each one of these components has different foundations and terms of operations. Therefore they also have to be taken into account according to their respective terms. The recognition of dynamics and interdependences within and between these components is the prerequisite of understanding the totality of provisioning the human needs in a sustainable manner. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------The households and local economies are major components in production of human welfare. The cultivation economy is an indigenous component in the totality of human economy. It produces the basic goods for satisfaction of basic human needs. It is a concrete interface between ecology and economy, where the human culture should operate with due respect to ecological laws. Each one of these components of human economy operates by its own logic. Now, only the logic and terms of the industrial economy are well known. The other components need to be further analysed and defined. And so needs the dynamism between these three. The triangle picture of human economy (Figure 5.) sees these three components each one in its own right of existence and thus helps us to see the links and dynamism within and between the three. There are links between the macro and micro, monetary and nonmonetary, visible and invisible, living and non-living, private and public in the reality of human subsistence. Some of these links are within the components, some are in between them. 23 The need to develop a new theory for the totality of human actions for sustainable livelihoods is challenging. Such a new theory and understanding of the operation of this triangle human economy, will lay a foundation for the kind of economic planning and policy-making, that seriously aim to provide for a sustainable and dignified livelihood for all people, instead of constant growth and accumulation of capital and power in the hands of the rich and the strong. The suggestions and visions in this paper are an effort to contribute to and stimulate the process towards such a new theory (Pietilä, 1997) References: Chadeau, Ann. (1992). What is Households' Non-market Production Worth? OECD Economic Studies No.18, Spring 1992. Cogoy, Mario. (1995). “Market and non-market determinants of private consumption and .their impacts on the environment”. Ecological Economics 13 (1995) 169-180. EUROSTAT, Statistical Office of the European Communities. (1998). Proposal for a Satellite Account of Household Production. DOC E2/TUS/4/98. Friberg, Mats. (1983). “Mot en civilisationskris? Sex bidrag till en tolkning”. In: Friberg, Mats and Galtung, Johan (Eds.), 1983. Krisen, Series of Akademilitteratur, Stockholm. Friberg, Mats. (1985). “The Greening of the Nordic Countries”. In Svensson, Hanne & Jackson, Hildur, (Eds.): Future Letters from the North. 1985. Heinonen, Visa. (1996). “An Individual Effort for the Common Good. Laura Harmaja as an early Finnish advocate of consumer policy and home economics.” A paper presented in the XVIII International Federation for Home Economics Congress in Bangkok 22.7.1996. National Consumer Research Centre, Helsinki. Housework Study. (1981). Part 8. Official Statistics of Finland XXXII:79. Ingelstam, Lars. (1980). Arbetets värde och tidens bruk - en framtidstudie. (The value of work and use of time - future study.) Stockholm, LiberFörlag INSTRAW. (1995). Measurement and valuation of unpaid contribution: accounting through time and output. Santo Domingo. Jungk, Robert. (1983). Under Conditions of Humanquake. An interview in IFDA Dossier 34, March/April 1983. Mäki, Uskali. (1991), in a lecture in UNU/WIDER, Helsinki. Niemi, Iiris & Pääkkönen, Hannu. (2001). Ajankäytön muutokset 1990-luvulla. (The Changes of Time-use in 1990s in Finland.) Statistics Finland, Helsinki. OECD. (1995). Household Production in OECD Countries. Data Sources and Measurement Methods. Paris. 24 Olin, Ulla. (1975). “A case for Women as Co-managers. The Family as a General Model of Human Social Organization and its Implications for Women's Role in Public Life.” In: Tinker, Irene and Bo Bramsen, Michele (Eds.), Women and World Development. Washington l979. Overseas Development Council. Perkins, Patricia, E. (1998). “The Potential of Community-based Alternative to Globalization.” DEVELOPMENT. The Journal of the Society for International Development, Volume 41 No 3 September 1998. 61-67. Pietilä, Hilkka. (1988). Vallan vaihto. Naisen ajatuksia politiikasta, taloudesta ja tulevaisuudesta.(The Shift of Power. Woman's thoughts on politics, economy and future). Porvoo, WSOY (Finland). Pietilä, Hilkka. (1989). “The Environment and Sustainable Development. Reflections on ‘Our Common Future’". Presentation in Africa-Europe Encounter, Porto Novo, Benin. IFDA Dossier 77, May/June 1990. Pietilä, Hilkka. (1990 a). “Daughters of Mother Earth. Women's culture as an ethical and practical basis for sustainable development”. In Leila Simonen (Edit.). Finnish Debates on Women's Studies. Contributions by Finnish Scholars to the Fourth International Interdisciplinary Congress on Women. New York 1990. Tampere. Pietilä, Hilkka. (1990 b). “The Daughters of Earth: Women's culture as a basis for sustainable development”. In: Engel, J.R. & Gibb Engel, Joan (ed.): Ethics of Environment and Development. London/Belhaven Press. Pietilä, Hilkka. (1991). “Beyond the Brundtland Report”. In: Mark Macy (Ed.): Healing the World - and Me., Indianapolis/Knowledge Systems, Inc. Pietilä, Hilkka. (1997). “The triangle of the human economy: household - cultivation industrial production. An attempt at making visible the human economy in toto.” Ecological Economics, The Journal of the International Society for Ecological Economics, 20 No 2 (1997) 113-127. Pulliainen, Kyösti & Pietilä, Hilkka. (1983). “Revival of non-monetary economy makes economic growth unnecessary (in small, industrialized countries)”. IFDA Dossier 35. Nion. Radford Ruether, Rosemary. (1983). Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theology. Boston/Beacon Press. Ruuskanen, Olli-Pekka. (1995). Options for Building a Satellite Account for the Measurement of Household Production. Working Papers, No 7. Statistics Finland. System of National Accounts, 1993. EUROSTAT, IMF, OECD, UN, World Bank. UNDP. (1995). Human Development Report, 1995. New York, Oxford/Oxford University Press,. United Nations. (1974). General Assembly Resolutions 3201 and 3202 (Special Session VI). 25 United Nations. (1996). Platform for Action and the Beijing Declaration, Fourth World Conference on Women, 4-15 September 1995, Beijing, China. UN/DPI, New York. Vihavainen, Marjut. (1995). Calculating the value of household production in Finland in 1990. Working Papers, No 6. Statistics Finland. Vorlaeten, Marie-Paule. (1995), personal exchange in WIDE Conference on Women and Alternative Economics, Brussels, May 1995. Waring, Marilyn. (1988). If Women Counted. A New Feminist Economics. San Francisco/Harper & Row, Note: An earlier version of this paper was published in Ecological Economics, Vol.20 (1997). Hilkka Pietilä: The triangle of the human economy: household – cultivation – industrial production. An attempt at making visible the human economy in toto. Copyright 1997, the graphics with permission from Elsevier Science.