COM 329, Contemporary Film

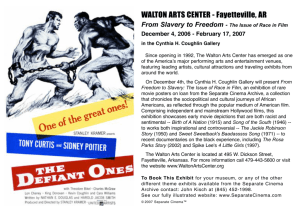

advertisement

1 COM 329, Contemporary Film Study Guide, Chaudhuri textbook South Asian and Indian Cinema Chapter 7: South Asian Cinema [NOTE: Although this chapter is titled South Asian, it is almost entirely devoted to India] -“Bollywood is tipped to become the West’s next Asian crossover phenomenon after Hong Kong cinema” -“Ray or rubbish” refers to the clear distinction between India’s “art”/“parallel” cinema and its popular film system (commonly referred to as Bollywood); Ray is Satyajit Ray, the late great filmmaker regarded as a national treasure [but whose films most Indians decline to watch] -“Parallel cinema”—art cinema that embraces intercommunal tolerance -Popular cinema evolved from the Indian epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, classical and folk theatre, and early 20th century Parsi theatre -History of popular Indian cinema extends back to 1896, with a three-studio system by the 1920s -Despite issues of regional, religious, and language (“mother tongue”) differences across India, there emerged an “all-India aesthetic” that assured the attraction of popular Indian film across all of India and to other regions of the world (e.g., Middle East, East Africa) -No official role of the government in popular Indian film industry, except for the National Board of Censors (legacy of British colonialism) -Angry Young Men films associated with a young Amitabh Bachchan -Indian popular film narrative structure as nonlinear, episodic—plots within plots and many flashbacks -Role of intertextuality in popular Indian films -Music in popular Indian film a hybrid of light classical Indian music, popular music, and Western orchestral -Playback singers and role of soundtracks in marketing Indian films -“Big B”—Amitabh Bachchan -The star system in Indian film -MTV-type dance sequences in Indian film -“Parallel cinema” or “New Indian Cinema”—songless, starless, and low-budget -Satyajit Ray—founder of parallel cinema; his 1950s “Apu Trilogy” a great inspiration for filmmakers to follow; influenced by Italian neorealism and French poetic cinema (e.g., Jean Renoir); his films covered a wide range of genres and issues -Government-established Film Finance Corporation (1960)--which became the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC, 1980)--and the National Film Institute (1961) were set up expressly to support parallel rather than popular cinema in India -Parallel cinema of the 1970s and 1980s belonged to the Third Cinema model of radical collective filmmaking; since then, two types of parallel cinema have been apparent—(1) “Middle Cinema,” which combines parallel cinema themes and popular cinema devices to appeal to a broader audience, and (2) a cinema of auteurs, which has flourished in Bengal and Kerala -“Tollywood”—Bengal film industry based in Tollygunge, South Calcutta -South India films—gaining ground on “Bollywood” (i.e., Hindi-language popular Indian film); languages are Tamil, Malayalam, and Kannada -Mani Ratnam—key South Indian filmmaker; works with music composer A. R. Rahman [who won an Academy Award for the score of Slumdog Millionaire in 2009] -Sri Lankan cinema—strong links with South Indian cinema -“Lollywood”—Pakistan’s main film industry, based in Lahore -Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka a film-producing center -Bangladesh’s “short films” underground movement 2 Chapter 8: Indian Cinema -With increasing international releases, Bollywood now has three audiences: (1) the core audience of the Indian poor, (2) the South Asian diaspora around the world, and (3) India’s middle class -The diasporic Indian (NRI, “non-resident Indian”) has moved to the center of the Bollywood narrative in recent years [NOTE: The book does not emphasize the role of “Desis,” children of diasporic Indians who also serve as an important focus and an important real-life film market.] -Key films emphasizing Bollywood’s culturally unifying role—Lagaan (2001, see also Close Analysis on p. 166), Mani Ratnam’s “Terrorism Trilogy,” Roja (1992), Bombay (1995) and Dil Se (1998; see also Close Analysis on p. 171) -The Bollywood Romance—the dominant genre of the 1990s, replacing the action and revenge dramas of the 1970s and 1980s; characterized by a love triangle, love based on friendship, an examination of the “arranged love marriage,” NRI characters, foreign locations, a style reminiscent of MTV and advertising, with conspicuous consumption and product placement -The Bollywood Brat Pack—many directors, and stars, are offspring of influential industry professionals (movie dynasties), including Karan Johar (Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, 2001) -The exception to the Brat Pack phenomenon is Shah Rukh Khan, who emerged from a very humble background -“Chiffon and roses” brand of Bollywood romance focusing on super-rich lifestyles, introduced by Yash Chopra -Role of wholesome family entertainment in Bollywood -Star system—most Indian films are “carried” by the male star (e.g., Shah Rukh Khan), but some female stars are noteworthy (e.g., Kajol, whose off-screen personality is distinctively post-feminist) -Endorsement of global consumerism in Bollywood films—malls as temples of consumerism -Mani Ratnam—a distinctive background, his use of real political conflicts in his trilogy; his Bombay was the first Indian popular film to include a Hindu-Muslim marriage -Indian expatriate filmmakers—two women (!!)--(1) Mira Nair (trained abroad, including with US documentarist D. A. Pennebaker; films include Salaam Bombay (1988), Monsoon Wedding (2001), which the book says is reminiscent of Dogme 95 (!)); and (2) Deepa Mehta (worked in Canadian television; films include her “Elements Trilogy” Fire (1996, see also Close Analysis on p. 169), Earth (1998), Water (2005))