Chorney 1

Meagen Chorney

4 April 2012

Bite Me: Abjection, Eroticism and the Breaking of Skin in True Blood

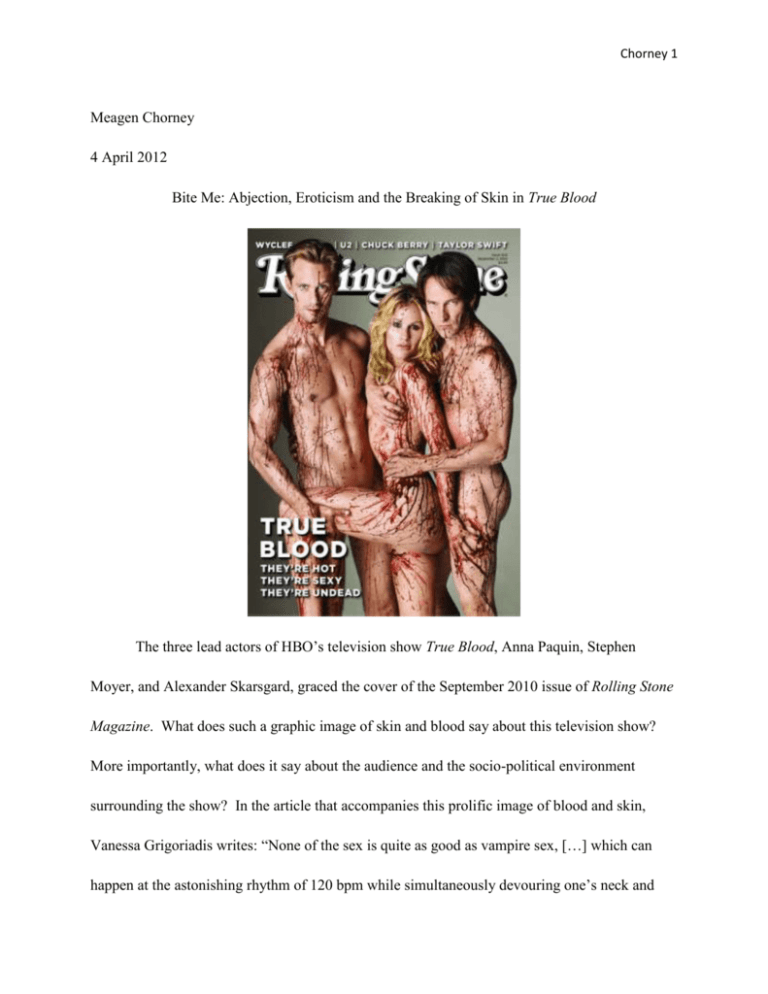

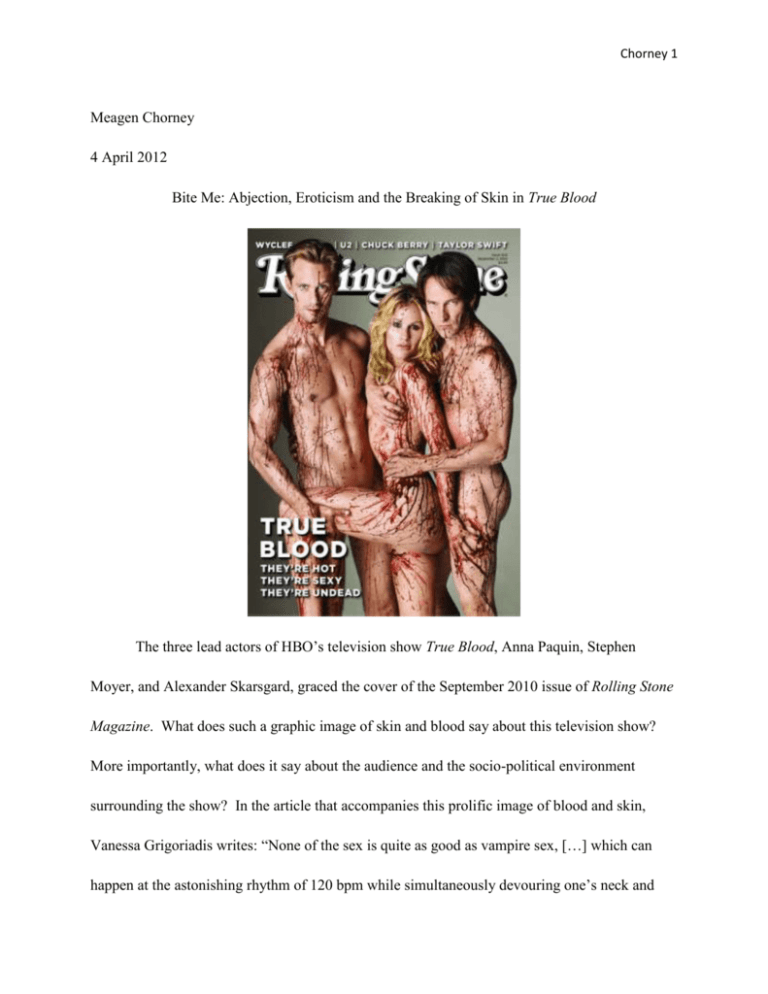

The three lead actors of HBO’s television show True Blood, Anna Paquin, Stephen

Moyer, and Alexander Skarsgard, graced the cover of the September 2010 issue of Rolling Stone

Magazine. What does such a graphic image of skin and blood say about this television show?

More importantly, what does it say about the audience and the socio-political environment

surrounding the show? In the article that accompanies this prolific image of blood and skin,

Vanessa Grigoriadis writes: “None of the sex is quite as good as vampire sex, […] which can

happen at the astonishing rhythm of 120 bpm while simultaneously devouring one’s neck and

Chorney 2

making your eyes roll back in your head.” Another interview with creator Alan Ball calls True

Blood “the most perverse, and yes, sexiest, show on TV” (Ball). Both articles reflect on True

Blood’s use of not only sex, but violent and (what could be considered) ‘perverse’ sex. I see

‘perverse’ here as falling within the connotation of non-normative sexual acts based on societal

conventions. The skin and blood and implication of a threesome in the Rolling Stone Magazine

cover is significant because it epitomizes the kind of violent and transgressive sexuality that the

show promotes. It is not just about naked skin but about the breaking of that skin; the drawing of

blood from the body. What should be a horrific image (three actors covered in blood) is instead

presented as an appealing, even sexy, image. This image evokes abjection and eroticism, as does

the show.

The vampires of True Blood are accepted by many in the show’s audience. This is

evidenced by fan pages of True Blood on the website Facebook in which fans express their

adoration for these characters. For example, one fan page has over nine million fans (“True

Blood”). Why is this show appealing? How can vampires project an erotic and abject image at

the same time? While it could be argued that the image of a female constantly being bitten by

vampires is derogatory, does True Blood counter this argument in support of female sexuality? I

argue that True Blood shows vampires as abject through the breaking of skin, but also eroticizes

their image to assert female sexuality and the power of choice.

From a phenomenological standpoint, a subject’s relationship to the world is experienced

by the boundary of skin. Skin separates the self from the Other. We can touch the Other, but we

Chorney 3

do not penetrate him or her. A person’s sense of self is determined by his or her proximity yet

distance from others. According to Imogen Tyler, “when the subject/object boundary is

breached, the object is transformed into an abject object” (77). Tyler goes on to say that the

abject is most apparent in “things in or through which the skin border has disintegrated or been

punctured in some way so as to expose the subject to the limits of self” (77). Abjection therefore

occurs at the breaking of skin; the breaking of this boundary between self and Other.

The vampire, more specifically the vampire bite, is the quintessential abject act. The

horrific nature of this act is depicted in scenes such as vampire Eric Northman ripping out the

throat of one of his captives in Season 2. Breaking down this image to the level of skin, the skin

of the captive is broken by Eric’s fangs. The boundary between self (the captive) and Other

(Eric) is breached. A piece of Eric (his fangs) is inside the skin of his captive and his captive’s

blood is inside Eric’s mouth (“Nothing But The Blood”). The boundaries of the two are blurred

in this moment. Shannon Winnubst elaborates on this idea. She states, “The vampire is a

bloodsucker. He sucks blood, transferring an illegitimate and disavowed substance, transforming

his ‘victims’ from the living to the undead, giving birth without sex, trafficking in the strange

and unruly logics of fluids, mixing and spilling and infecting blood” (8).

While the image of Eric Northman and his captive is one just of feeding and killing,

True Blood also incorporates the abject image of a vampire ‘giving birth’ to another vampire. In

Season 1, vampire Bill Compton breaks the skin of Jessica, a young girl, not to feed on her but to

‘give birth’ to her as a vampire (“To Love Is To Bury”). Here the subject/object boundaries are

Chorney 4

not just blurred through the breaking of skin, but the subject is actually changed by the object,

and a bond is created between the two. In True Blood jargon, this makes Bill Jessica’s “maker”

(“To Love Is To Bury”). Stephen Moyer, the actor who plays Bill Compton, acknowledges the

breaking of skin in the show. He is quoted saying, “Vampires create a hole in the neck where

there wasn’t one before. It’s the de-virginization – breaking the hymen, creating blood and then

drinking the vaginal blood. And there’s something sharp, the fang, which is probing and

penetrating and moving into it. So that’s pretty sexy. I think that makes vampires attractive”

(qtd. in Grigoriadis). Moyer’s quote alludes to the ‘sexy’ or erotic appeal of this abject image.

So while the vampire may be the quintessential abject image, the reaction to it is more than just

horror and fascination.

The breaking of skin in True Blood is not just about feeding, killing, or creating new

vampires. True Blood is referred to as sexy because sex is an essential part of the show. Sex

between vampires and humans on True Blood is often accompanied by the vampire biting the

human. Here the breaking of skin is an intimate act. This is best depicted in Season 1 when

Sookie, the lead character of the show, loses her virginity to Bill Compton. During this sex

scene, viewers of the show watch as Bill breaks both the skin and the hymen of his lover and the

boundaries of the two are completely blurred in the mixing of blood and fluids (“Cold Ground”).

While the logistics of breaking skin are the same as the other two scenes I have described, here

the eroticism of the act is highlighted. What should be an abject image is also erotic and

intimate. The vampire as an erotic image is not a far-fetched idea and historically the vampire

Chorney 5

has been eroticized such as the characterization of Dracula. The erotic body is described in an

article by Penelope Deutscher as “existing outside of its imagined limits rather than as enclosed,

as open towards otherness, or permeable, penetrable, vulnerable” (qtd. in Deutscher 151). The

mixing of the erotic and the abject therefore makes sense in that the erotic body is one which is

permeable, penetrable and open towards otherness and the abject object is one which penetrates.

The depiction of a vampire breaking the skin of a human is therefore both abject and erotic.

True Blood capitalizes on the appeal of these abject and erotic images. The fans of the

show must not be forgotten when discussing affective responses (such as abjection and desire).

True Blood fans love the vampires and they love the idea of the vampire bite. As stated in an

interview with Anna Paquin, the actress who plays Sookie, “True Blood clearly taps into the

current vogue for vampires started by the hit film Twilight. […] Its popular appeal is partly that

vampires have a ‘dark, dangerous, brooding sexuality” (Paquin). This point is made even more

apparent by Alexander Skarsgard (the actor who plays Eric Northman), who claims that fans

actually ask him to bite them. He comments, “That’s the one thing I’ll never really understand.

But the main reason I don’t ever do it is because if I do it just once, every single person will be

like ‘Bite me! Bite me! Bite me!’” (qtd. in Haramis).

Looking at these abject and erotic images in True Blood that are so appealing to fans,

such as Bill or Eric biting Sookie, how might these images be interpreted from a third wave

feminist standpoint? More specifically, are female characters being victimized in the show?

Depicting violent sex where the skin of the woman is broken as the (male) vampire bites into her

Chorney 6

neck could be construed as a derogatory image. Following particular strains of second wave

feminism most notable in the 1960s and 1970s, an image of the vulnerable female at the hands of

the powerful male could be read as oppressive to women. Rene Denfield has identified (and

criticized) second wave feminism as “pursuing an agenda based on unswerving belief in female

victimization at the hands of an all-powerful patriarchal system” (qtd. In Gamble, 47). This is

elaborated by Sue Thornham who argues, about mainstream North American cinema, that

“women […] are oppressed within the film industry […]; they are oppressed to being packaged

as images (sex objects, victims, or vampires)” (Thornham, 93). So this begs the question: is

Sookie a victim? My answer to this is no.

The breaking of skin is not so much about the vampire but about the person (woman)

whose skin is being broken. True Blood, it could be argued, is about sexual liberation. I follow

the ideas of many third wave feminist writers who have differed from and often criticized certain

extremist second wave feminists around, as Sarah Gamble explains, “issues of victimization,

autonomy and responsibility” (Gamble, 44). While I do not agree with all criticisms endorsed by

third wave feminists, I too am, as Gamble outlines, “critical of any definition of women as

victims who are unable to control their own lives” (44) and I, too, am also “unable to condemn

pornography” (Gamble 44). Pornographic images are taken up by some feminists as being

damaging to women. Catherine MacKinnon declares that “[t]his definition [of pornography as

the subordination of women] is coterminous with the industry, from Playboy […]through the

torture of women […] to snuff films, in which actual murder is the ultimate sexual act” (qtd. in

Chorney 7

Soble 171). True Blood’s use of sex counters the ideas presented by MacKinnon and is more in

tune with third wave feminist sentiments. When Sookie loses her virginity to Bill, she is

represented as choosing to do so. And she allows him to bite her (“Cold Ground”). When her

bite marks are discovered by her human friends, she defends her choice even though it is an

unpopular one (“Burning House of Love”). Throughout the show, Sookie continues to grow and

assert her ability to choose to engage or not engage in these activities. For example, in Season 3,

she chooses not to engage and bans both vampires (Bill and Eric) from her life (“Evil is Going

On”). Sookie uses a language of choice and does not let vampires dictate her decisions, sexually

or otherwise. This is best exemplified in Season 4 when Eric and Bill try to make the decision

for her not to participate in a fight against the witches that are endangering the vampires and

Sookie declares that it is her choice to put herself in danger. She says “And now maybe you can

both look at me and allow me to speak for myself. I can help” (“Spellbound”).

This language of choice is then taken a step further in the following episode when Sookie

has a very sexually liberating dream, reminiscent of the Rolling Stone cover, in which she

claims that she wants both Bill and Eric together. She declares:

First of all, you guys are vampires, what’s with all the morality? Second of all,

this is such a double standard, when it’s two women and one guy everyone’s

hunky dory with it even if they barely know each other, but when a woman tries

to have her way with two men that she is totally in love with everyone is hemmin’

and hawin’. I’m saying I love you, both of you, and I’m asking you to love me

Chorney 8

back, together. It’s either both of you or nothing at all, take it or leave it. (“Let’s

Get Out of Here”)

Moyer agrees that vampires are a method of sexual liberation for Sookie (qtd. in Grigoriadis).

He goes on to say that “It’s about taking things to the point where normal frames of society

wouldn’t think that was an OK thing for a young Southern girl to do” (qtd. in Grigoriadis). In

another interview, Moyer comments that “it’s about Sookie growing up and making decisions for

herself, rather than being the innocent that she began as. She starts as the innocent virgin, in the

first season, and she’s changed from there. She’s starting to choose what she wants” (Paquin and

Moyer). True Blood acknowledges the sexual liberation of women instead of deploring the

erotic images of them. According to Lynne Segal, new waves of feminists such as postfeminists

and third wave feminists “fear that we risk terminating women’s evolving exploration of our

sexuality and pleasure by forming alliances with, instead of strongly combating, the conservative

anti-pornography crusade” (8).

By making the abject images of vampires and the breaking of skin erotic, True Blood

represents the sexually empowered woman. True Blood shows that it is alright for women to be

sexually liberated, to do something beyond the norm, if that is their choice. Allan Soble argues

that “pornography provides an answer [to what men want] […]: women bound, women battered,

women tortured, women humiliated, women degraded and defiled, women killed” (17). True

Blood depicts this kind of violent sexuality but uses a juxtaposition of choice versus force to

distinguish between what is sexually liberating and what is not. The character of Sookie and her

Chorney 9

language of choice as I have discussed are juxtaposed with the character of Tara in Season 3. In

Season 3, Tara meets a vampire named Franklin and engages in consensual sex with him

(“Beautifully Bound”). Franklin then becomes obsessed with Tara and kidnaps her and

continually rapes and feeds on her (“I Got A Right To Sing The Blues”). In both cases (Sookie

and Tara), the audience is presented with scenes of sex and the biting of a human by a vampire.

The breaking of the skin of Sookie and the breaking of the skin of Tara in these two cases are

represented as very different; that difference being the ability to choose to engage in the act.

This juxtaposition, however, is complicated by racial connotations. Sookie is represented

as a white privileged female and she is juxtaposed with Tara, who is represented as a black,

disenfranchised female dealing with an alcoholic mother. This begs the question, as to who has

the privilege of choice? Sarah Gamble criticizes the assumption that “power is there for the

taking” (Gamble 49). She concludes that “If one is white, middle-class, educated and solvent

American, perhaps; but what if you are black, or poor […]? True Blood, too, shows in this

representation that choice is not ‘there for the taking’ and specific demographics may not have

or, possibly have to work harder for, this privilege.

True Blood also acknowledges that often there is opposition to a woman choosing to

engage in sexually liberating acts, and even goes so far as to villainize this opposition. The

villain of the first season is not the abject vampire or the sexually liberated woman who engages

with him, but a murderer who is killing what the show calls ‘fangbangers,’ women who choose

to have sex with vampires (“You’ll Be The Death of Me”). The villain specifically focuses on

Chorney 10

women who engage with male vampires but True Blood uses a multitude of human /vampire

pairings to show that the human female/vampire male pairing is not exclusive. True Blood uses

a blurring of female vampires biting both males and females, and male vampires biting both

males and females to reinforce that these images are not about the powerful male preying on the

vulnerable female.

True Blood not only blurs the boundaries of self and Other, abject and erotic but also the

boundaries of what is sexually ‘normal.’ Through the character of Sookie, a language of choice

is developed in which ‘acceptable sexuality’ is dictated by the individual not the society. The

breaking of skin in True Blood signifies both the biter and the individual being bitten and for the

individual choosing to be bitten, it can be a conscious mark of sexual liberation.

Chorney 11

Works Cited

Ball, Alan. “Interview: Alan Ball Talks ‘True Blood’, Vampire Sex, and Sookie’s HipHop Cred.” Complex 23 June 2011. Web. 29 Oct. 2011.

“Beautifully Bound.” True Blood. HBO. 20 June 2010. Television.

“Burning House of Love.” True Blood. HBO. 19 Oct. 2008. Television.

“Cold Ground.” True Blood. HBO. 12 Oct. 2008. Television.

Deutscher, Penelope. “Three touches to the skin and one look: Sartre and Beauvoir on

desire and embodiment.” Thinking Through the Skin. Ed. Ahmed, Sara, and Jackie

Stacey. New York: Routledge, 2001. 143-159. Print.

“Evil Is Going On.” True Blood. HBO. 12 July 2010. Television.

Gamble, Sarah. “Postfeminism.” The Routledge Companion to Feminism and Postfeminism.

Ed. Gamble, Sarah. London: Routledge, 2004. 29-42. Print.

Grigoriadis, Vanessa. “The Joy of Vampire Sex: The Schlocky, Sensual Secrets Behind

the Success of ‘True Blood.’” Rollingstone.com 2 Sept. 2010. Web. 29 Oct. 2011.

Haramis, Nick. “First a Vampire, Now a Leading Man: Alexander Skarsgard can’t be

tamed.” Blackbook 15 Sept. 2011. Web. 29 Oct. 2011.

“I Got A Right To Sing The Blues.” True Blood. HBO. 25 July 2011. Television.

“I Wish I Was The Moon.” True Blood. HBO. 31 July 2011. Television.

“Let’s Get Out Of Here.” True Blood. HBO. 21 Aug. 2011. Television.

“Nothing But The Blood.” True Blood. HBO. 14 June 2009. Television.

Paquin, Anna. “Anna Paquin: Interview for ‘True Blood’.” The Telegraph 5 Oct. 2009.

Web. 29 Oct. 2011.

Paquin, Anna, and Stephen Moyer. “Anna Paquin and Stephen Moyer Interview TRUE

Chorney 12

BLOOD Season 4.” collider.com 1 Aug. 2011. Web. 29 Oct. 2011.

Segal, Lynne. “Does Pornography Cause Violence? The Search for Evidence.” Dirty Looks:

Women, Pornography, Power. Ed. Church Gibson, Pamela, and Roma Gibson. London:

BFI Publishing, 1993. 1-4. Print.

Soble, Allan. Pornography, Sex and Feminism. New York: Prometheus Books, 2002.

Print.

“Spellbound.” True Blood. HBO. 14 Aug. 2011. Television.

Thornham, Sue. “Feminism and Film.” The Routledge Companion to Feminism and

Postfeminism. Ed. Gamble, Sarah. London: Routledge, 2004. 80-92. Print.

“To Love Is To Bury.” True Blood. HBO. 16 Nov. 2008. Television.

“True Blood.” facebook.com Facebook, 2011. Web. 1 Dec. 2011.

Tyler, Imogen. “Skin-tight: celebrity, pregnancy and subjectivity.” Thinking Through the Skin.

Ed. Ahmed, Sara, and Jackie Stacey. New York: Routledge, 2001. 69-84. Print.

Winnubst, Shannon. “Vampires, Anxieties, and Dreams: Race and Sex in the

Contemporary United States.” Hypatia 18.3 (Summer 2003): 1-20. Project

Muse. Web. 29 Oct. 2011.

“You’ll Be The Death Of Me.” True Blood. HBO. 23 Nov. 2008. Television.

Image

Rolston, Matthew. True Blood: They’re Hot. They’re Sexy. They’re Undead. 2 Sept. 2010.

rollingstone.com Web. 1 Dec. 2011.