Ethical theories: religious ethics

advertisement

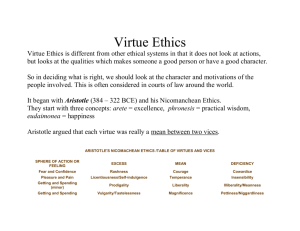

A2: Virtue Ethics A2 Ethics Virtue Ethics (Aristotle) 1 A2: Virtue Ethics 2 A2: Virtue Ethics Candidates should be able to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the ‘agent-centred’ nature of Virtue Ethics Agent-centred approach • Moral theories (Utilitarianism, Kantian Ethics) focus on the questions ‘What ought I do?’ ‘What is the right action?’ [act-centred approaches]. • Aristotle’s question: ‘What kind of a person ought I be?’ [agent-centred approach]. • Aristotle’s answer: ‘a good one.’ • Question – what is a good person? Aristotle’s Function Argument • Aristotle has a teleological metaphysics - things are categorised in terms of their unique function/purpose (telos). • In order to describe x as good, we need to: 1) know what sort of thing x is; and 2) know what the purpose of that kind of thing is. e.g. The unique purpose of an acorn is to grow into an oak tree. • An acorn is a potential oak tree, so … o A good acorn is one that does grow into an oak tree (its potential is realised by becoming an actual oak tree). o A bad acorn is one that fails to do so. • So in order to be able to say what a good person is, we need to know what the unique human purpose is. • Aristotle thought that all living things possess a nutritive soul, all animals possess a perceptive soul, and only humans possess a rational soul. • Since humans are the only creatures to be able to use reason (from the rational soul), our unique purpose/function is to reason well. • Humans that reason well are good humans. • "The function of man is activity of soul in accordance with reason.” 3 A2: Virtue Ethics Candidates should be able to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the concepts of eudaimonia and the Golden Mean Eudaimonia and human flourishing • When we reason well, we flourish. • This state of being (sometimes thought of as a kind of happiness or well-being) is called eudaimonia. • Eudaimonia is: o the highest human good o desired for its own sake (it is intrinsically good) o not a kind of bodily pleasure • But how do we reach eudaimonia? • Aristotle: By being virtuous. The virtues • Aristotle divided the virtues into two kinds: o Intellectual virtues (knowledge etc) - these can be learned from a teacher. o Moral virtues - these are practical virtues (they help you become a good person) - these are acquired through practice. • Aristotle posited 12 moral virtues (in your table, the 12 become 10 - Aristotle had two kinds of Generosity and two kinds of Pride). • In any area of human character, there will be two extremes – these are vices to be avoided. e.g., Fighting in a war. • Aristotle says the virtue (courage in this case) is somewhere in between these two vices. • When we behave virtuously, we can be said to have reached the Golden Mean • This principle is called the Doctrine of the Mean. 4 A2: Virtue Ethics Aristotle’s Vices and Virtues (simplified table) DOMAIN EXCESS MEAN DEFICIENCY Fear and Confidence Rashness/Foolhardiness Courage Cowardice Pleasure and Pain Self-indulgence Temperance Insensibility Getting and Spending Prodigality/Extravagence Generosity Stinginess/Meanness Honour and Dishonour Vanity Pride Undue humility Anger Irascibility Patience/Good temper Lack of spirit/Apathy Self-expression Boastfulness Truthfulness Understatement/mock modesty/Selfdeprecation Conversation Buffoonery Wittiness Boorishness Friendliness Unpleasantness Social Conduct Obsequiousness/Flattery Shame Shyness/Bashfulness Modesty Shamelessness Indignation Envy Righteous indignation Malicious enjoyment/Spitefulness 5 A2: Virtue Ethics Candidates should be able to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the importance of practising the virtues and the example of virtuous people; Being virtuous • Being a good person = being a virtuous person. • A virtuous person = someone for whom behaving virtuously is part of their second nature. • Our first nature is passive and unreflective. • Possessing a virtue is having a disposition to do certain things. Practising the virtues • We are not born virtuous - but we all do have the potential to become so. • Rosalind Hursthouse points out that although we hear about young mathematical prodigies, we do not hear of young virtuous prodigies. • We have to train to become virtuous - so that being virtuous is second nature. This takes time. • When we are virtuous, we behave virtuously out of habit - this is not a passive unthinking behaviour, but an active and rational way of being. The example of virtuous people • We can also become virtuous by aspiring to become like other virtuous people (archetypes) - e.g., Gandhi, Jesus etc. 6 A2: Virtue Ethics Candidates should be able to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of more modern approaches to Virtue Ethics G.E.M. Anscombe • Wrote ‘Modern Moral Philosophy’ (1958) • Moral theories that involve ‘you ought to …’ require God to give laws and enforce them. • Kantian Ethics & Utilitarianism lack the requisite foundation. • Virtue Ethics avoids this difficulty. Rosalind Hursthouse • Although we hear about young mathematical prodigies, we do not hear of young virtuous prodigies. • Being virtuous helps us in our moral deliberations – virtuous people more often make the ‘right’ decision. Philippa Foot • Goodness is relative to the kind of thing in question. • Humans are social animals, so good people live together well with others. • As Aristotle wrote: ‘Good is the same for the individual and the state.’ Keenan • Keenan thinks there are three important questions in Ethics: o Who am I? o Who ought I to become? o How do I get there? • He thinks Virtue Ethics has the tools to answer these questions. Alasdair MacIntyre • Wrote After Virtue (1981) • MacIntyre describes Moral Philosophy as being stuck in the Dark Ages since Virtue Ethics had been forgotten during the Enlightenment. • Promotes an agent-centred approach • Uses Ancient Greek ‘Heroic Society’ as an exemplar of how people work for the good of society. (Virtues of courage and fidelity to the fore). 7 A2: Virtue Ethics Candidates should be able to discuss these areas critically and their strengths and weaknesses Strengths 1. No need for a God to create moral laws. 2. Compatible with religious ethics 3. Ethics should be about becoming a good person. 4. Avoids the problem of morality simply being a case of ‘follow the rules!’. 5. Society will benefit if we are all good people. Weaknesses 1. Modern Science rejects the teleological classification of Nature. 2. The virtues are hard to pin down – ‘between two vices’ isn’t enough. 3. Are there not some virtues for which there cannot be a ‘too much’? 4. Schaller thinks moral rules come first, and virtues second: ‘Are virtues no more than dispositions to obey moral rules?’ So virtue ethics cannot be the whole story. 5. If we want Ethics to be action-guiding, virtue ethics doesn’t help as it is not actcentered. E.g., a moral dilemma, or an applied/practical ethics topic. 6. Robert Louden: we are correct to describe some acts as wrong – e.g., torturing innocents. 7. William Frankena: ‘Virtues without principles are blind.’ 8. Susan Wolf: Moral saints are boring – they lack the ability to enjoy life. Role models should be exciting! 8