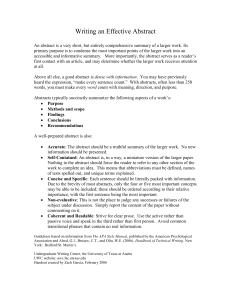

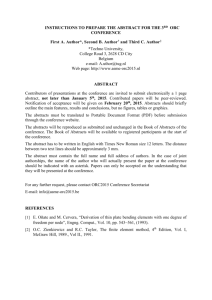

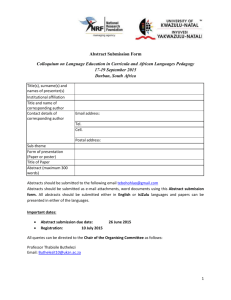

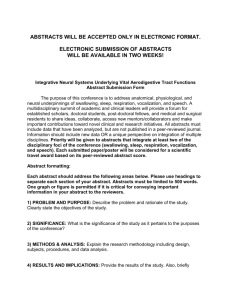

abstracts

advertisement