Kevorkian, Jack (1928-)

advertisement

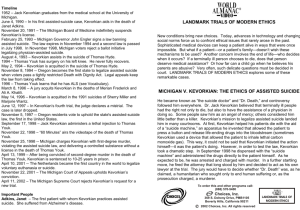

Kevorkian, Jack (1928-) Encyclopedia of World Biography, Edition 1 1998 Kevorkian, Jack (1928-) BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY Jack Kevorkian (born 1928) became known as "Dr. Death," in part, because he assisted many people in committing suicide. Kevorkian considered the right to die to be a basic personal right, having nothing to do with government laws. He felt there could be a time when a suffering person may choose death and that physicians should be allowed to assist. Jack Kevorkian originally wanted to be a baseball radio broadcaster, but his Armenian immigrant parents felt that he should have a more promising career. So he became a doctor, specializing in pathology. Kevorkian worked primarily with deceased people, performing autopsies in order to study the essential nature of diseases. His parents never imagined that he would be the one to design the first modern Thanatron (Greek for "death machine") nor that he would be the first to help people use this machine. Kevorkian was born on May 28, 1928, in Pontiac, Michigan. He was raised in an Armenian, Greek, and Bulgarian neighborhood. Kevorkian attended the University of Michigan medical school and graduated in 1952. Kevorkian initially received his macabre nickname, "Dr. Death," for his pioneering medical experiments in the 1950's. He photographed the eyes of dying patients in order to determine the exact time of death. He believed that this precise knowledge would yield valuable information about diseases. Kevorkian served as associate pathologist in three Michigan hospitals: St. Joseph's, Pontiac General, and Wyandotte General. He also worked as a pathologist in some Los Angeles hospitals. Kevorkian was the founder and director of the Checkup Multi-Phase Medical Diagnostic Center in Southfield, Michigan and Chief of Pathology at the Saratoga General Hospital in Detroit. He published more than 30 professional journal articles and booklets, including Prescription Medicine: The Goodness of Planned Death. As Kevorkian witnessed the suffering of terminally ill patients, he became convinced that they had a moral right to end their lives when the pain became unbearable, and that doctors should assist in this process. To that end, he designed and constructed a machine that started a harmless saline intravenous drip into the arm of a person wishing to die. When the patient was ready, he or she would press a button that would stop the flow of the harmless solution and begin a new drip of thiopental. This chemical would put the patient into a deep sleep, then a coma. After one minute, the timer in the machine would send a lethal dose of potassium chloride into the patient's arm, stopping the heart in minutes. The patient would die of a heart attack while in a deep sleep. The death, according to Kevorkian, would be quick, painless and easy. For a person suffering from the pain of terminal cancer or some other disease, the machine would provide what Kevorkian called a painless "assisted suicide." First Assisted Suicide In June 1990, Kevorkian assisted in the first of many physician-assisted suicides. He used his machine to hasten the death of Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old woman from Portland, Oregon, who was suffering from Alzheimer's disease. The State of Michigan immediately charged him with murder, although the case was later dismissed, largely due to the unclear state of Michigan law on assisted suicide. By 1999, Kevorkian had been present at the death of nearly 130 people. In each case he made his assistance known to the public, as part of a determined campaign to change attitudes and laws on physician-assisted suicide. Public Reaction Many agreed with what Kevorkian was doing. On June 21, 1996, during an interview with a Detroit radio station, famed broadcast journalist Mike Wallace said, "I am an old man. I'd be the first, if necessary, to go to Kevorkian." Wallace said he could imagine seeking Kevorkian's services if he were suffering from a painful and lingering disease. "You have the right as a human being to do what you want to do with yourself," said Wallace. Others disagreed with this opinion. The National Spinal Cord Injury Association opposed assisted suicide because there were better ways around the problem. "Refusing medical treatment is your choice to die how you wish--in your own home with your family or in your hospital bed. Assisted suicide is you giving somebody the power to take your life away. A person is given the power to kill." Legal Issues Despite constant legal problems, Kevorkian continued to assist with suicides. In 1994, he faced murder charges in the death of Thomas Hyde, who suffered from a terminal nerve illness known as Lou Gehrig's disease. Jurors agreed with the argument that there was no statute against assisted suicide in the state of Michigan, and thus Kevorkian could not be found guilty. The Kevorkian team of defense lawyers won yet another acquittal. They successfully argued that a person may not be found guilty of criminally assisting a suicide if that person had administered medication with the "intent to relieve pain and suffering," even it if did hasten the risk of dying. Kevorkian was prosecuted four times in Michigan for assisted suicides, and he was acquitted in three of those cases; a mistrial was declared in the fourth. In 1998, the Michigan legislature enacted a law making assisted suicide a felony punishable by a maximum five year prison sentence or a $10,000 fine. This law went into effect months before a ballot proposition legalizing assisted suicide was defeated by Michigan voters. It closed the loophole on relief of pain and suffering, which Kevorkian's lawyer's relied upon to obtain acquittals. The statute provides that a person who knows another intends to kill himself and provides the means, participates in the suicide, or helps to plan the suicide, is guilty of a felony. Kevorkian proceeded with what he thought was right, and challenged authorities to arrest and prosecute him. On September 17, 1998 he took the ultimate step in the assisted suicide of Thomas Youk. Instead of asking the patient to press the button to inject the fatal dose of drugs, Kevorkian, after speaking gently to the man suffering from Lou Gehrig's disease, administered the drug himself. Furthermore, he videotaped the entire event so there would be no doubt of what he had done. He then gave the tape to the television show 60 Minutes. The episode was aired for the whole world to see. Shortly thereafter, Kevorkian was arrested in Michigan for first-degree murder. In this case, when he injected Thomas Youk with the lethal drugs, he committed euthanasia, or mercy killing, not assisted suicide. Kevorkian was also charged under the felony law that bans assisted suicide, which went into effect approximately two weeks before Youk's death. Kevorkian decided to represent himself in the Youk murder trial. On March 26, 1999, he was convicted of the lesser offense of second degree murder by a Michigan jury. In the maelstrom of opinion created by his beliefs, Kevorkian continued his campaign for legalized physician-assisted suicides. He expected to be arrested, and he often was. He felt he was doing his best for people who were terminally ill and suffering great discomfort. In so doing, Kevorkian raised national awareness of assisted suicide and forced the courts and legislatures to make decisions on this controversial issue. Source Citation: "Kevorkian, Jack (1928-)." Encyclopedia of World Biography. Detroit: Gale, 1998. Gale Student Resources In Context. Web. 15 Nov. 2010. 'Dr. Death' served us all with time in prison USA Today, June 6, 2007 'Dr. Death' served us all with time in prison Byline: Sidney Wanzer What has Jack Kevorkian, now that he has been released after eight years in prison for murder, actually accomplished? In 1998, he openly dared Michigan to put him in prison for ending the life of a suffering person, and the state did just that. His detractors say he flouted the laws of our society and forced the state to punish him for his deeds. His supporters say he did all of us a service by pointing out what he thought was the right of a dying, suffering person to have autonomy over the manner and timing of death. In doing so, he brought this matter to the acute attention of the public in a way that no one had done before. The latter is the important outcome. Kevorkian forced us to examine critically the need for new laws that will allow dying persons to end life in certain circumstances when this is the only truly compassionate treatment. This need to actively end life is a very infrequent happening. The more common and proper sequence of events is that, as a fatal disease progresses, a point will come at which efforts to cure or restore some semblance of well-being are destined to fail. The astute physician will help the patient and family recognize and define that critical point, so that a decision may be made properly to switch from curative efforts to comfort care only. This considered decision to redefine goals has the important effect of allowing the patient, family and physicians to stop expending emotional energy in fruitless directions and instead to concentrate on preparing for dying. Comfort care becomes the only goal -- to shepherd the patient through the dying process with as much calm and choice as is possible. This approach works because modern comfort care is now sophisticated and effective. It is possible to deliver meticulous attention to all the facets of pain relief and to prescribe symptomatic treatment for all forms of distress -- physical and emotional -- with a degree of efficiency that allows a reasonably comfortable death. However -- and this is a big however -- there are occasional instances in which comfort care is applied with the greatest skill possible, and yet the patient continues to suffer intolerably in spite of all measures. This happens in the practicing lifetime of a physician only rarely, but it does happen. In my experience, these situations are self-evident. They cry out that physician-assisted death is the only humane and compassionate thing left in the spectrum of treatment at the end of life. Modern medicine is miraculous, but when its use extends the dying process inappropriately, it can be a disservice to the patient. When a patient actively invites death, it is not suicide, which most of us regard as an irrational act of a mentally ill person. Rather, it is the patient asking for treatment to end suffering by the use of a fatal dose of medication -- an option that is legal only in Oregon. Our country needs a law in every state, similar to that in Oregon, where almost 10 years of experience has shown that we can allow physicians to prescribe a lethal dose of a barbiturate for terminally ill patients who are suffering intolerably. In that state, there has been no abuse and no slippery slope that was so vociferously predicted. From 1998 (when the law became operative) through 2006, only 292 patients utilized the law to end their lives in order to end suffering, after careful prerequisites. This number is tiny compared with the 85,755 Oregonians who died from the same diseases but without barbiturates. Without fearing abuse, we should permit intolerably suffering patients the right to exert this ultimate autonomy in choosing the manner of their dying. Oregon and three countries in Europe allow this, but we all should have that option. Doctors shouldn't have to go to jail for acting compassionately. Source Citation: Wanzer, Sidney. "'Dr. Death' served us all with time in prison." USA Today 6 June 2007: 13A. Gale Student Resources In Context. Web. 15 Nov. 2010. Dr. Kevorkian's wrong way The New York Times, June 5, 2007 Dr. Kevorkian's wrong way Dr. Jack Kevorkian -- a k a ''Doctor Death'' for helping chronically ill and terminally ill patients commit suicide -- has emerged from prison as deluded and unrepentant as ever. Brushing aside criticism by other supporters of medically assisted suicide that his tactics were reckless and harmful to their cause, Dr. Kevorkian asserted: ''I did it right. I didn't care what they did or didn't do. When I'm going to do it, I'm going to do it right.'' The irony, of course, is that he did it wrong, and in performing assisted suicides so badly, he besmirched the movement he hoped to energize. If his antics provided anything of value, it was as a reminder of how much terminally ill patients can suffer and of the need for sane and humane laws allowing carefully regulated assisted suicides. Dr. Kevorkian first drew national attention in 1990 when he hooked up a 54-year-old Alzheimer's patient to his homemade suicide machine and watched as she pushed a button to release lethal drugs. By the time he was jailed nine years later, he claimed to have helped more than 130 terminally ill or chronically ill patients take their own lives. What tripped him up was his ego and a limitless appetite for publicity. In a procedure that was taped to be shown later on national television, he gave the lethal injections to a 52-year-old man with Lou Gehrig's disease -- thereby moving beyond assisted suicide to euthanasia. He challenged prosecutors to indict him, apparently hoping the trial would provide a showcase for arguing his cause. But the judge blocked any testimony from family members who supported the death and disallowed evidence about the patient's suffering and consent as irrelevant in a murder trial. The jury found the doctor guilty of second-degree murder. The fundamental flaw in Dr. Kevorkian's crusade was his cavalier, indeed reckless, approach. He was happy to hook up patients without long-term knowledge of their cases or any corroborating medical judgment that they were terminally ill or suffering beyond hope of relief with aggressive palliative care. This was hardly ''doing it right'' as Dr. Kevorkian likes to believe. By contrast, Oregon, which has the only law allowing terminally ill adults to request a lethal dose of drugs from a physician, requires two physicians to agree that the patient is of sound mind and has less than six months to live. Now California is about to vote on a similarly careful measure. One of its sponsors cites Dr. Kevorkian as ''the perfect reason we need this law in California. We don't want there to be more Dr. Kevorkians.'' Source Citation: "Dr. Kevorkian's wrong way." New York Times 5 June 2007: A22(L). Gale Student Resources In Context. Web. 15 Nov. 2010. Jack Kevorkian U*X*L Biographies, 2003 Born: c. 1928 in Pontiac, Michigan, United States Nationality: American Occupation: Pathologist Jack Kevorkian Jack Kevorkian, an advocate of legalized euthanasia, has defied the law by helping people with terminal illnesses commit suicide. Physician Jack Kevorkian considers himself an angel of mercy, but his critics have dubbed him "Dr. Death." From June 1990 through May 1998, he helped at least one hundred ill people commit suicide. The result: Kevorkian has single-handedly—and single-mindedly—raised a storm of debate over the rights of patients to choose the moment of death, and what role doctors should play in that decision. In the process, he has forced the medical and legal professions to confront a long taboo subject. Kevorkian has been prosecuted for some of the suicides he assisted and was acquitted each time until the suicide death trial of Thomas Youk in 1999 when he was found guilty of first-degree murder. Unconventional views Born May 26, 1928, in Pontiac, Michigan, Kevorkian is a longtime euthanasia advocate, who is well outside the medical mainstream. Euthanasia (pronounced you-thuh-NAY-zhuh) is helping or letting fatally ill or injured people die as painlessly as possible. Kevorkian's unconventional views set him apart from his colleagues early in his career. While serving his internship as a pathologist at the University of Michigan hospital, he proposed that death-row prison inmates be made unconscious so that their living bodies could be used as the subjects of medical experiments. His dedication to that plan resulted in his dismissal from the hospital, and he finished his internship at Pontiac General Hospital. The last staff position he held was in 1982, at the Pacific Hospital in Long Beach, California. When that job ended, he was unable to find another. He told Isabel Wilkerson in the New York Times that this was because his revolutionary ideas were too frightening for hospitals to accept. "I don't apply anymore," he declared. "I've written off the medical profession. I'm an outsider. I'm the lowest in the profession." Despite the medical establishment's alienation from him, there were never any formal complaints filed or disciplinary actions taken against him. After leaving Pacific Hospital, Kevorkian moved to a small apartment in Royal Oak, Michigan. For several years he occupied himself mainly with writing for European medical journals. Many of the articles he wrote reflected his continuing preoccupation with euthanasia. In one issue of Medicine and Law, he suggested setting up suicide clinics, writing: "The acceptance of planned death implies the establishment of well-staffed and well-organized medical clinics ... where terminally ill patients can opt for death under controlled circumstances of compassion and decorum." In the late 1980s Kevorkian devoted more time to developing a working suicide device—a simple setup that mimics an execution by lethal injection. Three bottles are suspended from a metal framework. One contains a harmless saline solution; one contains thiopental, a pain killer; the other, potassium chloride. In 1989 the model for the device, built with about forty-five dollars worth of materials, was ready to be used. Kevorkian tried to advertise his invention in medical journals, but was turned away. Frustrated, he sold his story to local newspapers. Janet Adkins The publicity earned him a guest appearance on the Donahue talk show in April 1990. Kevorkian suggested that death row inmates be allowed to use his device rather than waiting for execution; their organs could then be used for transplants. One person who saw the show was Janet Adkins of Portland, Oregon. She was a fifty-four-year-old professor of English, an active, vital woman who enjoyed hang gliding, backpacking, world travel, and music. In 1987 she had begun experiencing slips in memory, along with difficulties in reading music and spelling. In 1989 an Oregon doctor diagnosed the onset of Alzheimer's disease, an incurable condition that causes progressive loss of memory, insight, and other mental functions. Adkins was horrified by the prospect of experiencing a decline in the quality of her life. Her husband recalled her response to the diagnosis in People magazine: "Right then Janet said, `I want to exit.'" Both the Adkinses were long-standing members of the Hemlock Society, which supports doctor-assisted suicide, so her reaction was not unexpected. Her three sons persuaded their mother to try experimental therapy for Alzheimer's, but it proved ineffective. Before long, Adkins and her husband boarded a plane for Detroit, Michigan, determined to consult with Dr. Kevorkian. Over a luncheon meeting, Kevorkian confirmed the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, judged Adkins clearheaded enough to make her fateful decision, and agreed to help her see it through. On June 4, 1990, using his suicide machine, he did. When the authorities arrived, it was unclear what crime, if any, had been committed. Assisting suicide is a felony in most states, but Michigan law regarding it was at the time vague. There was no clear statement against it, and legal examples of prior incidents only confused the issue. In 1920, for example, a Michigan man was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison after he placed poison within the reach of his wife, who suffered from multiple sclerosis, a disease affecting the muscles. In 1983, however, the Michigan Court of Appeals dismissed murder charges against a man who had an affair with the wife of a friend, then gave a loaded gun to the depressed husband, who shot himself with it. While the legalities of Kevorkian's case were being sorted out, an injunction was filed forbidding him to use the suicide machine again. AMA reaction Kevorkian's action drew swift, sharp criticism from the medical establishment. Although the American Medical Association (AMA) does support "passive euthanasia," such as withholding food from a patient in an irreversible coma, it stands firmly against active euthanasia. The reasoning, supported by medical ethicists, is that killing on demand will eventually lead to erosion of medicine's claim to be a moral profession. Judith W. Ross, professor of medical ethics at the University of California, Los Angeles, explained in the New York Times that because of the trust factor vital to good physician-patient relations, "even if society wants something like this done, someone other than doctors should do it." Once the power to kill is legitimized, many doctors say, the chances for abuse and misuse skyrocket, leaving patients justifiably uneasy about where their physicians stand on the issue and what kind of value judgments might be made about the quality of their lives. Furthermore, doctor-assisted suicide seems to be in direct conflict with the Hippocratic oath doctors take, which states: "I will give no deadly drug if asked, nor will I make a suggestion to its effect." Adkins's case struck many as particularly misguided. She was relatively young, in excellent physical shape, and able to carry on normal conversations. Condoning her suicide paves the way for society to give up its responsibility for improving conditions for the elderly and incurably ill, in the opinion of many ethicists—specialists in what is good and bad in terms of professional standards of conduct. Creighton Phelps, the National Alzheimer's Association's vice president for medical and scientific affairs, stated in the Chicago Tribune that the association was "saddened by the tragic case" but did not approve of Adkins's suicide. "We believe hers was a very personal decision.... However, we also must affirm the right to dignity and life for every Alzheimer's patient.... We advocate life." Other reactions Death-with-dignity groups generally are in favor of a witnessed, legal, written suicide request, with two independent doctors verifying that the patient's condition is irreversible and unbearable. Alzheimer's disease is notoriously difficult to identify with absolute certainty, with doctors admitting a 30 percent margin of error, and Kevorkian was not well-qualified to diagnose it. Furthermore, because insight is one of the first things to be lost during the course of the disease, a diagnosis of Alzheimer's is inconsistent with the statement that Adkins was able to make her own decisions. Dr. Lawrence K. Altman commented on the case in the New York Times: "Many physicians who criticized Dr. Kevorkian's action said it was not clear what kind of patient-doctor relationship the doctor had formed with Mrs. Adkins. They specifically questioned whether depression might have clouded Mrs. Adkins's judgment and whether she had been thoroughly examined for depression, which, unlike Alzheimer's, is a treatable disease." He noted that depression is common after a diagnosis of Alzheimer's and other diseases, and many people can eventually overcome the depression. Adkins's family and friends insist that she was competent to make her decision and had every right to do so, and they defend Kevorkian's part in her death. "Quality of life was everything with her," stated her son, Neil, in the New York Times. "She wanted to die with her dignity intact." Kevorkian claimed in the Chicago Tribune, "She thanked me as she was going under.... She understood everything. She just couldn't live the life she wanted to live anymore." He has dismissed his critics as "brainwashed ethicists," "nonthinking physicians," and "religious nuts," and scoffed at the idea that his invention would encourage people to kill themselves. "They already do that," he pointed out to Lisa Belkin in the New York Times. "They jump out of buildings, they blow their brains out, they drink lye. Is that better?... My ultimate aim is to make euthanasia a positive experience. I'm trying to knock the medical profession into accepting its responsibilities, and those responsibilities include assisting their patients with death." Whether he is right or wrong in his convictions, Kevorkian has "dramatized the issue of the right to die in a way few physicians have in the past," according to Dr. Altman. "The publicity ... is challenging more people to take public stands about the issue, to think about the way they want to die if they become chronically ill and to discuss those wishes with their families and friends." License is revoked In 1991 Kevorkian's Michigan medical license was revoked, but his assisted-suicide mission never slowed. In 1993 the state passed a temporary law—directly targeting Kevorkian—that banned assisted suicide. Again, the doctor was undeterred. In fact, he has welcomed legal challenges, hoping court proceedings would at last establish the legal right to a dignified death. While the legislative and judicial responses to assisted suicide have been mixed, Kevorkian has had his share of victories: In 1994 Michigan's temporary law banning assisted suicide expired. In 1996 a U.S. District judge struck down Washington State's assisted suicide ban, which had been passed through a referendum. And a federal judge concluded the 14th Amendment protects the right to physician-assisted suicide. More trials In August 1993 Kevorkian was charged with violating Michigan's assisted suicide ban in the death Thomas Hyde Jr., age thirty, a victim of Lou Gehrig's disease. Following one of his arrests, the doctor carried out an eighteen-day juice fast in jail. After he was acquitted in Hyde's death in May 1994, the New York Times reported that several jurors said they believed defense arguments that Kevorkian's true goal was to relieve Hyde's suffering. In 1996 Kevorkian stood trial twice—once in March and once in May—for two suicides committed in 1993 and two in 1991, respectively— and also participated in more suicides. The New York Times quoted his flamboyant attorney, Geoffrey Fieger, as saying the trials "are about whether we have the right to decide for ourselves that enough suffering is enough, and whether a physician can help a rational, competent adult seek a soft landing." Kevorkian was again found not guilty in both 1996 trials—and a survey published in the New England Journal of Medicine implied his cause had public support. Two-thirds of Michigan residents and 56 percent of the state's doctors supported legalized doctor-assisted suicide, the survey concluded. Kevorkian, in March 1996, told the New York Times, "This is the very essence of human autonomy, something that goes way beyond a so called `right' and I am honored as a healer to help any suffering patients whose condition medically warrants it.... They'll have to lock me up to stop me." In 1998, the Michigan House of Representatives passed a bill making it illegal to assist suicide. One day later Kevorkian assisted in another suicide. Michigan governor John Engler signed the bill into law effective in late 1998. Stands trial for fifth time On March 22, 1999, Kevorkian stood trial for the suicide death of Thomas Youk, a 52-year-old man suffering from Lou Gehrig's disease. Prosecutors in the case accused Kevorkian of first-degree murder and during the course of the trial showed a videotape of Kevorkian giving Youk a lethal injection in September of 1998. The videotape had been shown on the nationally televised news show 60 Minutes when Kevorkian was interviewed by Mike Wallace. Kevorkian acted as his own attorney during his trial, foregoing advice from the presiding judge, Jessica Cooper, who repeatedly advised him to seek legal counsel. Cooper stated "This man [prosecutor] is attempting to convict you of murder in the first degree. If your attorneys are telling you that there's something going on here that you need to object to, than you need to get up and object." Kevorkian opted to disregard the judge's advice and eventually was convicted for first-degree murder. Kevorkian was sentenced to 10 to 25 years in prison. At the sentencing, Cooper admonished Kevorkian, "No one, sir, is above the law.... You were on bond to another judge when you committed this offense; you were not licensed to practice medicine when you committed the offense. And you had the audacity to go on national television, show the world what you did, and dare the legal system to stop you. Well sir, consider yourself stopped." The imprisoned doctor plans to appeal his case. Source Citation: "Jack Kevorkian." U*X*L Biographies. Detroit: U*X*L, 2003. Gale Student Resources In Context. Web. 15 Nov. 2010. Euthanasia Gale Student Resources in Context, 2010 Euthanasia Euthanasia is the act of causing or permitting the death of someone who may be suffering from an incurable or terminal illness, often as a way to end the suffering of that individual. In its oldest and most general sense, the word euthanasia simply means good, or gentle, death. Today, however, the term is, for many, synonymous with other words or phrases, like suicide, mercy killing, death with dignity, physicianassisted suicide (PAS), and physician-aided dying (PAD). History It is generally acknowledged that the act of mercy killing has been practiced in human cultures throughout history. The issue is discussed in the writings of several early Greek philosophers, who considered it to be morally acceptable; soon after the fall of Rome, however, the rise of the Christian church and its sway over civil law rendered mercy killing both immoral and illegal. Still, the practice is known to have been carried out in secret, right up to the present day. The term euthanasia makes its first appearance in the writings of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English scholars. It was not until 1935, however, when the Voluntary Euthanasia Society was formed in Britain, that anyone thought to challenge current laws forbidding euthanasia. Although as many as half the population at the time supported some form of PAS, attempts to legalize the practice invariably failed. During World War II, in 1939, Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler signed a decree authorizing physicians throughout Germany to "euthanize" tens of thousands of mentally and physically disabled children and adults. As part of his program to racially cleanse the German population, it was the first step that would ultimately lead to the death of millions more Jews, Romani (Gypsies), Catholics, and homosexuals. Following the war, revelations about the scope and devastation of the program would have a profound impact on public opinion regarding euthanasia. Beginning in the 1940s, as medical technology advanced, so too did the means by which the sick and dying could be kept alive. Instead of dying at home, more and more were being treated, and dying, in hospitals. A strict interpretation of the Hippocratic Oath often meant that doctors would attempt to maintain a person's life for as long as was physically possible, even if it went against the wishes of their patients or their patients' families. In 1975, a New Jersey woman, Karen Ann Quinlan, was admitted to a hospital for a drug and alcohol overdose. She had slipped into a coma, a persistent vegetative state in which the woman's brain had been damaged beyond repair. Knowing that she might never regain consciousness, Quinlan's parents asked the hospital to remove her from life support, but the hospital refused. A year and several court hearings later, the parents finally won their battle to have her removed from life support, though she continued to live in a vegetative state for another ten years before dying of pneumonia in 1986. Also in 1975, British journalist Derek Humphry agreed to help his own wife, who endured terrible pain from an incurable form of cancer, end her suffering by giving her a fatal dose of medication obtained from an unnamed physician. After publishing a book about the affair, in 1978, authorities investigated but chose not to prosecute Humphry. He later moved to the United States where he formed the Hemlock Society, to promote public tolerance for the right to die by terminally ill patients. By the 1980s, and with the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, public opinion began to shift, and the discussion soon included not only the right to die by removal of life support or other life-sustaining treatments, but the right of physicians to actively assist in a person's death. In 1986, the American Medical Association withdrew its opposition to the removal of life support for patients in a persistent vegetative state. In 1990, Janet Adkins, an Oregon woman recently diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, took her own life with the assistance of a retired Michigan pathologist named Jack Kevorkian. Kevorkian later claimed to have helped as many as 150 others take their own lives. It was, in his words, a doctor's duty to help the terminally ill carry out their own wish to die. Types of Euthanasia As it pertains to patients with incurable diseases, or who are terminally ill, euthanasia can be either voluntary or involuntary. Voluntary euthanasia is performed at the explicit request of the patient, either by advance directive, a "Do Not Resuscitate" (DNR) order, or a living will. Involuntary euthanasia is performed without a patient's consent or directive; those on both sides of the debate are likely to agree that involuntary euthanasia should be treated as a homicide. As such, the debate over euthanasia is mostly about the ethics of allowing an individual to voluntarily choose death and the legal status of those who choose to assist in the process. Euthanasia can also be categorized as passive or active. Passive euthanasia involves the removal of life-support systems used to sustain a patient's life, or the withholding of a treatment that might prolong the life of a patient. Active euthanasia requires that a doctor or other third party, at the request of the patient, directly administer a lethal dose of a drug to the patient—usually through injection. Alternatively, the doctor may simply provide the drugs and/or apparatus to the patient, allowing the patient to self-administer the lethal dose. This is the method used by Kevorkian, who named his device the Mercitron, in the 1990s. Controversy Although many oppose euthanasia in any form, arguing that life should be preserved at all costs, the debate over passive euthanasia has become less heated, following court rulings that recognize the rights of patients to refuse medical treatment. Still hotly contested, however, is whether or not other active forms of euthanasia, such as PAS, should be made legal. For many, the question of whether it is right to take the life of another person, no matter what the circumstances, is unambiguous. The Christian moral tradition, as well as that of other religions, expressly prohibits killing another human being. The sixth commandment, "Thou shalt not kill," trumps all other considerations. Opposed to this view is the notion that individuals should have the right to choose for themselves the treatment they receive toward the end of life. This idea was part of a larger shift in attitudes during the 1960s and 1970s, as the civil rights movement gathered steam. People were growing wary of the medical establishment; suspicions about the motives of doctors and the institutions they served undermined the public trust. For many, the end to suffering is the most important consideration. These advocates for PAS argue that a life of pain and suffering is no life at all, and that the only compassionate course of action is to give those patients the chance to end their suffering and choose when and where to spend their final days. However, since euthanasia is about making the choice of whether, and when, to die, opponents argue that it is a choice too easily abused or misused. Patients who may be suffering from temporary depression, are mentally unstable, or are simply unable to cope with the conditions of their illness may not be in the best position to make a life or death decision. Further, they argue, active, voluntary euthanasia opens the door to abuse when, for example, a doctor sidesteps the normal safeguards or readily accedes to a patient's wishes before all the facts about his or her condition or prognosis are known. PAS—in which the patient is required to administer the lethal dose of drugs themselves—is more widely accepted, though opponents of euthanasia find it just as morally reprehensible as the direct, active form. Nor is it clear, opponents suggest, that PAS is less prone to the same sorts of abuse. The Law On the whole, however, PAS has not enjoyed popular support. Voter referendums in Washington and California failed; in Michigan, Kevorkian's home state, a similar measure was also voted down. In Belgium and the Netherlands, assisted suicide is still technically illegal, but is widely accepted. In 1997, Oregon became the first U.S. state, and the only place in the world, to legalize PAS, by enacting its Death with Dignity Act. Right-to-die advocates have attempted to overturn state bans on assisted suicide on constitutional grounds. In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the constitution does not guarantee an individual's right to euthanasia and that states are free to enact their own laws governing the issue. Source Citation: "Euthanasia." Gale Student Resources in Context. Detroit: Gale, 2010. Gale Student Resources In Context. Web. 15 Nov. 2010.