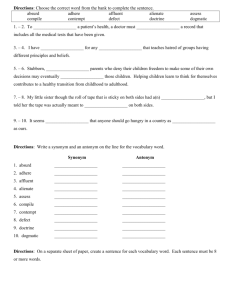

contempt of courts

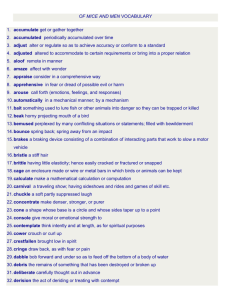

advertisement